The Subversive Playfulness of the ‘The Matrix’

The Wachowski sisters tackle the most gigantic questions known to humanity—reality, identity, knowledge, causality, memory—with a spirit of play. They understand that while from one angle nothing matters more than these questions, from another angle they’re curiously insubstantial. They mean everything and nothing at all.

The funny thing about big metaphysical questions—I mean the real ground-floor Philosophy 101 stuff, the “what is reality” stuff, the “can we trust the evidence of our senses” stuff, the questions the Matrix film franchise has always loved to chew on—the funny thing about these questions is the way they manage to be utterly essential and absolutely superfluous at the same time.

Do we really exist? Who knows! You’d think a sentient species would put the Wednesday to-do list on hold until it got to the bottom of that quandary, but humanity tumbles along, buying socks and playing the xylophone, despite having made almost no discernible progress beyond “opinions vary.” It’s a good bit: Reality may not be real, but here we are, still doing laundry. I can’t prove I’m not a butterfly dreaming I’m Brian Phillips, but I still try to avoid parking tickets; the universe may be a delusion, but I feed my dogs every day. Life doesn’t care, for the most part, whether it’s on sound epistemological footing. This is one of the many funny things about life.

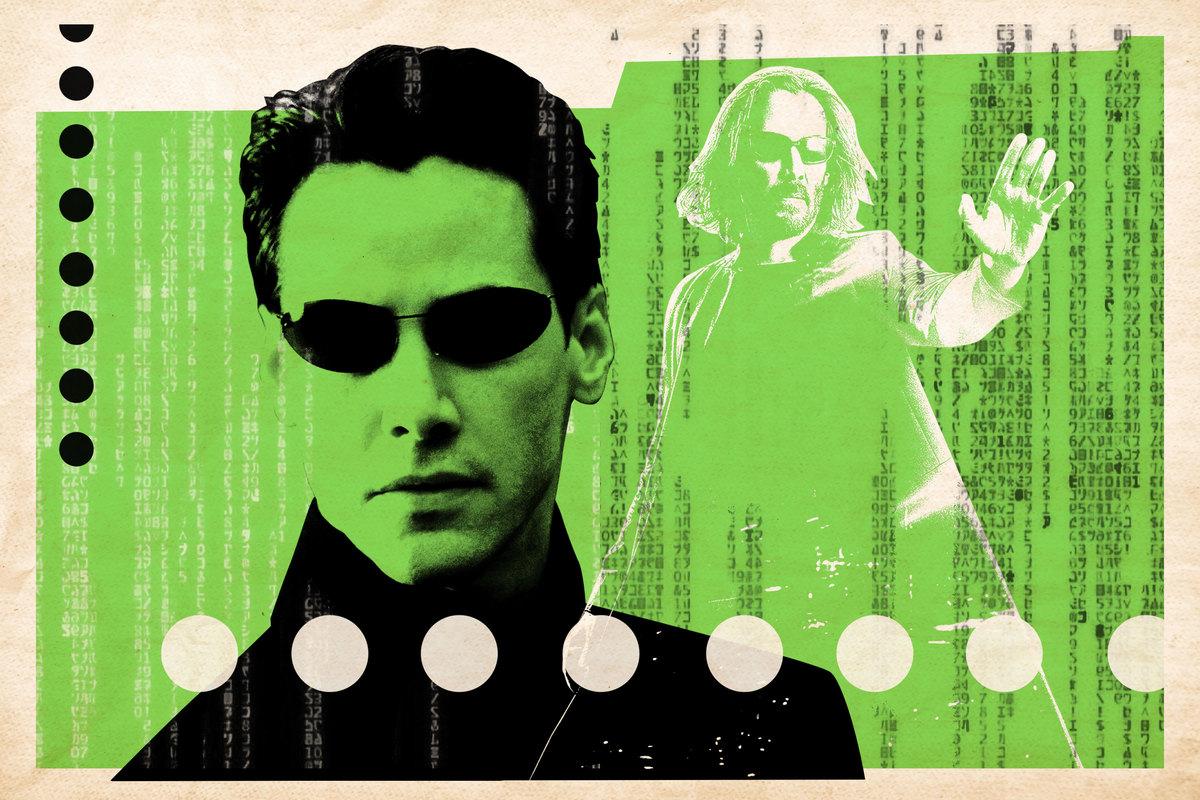

It’s also one of the funny things about the subset of life that is the Matrix franchise. I should say here: The Matrix movies are funny. I mean deliberately, knowingly funny. They’re not often talked about that way; they have a reputation for self-serious dorm-room philosophizing, and it’s, uh, not wholly unearned. But apart from the dour Matrix Revolutions, they’re also slyly and exuberantly comic. “Mr. Anderson”—that’s funny. The Lewis Carroll references are funny. The over-the-top ’80s-cyberpunk Neuromancer fits are a little funny, especially in a franchise that’s so determined to push its genres forward everywhere else. And the ways in which the films are funny are important—in some ways, they point toward the big themes of the films even more directly than the metaphysical exposition. The newest film, The Matrix Resurrections—which is both the first new franchise entry in 18 years and the first to be directed by Lana Wachowski without her sister Lilly—may be the funniest yet.

You’ve probably heard by now about the Alice-out-of-Wonderland opening act, featuring Keanu Reeves’s Neo as a melancholy game designer and Carrie-Anne Moss’s Trinity as a bored suburban mom. Maybe you’ve also heard about the movie’s ruthlessly self-referential mockery of the nostalgia industry from whose forehead it sprang. Resurrections uses overt satire to interrogate its own place in the Matrix canon and the significance of that canon itself, and if it isn’t the most brilliantly subversive latter-day sequel we’ve ever seen—Twin Peaks: The Return managed to upend the legacy of the original series while also immeasurably deepening it, something that doesn’t quite happen here—it’s still pretty thrilling. The Catrix? I laughed.

Under the overtly satirical arcs, though, there’s a more general atmosphere of subtle comedy, an atmosphere Resurrections shares with its predecessors. A half-hidden spark of knowing absurdism fizzes inside many of the franchise’s most grimly profound scenes. It has to do, I think, with the odd tension in all those big ideas. The Matrix is about the most gigantic questions known to humanity—reality, identity, knowledge, causality, memory—but it can afford to toy with them, rearrange them, change its mind about them, define them one way and then casually redefine them; it can afford to tackle them in a spirit of play. Because while from one angle nothing matters more than these questions, from another angle they’re curiously insubstantial. They mean everything and nothing at all.

The humor this situation makes possible is something very different from the humor you normally encounter in action movies. Compare The Matrix to Die Hard, for instance: a really funny movie, but one that locates all its comedy in its characters’ responses to the tough situation they’re in, while remaining essentially committed to the grim stakes of its premise. The Wachowskis favor more self-important characters—I love Morpheus, but to get a beer with, he seems about as chill a hang as your average Sith lord—and they’re more overt and script-bound in their handling of themes. But they also love to exaggerate and amplify the absurdities inherent in their stories, especially where those absurdities are cool and/or function as parodies of everyday, square, quotidian life. Here’s a man downloading kung-fu into his brain (cool, funny). Here’s a computer program reimagined as a Eurotrash sybarite (cool, parodic, funny). Here’s a computer security routine reimagined as a Magritte-like proliferation of somber men in black suits (funny, parodic, also weirdly beautiful?). Instead of a serious context populated by irreverent heroes, the Matrix gives us a surprisingly irreverent context populated by mostly serious heroes. I’m not sure which of these approaches is a more accurate perspective on what I’m going to go ahead and call the real world.

I don’t mean to say The Matrix is tongue-in-cheek or insincere. It’s more true to say that it’s free to be as heartfelt as it is because its sense of play allows it to go where it wants to go without worrying too much about contradictions. It’s not a set of fully realized ideas frozen into one solemn overarching allegory. It’s an array of ideas-in-progress (about capitalism, technology, gender, media, politics) that happen to share time in the same symbols and the same narrative frame. The effect is of filmmakers bringing the audience along as they think through a worldview in real time, via the unlikely medium of blockbuster action cinema. Which explains many of the very noticeable differences between the Matrix movies and others in their budget tier. Compared to, say, a Marvel film, the Matrix franchise is less predictable, more awkward; less determined to please its audience, more determined to respect it; less likely to use self-referentiality for fan service, more likely to use self-referentiality for self-critique; less commercial in its conception, more searching and lyrical (while still being steeped in commerce, mostly because the world-building of the first film remains so astonishingly charismatic).

This is a strange set of characteristics for a big-budget action series to possess, and Lana Wachowski is fully aware of it. There’s a funny scene in Resurrections in which a group of video-game writers sits around a table discussing what makes The Matrix, which is a game in the world of Resurrections, itself: Is it the heady philosophical content? The groundbreaking action sequences? Bullet time? The franchise’s giddy multiplicity means it sometimes gets in its own way—cf. the co-opting of the red pill–blue pill imagery from the first film by essentially the last people on earth the Wachowskis intended it for. But it also gives the Matrix a generosity, a warmth, that’s rare in an IP-based corporate entertainment product. Especially an IP-based corporate entertainment product that’s this devoted to black leather and sunglasses.

There’s this one sequence in the middle of Resurrections. Not really an important bit of the film, but it hit me while I was watching it that this quality of warmth is the thing I treasure most about the Wachowskis’ movies—and I do treasure them, even when I don’t think they “work” in the professional, conventional way that, say, most Marvel movies or most Pixar movies work. Here’s the sequence. Neo has escaped the Matrix yet again. He’s trying to figure out how to get back in to save Trinity. In the meantime, he’s been taken by the usual scrappy crew of hackers and mechanics to the human city of Io, the successor of Zion from the first film. Jada Pinkett Smith, who’s back as Niobe and distractingly made up to look like an octogenarian, takes him to visit a lab where a garden engineer and a sentient AI are trying, collaboratively, to reverse-engineer a strawberry. The first thing I thought, watching this, was come on, there is no reason for this strawberry to eat screen time in a 148-minute movie. The second thing I thought was I bet Lana Wachowski knows everything about this strawberry scientist and her relationship with this AI, and would be happy to spend the next two hours just watching them putter around in the lab. (Wachowski cowrote the screenplay with two talented novelists, David Mitchell and Aleksandar Hemon.) A couple of minutes later a bunch of people are standing around on a balcony when this startlingly beautiful silvery flying robot manta ray swoops up to the railing, out of nowhere. Niobe says something like, Hey, don’t worry about the flying silvery robot manta ray—it’s a friend.

That’s it; that’s the sequence. Strawberry, weird ghostly space-fish. (It’s a friend.) There’s a kind of casual wonder that you find in old pulp stories sometimes, stories where the technical perfection of the narrative matters less than the charm of the individual waypoints. I imagined something stunning, the writer says; here it is. Maybe it’s an image, maybe it’s a symbol, maybe it’s a handful of scenes. Not everything around it has to be equally polished. It’s just good that these things exist. It is good to see a sudden flying manta ray. It is good to know about the person whose job after the apocalypse is to reinvent the strawberry.

This quality of pulp generosity is present in all the Wachowskis’ best work. It’s why I love Jupiter Ascending, a film that certainly does not fit the criterion for artistic success in numerous conventional ways—but I love it, because it’s so inviting, so happy to be itself. It’s not giving you what some audience survey claimed to want, it’s giving you something the filmmakers themselves want and value. It’s why I have only fond feelings for Cloud Atlas, a movie I think is legitimately bad, but one that I’d choose to rewatch over any number of more conventionally successful films.

And by the same token, no matter how much CGI is present, you never feel that a studio algorithm could have made a Wachowski movie. The Matrix could not have made The Matrix. (It could maybe have made Iron Man 3.) Imperfect stitching can be a prized trait in hand-sewn garments, because the very deviations from perfection reveal the touch of a human maker. I feel something like that every time the second act of a Wachowski movie swerves into an eight-minute expository monologue during which a man in purple shades quotes Foucault on biopower or whatever. People made this because they wanted it to exist. How often at the movies these days do you feel like you’re spending time with people?

It’s good that these beautiful, imperfect things exist. In some ways this is the explicit ethos of the Matrix franchise, especially Matrix Resurrections, a film that meticulously seeks out and bridges the apparently exclusive dualities of the first three films. The machines are no longer exclusively evil; some of them now work to help humanity. The gender dynamic of the first three films, with Neo as the messianic figure of the One and Trinity as a sort of ass-kicking, leather-clad helpmeet, is now expanded and complicated; it turns out that Neo and Trinity are both chosen. They have access to their full power only when they’re together. The Two! (Yes, the ending is a little janky; hand stitching often is.) This has been read as a love-conquers-all message by critics. To me the point seemed less about romantic love and more about unifying apparently irreconcilable energies—humanity and technology, the masculine and the feminine—and discovering that they’re stronger together. The Wachowskis, of course, are both trans women, and have spoken publicly about the Matrix narrative as a metaphor for trans awakening. You’re trapped in a false reality, imposed on you from the outside; you have to find your way out.

That’s probably the loveliest—and considering who some of The Matrix’s fans are, also the funniest—of all the layers of meaning in the movies. The game Sad Neo is trying to design at the beginning of Resurrections is called Binary. That he can’t finish it is another good joke, and one that’s wholly in keeping with the spirit of this beautiful, imperfect franchise. Liberation, for the Matrix, isn’t a matter of fitting some preconceived criterion, whether of success, identity, or merit. It’s about being everything you are.