Scott Hall died this week at age 63, having suffered multiple heart attacks after developing a blood clot issue after hip replacement surgery. His death saddened wrestling fans who had followed him throughout his career, but it didn’t exactly come as a surprise—the hard-living “Attitude Era” pioneer had, by his own admission, cheated death multiple times during the previous four decades. Along the way, his considerable talents ensured that, in his own words, he kept “falling forward,” first as a can’t-miss rising star in the American Wrestling Association who looked like a cross between Hulk Hogan and Magnum T.A.; then as the Scarface-inspired Razor Ramon working among the WWF’s “New Generation” of post-Hulkamania stars; and finally as part of the “Outsiders” tag team with fellow WWF alum Kevin Nash, whose departure with Hall from WWF for the greener financial pastures of WCW inaugurated the late-1990s promotional wars that many consider the sport’s golden age.

As described by Hall in the 2011 ESPN E:60 documentary that probed the psychological depths of his later-career struggles with drug addiction and depression, he led an itinerant childhood, the son of a “big shot in the army” who was also a “hard-drinking redneck” like most of the men in the family. His father’s alcoholism led to Hall’s becoming “the head of the household at 15,” which, despite his size and athleticism, kept him out of organized sports as he switched from school to school, including Great Mills High School in Great Mills, Maryland, and another secondary institution in Munich, Germany. In a moment of sobriety, Hall’s father cautioned him that he would likely face similar addiction issues and should try to “fall forward” if and when that happened.

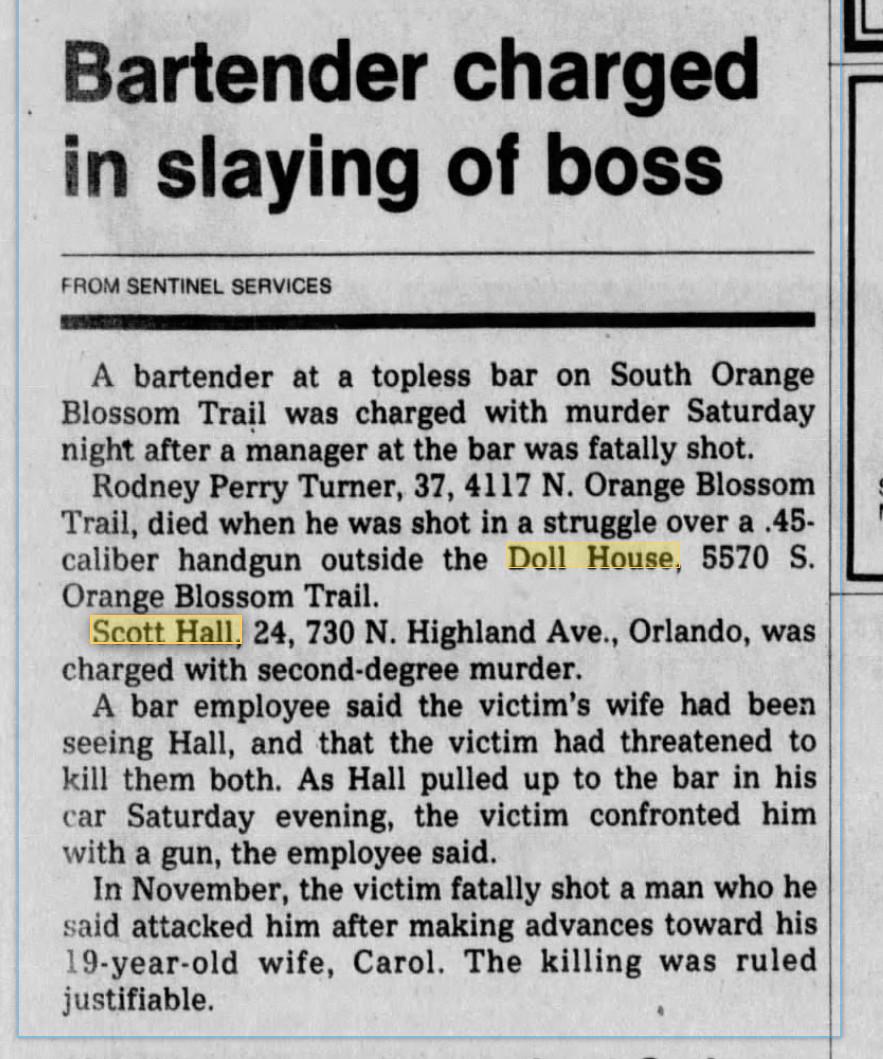

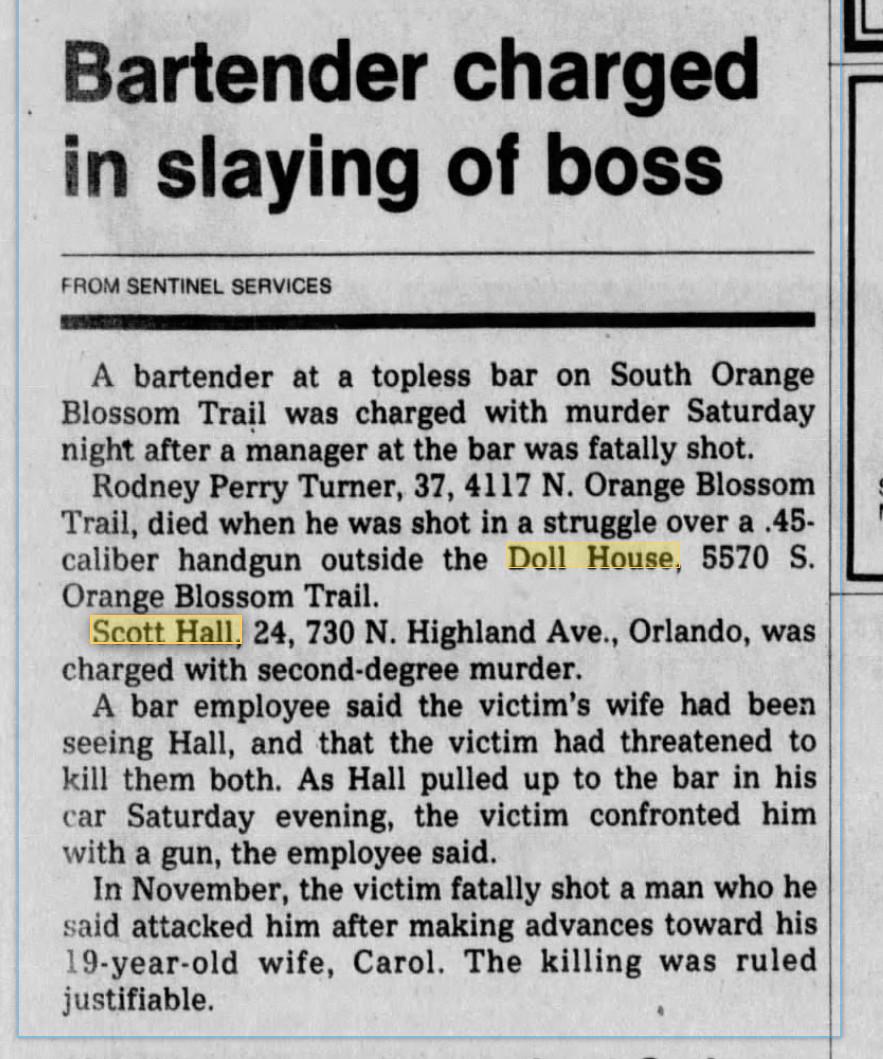

After high school, Hall made his way to Orlando, Florida, where he learned to lift weights and take steroids while tending bar at Thee Original Dollhouse, a popular area strip club that both then and now made the news for the dangerous encounters that sometimes occurred on the premises. It was there where Hall, on the night of January 15, 1983, was attacked by a man with a gun—a fight that Hall said on the E:60 documentary occurred “over a girl.” “As I closed the distance, I remember what he was wearing, what I was wearing, what it smelled like,” Hall recalled, before describing how “I drilled him, he went down, his shirt went up, and he was reaching for the [firearm], so I reached for it too. We wrestled around with it. I took it and shot him in the head. … A guy pulled a weapon on me, and I took it away and shot him, point-blank.”

What the documentary did not do—but what the Orlando Sentinel did at the time—was provide richer context for the vicious attack, which was determined to be an act of self-defense. In an article published on January 16, the Sentinel reported that the man who attacked Hall was Rodney Perry Turner, the 37-year-old manager of the bar whose 19-year-old wife Hall had allegedly been seeing on the side. Turner had a history with justifiable homicide, with a Sentinel article from December 14, 1982, describing an incident when he fought off two men, one of whom who had assaulted him and made unwanted advances toward his wife before killing one of them, another violent killing ruled justifiable.

Article about the Hall incident from the January 16, 1983, edition of the Orlando Sentinel.

In other words, Scott Hall—already huge and strong, brimming with self-confidence and an ability to handle himself—found himself facing a jealous husband who also happened to be his boss and who had killed another man roughly one month prior to attacking Hall. Although Hall survived, the trauma, to which Hall only alludes in his heartfelt E:60 interview, is apparent.

In his book On Killing, retired Army colonel Dave Grossman emphasizes that an act of killing that occurs when the person is psychologically unprepared for it or unable to justify it to themselves can cause tremendous long-term emotional harm. Hall’s own summation suggests how the event negatively impacted the rest of his life: “A guy was dead, and I’m the reason.” Bret Hart, who had good matches with Hall in the early 1990s but wasn’t particularly close to him, remarked on Facebook after Hall’s passing that “I think Scott carried many heavy crosses long before I ever knew him”—which is putting it mildly.

Still, Hall’s overwhelming size, impressive for any era, that ensured his future in wrestling would be bright. Like fellow Floridians Hulk Hogan and Paul Orndorff, Hall had trained with local wrestler Hiro Matsuda, then wound up a featured attraction in the Florida promotion after future NWA world heavyweight champion Barry Windham caught sight of the future “Bad Guy” in a supermarket and took him under his wing, giving Hall plenty of mat time with Windham’s tag team partner Mike Rotunda—not far removed from a stellar amateur wrestling career at Syracuse University—and helping push him into a brief program with Dusty Rhodes as well as a tag team with fellow promising big man Dan Spivey.

Marty Jannetty recalled that Hall and Spivey “looked great, but as soon as they started working, I thought, ‘OK.’ Of course, they both got better, a lot better,” in an interview about the Spivey-Hall pairing’s potential. “Scott was very green, a very big man. That was the biggest he was back then. He was close to 290. Later, he leaned out, and got to 275, 270. God, he just looked like a monster.”

Hall’s superior size, hair-sprayed mullet, and powerhouse frame landed him on veteran AWA promoter Verne Gagne’s radar, during a period when Gagne was auditioning a variety of big men for the main-event role abandoned by Hulk Hogan when he left Gagne’s promotion for the WWF—a menagerie of beefy performers such as “Bull Power” Leon White; the jacked, early-career persona adopted by the future Big Van Vader; and All Japan Pro Wrestling stalwart Stan Hansen, who held the AWA world heavyweight championship for a year wouldn’t return it until the promotion threatened him with legal action. Hansen commented on the young Hall in his autobiography, noting that although he and Hulk Hogan looked similar, Hall was “still very green” and simply not ready to carry a company the way the veteran Hogan could.

That began to change after Gagne paired Hall with savvy second-generation wrestler Curt Hennig. When I came to [the AWA in] Minneapolis, I was green as hell,” Hall said in a Highspots interview. “I’d only been in the business for about eight months. I was bouncing strip clubs about eight months before that. Verne goes, ‘He’s got the look, but he can’t work a lick. … Just put him with Curt.’ They put me with the best worker in the business.”

In January 1986, Hall tasted AWA gold after he and Hennig wrested the tag titles from Jimmy “Jam” Garvin and Steve Regal (the American-born wrestler, not the Blackpool native who recently reemerged in AEW). “Curt influenced a lot of guys—Shawn Michaels, me, Sean [1-2-3 Kid, X-Pac] Waltman—about the way to do business,” Hall explained. “Like, if you’re going to put a guy over, you put him OVER. If a guy is good enough to beat you, man, you make him look like $10 million. Instead of just taking a bump, Curt would do whirly twirls and stuff.”

Hennig also did most of the work, leaving Hall to make the comeback after a hot tag. “Curt did everything then he’d tag me, I’d make the comeback, I’d pin the guy. It got to the point where it was so ridiculous that uneducated fans would go, ‘Hey, Hall, get rid of Hennig, man! Get a new partner—he’s holding you down!’ They had no idea I’d be lost without him.”

After losing the tag straps to “Playboy” Buddy Rose and Doug Somers in May 1986, Hall came up short in title shots against the likes of Stan Hansen and Rick Martel before appearing in the WCW in 1989 as “Gator” Hall, a proto-Skinner (the Everglades denizen portrayed in the WWF by tag team specialist Steve Keirn) who lived on the water and frightened alligators. The WCW was experimenting with WWF-style cartoon characters around this time, like the bell-clad Ding Dongs team of Greg Evans and Richard Sartain, and Hall’s gimmick never got any traction. He did get a lot of in-ring experience, losing matches to star performers such as Mike Rotunda, Terry Funk, and the Great Muta.

Between 1990 and 1991, Hall toured the globe, wrestling for New Japan against top stars such as Bam Bam Bigelow and Koji Kitao; for Otto Wanz’s Catch Wrestling Association during the “Catch Cup ’90” tournament, during which the barrel-shaped Austrian owner finally retired; and for Puerto Rico’s World Wrestling Council, where he won the promotion’s Caribbean heavyweight championship.

In 1991, Hall returned to WCW as “the Diamond Studd,” managed by future WCW world heavyweight champion Diamond Dallas Page, then a wrestling groupie and club owner still learning the ropes himself, but a man who later would play a pivotal role in helping Hall with his addiction. It was there that I took notice of Hall, since he looked incredible and began getting a bit of a push, with wins over former NWA world heavyweight champion Tommy Rich and former Can-Am Connection member Tom “the Z-Man” Zenk. He obviously had the “it factor”—or at least something very much like “it”—and, like Dallas Page, was able to generate considerable heel heat with the disdainful sneers and dismissive gestures he later perfected in the WWF.

This was an interesting period in general for the WCW, which remained a loss leader for Ted Turner while running a distant second to the WWF. The product was not only in flux but also a mash-up of numerous styles either not yet in their ascendance (such as the appearances by skilled competitors from Japan and Mexico) or on the way out (as with the territorial-era approach of the many Southern workers still on the company’s bloated payroll).

On top of that, there was a growing youth movement of talented workers struggling to find themselves, sometimes successfully in the cases of Brian Pillman and “Stunning” Steve Austin, but more often than not unsuccessfully, as in the cases of Hall, Hall’s future Outsider tag team partner and former University of Tennessee basketball player Kevin Nash (who debuted as the bizarre Oz character before transitioning into the equally uninspired Vinnie Vegas gimmick), and Scott Levy (then wrestling as the tanned beach bum Scotty Flamingo, a far cry from the work he did later as Raven). Those three, in fact, were packaged together as Dallas Page’s “Diamond Mine” midcard stable, which paled in comparison to Paul Heyman’s “Dangerous Alliance” that terrorized the company’s good guys and scored a five-star WarGames match at the 1992 WrestleWar. Following a feud with Dustin Rhodes, Hall again left WCW in May 1992. By the time he would return in 1996, he’d be a polished performer—and ready to launch a wrestling war alongside Kevin Nash that would move in a direction neither could predict. But first came the WWF.

Hall signed with WWF that same month, whereupon he needed to sell company impresario Vince McMahon and right-hand man Pat Patterson on the sort of gimmick that could sustain him in a promotion oriented more around muscular, action-figure bodies and cartoon-character personalities. Here, Hall’s career takes a turn for the absurd: He sold them on a character based on his impression of Italian American actor Al Pacino’s impression of fictional Cuban American crime lord Tony Montana from Brian De Palma’s classic 1983 film Scarface. Neither the gimmick nor the name, “Razor Ramon,” foreshadowed future greatness—particularly following Hall’s middling stints as the Diamond Studd and “Gator” Hall—but the skilled performer had paid his dues and was now ready to put all the pieces together.

Hall’s run as Ramon was one of the highlights of the post-Hulkamania “New Generation” era. Alongside Bret Hart, Shawn Michaels, and Davey Boy Smith, Hall redefined the possibilities for mat work within the WWF—never the most welcome place for such innovations, but at a time when the departure of stalwart muscle men such as Hulk Hogan and the Ultimate Warrior forced a reorientation of scope and scale.

In their absence, Hall stood out as a giant on a swiftly shrinking roster. He was still big, now lean and chiseled, and he worked smoothly in the ring. His strength was top-tier, with both his fallaway slam and “Razor’s Edge” finisher—a crucifix powerbomb initially dubbed the “Diamond Death Drop” during his time as the Diamond Studd and later rechristened the “Outsider’s Edge” when he returned to WCW alongside Kevin Nash—executed as smoothly as any moves outside of perhaps Dustin Rhodes’s take on the running powerslam. Nobody strutted to the ring quite like Hall. Nobody fidgeted with a toothpick quite like him. Sure, he was world championship material, but he instead took the WWF’s intercontinental title to its apogee as a belt, a belt that had already grown in prestige during well-regarded title reigns by performers such as Curt Hennig and Bret Hart.

Even then, as a preteen watching Razor Ramon work his magic, I understood that this “bad guy” didn’t need a belt. Sure, there were story lines that went better when he had one, but this was an era when Hall in a story line or on a pay-per-view usually meant money in the bank regardless of what was at stake. His match against Bret Hart at the 1993 Royal Rumble for the world championship was an excellent back-and-forth affair, one of many standouts in which Hall could be counted on to reliably deliver three-star matches per longtime wrestling journalist Dave Meltzer’s work-rate-driven standards. His surprise loss to Sean Waltman—then wrestling as “the Kid” and later as the “1-2-3 Kid” after pinning Hall—went some ways toward making Monday Night RAW into appointment viewing, and also showcased Hall’s willingness, as per his mentor Curt Hennig’s instructions, to put over his friends, making them each look like a million bucks in the process. And his ladder match against Shawn Michaels at WrestleMania X, though neither the first great ladder match nor the greatest when compared to all the intricate, spot-filled matches that followed in its wake, became the first WrestleMania match to earn five stars from Meltzer—a designation it seemed unlikely that the promotion, aimed as it was at the short attention spans of kids and casual fans, would ever earn.

Michaels and Waltman were Hall’s friends, part of a backstage “Kliq” that also included his old WCW stablemate Kevin Nash (wrestling in the WWF as “Diesel”) and future McMahon son-in-law Triple H. Combat sports historian Jonathan Snowden described the group as “a union of sorts in an industry that had no tradition of collective action, working together in a famously cutthroat shark tank to share information and make the most money they could from the bosses.”

It was through the Kliq that Hall made a series of moves that changed wrestling forever, in ways that even Hulkamania before it and the work of Steve Austin and the Rock afterward could not hope to approximate. While Nash and Hall searched for the guaranteed money that the Kliq had always been chasing, Dallas Page caught wind of their dissatisfaction and shared the news with his boss, WCW executive producer Eric Bischoff. In his autobiography, Bischoff explained how guaranteed money landed the pair: “The pitch was, ‘You come over here and you’ll get a guaranteed paycheck, and you’ll work less.’”

After giving their notice but before showing up in the WCW, the Kliq made their first big public move. Following a steel cage match on May 19, 1996 between Shawn Michaels and the departing Kevin Nash, Hall entered the ring and embraced Michaels, which made sense because the two were both good guys and sometimes teammates in an ongoing feud against Nash and Triple H. Triple H then came into the ring and hugged Hall, which broke kayfabe because he and Nash were the heels. All four men then got together, raised their arms in a celebratory gesture that had apparently been approved in some fashion by Vince McMahon, largely because the event wasn’t being broadcast—only to have it recorded by fans who had snuck a camcorder into Madison Square Garden. Stills from the incident hit an internet still in embryonic form, and fans like me—who were already immersed in the RSPW bulletin board and activities such as e-wrestling, a form of wrestling fan-fiction writing—quickly became gossip obsessives. The sport was suddenly and irrevocably meta, with the gossip and the rumors becoming part of the performance itself.

Hall crystallized this change when he made his first appearance on Nitro on May 27, 1996, a mere eight days later. What the heck was happening? Eric Bischoff described in his autobiography how it was laid out, how Hall—already well known within the industry as “very manipulative,” with “a chemical history pretty well known to just about everyone in the business”—walked down through the audience, grabbed a microphone, and began spouting off. “He was a rebel, pissed off, coming back to WCW with a chip on his shoulder,” Bischoff wrote. “The company had held both him and Kevin back, and now they wanted revenge. They were the Outsiders. They had reached a level of stardom at WWE and decided to come back because they’d been disrespected. … He told the audience that he’d been disrespected and intended to fix that by kicking butt. He was coming back next week with his big friend—Nash, though his name wasn’t mentioned—and they intended on taking no prisoners. He looked angry, and the audience responded as if he really was.”

Kevin Nash joined the fray on June 10, and the air of uncertainty that hung in the air until July, when Hulk Hogan turned out to be the “mystery partner” for the so-called “Outsiders” at Bash at the Beach, represented my all-time peak involvement as a wrestling fan. Sure, I followed every swerve that happened thereafter, as did most others, but this month-long period of uncertainty was like nothing that happened before or since. Rumors piled atop rumors; every episode of Nitro was an incitement, driving us to tape its goings-on and then scour it for clues; no stone could be left unturned. And even when the third man turned out to be Hogan, in retrospect a performer far greater than Nash or Hall but certainly less “cool” at the time, the train was already off the tracks. Bischoff wrote that the reason this all worked as well as it did was due to the novelty of the “questions it raised … [because] I’d figured out that the best way to tell the story was to get the audience to ask themselves, ‘what’s going to happen next?’”

The “Attitude Era” that followed, during which an edgy WWF brand championed by the likes of Steve Austin and the Rock helped McMahon’s company reclaim the top spot in the ratings, is often compressed with Nash and Hall’s shocking reappearance in the WCW, but these were two very different things: The latter was built on repeatable swears and slurs, catchphrases such as “suck it” and “roody-poo candy ass,” whereas what WCW under Bischoff, Hall, and Nash was doing was more closely akin to AEW owner Tony Khan’s “Forbidden Door” gimmick—you never knew who would show up, and each new appearance by someone, like Rick Rude appearing taped on an episode of RAW and live on Nitro during the same night in November 1997, was a potential “game changer” until the torrent of supposedly game-changing ex-WWF stars destined for the WCW midcard poisoned the company well.

This was where Hall thrived, because he was a meta performer if there ever was one, sticking with his Scarface-derived “Bad Guy” persona even after he’d lost the actual gimmick and once again become Scott Hall, that most all-American-sounding of surnames. But as Hall improved on the microphone—he was arguably the best of the nWo performers when he was on his game, surpassing Hogan and Nash because he conveyed more with less—he was declining as a performer. In the WWF, he had been a consistently high-level in-ring performer, the sort of perennial intercontinental champion who could open any pay-per-view with 15 or 20 solid minutes against the likes of Jeff Jarrett and Bret Hart. But in the WCW, he wrestled more in tags with Kevin Nash—their SuperBrawl VII match against Lex Luger and Paul “the Giant” Wight is a great match—and though he held the company’s second-tier United States championship on two occasions, he never claimed the world heavyweight championship.

At his peak, Hall certainly deserved that world strap, but he had been wrestling for more than a decade and was cresting the hill if not yet entirely over it, with injuries and addiction catching up to him. He was sent to rehab after showing up intoxicated on an episode of Nitro alongside Kevin Nash in March 1998, and this was the start of the tumultuous final period of his career. Hall was falling forward, and though there was still plenty of net left to catch him, he now lacked the means to return to the absolute pinnacle of the sport. His crash caught me by surprise, since I knew nothing at the time about his early life, and failed to take note of contemporaneous stories about how he was arrested in 1998 for groping a 56-year-old woman outside a Louisiana hotel.

Whereas I assumed Hall had flamed out suddenly, the process was much more gradual—he had been on the downslope for years. Colleagues who weren’t as devoted to him as Nash and Sean Waltman were found him difficult to work with; “Hacksaw” Jim Duggan called him “one of the most detrimental guys a company could have” in his autobiography, and Chris Jericho observed in his book A Lion’s Tale that “the combination of power and substance [misuse] had turned [Hall] into a real asshole.”

After his departure from WCW in February 2000, Hall made a brief appearance during the last days of ECW in 2000 before heading back to New Japan for matches against top superstars like Keiji Mutoh and rising stars like Hiroshi Tanahashi. He reappeared in the WWF in 2002 in what seemed like a promising revival of the nWo—already, the nostalgia clock was ticking, but I tuned in to watch Hall’s brief feud with Steve Austin, which culminated in an unmemorable match on the same WrestleMania X8 card on which the crowd turned “Hollywood” Hogan into a good guy again, with his match against the Rock propelling him to the last great run of his storied career. Hall, meanwhile, lingered for two months thereafter, until he was fired for his role in the May 2002 “Plane Ride from Hell”—initially an event portrayed as a sort of comic sideshow to the excesses of the “Attitude Era” until a recent Dark Side of the Ring episode demonstrated its more problematic aspects. Accounts of harassment by Hall were certainly no laughing matter, and underscored his struggles outside of the ring.

Hall’s work thereafter pales in comparison with his “New Generation” standard. His 2002 and 2004 runs in TNA were interesting because you could watch, both in his 2002 NWA world heavyweight title match against Ron “R-Truth” Killings and his loss to Jeff Hardy at Final Resolution, exactly how he was losing his edge: visibly paunchier with each appearance, still able to do a convincing fallaway slam but far less steady with the “Razor’s Edge” finisher than before. By the time he was back to mostly wrestling in tag team matches with Kevin Nash in TNA in 2010, he looked positively ancient, with the also-aging Nash left to pick up the in-ring slack for his best friend until he and Hall were stripped of the tag titles due to Hall’s ongoing legal problems and burgeoning substance misuse.

Hall’s outside-the-ring travails could fill an entire book, and range from attacking a comedian who told an off-color joke about Owen Hart at a 2008 roast of the Iron Sheik to being arrested for choking his girlfriend Lisa Howell in 2012—not to mention his inebriated appearances in the ring, such as the incoherent and extremely depressing 2011 indie appearance described in the E:60 documentary, when the promoter dragged him out to the ring in lieu of refunding fans who had paid to see him. His health problems were legion, ranging from the multiple trips to rehab financed by the WWE, heart issues that necessitated the implantation of a pacemaker and defibrillator in 2010, and epileptic seizures that upped his daily prescription medication count into the double digits. He was a dead man walking—bloated face, battered body, pipe-cleaner legs—until he reconnected with longtime friend Dallas Page in 2013, during which time Page helped Hall get sober, in a process that serves as the b-plot but also the more interesting story line in the 2015 documentary The Resurrection of Jake the Snake (perhaps because Jake Roberts’s own ongoing addiction had been so extensively chronicled, dating back to the 1999 documentary Beyond the Mat).

Given all the damage already done to his system, Hall’s recovery was no guarantee of a long life, but he managed a few additional highlights in his declining years. His 2014 WWE Hall of Fame induction speech showcased Hall looking as good as he ever would again, packing gravitas into every syllable as he reminded the crowd that “hard work pays off, dreams come true, bad times don’t last, but bad guys do”—a fitting epitaph delivered eight years before the end. He would go into that Hall of Fame a second time as part of the class of 2020 for his part in the nWo, but his first speech is what everyone remembers. It’s a poignant moment, an altogether too brief reminder of a great career that tantalized his closest friends and most fervent fans with promises of what could have been.

But those promises were merely daydreams, castles in the air. Scott Hall grew up the son of a father with alcoholism, who warned him about what his future held, then came of age during a moment of violence, the trauma of which he could never shake. “People think Scott’s problem is he likes to get drunk and likes to take drugs and he’s an addict and he’s not,” Kevin Nash explained on the Live Audio Wrestling show in 2011. “He has PTSD and had several incredibly horrible incidents happen in his early youth going on to his adolescence and early adulthood and he has had things happen to him that he cannot get through.”

We might have assumed Hall was soaring, but he was merely falling forward, briefly held aloft in the air like a hapless opponent suspended at the precipice of his Razor’s Edge.

Oliver Lee Bateman is a journalist and sports historian who lives in Pittsburgh. You can follow him on Twitter @MoustacheClubUS and read more of his work at www.oliverbateman.com.