The Best Movies of 2021

It was a year of octogenarian high jinks, long yet revealing documentaries, and masters reasserting themselvesLast year, I wrote about how hard it was to get two movie lovers to agree on a mutual top 10. This year, in the spirit of The Last Duel, Sean Fennessey and I decided to put our lists head-to-head—yet we still didn’t find room for the best Ridley Scott movie of the year, which will only make Sir Ridley crankier. The upshot of this exercise wasn’t just to spotlight as many worthy movies as possible, but to contrast different ideas about what constitutes cinematic value beyond taste. Even when there were instances of crossover in our lists, we seemed to be coming at the films themselves from different angles.

In terms of the bigger picture, moviegoing—and with it, processes of evaluation and canonization—may be getting back to something more like normal, and yet larger questions about the industry’s overall health and how films will (or won’t) reach audiences remain urgent and unanswered. In a moment when a company like Netflix can claim that Red Notice amassed 328 million hours of total viewership without producing a single receipt, it’s hard to feel certain about anything—except the fact that Red Notice isn’t on either of our lists. —Adam Nayman

10. Saint Maud

Directed by Rose Glass (A24)

Nayman: Back in April, I wondered whether anything would clear the bar set by Rose Glass’s uncannily well-executed debut. And unless you count the 40th anniversary rerelease and restoration of Andrzej Zulawski’s magnificently messed-up and terrifying Possession, no other horror movie came close. (However, let’s give a silver medal to James Wan’s Malignant for proving that the right way to spend all that Aquaman collateral was on a movie about a sentient tumor.) In a moment when critics and fans are caught up in debating the phenomenon and cinematic vocabulary of “elevated horror,” Saint Maud passed the audition as handcrafted, high-minded festival fare with Big Themes that didn’t sacrifice scares. It’s a beautifully made movie, as finely embroidered and darkly enveloping as a funeral shroud, and it’s carried by a heroic lead performance by Morfydd Clark as a woman whose belief that she can talk to God could be taken equally as delusions of grandeur or the pinnacle of humility. Glass knows how to ratchet tension, but also how to let scenes breathe. Topping it all off, Saint Maud sticks the landing with an ending that basically burns a hole through the screen. Ideally, horror movies show us things we can’t unsee; Glass’s money shot has been living rent-free in my mind’s eye for months now.

10. The Lost Daughter/C’mon C’mon

Directed by Maggie Gyllenhaal (Netflix)/Mike Mills (A24)

Sean Fennessey: Adam, I had a kid this year—our first—and it’s poisoned my movie brain. Where once I could a watch an endangered child on-screen and hardly bat an eyelash at the fictional terror, now I recoil at even the suggestion of a little girl or boy in peril. I’m a cliché dad, prudish and fragile, and that’s OK with me (for now). But what I had not anticipated is how this can work in other directions. In Maggie Gyllenhaal’s often unsettling adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s novel, she crafts a portrait of mothers at the end of their wits that is perceptive and relatable and fearless. It’s a movie that withholds judgment, but shows women constantly confronting the joy, toll, and simmering frustration of motherhood. Gyllenhaal is a first-time writer-director and hers is the most assured debut of the year, anchored by four terrific performers (Olivia Colman, Jessie Buckley, Dakota Johnson, and Dagmara Domińczyk) tasked with four visions of motherhood—one in repose, one in retreat, one in recalcitrance, and one in anticipation. I’m pairing it with C’mon C’mon, another of Mike Mills’s gentle and episodic works of miniature opera. After tackling his father (2011’s Beginners) and his mother (2017’s 20th Century Women), Mills is focusing on his child and his relationship to parenting. He uses a proxy uncle character, played with the record-flip softness that Joaquin Phoenix likes to break out after every Joker or so, to animate the parental love for a young boy ping-ponging between precocity and arrested development. Shot in gorgeously creamy black and white across L.A., New York, and New Orleans, it’s a movie not without scares or drama, but ultimately warm and refreshingly free of guile. It made me feel as good about this stage of my life as anything that isn’t my daughter.

9. The Power of the Dog

Directed by Jane Campion (Netflix)

Nayman: I also had a kid this year—bringing our household’s grand total to two–which didn’t so much poison my movie brain (can’t poison something that’s already toxic) but cut into my movie-viewing time so significantly that I’ve missed enough key 2021 titles to make me wonder about making a list in the first place. For instance: I haven’t seen The Lost Daughter, C’mon C’mon, The Tragedy of Macbeth, or Ghostbusters: Afterlife. How can I properly assess the year in cinema without Ghostbusters: Afterlife? The other wrinkle to having two kids is that even when I have managed to catch up with For Your Consideration stuff, it’s largely been at home via DVDs and screening links, which is why I’m grateful that I actually saw The Power of the Dog in a movie theater, where the exquisite wide-screen compositions and stinging musical score could feel suitably overpowering. So yes, I’m adding my voice to the choral praise for Jane Campion’s latest, not least of all because I can’t remember watching a movie of this kind—big, intricate, and literary, with a cleanly diagrammed structure and heavily underlined themes (dial M for masculinity)—that wrong-footed my expectations so deftly. Some critics were annoyed that it takes the plot a long time to kick in, but that’s not just good scene-setting by Campion—it’s a way to show that for some of the characters, decisive action is a long time coming. I liked the way that what seems to be an emotional triangle between two brothers and a woman keeps revealing new vertices, and the last half hour is some of the greatest work yet from a filmmaker who plays havoc with expectations while honoring a larger and inexorable design.

9. Drive My Car

Directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi (Janus Films)

Fennessey: With two notable exceptions, I saw every film on my list in a theater—a privilege I appreciate and don’t take for granted. That includes Hamaguchi’s epic tale of quiet contemplation, a movie about a man constantly on the move—in his vintage red Saab 900—but rarely able to move forward. Based on a rather terse Haruki Murakami short story, Hamaguchi’s rendition involves a theater actor and director channeling loss through a complex staging of Uncle Vanya that blends languages and symbols to cross cultures in Hiroshima. This is an audacious three-hour movie that is by turns restrained and remote, until an explosive finale that shifts the emotional turmoil from Hidetoshi Nishijima’s theater director to his driver and companion, played with a coiled power by Tôko Miura. Hamaguchi’s movie is beyond deliberate—it’s a study in pace and unknowable truths. But its mystery propels it forward to a feeling of autonavigation, the sense that life keeps hurtling toward you even if you want to run from it. Better to have seen it without the distractions of a life at home and a second screen in reach. Instead, let it drive right over you.

8. Wife of a Spy

Directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa (Kino Lorber)

Nayman: It was a great year for Monsieur Hamaguchi, who also cowrote the no. 8 movie on my list—one directed by his old film-school instructor. The title of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Wife of a Spy is very “it is what it is,” but starting with its brilliant, bristling screenplay and expanding outward through its director’s dexterous use of setting and shadow to evoke cloaked wartime motives, the film is as complexly pleasurable as any prestige thriller of recent years. Statuesque Satoko (Yu Aoi) is an actress married to successful importer-exporter Yusaku (Issey Takahashi), whose movements between Japan and Manchuria have piqued the interest of Kobe’s local authorities; when a woman in Yusaku’s circle turns up dead, she gets suspicious too. The chess board that Kurosawa keeps returning to in a series of symbolic close-ups summarizes the move-counter-move machinations of the plot, but what Kurosawa and his collaborators are really up to is more of a meditation on roles and performance. The devastating revelation of what Yusaku is really keeping hidden—or, perhaps, trying to expose—puts a political frame around the action while calling back to the apocalyptic horrors of Kurosawa’s previous genre masterpieces; superfans like myself can enjoy the shout-outs to Cure and Charisma while those unfamiliar Kurosawa’s cinema will simply recognize the touch of an old master.

8. Red Rocket

Directed by Sean Baker (A24)

Fennessey: There’s an awkward two-step happening in the dance of film discourse, swaying left to blindly stan actors and filmmakers no matter their cultural output or depth, and then swaying back right to adjudicate the moral and political valences of art above intention, or its absence. Movies are denounced before release based on a plot synopsis or ferociously defended in the face of criticism. Into this free-for-all parachutes Red Rocket. What to make of it? A gimlet-eyed portrait of a suitcase pimp returning home to Texas City, Texas, after a couple of decades working as a porn star in L.A., Baker’s movie at first feels like a provocation. His star, Simon Rex, is an ex-MTV VJ, alum of the Scary Movie series, and a post-Eminem shock rapper. He has a rubbery face and a whirling dervish spirit, all limbs and teeth and weathered skin. His character, Mikey Saber, wields a hustle that is cheery and destructive. He grooms young women, sells drugs, deceives his wife, and brags about it all to his lone friend. He’s disgusting. And yet, charming. Some of that is Rex, who is pure go-go-go, and some of that is the way Baker situates the character in a decrepit world where survival feels more important than decency. Saber is puerile but funny and ruthlessly determined—his story feels like a soft projection of all the hucksters and groping assholes who’ve blown into our political and social lives these past five (50?) years.

But is Saber really a stand-in for Donald Trump? That feels too elementary, and doesn’t do justice to the psychologically layered construction of the character, who desperately tries to win the audience (any audience) over even as he burns the world around him. Baker sets the antic pacing and boundary-challenging vim of Italian comedy against a gorgeously elegiac vision of a dying American center. (In the film, a doughnut shop operates in the shadow of an oil refinery—I’m not sure there’s a better metaphor for this country.) And while Baker doesn’t judge his characters, even when they’re monstrous, he’s manifested a unique confrontation for audiences, and perhaps the dreaded discourse, too. What to do with a problem like Mikey Saber? Get a close look at him. Maybe even hear him out. Just don’t stan him.

7. Old

Directed by M. Night Shyamalan (Universal)

Nayman: “Just don’t stan him”—the eternal conundrum when it comes to M. Night Shyamalan, who arguably makes it easier on his haters than any major working American director even as he preaches blissfully to the choir. Back in July, I called Night’s mystery about, yes, a Beach That Makes You Old, “a big swing that makes contact”—a reference to the oh-shit revelation in Signs that the only thing standing between Earth and an alien takeover was Joaquin Phoenix and his trusty wonderbat. Twenty years later, Shyamalan has lived down his reputation as a twist-monger, and he’s regrouped by taking and matching the pulse of a zeitgeist that had seemed to pass him by. The Visit found a genuinely inventive way to use found footage post–Paranormal Activity; Split and Glass simultaneously satirized and cashed in on the superhero cinematic universe trend. Old, meanwhile, takes on such trenchant, contemporary issues as the surveillance state, predatory pharmaceutical companies, and top 40 rappers called “Mid-Sized Sedan.” The moment when Mr. Sedan (Aaron Pierre) was identified as such by an ardent teenage fan was also the moment when Old won my heart, and I’m not likely to give it back anytime soon. In a period when even interesting filmmakers seem content to simply produce content, Shyamalan seems committed to keeping it weird. Thanks for the laughs, Night, and maybe, you know, hit me back …. just to chat. Truly yours, your biggest fan, etc.

7. Bergman Island

Directed by Mia Hansen-Løve (IFC Films)

Fennessey: This was quite a good year for directorial autofiction. Joanna Hogg completed her memoiristic The Souvenir diptych with a righteous glee. Janicza Bravo’s Zola transposed the oh-shit virality of a stripper’s Twitter thread onto a larcenous fairy tale of cultural identity. David Lowery’s The Green Knight quested to the heart of his greatest fear only to discover a whole lot of cowardice, and some resolve, too. Wes Anderson even made a movie about a visionary curator wrangling all of his charges to create something bigger than all of them. Directors like to see themselves in their stories, in case you hadn’t heard (or asked M. Night Shyamalan). Nowhere was that more evident or vital than in the French filmmaker Mia Hansen-Løve’s Bergman Island. A skilled chronicler of millennial ennui and quiet longing, Hansen-Løve takes her story of a husband-wife pair of filmmakers (a perfectly cast Tim Roth and Vicky Krieps, finally rewarded with a worthy follow-up to Phantom Thread) to the Swedish island of Fårö, where Ingmar Bergman lived, worked, and died. In another director’s hands, this might amount to hoary homage. But this is a mash-up of movie-within-movie nesting doll symbolism, with Hansen-Løve creating an unofficial follow-up to her 2011 film Goodbye, First Love, and unraveling our expectations of conventional narrative in the process. When Mia Wasikowska and Anders Danielsen Lie arrive as exes reunited at a wedding more than halfway through the film, it transforms into something sensual but self-abnegating. You can almost hear Hansen-Løve asking herself, “Is this a good idea?” Few directors are willing to work out their feelings out loud, and Bergman Island is not a movie with thunderous conclusions. But it has something that few examples of autofiction can claim: humility.

6. Annette

Directed by Leos Carax (Amazon Studios)

Nayman: You left out one key guy in your inventory of visceral autofiction. Say bonjour to Leos Carax, whose chaotic, seriocomic rock opera Annette is, among other things, a self-portrait of the artist—by the final scene, the wan, pencil-mustachioed Adam Driver (this year’s Best Actor) has become the spitting image of his director. I can’t say I found Annette’s mix of amour fou, fatal melodrama, puppet theatre, and pop-cultural pastiche completely successful or convincing. But no movie this year had higher highs, beginning with the opening, full-company sing-along that winkingly begs the audience’s permission to let the festivities commence, and peaking during a final duet between Driver and the titular child star that somehow echoes both Robert Bresson and Pinocchio. Is Driver’s caustic Bill Hicks routine as the “Ape of God” tough to sit through? Yes. Do all those pounding, tinny Sparks songs grow tiring after a while? Sure. Does Annette come out the other side of its annoyances and score the kind of bold, emotional coup we expect from the greatest movie musicals? For me, it did.

6. The Velvet Underground/The Beatles: Get Back

Directed by Todd Haynes (Apple)/Directed by Peter Jackson (Disney)

Fennessey: Forgive the double-up, but I don’t know how I could refuse. Consider the archival music documentary in which hardly any archival footage of the subject exists. That was the challenge Haynes conquered in his Velvet Underground film, adopting the ecstatic visual style of an Andy Warhol picture and the spelunking delight of an academic deep in his thesis to render a story about one of the more iconic, if not chronicled, bands of the 20th century and the New York artistic underground swelling around it. His Velvet Underground movie is downright electrifying, like watching culture get born in a tiny circle of noise.

Jackson, by contrast, had nothing but tape. Reams and reams and reams of John, Paul, George, Ringo, and their traveling circus near the twilight of the Beatles’ lifespan, originally shot for Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s dour 1970 film Let It Be. Jackson and his editor Jabez Olssen whittled, but still ended up with an eight-hour megadoc divided into three parts. In the process, they’ve dispelled accepted wisdom about the band, deepened the context of their chemistry, and showed the act of creation in a way that maybe no documentary ever has. Calling Get Back “revelatory” is like calling Tom Brady a “veteran quarterback”—it’s accurate, but it really doesn’t speak to the magnitude. This series is routinely awe-inducing, showing moments of subtle psychology and hilarious idiosyncrasy in equal measure. Together, these two films signal a capstone on 1960s nostalgia—no two acts more clearly represent the alpha and omega of baby boomer pop culture; one is a mainstream lodestar eventually guided by outsider art instincts, the other an emblem of the counterculture that was quickly co-opted by successive generations into pure pop magic. How’s that song go? “I’ll be your mirror …”

5. The Inheritance

Directed by Ephraim Asili (Grasshopper Film)

Nayman: The same late-’60s spirit of Get Back and The Velvet Underground haunts Ephraim Asili’s ingenious collectivist comedy The Inheritance, whose characters are attempting to uphold revolutionary ideals in a modern context. “We are a shoeless home,” explains one of the inhabitants of The House of Ubuntu, a residence modelled after (and located nearby) the West Philadelphia MOVE commune that was made infamous in 1985 by a fatal and ulimately unpunished police bombing; the line is resonant in the sense that Asili’s characters are trying to follow in the footsteps of the past. Principled, intellectual, 20-something Julian (Eric Lockley) has inherited the house from his late grandmother, and filled it with friends, colleagues, and hangers-on committed to studying a treasure trove of artifacts that, taken together, comprise a syllabus of modern African-American artistry and activism: books, magazines, records, sculptures, murals, manifestos. Partially based on his own experiences in a Black Marxist collective and brimming with affectionately self-deprecating dialogue, Asili’s film serves doubly as a showcase for Julian’s hallowed texts and a sly, formally rigorous satire on the paradoxical compromises of group living—the way that even ideological solidarity can’t prevent people from getting on one another’s nerves.

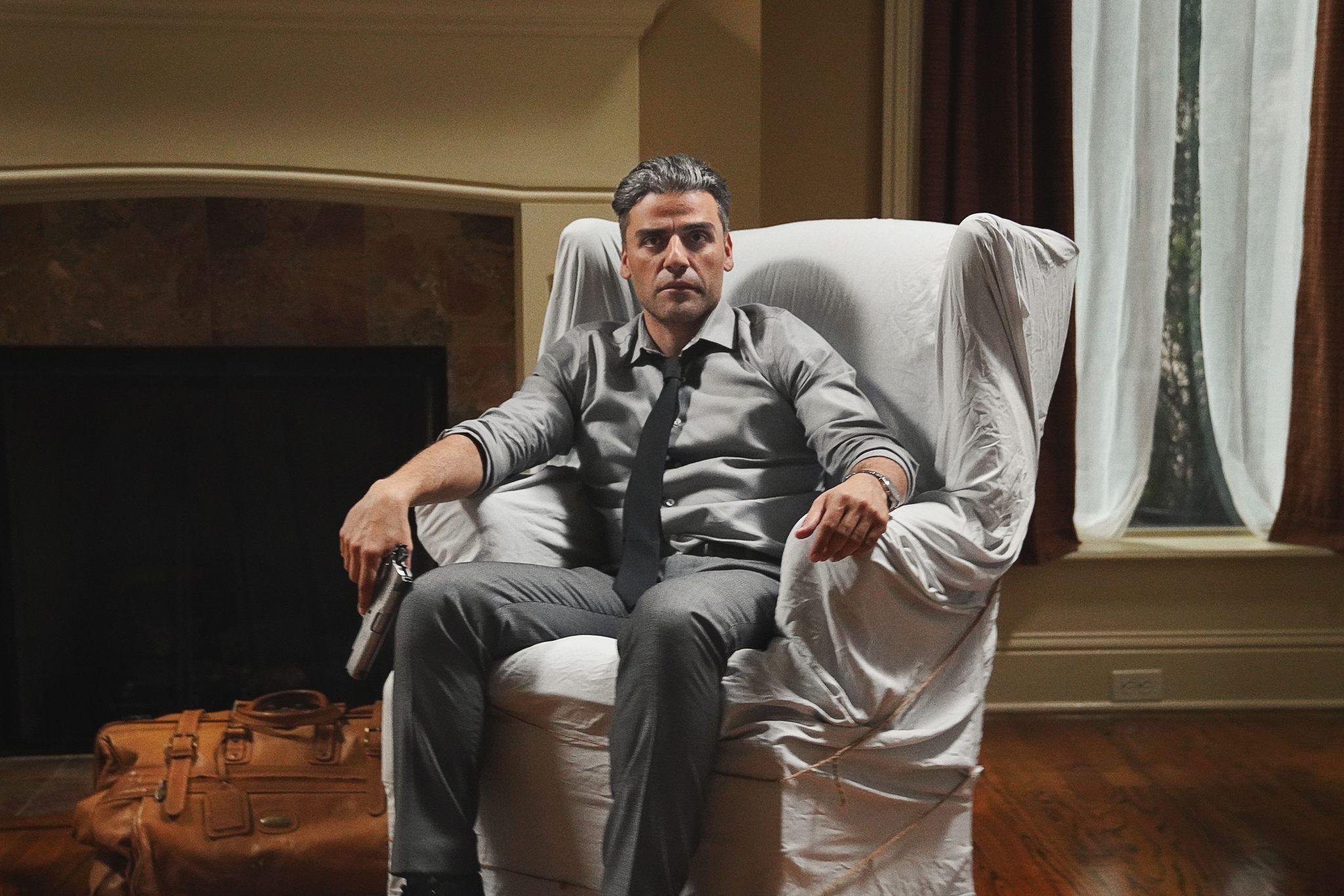

5. The Card Counter

Directed by Paul Schrader (Focus Features)

Fennessey: I made a pact with myself a long time ago that when Paul Schrader adds another wounded creature to his menagerie of God’s Lonely Men, I will abide with its inclusion on a year-end list. This is made a bit easier when the films assume the same sense of grace and despair as 2018’s First Reformed—this year’s entry, The Card Counter, does just that. His latest examination of alienation, soul death, and the American lie follows a one-time Abu Ghraib prison guard-torturer named William Tell (ha), haunted by his past and seeking to escape one full house at a time via the roadside casinos of these United States. Oscar Isaac, with his boxy good looks and hooded stare, is a Schrader monk par excellence. When he stumbles upon a young guy (Tye Sheridan, wormish) looking to avenge his father’s death, Tell is forced to face down his trauma. This is not a subtle film and not a terribly good gambling movie, but there is a psychic blankness in the performances—ascetic control trumping actorly vanity—that had me once again plumbing the depths of the torture cell Schrader calls his brain. I can count on one hand the number of filmmakers who are capable of ripping out the insulation of our daily lives and dragging it into view for everyone to wince at. Schrader is 75 years old, and his social media presence suggests a somewhat loony crank, but I hope he’s got a few more films in him. As our pals on The Press Box podcast like to joke, the old guy’s still got it!

4. Benedetta

Directed by Paul Verhoeven (IFC Films)

Nayman: Speaking of old guys who’ve still got it: Paul Verhoeven takes pole position amongst 2021’s octogenarian success stories. As much as I enjoyed both The Last Duel and Cry Macho, neither Ridley Scott nor Clint Eastwood can claim to be working from a position of industrial weakness. They’re playing with house money, while, like Schrader, Verhoeven has to try to game the system every time out. He’s currently in his third decade of professional exile from the U.S.A., and since refashioning himself as a classy, classical art-house filmmaker, he’s made a few of the best movies of his brilliantly checkered career. Five years ago, the viciously terrific thriller Elle sniffed the Oscar race. Now comes this deceptively sleazy, intellectually searching fact-based period piece about a nun experiencing mystic visions in 17th century Italy. What Do You Do With a Problem Like Benedetta? As played by the superlative Virginie Efira, Verhoeven’s heroine is a mystery wrapped in a riddle inside an enigma—she claims to have a direct line to God, and one of the fringe benefits of her successful power grab at the local abbey is that she gets a private room to hook up with her fellow sister Bartolomea. Having been taught from a young age to hate her body, suddenly, she’s loving it. Is she a faker? An opportunist? A rebel with a cause? Or does the Lord work in mysterious ways? Certainly, Verhoeven does, mixing lurid, cynical exploitation with fluid storytelling and the principled irreverence of a satirist whose art always punches up against institutional dogma and scores a knockout—hopefully not for the last time.

4. Can’t Get You Out of My Head

Directed by Adam Curtis (BBC)

Fennessey: If the Beatles felt so big that they could not be confined to anything less than 468 minutes, imagine how long a film that purports to untangle the hidden connections that link national myths, artificial intelligence, collectivist fallacies, imperialism, China’s Cultural Revolution, and 2Pac should be. At least 10 minutes longer, according to Adam Curtis, who has been creating overwhelming recombinant visions of our cursed past and paranoid future for the BBC for the better part of four decades. His latest is his biggest, widest, and chewiest—a tapestry of conspiracy theory, lawyerly evidentiary presentation, archival wizardry, and Curtis’s trademark needle drops. Blended together across nearly eight hours, Can’t Get You Out of My Head remains my definitive document of quarantine power-watching. (The film has not officially been released in the United States, though it can be seen on YouTube.) I subjected my then-pregnant wife to the experience over two typically isolated days this winter and while I can’t say this is the kind of uplifting material you’d like to view as you prepare to bring life into the world, I remain tantalized by Curtis’s style and mission. Are some of his conclusions big-brained leaps of logic? Perhaps, but you don’t have to be convinced of anything beyond Curtis’s utter commitment to his truth. In less skilled hands, you’d have, well, a bad YouTube documentary. And maybe this is merely the steroidal version of subgenre that has wrought havoc on the minds of millions over the past decade. But Curtis’s deeply researched, literate, and cosmic sense of events suggests a world not of individual moments but a star system, flashes of light that when connected create a constellation of existence.

3. Azor

Directed by Andreas Fontana (Mubi)

Nayman: The protagonist of Azor likes to give assurances: on assignment in Buenos Aires circa 1980 representing a high-end Swiss bank, Yvan (Fabrizio Rongione) tells his clients that their money is safe. But the country is edging towards economic and political chaos, and Yvan’s boss and colleague Mr. Keys is nowhere to be found in a moment where Argentina’s ruling powers are known for “disappearing” anybody inconvenient to the regime. The missing-person subplot gives Azor a thriller hook, but beyond the machinations of its plot, the film achieves a kind of ambient creepiness in which every encounter, no matter how refined or banal, seems to point to sinister intentions. The film’s dark-hued, painterly images evoke New Hollywood thrillers like Chinatown and Night Moves, and, as in those films, it’s as if reality were rotting from the inside out. It’s a fine line between subtlety and stasis, and Azor’s slow-burn may be challenging for viewers who crave more consistent stimulation. But if marinating in paranoia is your idea of a good time, Fontana’s beautifully executed debut is as good as it gets.

3. Dune

Directed by Denis Villeneuve (Warner Bros.)

Fennessey: Sometimes bigger is better, goddamnit! This was a lousy year for conventional blockbusters, and I typically like to find one or two a year that rises to the level of visceral joy that only a shiny, noisy Hollywood production can create. I’m not sure Dune is a joyful film—that isn’t quite Villeneuve’s register—but I was transported by his adaptation of Frank Herbert’s beloved, oft-adapted-but-never-nailed novel. The ambition and scope is invigorating. A longtime passion project, this is a movie where a filmmaker is attacking the source material head on with respect, admiration, and a visionary craftsmanship that perhaps even its author didn’t know was possible when he was writing. Herbert’s novel is a psychotronic tangle of heady imagery, and the film strips away the haze to focus on the arid desperation and religiosity of its characters without sacrificing the grandeur of sandworms, thopters, and the slug majesty of its villain Baron Harkonnen. Hollywood is going through a difficult transitional period with regard to big-budget movies—if it ain’t MCU/DCEU/Fast, it ain’t a sure thing. Unless—unless!—we entrust hundreds of millions of dollars to blindly driven auteurs adapting books they have loved since adolescence. Roger Ebert once wrote that movie theaters “unashamedly provided a proscenium for our dreams.” In Dune, Villeneuve dreams big and boldly. [Uses the voice] Go to sleep!

2. Licorice Pizza

Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson (MGM/United Artists)

Nayman: I’ve already written some thoughts on PTA’s freewheeling teen comedy. The only thing I want to add in this year-end context is that of all the top-tier auteurs who’ve released new work in 2021, Anderson seems to have been the most inspired by shooting under limited conditions. Part of what’s so beguiling about Licorice Pizza is how it seems to take place in a world where grown-ups aren’t really around—the San Fernando Valley circa 1973 becomes a playground for characters on the verge of maturity, whether growing up too quickly or not soon enough. The slightly uncanny quality of the location shooting can be chalked up to the director’s mandate to shoot closer to home (including some family cameos), but the vibes aren’t wholly cozy or nostalgic. Amidst all the hijinks, there’s a feeling of encroaching crisis, or maybe a bubble about to burst. Time keeps on slipping throughout Licorice Pizza, faster and faster, and Anderson and his ever-agile camera take it in stride. This is filmmaking that doesn’t break a sweat.

2. The Worst Person in the World

Directed by Joachim Trier (Neon)

Fennessey: I have clear and undistorted memories of critical decision-making points in my late 20s and early 30s. Take this job, move to this city, befriend this person, go to that party, maybe pack it in tonight, three whiskeys is enough, sir. I live a more domesticated life these days, often homebound and unambitious, but occasionally I will think back on some of those choices. Did I miss out on meeting someone at that party who could have changed it all for me? Or have I played the notes of life as well as possible? I definitely blew it on more than one occasion, but I’m happy and healthy and … well, this all sounds like rationalization doesn’t it? What you’re reading right now is solipsism and I’m far from above it. Most people born after 1980, at least, aren’t either. Joachim Trier understands this: In the final third of his Oslo Trilogy, the Norwegian director trains his eye on Julie, an intelligent, vivacious young woman who frequently seems to make the wrong choice. They’re not cataclysmic decisions, but anytime a relationship or a career path makes some headway in her psyche, she flees. Renate Reinsve plays Julie, in what I believe is the performance of the year, as a woman with a deeply Millennial sense of false bravado—she’s a person roiling with feelings and beliefs but harboring self-doubt and confusion at every turn. I recognize Julie. If I am not her, I have met her, worked with her, had Zoom calls with her while she blithely presented her grand vision of the world to me. It is the confidence and passion of a person who was told that she can be anything she wants colliding with the reality that maybe, just maybe, she can. Trier and co-writer Eskil Vogt have an uncanny feel for this conundrum, crafting the movie into 12 discrete parts, a self-consciously novelistic approach that does, in fact, reflect how people tend to recall their youth. This movie knocked me over. Everyone should see it.

1. Drive My Car/Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy

Directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi (Janus Films and Film Movement)

Nayman: Sean, you already very accurately described Drive My Car as a movie that cruises right over you. And I know it’s a bit cliché at this point to roll over for Ryusuke Hamaguchi, but the guy is just such a controlled, intelligent filmmaker, and he’s on a hot streak. Where Drive My Car chugs along with brilliant linearity—leaping across weeks and years to chronicle an artist’s struggle to turn grief into inspiration—Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy turns curlicues about chance, fate, and heartbreak. It’s made up of three miniature 40-minute dramas, each featuring sexy, existentially angsty characters; each with a delicious twist; each whirling away in succession, one after another, like a perfect little anthology of short stories. No movies this year took more pleasure in the architecture and engineering of narrative. And no matter how precarious and intricate the structures get, they hold up, with Drive My Car’s chassis reinforced by Chekhov and Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy dipping into speculative science-fiction in a finale that moved me more than anything else I saw all year.

1. Licorice Pizza

Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson (MGM/United Artists)

Fennessey: Anyone who has read or listened to me over the years knows that Paul Thomas Anderson is my favorite filmmaker. I’ll admit I sometimes struggle to put to words why I remain ensnared by his films. I think the word is “ineffable.” Of course he’s a master filmmaker—he’s seen it all and knows what he likes. But what do I like? Perhaps it’s the overweening sense of intensity meeting the sneeringly hilarious disposition of his characters. (“There are times when I look at people and I see nothing worth liking.”) Maybe it’s the absolute delight he takes in capturing his characters in motion. It’s possible we share a sense of humor, and his frequency is coming over the airwaves loud and clear to me. He makes movies that feel Important, but I think that’s a feint. What we want from artists is purely individualized expression—PTA makes movies only he can make. Licorice Pizza feels like a perfectly reconstructed memory, like someone hopped in a time machine and brought a 35mm camera. Which is not to say it’s a documentary—it has all the clever set-ups, brisk editing, and euphoric climaxes of great filmmaking, like Hal Ashby got lost in the Valley and pulled over for a bite. He gets remarkable performances from Cooper Hoffman and Alana Haim, two first-time actors representing the sensation of infatuation, if not consummation. He selects songs impeccably, as if touched by John Peel. He shoots L.A. like it’s Babylon, a place where people are born and eventually entombed in the glorious, dumb history of this company town. Licorice Pizza is a showbiz movie about all the reckless, dangerous ghouls who haunted the industry, and also a pie-eyed picture of kids just trying to make something of themselves. It’s hard to describe why I loved it. But I know that I did.