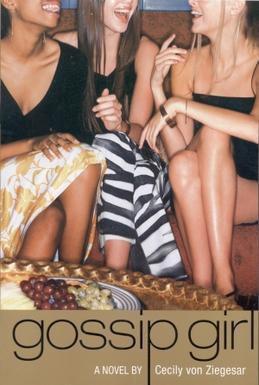

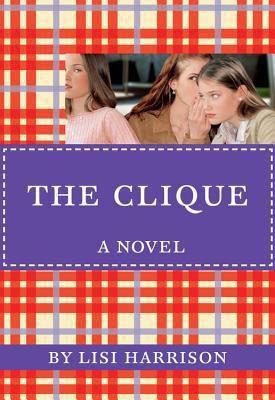

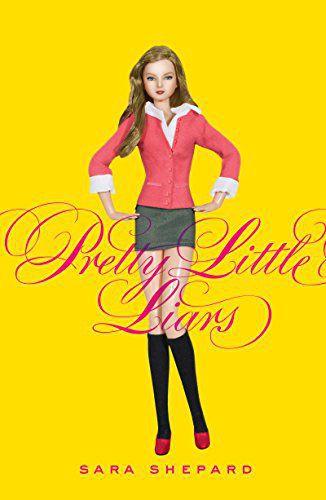

When Sophie Krueger was growing up in Ohio in the early 2000s, she’d often make unsupervised trips to the bookstore. There, she was free to choose what she wanted to read in her free time—not her teachers; not her parents; just her. In the section marked “Young Adult,” Krueger found herself drawn to a particular series of images. A tween girl whispering in another’s ear, their photo framed in bold, preppy plaid. A Barbie-esque doll against a bold yellow backdrop, dressed in a miniskirt and knee-high socks. A group of young women laughing at some inside joke, their faces mysteriously cut off below the eyes.

The designs were alluring, almost intimidating. They were a far cry from the fuchsia pinks and frilly fonts often deployed to target girls around Krueger’s age. “Those girls are showing leg on the covers,” Krueger, 24, now says. “It looks like you’re picking up Vanity Fair magazine, rather than something an 11-year-old should be reading in bed with a flashlight.”

In this case, she was right to judge these books by their covers. The books Krueger and her peers devoured more than a decade ago—Gossip Girl, The Clique, The A-List, Pretty Little Liars, Private—had their differences, but all were bitchy, addictively dramatic, and chock-full of luxury brand names. These books’ implicit values were very much of their Bush-era, pre-recessionary time, and impressionable readers, many of them girls, soaked them up like a sponge. Together, they formed a crash course in socioeconomic status and platonic hierarchies at an age when those dynamics were about to become all-important.

Krueger didn’t know it at the time, but those books didn’t share just a sensibility. The novels were the product of the series’ individual authors but also of the company that commissioned their bestselling work: a firm called Alloy Entertainment. Beginning at the turn of the century, Alloy played a role in establishing the industrial complex now known as YA, located in the nebulous space between children’s books and adult literature. It would do so, in part, by treating kids, and especially girls, like adults: as consumers with a grown-up’s desire for escape and entertainment but also a child’s curiosity and need to belong. Twenty years ago this month, Alloy launched the book that would solidify that approach, creating a generation of readers entranced by an in-the-know voice that didn’t care about kindness, for better or for worse. Many series would take on that tone in its wake, but then and now, there’s only one Gossip Girl.

“It’s funny,” reflects Gossip Girl’s author, Cecily von Ziegesar. “When I’m talking about Gossip Girl these days, it’s usually like, ‘There were books?’” Gossip Girl has since transcended its origins to become a cultural phenomenon, the kind a global conglomerate will attempt to make the centerpiece of its new, ambitious streaming service. Beginning in 2007, the CW’s adaptation became a gargantuan success, making tabloid stars of its cast and weekly games of its references to New York’s elite as seen through the eyes of its most privileged high schoolers (and one anonymous blogger). The show ran for six seasons before HBO Max revived the concept as an even more opulent, diversified reboot that will return for a Season 2. Two decades in, the franchise has yet to run out of steam.

Pretty Little Liars, too, became a TV hit that eclipsed its inspiration. The teen soap on ABC Family, now Freeform, began in 2010 with the same mystery as Sara Shepard’s books before eventually outstripping their plot: the mysterious disappearance of Alison DiLaurentis, golden child of the Philadelphia Main Line. After running for seven seasons and launching the careers of actors like Spring Breakers’ Ashley Benson, the show has since produced multiple spinoffs. The third, titled Pretty Little Liars: Original Sin, will soon join Gossip Girl on HBO Max.

Much like the parallels between the original books, the success of Gossip Girl and Pretty Little Liars as TV franchises is not a coincidence. Managing and retaining ownership of its titles’ IP has been part of Alloy’s business model since its current CEO, Leslie Morgenstein, acquired the company then known as 17th Street Productions with his former business partner Ann Brashares—author of The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants—in 2000. Alloy began as a book packaging company, a kind of middleman between writers and publishing houses that oversaw long-running series such as Francine Pascal’s Sweet Valley High. Under Morgenstein’s leadership, it’s also become something of an assembly line, shepherding stories from the page to the screen.

Alloy has employed this approach with a wide variety of subgenres within YA. It’s the force behind the reissue of The Vampire Diaries, jumping on the supernatural romance craze that followed Twilight, as well as The 100, the allegorical postapocalyptic drama that works within the template established by The Hunger Games. Both shows began as books and then aired on the CW, a natural partner in Alloy’s quest to cater to teens who crave a certain high-gloss finish. In 2012, Alloy was acquired outright by Warner Bros. Television Group, which shares a parent company with both the CW and HBO Max. (The CW, technically a joint venture between WarnerMedia and ViacomCBS, is currently up for sale.) Alloy has even expanded beyond YA; its current crown jewel, the Netflix sensation You, is based on an adult novel by author Caroline Kepnes. In a true full-circle moment, You’s lead actor, Penn Badgley, once played the character revealed to be the titular Gossip Girl.

Back in the mid-aughts, though, Krueger had no idea her taste in reading was part of a larger design. She just clicked with the house style, which she now dissects in depth on Girls Like Us, the podcast she cohosts with friend and fellow comedian Frannie Comstock that reevaluates these young adult series with adult-adult eyes. If Gossip Girl was a gateway drug, Alloy readily supplied substitutes to keep young readers hooked. The log line for The Clique—which sold a staggering 6 million copies by 2008—is essentially “Gossip Girl with middle schoolers”; The A-List is “Gossip Girl in L.A.”; Private, “Gossip Girl at boarding school.” When I bring up The Luxe, a title from 2007, Morgenstein instantly responds, “Turn-of-the-century Gossip Girl!”

On Girls Like Us, Krueger and Comstock take an approach that’s both critical and compassionate, noting what hasn’t aged well—the materialism and blinding whiteness—while also understanding what made the micro-genre so appealing. After all, part of growing up is coming to understand that taste isn’t entirely reflective of personal instinct, though the canniest products make you feel like it is. “These books are part of a larger machine,” Krueger notes, “and there’s no better metaphor for that than all of these books getting funneled through the Alloy Entertainment heading.”

Most young readers—and adult ones, for that matter—have no idea what a book packager is or does. In children’s literature, the practice dates back to the early 20th century, when Edward Stratemeyer and his namesake syndicate inaugurated an empire that would grow to include seminal series like The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew. Rather than an author and their agent selling a manuscript directly to a publisher, packagers serve as a liaison between the two, developing ideas and recruiting writers to facilitate quick, consistent output. “A good analogy is a showrunner,” Morgenstein says of the traditional model. “We’re controlling all the material, hiring the ghostwriters, and ensuring creative consistency.”

It’s funny. When I’m talking about Gossip Girl these days, it’s usually like, ‘There were books?’Cecily von Ziegesar

When Morgenstein took charge of what’s now Alloy, he detected a potential gap in the market. “This was the mid-to-late ’90s,” he recalls. “Boy bands were huge. The WB had launched and was very successful at the time. Teen People was successful as well. And the book business wasn’t tracking with all this other teen media and entertainment.” The same demographic that was tuning into Dawson’s Creek needed a backup for when their parents ordered them to turn off the TV and read a book for once. And they didn’t want that book to feel like homework. “The audience was sophisticated and wanted to be cool,” Morgenstein says. “The books weren’t.”

Alloy moved to meet this untapped demand, developing book ideas in-house with the aim to supplement sales by licensing film and TV rights, which it would control by retaining the IP. Writers would retain a share of the books’ revenue—on average, Morgenstein says, about 50 percent—but Alloy would maintain a much stronger hand than the typical publisher, reviewing detailed outlines and acting as a full creative partner. In fact, the first two major hits of its new era were written by members of the editorial staff. One was Brashares’s The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, a coming-of-age story that dealt with mature themes and was an affirming story of female friendship. (The film version’s cast included future Gossip Girl star Blake Lively.) The other was Gossip Girl.

Von Ziegesar was a graduate of Nightingale-Bamford, a private girls’ school on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. So when the Alloy brain trust latched on to a report in The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town section about the neighborhood’s teens trading scandalous stories in online chat rooms, she volunteered to take a crack at a treatment. (Alloy sells book ideas to publishers on the basis of partial manuscripts.) “It was like this voice I didn’t even know I had,” von Ziegesar says of the series’ seen-it-all, done-it-all narration, the basis for Kristen Bell’s iconic voice-over. “It’s like everything that you’re thinking about, but you don’t say.”

After an epigraph from Oscar Wilde (“Scandal is gossip made tedious by morality”), the first page of Gossip Girl includes references to sex (the Upper East Side is “where my friends and I live and go to school and play and sleep—sometimes with each other”), profanity (“Our shit still stinks, but you can’t smell it because the the bathroom is sprayed hourly by the maid”), drinking (“Even with a hangover, Fifth Avenue always looks so beautiful”), and more sex (“Our parents are rarely home, so we have tons of privacy”). Anne of Green Gables it wasn’t. The lived-in sense of detail came from von Ziegesar’s own experience, but in a textbook case of Alloy’s anti-auteur ethos, the title came from a summer intern’s nickname for her sorority sisters.

The same bad behavior that made Gossip Girl compulsively readable also made it a tough sell for publishers, who had a hard time squaring the characters’ adult antics with their intended audience. Eventually, Little, Brown and Company signed on, inking a deal for four books in less than two years. After two, von Ziegesar left the Alloy staff as an editor to write full-time. The third made the New York Times bestseller list before it even hit the shelves. Von Ziegesar remembers seeing a magazine spread featuring everyday teens on Long Island in which one mentioned reading Gossip Girl. It was the first time she’d come across a reader organically.

A first-time novelist, von Ziegesar wasn’t the only writer Alloy recruited with a less-than-conventional literary background. Jeff Gottesfeld, half of the formerly married writing team that penned The A-List under the pseudonym Zoey Dean, came from the world of soap operas, a “meat grinder” that prepared him for Alloy’s quick schedule and twisty plots. Shepard of Pretty Little Liars was in her 20s and freshly out of an MFA program when her sister, an intern at Alloy, put her in touch with the company. Before she published under her own name, Shepard ghostwrote for other Alloy series—including the first installment of Gossip Girl spinoff The It Girl, which featured future Trump aide Hope Hicks as the cover model. Some attempts to replicate Gossip Girl’s success were more direct than others.

Lisi Harrison, author of The Clique, was working in development at MTV when she met with former Alloy editor Ben Schrank to discuss potential projects. In theory, Harrison was looking to buy material from Alloy, but the arrangement ended up the other way around. “I remember Ben saying, ‘Do you have any interest in writing literature?’” Harrison recalls. “I said, ‘No, I don’t want to write literature. I want to write books people will read!’” Harrison had initially bonded with Schrank over how MTV’s office politics were just like middle school. Eventually, she’d cut to the chase and write about middle school. Harrison then created Octavian Country Day (OCD for short—a joke that doesn’t quite land in 2022), the Westchester County private school the snooty Massie Block and her Pretty Committee rule with an iron fist.

Given Alloy’s intent to treat adolescents like pint-sized adults, its authors’ influences weren’t limited to their peers in teen media. The rise of Gossip Girl and its ilk coincided almost exactly with the peak of so-called “chick lit,” the somewhat derogatory term for mass-market fiction aimed at female readers. “There was talk about these books as junior chick lit,” says Amy Pattee, a professor of children’s literature and library science at Simmons University who has published writing on both Gossip Girl and The Clique. “That kind of entertainment for, presumably, cisgendered women was coming to the fore in the adult world, and Gossip Girl was something that seemed to be not unlike that.” What Bridget Jones’s Diary was to the woman on the go, Gossip Girl was to her niece just figuring out what womanhood might look and feel like.

When von Ziegesar was first developing the Gossip Girl persona, she wasn’t thinking about the books’ potential impact on their audience. In fact, she assumed there wouldn’t be much of an audience at all for a story centered on a single ZIP code. “I’m not going to worry about ‘Am I offending anybody? Is this right? Is this wrong?’” she says now, walking through her thought process at the time.

Several years later, the Gossip Girl show would run an indelible ad campaign repurposing complaints that the drama was “mind-blowingly inappropriate” and “every parent’s nightmare.” Long before that, von Ziegesar would go on The Today Show alongside a clinical psychologist to debate if her creation was “too racy” for its target demographic, and the feminist writer Naomi Wolf penned a pearl-clutching op-ed about its ilk for the The New York Times. “Unfortunately for girls,” Wolf wrote, “these novels reproduce the dilemma they experience all the time: they are expected to compete with pornography, but can still be labeled sluts.” Not all highbrow observers were so disapproving, though; in 2008, the legendary journalist Janet Malcolm published an earnest tribute in The New Yorker.

I remember Ben saying, ‘Do you have any interest in writing literature?’ I said, ‘No, I don’t want to write literature. I want to write books people will read!’Lisi Harrison

Ironically, Gossip Girl was far less explicit about sex than, say, Judy Blume, the godmother of YA, or Rainbow Party, a sensational novel published in 2005 that illustrated parents’ worst nightmares. (The title referenced an urban legend about color-coded blow jobs.) “For us, that is not something we would want to pursue,” Morgenstein says of Rainbow Party. “The raciness cannot be what the thing is about.” But Gossip Girl constantly alluded to sex and sexuality, even if the narration cut away before anything got too graphic. The same goes for eating disorders, drug use, and a general fixation on weight, appearance, and social hierarchies. In one of the novel’s fictional blog posts, Gossip Girl spies on two tertiary characters: “Caught I. and K. in the 3 Guys Coffee Shop, eating fries and hot cocoa again. They’d just returned those cute little dresses they’d bought at Bendel’s the other day—oh dear, are they getting too fat?”

“There was material in Gossip Girl and The A-List that would not have been touched even 15 years before,” Gottesfeld notes. Those 15 years saw the invention of YA as a genre separate and apart from both children’s and adult literature. The transition to this new market could be an awkward one; von Ziegesar remembers giving a reading next to toddlers doing storytime after one bookstore assigned her to the kiddie corner. Still, the novelty helped Alloy get in on the ground floor and differentiate itself from its more juvenile competitors in youth-oriented publishing. Most middle-grade books don’t include references to the Cuban French erotica writer Anaïs Nin, as The A-List did.

That distinction wasn’t just a matter of what was depicted, but how. “I really resisted books as a young adult that felt like they were teaching me something, because I didn’t want to be told what to think,” von Ziegesar says. So when it came time to write her own young adult novel, “that was like, number one: I was not going to teach any lessons.” Reading Gossip Girl and its successors felt like being let in on grown-up secrets that parents couldn’t or wouldn’t tell you. “I knew the lessons that loving, caring adults in my life had taught me: ‘No, your worth isn’t connected to your looks, and you should just be yourself,’” Comstock of Girls Like Us says. “These kinds of books were the direct opposite, but that almost felt more truthful to me in the world that I was living in.” Other kids’ books could feel like a lecture, but Gossip Girl and The Clique felt like their own kind of how-to manual: buy this brand to fit in; hurl this insult to make your enemies feel bad about themselves.

In lieu of an authority figure, the books felt like they were coming from a cool older sister, partly because they were. Most of Alloy’s authors were young women not too far removed from the intended age of their audience, allowing them to write in a language kids could understand—and without a parent’s concern for the messages they might be sending. “I was single, childless, working at MTV,” Harrison says of her mindset when writing The Clique. “I didn’t even know kids lived in New York City. … I wasn’t writing as an adult. I was writing as a sassy teenager.” She was also writing what she knew. Harrison and her fellow authors were ultimately swimming in the same cultural soup as everyone else in the aughts.

Even more than most bygone trends, the Gossip Girl generation of YA books feel extremely of their time. Post-9/11, pre-Obama, this was a moment when mass media was dominated by diet culture and fatphobia while lacking diversity in young adult literature and elsewhere. The past years have seen a collective reevaluation of the aughts, particularly their attitudes toward women. Such case studies have tended to center famous individuals, from Britney Spears to Janet Jackson to Lindsay Lohan, and frame them as the victims of larger institutions. But those institutions, including the media, are also made up of individuals capable of self-reflection.

“I look back on the things that I wrote and I cannot believe what I a) did and b) got away with,” Harrison says. “Which is a sign of where I was at at the time, but also a sign of where we were culturally and how far we’ve come since then.” Harrison still writes YA novels for Alloy, but now that she has kids of her own, she describes their tone as “slightly more sanctimonious.” But even as she recognizes what hasn’t held up, Harrison tries not to hold herself uniquely accountable. “It’s definitely a commentary on not just where the authors were, but where our culture was,” she says of the Clique books’ success. “Because in order for them to do that well, there was an appetite for it. So we all have grown and changed.”

All trends must pass, and “chick lit for kids” was no exception. When the economy crashed in 2008, an open embrace of consumerism no longer held the same appeal. An awareness of inequality and other social issues began to reassert itself in YA storytelling through phenomena like The Hunger Games and Divergent. “That was such a politically different, one might say diametrically opposed, product,” Pattee, the professor, says. “We had another wave, or a different wave, taking over.” Meanwhile, romances like Twilight provided an escapism much more pure and total than modish brands and their luxury products.

“We definitely did not have a strategy session where we said, ‘The end is coming. Let’s pivot away,’” Morgenstein says. Alloy still managed to ride this new wave, reviving The Vampire Diaries—the book series’ first four installments were published in the 1990s—and publishing titles like Nicola Yoon’s The Sun Is Also a Star, in which a teen falls in love while facing deportation. (The 2019 film version starred Yara Shahidi.) Still, the likes of Gossip Girl and Pretty Little Liars live on in the form of their high-profile adaptations.

With its libertine attitudes, cosmopolitan setting, and convivial narrator, Gossip Girl evoked the smash hit Sex and the City, which helped turn HBO into a powerhouse in the late ’90s. Meanwhile, Pretty Little Liars originated with a pitch from one of Alloy’s TV executives, who wanted to make a play on Desperate Housewives for teens; The Clique started when Josh Bank, now Alloy’s East Coast entertainment president, wondered what it might look like if Tony Soprano were a middle-school girl. Alloy had exploded around the same era television began to reorient itself around unrepentant antiheroes, teaching audiences not to expect or even enjoy model behavior from their protagonists. It was only a matter of time until Alloy’s characters joined their ranks.

More than most Alloy projects, Pretty Little Liars was built for the screen. After originating with a pitch from the company’s TV wing, Shepard’s first book and the pilot were developed in tandem with each other. “I had maybe written a draft of the first one and it was optioned for TV, which was funny,” Shepard recalls. The show wouldn’t debut for another four years, but that had more to do with Hollywood’s slower pace and higher barrier for entry than an intentionally staggered approach. The dual development was a hint of where Alloy was headed: skipping the intermediary steps and workshopping projects directly for film and TV. Alloy’s best-known properties are still the ones that originated as books, but its CV is now dotted with entries like the Netflix movie Work It that got a green light sans source material.

I knew the lessons that loving, caring adults in my life had taught me: ‘No, your worth isn’t connected to your looks, and you should just be yourself.’ These kinds of books were the direct opposite, but that almost felt more truthful to me in the world that I was living in.Frannie Comstock

Such an expansion was always a part of Morgenstein’s long game. The UPN series Roswell, now reimagined as Roswell, New Mexico, was based on the book series Roswell High, a 17th Street title that predated Morgenstein’s IP-ownership model. When talking with one of the producers about their job, Morgenstein had an epiphany: “That’s similar to what we do. We obviously do it in the book world in New York, but this feels like a job we could do in L.A.” The entertainment industry is hardly open to outsiders, so gaining a foothold was a yearslong process, but in 2022, Morgenstein describes film and TV as “the more substantial part of our business.” As publishing in general has declined in the past two decades, it’s also become a smaller share of Alloy’s overall enterprise, though the company still puts out around 20 to 25 new volumes a year. Morgenstein, a former New Yorker, is now based in Los Angeles.

Some of Alloy’s early successes survive, if in altered form. Last month, Shepard announced The Liars, an Audible Original that follows her four original heroines into adulthood. Harrison has an outline for a novel about The Clique’s Pretty Committee as 20-somethings, though she’s had trouble convincing publishers there’s interest. (There’s a Change.org petition to sign if you disagree.) But, then as now, the standout is still Gossip Girl, whose strained reboot still managed to break HBO Max viewership records last year. In its newest iteration, which tries to be both gleefully bitchy and pointedly PC, the show feels as conflicted in its stance toward the original setup as many of its adult fans.

When showrunners Josh Schwartz and Stephanie Savage first took on Gossip Girl, von Ziegesar took the latter on a guided tour of the Upper East Side: a meal at Fred’s, the restaurant inside Barney’s (RIP) where the books’ not-quite-yet-ladies would lunch; a walk through Central Park, where Serena and Blair would tan on Sheep Meadow while cutting class; dismissal at Nightingale-Bamford, when the school’s hundreds of students would be released into the wild. From there, it’s entirely possible some of those students went home to read about the latest developments in the lives of their fictional counterparts. The books may not have been what their teachers had in mind, but they were books they chose to read.

“Fundamentally, I think anything that gets kids reading is a great thing,” says The A-List’s Gottesfeld. “To have kids reading, and particularly teens reading, and talking about books as if they’re real—that’s a good thing.”