The Goodman Experiment

When he was added to the ‘Breaking Bad’ ensemble, Saul Goodman wasn’t intended to be a spinoff character. So how did he end up with his own show, ‘Better Call Saul’? Allow Bob Odenkirk and the team who brought Saul to life explain in this oral history.Listen to this oral history on The Prestige TV Podcast.

A lawyer named Saul Goodman? Bob Odenkirk didn’t think he was right for the role. When Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan called to offer it to him back in 2009, he almost said no.

“He starts talking about the character,” Odenkirk says. “And I go, ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa. Saul Goodman?’ I said, ‘Yeah, just so you know I’m not Jewish. And I said, ‘There’s a lot of pretty good Jewish actors in Hollywood. I think you can find somebody.’”

What Odenkirk didn’t know, and Gilligan explained, was that Goodman was actually a silly pseudonym picked to attract clients. “He goes, ‘Oh well, he’s not Jewish either. He’s Irish,’” recalls the actor, writer, comedian, and filmmaker. “And I go, ‘Oh, OK. Well, so am I.’ I’m half-Irish.”

Once Odenkirk learned Saul’s true heritage, he moved on to more important matters. “Then Bob started talking about his hair,” says executive producer and future Better Call Saul cocreator Peter Gould, who was also on the phone that day. “And this is my introduction to something about Bob that I didn’t know, but now makes perfect sense. Bob is just a genius at thinking about how his character looks. And especially hair.”

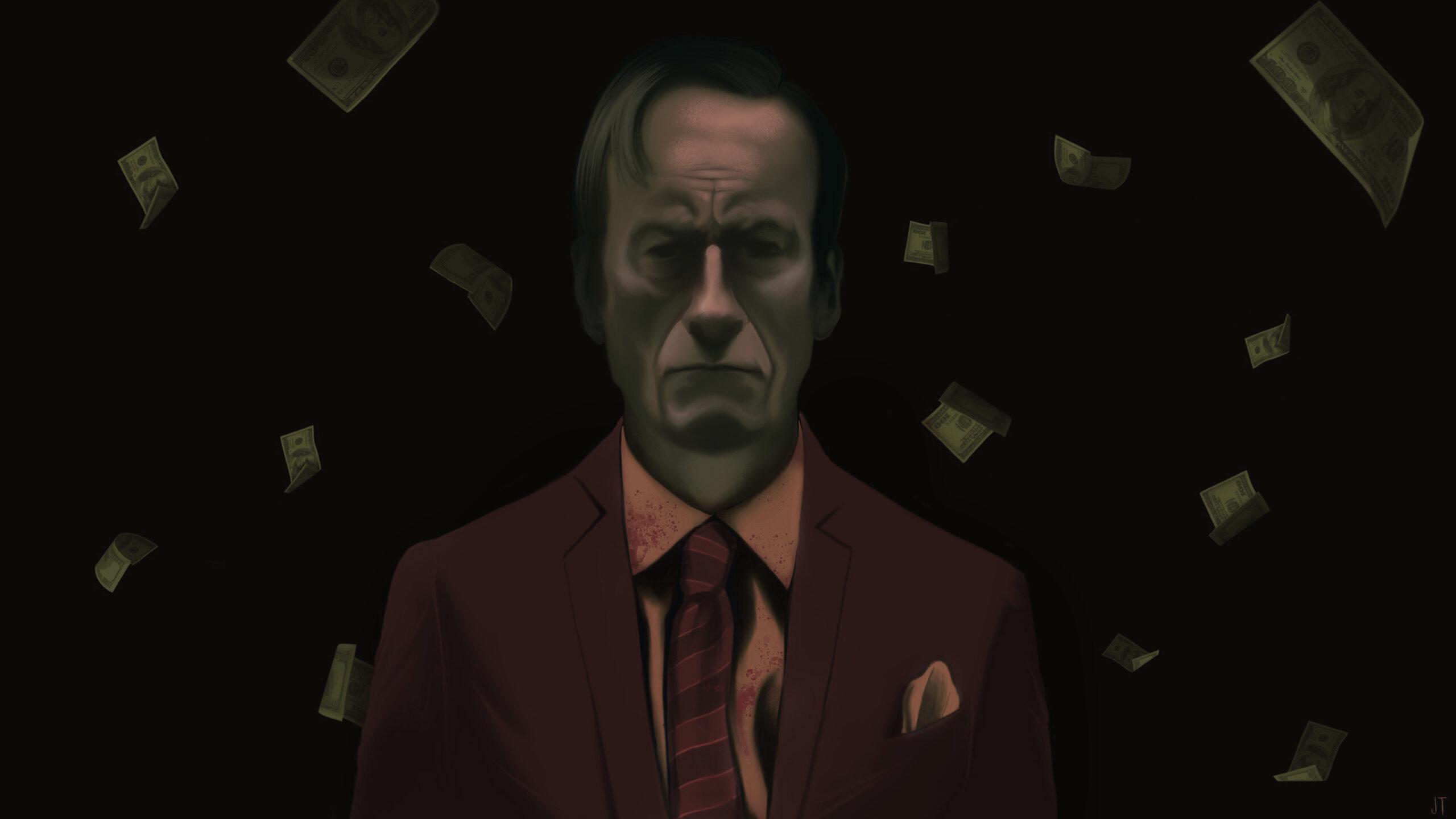

Saul Goodman had a toupee. He wore colorful suits and a pinky ring. And he drove a boat-sized Cadillac. On the surface, he was a cartoon attorney—the kind that may have even popped up in the ’90s on Mr. Show, the beloved sketch comedy series Odenkirk created with David Cross. Yet there was much more to Saul than that.

But at the beginning, no one could see it. Originally, Saul Goodman was only guaranteed to stick around Breaking Bad long enough to get wannabe meth kingpin Walter White and his partner Jesse Pinkman out of a legal jam. After that, it was unclear where he’d end up—maybe in a shallow grave somewhere in the New Mexico desert. In fact, Gould even remembers Odenkirk asking him whether the writers were going to kill off Saul quickly.

“I said, ‘No, I think we like this guy,’” Gould says. “There’s something a little bit throwbacky about Saul. There’s something a little bit classic Hollywood scamster, a little bit of martini-glass-and-Playboy-magazine kind of quality to the guy.”

Not long after Saul made his debut midway through Season 2 of Breaking Bad, it became very apparent that he was more than just comic relief. Even before the AMC series wrapped in 2013, Gilligan and Gould were talking about a Saul Goodman spinoff.

“He was able to plant his flag in an established show, written by a team of writers who were so compelling and convincing and intriguing,” says Breaking Bad star Bryan Cranston. “Once they saw Bob and this character that he was bringing to it, they opened up to it and said, ‘Oh, there’s more. Oh, there’s still more. Oh, there’s even more.’ And it just kept widening. And that was the birth of Better Call Saul, through Bob’s ability to carve out his piece of the pie.”

With Better Call Saul entering its sixth and final season this month, it’s time to tell its namesake’s unlikely origin story. This is how Bob Odenkirk turned Albuquerque’s favorite criminal lawyer into one of the most iconic characters on TV.

Part 1: “Well, You Call a Lawyer.”

By the time Breaking Bad premiered in January 2008, Odenkirk had long since established himself as a legendary comedy writer and performer. He’d also piled up credits as an actor, director, and producer. But he was still looking for the kind of passion project that had eluded him since the days of Mr. Show.

Bob Odenkirk (Saul Goodman/Jimmy McGill): The way that went down was my agent called and said, “They’re going to offer you a role on Breaking Bad. Don’t say no. It’s the kind of role that someone wins an Emmy for.” And I said, “All right, well, let me think about it for a minute.” And then I called a friend, Reid Harrison, and I said, “Do you know anything about this show Breaking Bad?” And he was like, “Oh, my God, it’s the best show on television.” Very few people had seen it. And nobody talked about it that I knew.

Reid Harrison (comedy writer): My immediate reaction was kind of like, “All right first of all, hang up, you shouldn’t be talking to me. You should be calling back right now and taking it.”

Peter Gould (Breaking Bad executive producer/Better Call Saul cocreator): Pretty early in Season 2, the idea came up that Walt and Jesse would have to sell drugs themselves. They didn’t have Tuco to just hand in a bag of cash for the drugs. And of course the next thing you think is, “Well, if you start having Jesse’s idiot friends selling drugs on the street, they’re going to get caught. And what happens when one of them gets caught? Well, you call a lawyer.” And so it started off very much as a piece of story-problem solving.

One day Vince walks in and says, “What if the lawyer they go to is a guy named ‘Saul Good’ and he’s kind of a little bit of a scammer himself.” And then one of the other writers said, “Well, Saul Goodman.” And then somebody else said, “Well, what if he had a ‘LWYRUP’ license plate?” And we just started having fun talking about this character. Pretty soon the idea of the bus benches and all the different things that he gets into started materializing, but they were all in service of the Walter White story. We weren’t adding him in because we thought it would be a fun spinoff character.

Bryan Cranston (Walter White): This dubious, fast-talking, slick, unctuous kind of character.

Harrison: Bob is unique in the way that he is funny. In a really clever, slightly unpredictable way. That role was really perfect for him.

Gould: We came up with a list, my wife put at the top of the list, “Bob Odenkirk.” And you know who else put the name at the top of their list was Bialy/Thomas, our casting folks. And Vince and I were both huge fans of Bob’s from Mr. Show, especially.

Odenkirk: There’s a few scenes in Mr. Show I could point to and say I show some chops as an actor, some ability to lose myself and with a degree of modulation and sensitivity, but not much. Mostly it’s sketch comedy. And you can be pretty goddamn broad in sketch comedy. You can even break in sketch comedy and the audience doesn’t mind.

Cranston: I was well aware of Mr. Show and that was cool. I have years of comedy improv behind me, as well. And I was a very short-term stand-up, for nine months, actually. I reached the level of mediocrity in my quest. And I realized at a certain point I didn’t have the love for it, so I bailed.

Bill Burr (Patrick Kuby): I went to a taping of Mr. Show. I had watched sketch comedy my whole life and I never saw one sketch lead into another sketch. And there was singing. I remember David Cross singing as this redneck. I just remember thinking that it was such a good thing to be exposed to, the bar being that high.

Odenkirk: What surprised me is that they gave me the part because of Mr. Show. I thought—and I never said a word about it, because I didn’t want to create a kerfuffle—they gave me the part because I played [agent] Stevie Grant on Larry Sanders.

And I was sure that one day, Vince would tell me the story of how he saw me on Larry Sanders, and that’s what gave him the idea. But the truth is Peter wrote the first episode that featured Saul. And he wrote a lot of the character’s runs and a lot of the ways in which Saul talks and is funny.

Burr: There’s a lot of comedians getting dramatic work now. And I feel like Breaking Bad was at the forefront. I remember we were doing a scene and it was me, Lavell Crawford, an amazing stand-up comedian, and Bob Odenkirk. And we were in his lawyer office, which was iconic. To me that was the Seinfeld diner. I couldn’t believe I was sitting there. And we had the top of the scene. It was just the three of us before Mr. White came in and I remember sitting down and thinking to myself, “For the first 30 seconds of this scene, three stand-up comedians are going to be holding down the best drama on television right now.” I was like, “How fucking cool is this?”

Gould: There’s always a comic element to both shows. And, we always say that it’s a little bit like peanut butter and chocolate. They make each other taste better. And I think if there is a secret sauce to both shows, I think that’s certainly part of it. Because, the drama makes the comedy funnier. I don’t think the comedy on either show would stand by itself as comedy, but the comedy certainly makes the drama more dramatic.

Part 2: “Look at What We Get to Do!”

Saul Goodman was a true original. But to fully get into character, Odenkirk needed a bit of inspiration. He drew it from famously loquacious Hollywood producer Robert Evans’s memoir, The Kid Stays in the Picture.

Odenkirk: I would still rehearse by doing the Evans voice in my trailer, doing Saul runs. Once I knew the lines, I would do it as Evans. And I don’t know how much it informed my own performance in the end, because I didn’t try to do a Robert Evans impersonation. But I had read his book twice. I’d listened to his book on tape twice all the way through. This is a guy who could talk and talk and really entertain you. And what I found was a kind of a singsong that doesn’t get repetitive. He’s very good at breaking things off and cliffhanger pauses and moments.

And if you’re going to listen to me talk for five pages, I’ve got to be doing something interesting, saying something interesting, but also working it, working that material. So, Evans was to me an entertaining speaker, and he knew how to sort of choreograph his words and his tonal shifts to intrigue you. I think maybe, hopefully, I got something from that. At the very least, I entertained myself.

Jonathan Banks (Mike Ehrmantraut): My first impressions of Bobby? I thought he was a little nervous. But that went along with the character. That was definitely Saul.

Cranston: There were things, little hooks, little connector lines that he was able to add to trapeze himself from one line to the next line to the next. That’s always really good for an actor to feel confident in being able to connect thoughts. The gift of gab, he was able to bring that.

Banks: I love it when Bobby plays the bewildered, put-upon, “I don’t know what ever I’m gonna do! How do I get out of this?” character. It serves me well because then all I have to do is stand over him and say, “If you ever do that again, I’m gonna break your kneecaps.” It makes my job easier.

Odenkirk: The first thing I shot was the commercial, which was a lot like a Mr. Show moment. I mean, it was a loud commercial. Saul is being outrageous, and he’s playing a part of a loud lawyer, and he’s doing it purposefully and consciously. So that’s allowed to be an almost comic-level performance because it’s self-aware in its bigness.

Gould: We just loved writing for this character. And, he was very useful in the Walter White universe. He could explain to Walt anything we needed explained to Walt. He could introduce ideas like the disappearer. He could act as kind of a connector with Mike, and ultimately with Gus Fring. He was super handy. He was a skeleton key.

Odenkirk: I hadn’t seen much of Breaking Bad before I acted in it, only a few minutes on the plane. And Bryan anchored me. I mean, he really dialed me in.

Cranston: I think the first thing he said to me was, “I’ve never seen the show.” So it’s, “Well, OK. You’ve never seen the show. All right. Fair enough.” So I’m kind of giving him a lowdown on what it is.

Odenkirk and Cranston’s first scene together takes place in Saul’s office. Walter, who’s trying to keep a low profile by wearing aviator sunglasses and an Albuquerque Isotopes cap, is posing as the concerned uncle of Badger. Jesse Pinkman’s doofus buddy has been busted for dealing meth—and Walter wants to make sure he won’t squeal.

Cranston: I do remember that situation. I remember especially when Jesse Pinkman introduces me to him outside his cheesy office. He said, “You don’t want a criminal lawyer. You want a criminal lawyer.” And it’s, “Ah, yes, I get that…”

Odenkirk: He really helped me just know the show, just by sitting with him. Like I said, I hadn’t seen much of it. I knew it was a drama. I didn’t know how heavy it was. It was all about just tuning into Bryan, which might tell you a little something about my own approach to acting, which is to read the room as best I can.

Gould: Something Bob said to Vince and me when we started: “Don’t go easy on me. Make things in life as difficult as possible, put me in physically uncomfortable positions.”

Cranston: There was one scene early on in Breaking Bad when we kidnap him. And it was freezing that night and the wind was whipping and the cold wind just cuts under. I don’t know if it was single digits but it was close to it.

Odenkirk: What I loved about that scene was the outrageousness of the scenario and how we got to do it so realistically. We were out in the desert. We weren’t on some green screen. We were in the middle of the night. I was kneeling in front of a freshly dug grave. You know?

Gould: You can’t tell from the footage, but it was a full-fledged sandstorm. The actors were all getting sand up their noses, in the back of their throats.

Cranston: And we’re freezing. I’m holding a gun on him. My body’s shaking. I knew he was a part of the brethren. He is part of that ilk of people. It’s, “Look at what we get to do! Man, we’re out here freezing our asses off but this is how we make a living.” And I’m thinking, “Can we believe it?” And he was really excited about embracing the difficulty of it. The momentary uncomfortableness is accepted because the long-term gift of being storytellers for a living always prevails.

Odenkirk: It was one of the best production scenarios I’ve ever been a part of that wasn’t all cheated and faked and shorthanded, but actually played out, with this grand and very real feeling. Because it was real. And it all lent itself to this big and glorious drama that I was suddenly a part of.

Part 3: “The Worst Thing It Would Be Is a Failed Experiment.”

Walter White may not have survived Breaking Bad’s five-season run, but Saul Goodman did. After all, he’s a cockroach who can talk his way out of almost anything. As the show exploded in popularity during its later seasons, talk of a Saul spinoff began. First as a bit. Then seriously. Initially, Odenkirk wasn’t convinced it would work.

Gould: It was sort of a joke in the room. That, “Oh, this idea is too silly. We’ll do that on the Saul Goodman spinoff.” And I didn’t take it seriously at all because Breaking Bad already seemed like a gift from the gods. It seemed like hubris to even keep going or to think that might be real, but Vince really did want to do it. We both loved the character. All of us in the writers’ room loved the character. We all loved working with Bob.

Cranston: You felt what Bob was able to bring to it in Breaking Bad. There was a sense of history of a broken person. There wasn’t enough real estate to get into a deep background discovery of him in Breaking Bad. I think what Vince and Peter felt is that, “I think we have an iceberg situation and we’ve just tipped it. We’ve got a lot of real estate down below that hasn’t been discovered.”

Gould: We’d go for a walk through Burbank and often ended up getting a couple of beers and we’d just talk about what this thing could be. And we had so many ideas that did not end up working out. In fact, the first time we talked to AMC and Sony about it, we did say, “It’s a half hour.” I never felt completely comfortable making it a half hour for one simple reason, which is that true comedy writing is an art and a craft of its own. Those real comedy writers are a breed apart. They have a whole different skill set than I do. And I was concerned that if we went for the half hour, we’d be compared to the really funny half hours.

Odenkirk: Vince and Peter were after something different from Breaking Bad, but working in the same area.

Gould: The question was whether he was willing to do it, because Bob, he’s made no secret of the fact that he felt torn between his responsibilities as a father, and he’s a super, super involved father. It seemed like in his mind there was a conflict between the two and being away in Albuquerque so much. I think at the first lunch that we had to talk about it, I could tell that was a hitch for him.

Odenkirk: They were young, 13 and 15. And then the next six years, their dad was gone for half a year or more. But they grew to like visiting me in Albuquerque.

Gould: We would get kind of stop-and-go signals. We would meet him and feel that we were going to do it and then hear through the grapevine that maybe he wasn’t.

Odenkirk: My daughter asked me, “If it’s bad, how bad would it be?” And I said, “Well, it wouldn’t be bad. The worst thing it would be is a failed experiment.” Of course, I knew that if it was a failed experiment, there’d be a certain amount of people who, in retrospect—in relation to Breaking Bad—would consider it a big bomb.

But the truth is, I didn’t think it would be done in a sloppy way, without integrity or purpose. It may not work, but you’d have to give it some credit, I thought. That would be the worst it would be.

Gould: Once he was committed, we were thrilled.

Before shooting Better Call Saul, Odenkirk asked Cranston to meet. Here’s how Odenkirk described the scene in his new memoir, Comedy Comedy Comedy Drama: “We sat outside, because inside the coffee shop were ten people writing screenplays, and it’s not good to be around that if you’re a recognizable face.”

Odenkirk: Here I was going in to being the lead. And it wasn’t a character part, it wasn’t a small part. And I just needed to hear from Bryan something that sounded like work that I could do. I wanted to hear if there was any clue or trick. You know? And so I sat with him.

Cranston: I told him the story of when I was on Malcolm in the Middle. The star of the show, Frankie Muniz, was a boy. The next star was Jane Kaczmarek and she really didn’t want the mantle of leading the cast. So I saw there was a void and I thought, “Well, someone has to do this.” So I stepped in and kind of led the cast on cast meetings and issues that we dealt with.

Odenkirk: I think he thought I was having second thoughts or needing a spiritual boost. But really, I just wanted to hear something that sounded like hard work and just the meat of doing the job. And that’s what he gave me. He said, “Oh, you need to work all the time.”

Cranston: Other people would be, “Oh, you’re a star, you’re a star.” And I would immediately push back and deny it and say, “No, no, no, I’m just a working actor. No, no, no.” What I didn’t realize is that I was spending a lot of energy denying that position from outside sources that wanted to place that title onto me. And as I regale this story and I tell Bob this, I told him, “I realized that I was spending maybe more energy trying to push away that responsibility, that position in the industry. And then I just got in my own way.” So I stepped out of the way and just embraced it. And I said, “It’s there for you. I suggest you embrace it.”

Odenkirk: It put me at ease greatly. Look, I hadn’t gone to acting school. And Bryan had presumably done that and gone and been an actor his whole life. He laid out a day in your life and a weekend in your life, and how you hit the script, and you work. And you rehearse and you focus every chance you get. And that’s how you’re ready when you get on set. And I can do that.

Part 4: “Oh, Saul Goodman Wasn’t Even His Name.”

The first episode of Better Call Saul, which aired in February 2015, opens when Breaking Bad leaves off. Odenkirk’s character, a wanted accomplice of Walter White, is now hiding in Nebraska and working as a Cinnabon manager named Gene Takavic. Then the pilot flashes back. Aside from the occasional glimpse into the future, the series mostly focuses on the years before Saul Goodman is fully formed.

At the start, Saul is just Jimmy McGill, a reformed small-time Chicago con man who’s now a small-time Albuquerque lawyer. There’s plenty of crossover from the world of Breaking Bad. Fixer Mike Ehrmantraut and—eventually—drug lord Gus Fring both appear. There was also a new cast of characters, including Jimmy’s high-achieving older brother Chuck McGill and Jimmy’s romantic partner (and partner in crime) Kim Wexler. Odenkirk, his costars, and the writers enjoyed fleshing out Jimmy’s backstory.

Gould: We learned so much about Jimmy from watching Bob. And one of the things that you see is that Bob has this incredible energy and focus that’s unlike anything I’ve seen from anybody else.

Odenkirk: As it turns out, in that first season, I got hit with so much material and so much Saul Goodman chatter that I almost couldn’t do it. It was almost too much to even fit into a week. And at a certain point after about four or five weeks, I asked for extra time, and they did give it to me.

Banks: What I saw was this is a guy who is committed. And Bobby Odenkirk is smart. The amount of dialogue that was loaded on him. And he was losing his voice. I mean he was just nervous as a cat. And again, that’s my perspective. But my God did he rise to the occasion.

Gould: As we kept watching him, Jimmy being a failure didn’t seem as funny. He started to have a whole Willy Loman characteristic to him. There’s a pathos.

Rhea Seehorn (Kim Wexler): I got the first script and then watched Bob create this Arthur Miller or Glengarry Glen Ross character along with the scripts, obviously. But it just became this whole other thing that was beautiful to watch.

Cranston: I felt it in watching his performance in Breaking Bad, that he brought with it a wounded-bird mentality and sensibility to Saul Goodman. When I started watching Better Call Saul and realized, “Oh, Saul Goodman wasn’t even his name.” And there’s a whole history here and it’s, “That makes perfect sense.” And he’s always trying to live up to his star brother’s reputation and failing always.

Michael McKean (Chuck McGill): I had done All the Way with Bryan in Cambridge, and then later did it in New York. When we were doing the show in New York, I had heard that they were doing a prequel and it seemed like a very cool idea, because I loved Bob and this show and I love the character. So just right before we were about to step onto the stage one night, Bryan said, “Hey, you should, you should play his brother.” And I said, “Yeah, OK. I’ll make some calls or something.” And very shortly after that, I actually got a call from Vince and Peter.

Seehorn: When they announced they were going to do a spinoff, like many people, I was not sure what the tone would be, if it was going to be more broadly comedic, or is he going to be a sleazy guy getting up to antics constantly?

Gould: Bob and Rhea, you want to talk about chemistry. And we could see it.

Odenkirk: We felt that chemistry right from the first rehearsal reading she did.

Seehorn: It was the scene, I want to say Episode 3 of Season 1—it’s him calling me and waking me up in the middle of the night. And he’s trying to get information about the Kettleman case. And I very clearly have a boundary about it, like, “We’re not discussing cases.”

It seemed like there is an incredible closeness. Whether that is a very long friendship, or a used-to-be-dating, or a might-start-to-date. There’s something going on there.

Odenkirk: You never really know if that was a genuine connection, or if it just felt right that day and it’s going to be a problem down the line. But it did feel right that day.

Seehorn: He seemed a bit aloof for a second, but we were then told to go ahead and rehearse, just me and Bob, that everyone would leave the room and we’ll come back, “Why don’t you guys go through the scene a couple times just to feel comfortable with each other?” And when they left, I realized Bob was staring at his shoe. And one part of your brain wants to go like, “OK, clearly he doesn’t like me and this is going to go terribly. And this is going to be the worst chemistry read of my whole life.” But another part of me was like, “Or the only fact present right now is that Bob is looking at his shoe. So let’s start there.”

I said, “Hey, did your shoes come without the laces? Or did you take them out?” Because he had those Vans that don’t have laces on them, or maybe they were Sperry Top-Siders, I’m not sure. But there was no laces in them. And he looked up at me and he said, “They came this way. My wife got them for me at the shoe department,” and ended up telling me how he had been concerned.

He had never been the person that people have to do a chemistry read against, where their job and their hopes and dreams are pinned on reading with him and he’s precast. And he was very concerned about making sure he looked respectful, but not overdressed, but not too casual. And that his wife, Naomi, who’s amazing and lovely, had helped him. And it was this wonderful moment where he was so honest. But it took me being honest instead of in my head about what I thought he was thinking for us to get there. And then that’s where we started from, to read the scene, and it was great. I mean, I don’t know if I’ll ever duplicate it for the rest of my whole life.

Odenkirk: I’ve had some pretty amazing relationships in my life, my wife number one, Naomi. David Cross and I have worked together for years. And Rhea and I are on that same level of, we just fit together. Our priorities marry up, enough for us to spend that much time and sweat and focus on this thing that we share and not trip on each other and not feel frustrated or annoyed or claustrophobic with each other. It’s a lucky thing.

Gould: All we knew was that she was a lawyer who clearly had a connection with Jimmy. And I don’t think we got too deeply into it until Season 2. And my God, look where we are now. The show that we thought was a comedy about a goofy lawyer helping crazy clients turned out to be kind of a heartbreaking love story.

Jimmy and Kim’s partnership is the heart of Better Call Saul. But the key to what makes Jimmy tick is his relationship with his big brother. In the early ’90s, a heinous prank—look up “Chicago Sunroof” if you dare—nearly lands Jimmy in prison. Chuck, a high-powered New Mexico attorney, offers to get him out of trouble under one condition: Jimmy straightens out his life.

For a while, he does. Jimmy moves to Albuquerque. First he works in the mailroom at Chuck’s firm, then he earns a law degree. He also cares for his brother, who believes himself to have electromagnetic sensitivity. It doesn’t take long for the tension between them to rise.

McKean remembers Gilligan and Gould explaining Chuck’s condition to him.

McKean: They talked to me about the character and generally about his affliction. I said it sounded very interesting, I did a little research on it and learned it was a real thing, and that I had to treat it like a real thing, no matter what happened down the line. And they did me the great favor, by the way, of not telling me that I was a man with mental problems at all. This was really happening to me.

Gould: We could see pretty early on how Bob’s character got under Michael McKean’s character’s skin. And that was a little bit of a surprise. I think we thought that Chuck kind of tolerated Jimmy, and then McKean played the character with such pride. And Bob has this desperation about him to please his older brother, that we started writing to that, to that scorn and desperation and the constant running toward and running away that those two characters had.

McKean: When two siblings are that far apart and one of them is a big-deal achiever. … One of them gets out of high school at 14. Has his law shingle up when he is 23 years old. You are left in the dust more than you can imagine.

Odenkirk: I think it’s a deep well of hurt that anyone could have.

Late in the first season, Jimmy figures out that it’s Chuck, not Chuck’s partner Howard, that kept him from being hired at their firm. This leads to a confrontation where Chuck finally admits that he doesn’t think Jimmy is a real lawyer, especially compared to him.

McKean: The soul of the player, who is essentially what Jimmy is, and the achiever are just two different lives.

Odenkirk: It was an important scene to me, the most important scene in the first season, and really, an important scene for the whole series. It was the most I’d been asked to reach inside myself and connect with this person, this other character that I was playing. I don’t have those feelings towards my siblings. We’re friends, and we don’t have a rivalry that I could tell.

I had also been in this character’s skin enough at that point in the season that I felt for him, just for his own real experience of making a genuine effort to win his brother over and discovering that his brother was the one who doomed him. And I think that was almost enough to work with, just be Jimmy and think about how that would feel.

Part 5: “Well I’m Not Dead.”

As the final season of Better Call Saul approaches, it’s clear that Jimmy is the man that Chuck warned he’d become. After fully falling into a life of crime, can Saul Goodman be redeemed? Will Kim Wexler be OK? “It’s warranted, worrying about Kim,” Seehorn says. Whatever happens, one thing is certain: The experiment that Odenkirk was unsure about worked.

Odenkirk: I think we all were in the same place of like, “We’re going to make an honest effort. We’re going to push ourselves, but this may not work.” And if you’ve been in this business long enough, you should expect that to be the outcome. And so, I’m more surprised that it just plain worked and that enough people were able to tune in to the ways in which it’s not like Breaking Bad.

Gould: The first thing he said to us at lunch, Vince and me, he said, “I don’t think I need a full trailer. I think I can be in a two-banger.” And, by dint of an example, he’s not taking all his privileges. He’s there for the work.

Seehorn: He said, “I talked to Bryan and he said, ‘If you have one, then other people should have one. And every time you add another trailer, add 15 minutes to a company move. And then tell me how much you wish you could get home in time to get enough sleep.’” And I was like, “Oh, that’s so good.”

Ed Begley Jr. (Clifford Main): He was a good captain whenever we needed him to be, or he needed to be, but he was very much an ensemble player, too. He could carry it easily on the broad shoulders of his talent. We looked at him for guidance every week.

Gould: He immediately made it his business to befriend and open the door to actors who are only there for a day or for a week, or for a small role. It’s Peter Diseth who plays DDA Oakley, who appeared in the second episode and has been one of our favorites all the way through, as a local Albuquerque actor. There was a day where he couldn’t go and rehearse with Bob because he had to babysit his child. And so Bob came to Peter’s house to rehearse.

Burr: There was a real warmth with him and a humbleness where he would talk to me about stand-up as if I was as good as him, way back in the day. I was like, “Is this guy really asking me about my process?” Because I was just like, “There’s nothing in my act that can touch what you’re doing.”

McKean: I think that he really liked being in a hit, and we all do and we all did, but I think there was something about, “Oh, it not only works, but other people think it does too, and we got a good one here.”

Seehorn: And there was one point where the late, incredibly great, David Carr came to do his last media piece that he did, on Better Call Saul. He had rolled up an office chair and was talking to Michael and Bob, and these guys are trading stories, but also a very real conversation. And Michael, like Bob, he’s never looking for a place to do a bit. He’s never looking to one-up somebody. They were having this conversation that was comparing like eight books of complete different genres from different time periods. It was like, insane, the amount of allusions and references that were going on. And I’m walking by and I can hear them, and I’m trying to listen. They’re like, “Rhea roll a chair up, roll a chair up.”

Banks: I love the stuff we did in the desert. You’re doing a scene, you’re both exhausted, you’re both sweating, and it really is hot. And up comes a dog out of nowhere. A mangy dog. And she comes up and she gets under the bush with us in the shade. And immediately things stop and they bring water down from the trucks. I like the scene because it’s just before we’re gonna snipe the bad guys and the truck does all the turns and the rolls and that kind of stuff.

Bobby took that dog—this is my affection for Bobby—he took that dog home. The dog was pregnant and out pops eight puppies. And homes are found for all of them. So that moment, that day, I promise you, is far and away—because there were extraneous things going on—it was my favorite scene.

Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul led to more juicy dramatic roles for Odenkirk, who in 2021 starred in his first action movie: Nobody. But last year turned out to be extraordinarily difficult for him. In July, on the set of Better Call Saul, he collapsed. His costars, Patrick Fabian and Rhea Seehorn, watched him fall and called for a medic. He’d had a heart attack. Odenkirk told The New York Times that it took three defibrillator shocks to bring his heart back into rhythm. An ambulance brought him to an Albuquerque hospital, where he had a procedure to clear plaque in his heart. He spent a week recovering from the event; an event he doesn’t remember.

Odenkirk: It’s a complete blank for me. It’s like I fell through a time hole and came up about a week and a half later kind of groggy, but pretty much myself, with no memory of any of it and a strange, chipper attitude that was like, “Let’s go back to work. Hey, why’s everybody so down?” “Because you almost died.” “Did I? Oh, OK. Well I’m not dead. I’m fine. Let’s go to work. Let’s go shoot the show.”

Seehorn: If he had gone to his trailer, we would have a different outcome, but he chose to stay on set and was hanging with Patrick and I. Thank God.

Gould: I know that it was really upsetting and just to everyone on the crew, the whole group was—I’m trying to find the right word—just upset, shaken.

Cranston: We didn’t know to what degree he was in trouble and then you worry about him. God, he’s in the hospital and I’m calling him. Then you rely on the network of people who you know are friends of friends and saying, “Have you heard from Bob?”

Banks: And then you wait. And you wait to hear, good or bad, what’s gonna go on.

McKean: I’m saying, “Oh God, what’s going on?” I tried to get in touch with, I guess Rhea, and there was stuff that came down the pipeline from Peter and Vince and saying, “He’s resting, it’s all good.”

Odenkirk: I had to make an effort to hear about what happened, think about what happened, picture my friends all gathered around me, picture what that day was like, what my wife went through. The surreal part was everyone’s tenderness and kindness towards me. And it’s because they were traumatized, not me.

Gould: When we found out that he was going to be OK, that was a glorious day.

Seehorn: If you’ve ever lost someone, and most of us have, to come back the next day and go, “Never mind, you can have a whole second chance,” is one of the most amazing things you could ever experience. There’s no way to even short-change what a gift that feels like, for sure. He is a gift in my life anyway. I’ll try not to cry, and I’m very close with him and his family, and it was traumatic. And thank God he didn’t leave set.

Cranston: For all of us to really be able to embrace him and say, “I’m glad you’re OK. You dodged a bullet and by extension, so did we.”

Begley: The outpouring afterwards, that’s the It’s a Wonderful Life Jimmy Stewart moment for him. How loved he was, and what he means to people, that was just great for him to see.

McKean: Maybe it’s just me, but once the initial crisis had passed, I knew he was going to be better than ever, and just he’s one of those guys. He’s very responsible, really takes care of himself. He’s figured out what’s to be done.

Gould: When we found out that he was actually going to come back, I think it was a little worrying, because you always worry. Is he coming back too soon? And knowing Bob, when I talked to him and he was in recovery, he was calling me and saying, “Send me scripts. I got time to read.” And I hear in the background Naomi, his wife saying, “No, they told you not to read. You can’t sit and read scripts. You’re supposed to be quiet for a little while.” So he was raring to go maybe before he should have been.

Odenkirk: We all felt close to each other, after six years of making this show. We spent 14 hours a day together, maybe more. We get very exhausted together. We celebrate each other. We become very, very close in the crucible of making a show like Better Call Saul.

Gould: The first shot you see of him this season actually was shot after and it cuts seamlessly. And what was wonderful was to see that he was absolutely himself. He had all his energy, he had all his goodwill. I’d say that he’s always been a generous, kind person and a great collaborator, but I think there’s an extra measure of generosity and helpfulness and openness to him now.

Odenkirk: I think the impact on my family and my crew and castmates was so big that it has affected me in retrospect, in like a weird kind of bounce back. That’s been a bigger effect than the actual heart attack. And then the kindness that I got from people on social media and just from strangers and fans, that’s inexplicable to me. I don’t entirely grasp why. I’m thankful for it, and I’m in awe of it. And I don’t know what to do except to try to live up to it.

I don’t think I’ve been the kindest, most generous person. And so I got this outpouring of love and I had to ask, “I don’t deserve this—have they got the wrong Bob Odenkirk yet again?”

Interviews have been edited and condensed.