Following a two-year, pandemic-induced hiatus, the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival will return this weekend for its 21st edition, with headliners Harry Styles, Billie Eilish, the Weeknd and Swedish House Mafia. In anticipation, we’re looking at the event’s history and the festival-industry landscape on Thursday and Friday. And check back next week for our coverage of Coachella 2022.

The first person I approached to talk about the placement of performers on the posters for musical festivals—those elaborate bills that list artists in descending font-size order from huge headliners to supporting acts so small it takes a microscope to see them—offered a terse and unpromising response. “Ha, what a terrible topic!” she said.

As a music industry veteran who’s worked in all kinds of capacities, from marketing and promotion to artist programming and event management, she bears the scars of repeated poster battles. And the best way to approach placement, she said, is to list acts alphabetically: “Otherwise you are dealing with ego, who is bigger, who thinks they are bigger, who sells more tickets, who can yell louder, who can threaten easier, all that crap.” All in all, she said, the subject makes her feel like kicking a puppy, which may be why she preferred not to be named. (To be clear, she likes puppies and would normally not kick them.)

The alphabetical answer to sidestepping poster drama could be catching on, but most festivals—including this weekend’s Coachella, where posters have followed the same format for almost 20 years—still employ some version of the time-honored model: A musical hierarchy conveyed via an avalanche of text that ranges from gigantic to tiny, denoting the drawing powers of the performers. The making of a poster may be opaque, but the poster itself is refreshingly and intriguingly transparent: It puts performers in their places and then specifies those places for the public to see. In their revealing and occasionally confounding way, posters elevate some artists and cut others down to size, making them a medium that combines the cachet of world-famous celebrities with the jockeying for social status of a high-school cafeteria.

Stereogum senior editor (and Ringer contributor) Tom Breihan, a poster scholar whose annual exegeses of Coachella bills are required reading on the (purportedly terrible) topic, sums up the festival poster’s appeal this way: “In most situations, it’s a little hard to tell which acts are more popular than other acts, and most mid-level bands or artists can start to feel interchangeable. But when you see all those artists’ names arranged on a poster, you get a cold, clear vision of which artists the festival bookers value the most. … People have put in real work to figure out which acts are the biggest draws, and something like the Coachella poster spells out exactly what they’ve decided.”

Of course, posters aren’t pure distillations of promoters’ rankings; they’re the end result of grueling negotiations. Poster politics can get contentious, and most festivals declined our requests to address how they handle placement. Yet several festival bookers and artist reps were willing to go on the record to explain how the process works. The delicate dance they described sits at the stressful intersections of art and commerce, feel and data, and diktats and diplomacy. And although there’s a loose script that guides discussions, it doesn’t always stop feelings from getting hurt or help promoters and artists find common ground. As musicians earn more of their revenue from touring and the proliferation of festivals makes mass events a more important piece of the live-performance pie, billing matters more than ever. “It seems to be much more important to artists these days than it used to be,” says Bryan Benson, lead booker for Live Nation Entertainment, which promotes thousands of concerts and festivals per year. He adds, “To some artists, it might be the most important.”

Last month, rapper Joyner Lucas became the latest in a long line of performers to protest placement on a festival poster—in his case, Chicago’s long-running Lollapalooza, one of the biggest blue-chippers in Live Nation’s festival portfolio. Lucas was listed on the 10th line of the Lollapalooza poster—the first line rendered in the poster’s smallest text. That put him nine lines and three font sizes below Machine Gun Kelly, whose headliner status prompted Lucas to tweet “Smh how sway?” The rapper reserved most of his ire for Lollapalooza’s promoters, whom he said “put my name in some tiny ass letter like i ain’t me” while other artists who “ain’t even on my level or doing my numbers is getting put in BIG LETTERS.” Lucas’s gripe echoed 2 Chainz’s objection to Governors Ball relegating him to the eighth line of its poster in 2018, though they both could learn from Janet Jackson, who in 2019 took matters into her own hands and tweeted a rearranged version of a Glastonbury poster—possibly sanctioned or created by the festival at her behest—in which she was transformed from fifth headliner to first.

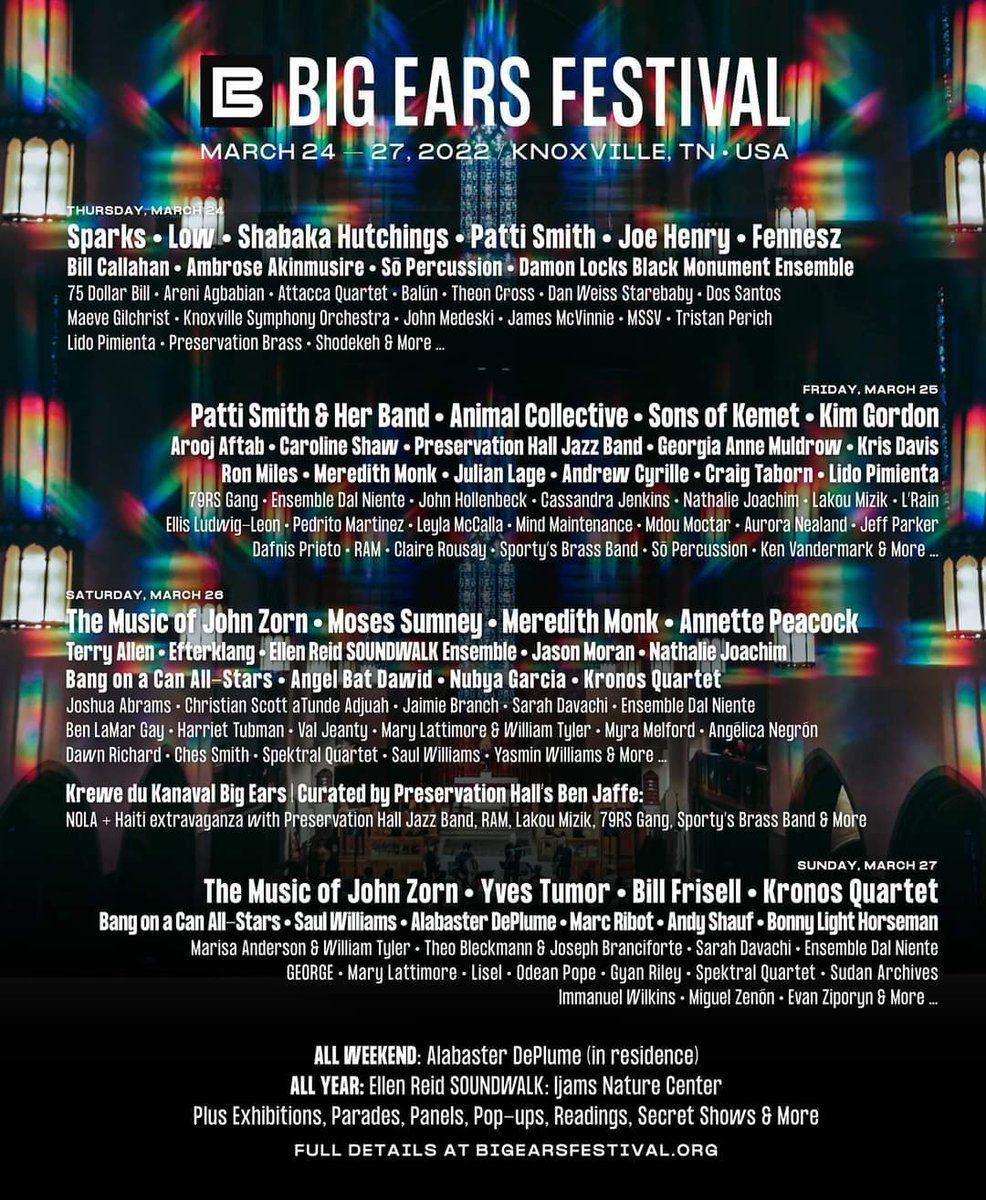

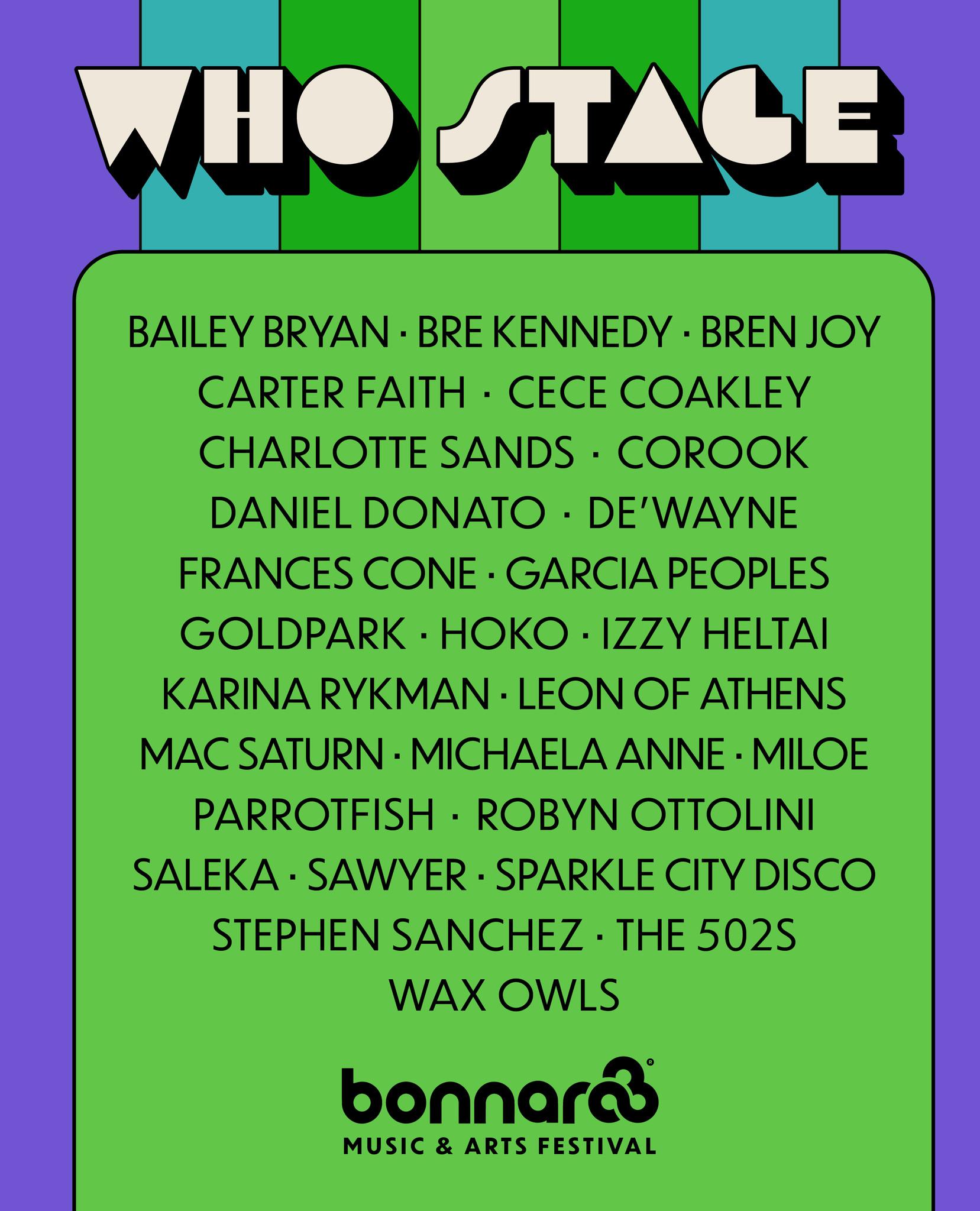

Like Kanye, Lucas later walked back his “how sway?,” memory-holing his string of Twitter complaints, posting an apology, then deleting the apology too. But artists who make poster placement a priority aren’t uncommon, and neither are ruffled feathers among those who don’t end up where they want. “Everyone wants to be basically portrayed in a way that’s commensurate with their profile as an artist,” says Ashley Capps, who founded music promotion company AC Entertainment and developed the festivals Bonnaroo and Big Ears, the latter of which he continues to program. However, he notes, it’s not always a given how that profile will translate to posters: “Sometimes it’s really obvious, and often it’s a little bit of a judgment call and everybody doesn’t necessarily see it the same way.”

As one would expect, there’s a close correlation between appearance fees and poster placement, though Benson says it’s “not a hard-and-fast rule” that the higher the payment, the higher the poster position (or vice versa).

From a promoter’s perspective, the poster is important because it’s one of the festival’s most potent marketing tools and differentiators from competing festivals, and the order of acts is crucial because it produces the poster’s first impression. “Your biggest artists and biggest ticket sellers, biggest names, they’re generally going to be up top in a larger font because it is a marketing asset to go out and convert ticket sales,” says Lee Anderson, executive vice president and managing executive for music at talent agency Wasserman Music. But “biggest” is sometimes up for debate, and “that’s where the agents and the buyers get into it,” says Anderson, who estimates that this back-and-forth represents “probably 20 percent of what I do for a living.” Among the many giveaways in Netflix’s 2019 documentary Fyre that the Fyre Festival was headed for disaster was inexperienced Fyre Media booker Samuel Krost’s comment to an agent: “I mean, it’s just a font size.” It’s rarely just a font size; even kerning can be a bone of contention.

Benson says promoters’ preferences reflect “mostly feel” as opposed to advanced poster-placement sabermetrics, a sentiment also expressed by Phil Pirrone, founder and creative director of the decade-old Desert Daze festival based in Joshua Tree, California. “The data has to be sifted,” Pirrone says. “There are so many different factors that go into play that you’ve just gotta use your gut at the end of the day. Not blindly—that’s what the data’s there for—but you can’t just rely on the data alone.”

Artists’ teams will make stats-based appeals when they think the numbers warrant improved positioning. Information on monthly streams can be a differentiator among mid-poster acts. Anderson says he’ll also send data on local, national, or global ticket sales, social media following and engagement, and Google Trends graphs that compare multiple artists’ search patterns. Tools such as Pollstar and Chartmetric can aggregate much of that data. “We’re not hardheaded on this stuff,” Benson says. “We will take what’s presented and consider it. And if there is compelling information that does justify some adjustments, we will do that.”

That said, certain performers break the metrics. “Some bands, their fans are listening on vinyl,” Pirrone says. Talent manager and former concert promoter Kevin Morrow, the founder and CEO of Steel Wool Entertainment, cites Dave Matthews and Jimmy Buffett as examples of artists who don’t have huge sales or streaming figures but do draw rabid crowds. And then there are artists like Frank Ocean, who aren’t prolific but whose sporadic output attracts a ton of eyes and ears. “What’s hard to quantify but is often debated is cultural relevance,” Anderson says. “What does this person mean? Maybe they’re quiet on the socials. Maybe they only put one song out a year so their streams aren’t as high, and they very rarely play a concert so you can’t point to it, but they’re incredibly significant.”

There’s also an element of handpicked curation that raw data would have a hard time replicating. “We’re trying to tell a story with the lineup,” Pirrone says. “We’re not just trying to do, ‘Here’s what the algorithm spit out!’”

In 2017, for instance, Pirrone booked Iggy Pop, Terry Riley, and John Cale to play the same day at Desert Daze; both Pop and Riley are former collaborators of Cale’s. “The order that they were all put in was thoughtful and methodical,” Pirrone continues, adding, “We want it to be more than just a collection of artists that don’t mean anything to each other, in whatever order the ‘best new music’ section at Target dictates. We want to do it a little differently, if the agents will let us.”

The makeup of the lineup and the composition of the poster likely matter more to smaller festivals like Desert Daze than they do to behemoths like Coachella and Lollapalooza, which have histories of recruiting top talents and built-in audiences that make pilgrimage every year. “If you’re Glastonbury, or if you’re Coachella, to be honest, they could go on sale and probably sell out without even listing the artists,” Morrow says. (In fact, they have.) But even in the cases of less-established events, “the positioning impacts the festival a lot less than it impacts the particular artist who might be affected in their growth or where they are in the market,” Anderson says. Benson understands why it can become a sticking point: “If an artist is presented at a certain spot on the poster to others in our business, it says, ‘This is our value to this show.’”

The degree to which agents will fight for better billing depends on the act. Benson says “not as many [artists] as you would think” are sticklers about the way posters present them, and that there are only “a few that are really vocal and really passionate about it,” which Anderson corroborates. “Some people place a lot of value on their positioning, some people don’t,” he says. “There are some scenarios as an agent when it’s really important to argue for where your client is, because they’re on the rise. … If I accept a certain slot or billing positioning, I’ve set precedent. Now when you talk to festival A, B, C, D, E, they might reference this one festival poster to [say], ‘Well, I can’t give you a bigger slot or I can’t put you on the poster here because you’ve already taken this.’”

Morrow recounts some pre-COVID, font-size haggling he did with Lollapalooza when he represented Anderson .Paak and Hayley Kiyoko. “I knew from the offer that [.Paak] was in their B-tier, and I was fighting for him to be an A-tier artist,” Morrow says, recalling that the festival was basing its evaluation on .Paak’s ticket sales from before his second album, Malibu, blowing up. “I wasn’t saying either one of them had to be above another artist,” he adds. “I was just saying I wanted them in the A-tier.” Morrow went 1-for-2: The negotiations worked in .Paak’s case, but not in Kiyoko’s.

For the most part, promoters aren’t trying to snub any acts they’ve invited. “I’m not saying we ever get it quite perfect, but we do our best,” Capps says. “It’s very important to me as a promoter and as a fan. I want to see artists treated with the proper respect that they deserve given their stature of accomplishments in the business.” However, festival bookers may have to balance several factors that artists aren’t aware of. For a multidisciplinary festival like Bonnaroo or Big Ears, for instance, the top of the poster is designed to showcase the variety of genres represented. “If somebody is reading it as it’s written across each line, we want them to understand that ‘Oh, there is a lot of hip-hop and rock and indie and folk offerings on the show, not just one of this one thing,’” Benson says. And Anderson adds that “As we all strive for more diversity and equality in the world, I think that promoters are making a concerted effort to try to make sure that their posters reflect that,” though that’s less a matter of bumping performers up the poster than it is of making a concerted effort to book them in the first place.

Then there are cases, Capps says, where “it becomes really complicated because we’ve got major artists in a certain genre or a certain field who are not household names by any stretch of the imagination. Your average person has never heard of them, but nevertheless they may be a superstar in their field.” Something along those lines occurred with an unspecified artist who recently played Big Ears. “They certainly have far more listeners on a monthly basis, say on Spotify, than most of the artists that were playing our festival,” Capps says. “But nevertheless, they were also basically unknown to most of the audience that attends our festival. So that was an interesting discussion. And we ultimately had to agree not to agree.”

A similar scenario can occur when an artist has a sizable following in a region other than the one where the festival takes place. The potential for popularity to be lost in transportation was probably to blame in 2019, when Nigerian singer and rapper Burna Boy put Coachella on blast by writing on Instagram, “I don’t appreciate the way my name is written so small on your bill. I am an African giant and will not be reduced to whatever that tiny writing means.”

Other times, bookers have to lick the tips of their fingers, stick them in the air, and try to gauge which way the wind of culture is blowing an artist who may be moving into or out of the spotlight. Capps says, “Sometimes you’re weighing things like an artist who has a 30- or 40-year career against an artist who has one huge hit record,” which puts the festival in the uncomfortable position of deciding which would move more tickets in a top poster spot, a legacy act with a stale-but-legendary discography or an upstart with a lone, zeitgeisty release. Up-and-comers’ egos aren’t the only ones that get dinged; old-timers may be less likely to take their complaints to social media, but it can still sting to slip out of poster territory that an act has counted on claiming for decades.

Pirrone leans toward career record over recency bias; in 2016, the festival featured Television as its second-billed band. “We don’t just take into consideration who’s hot right this second, whereas I think some other festivals maybe play into those politics a bit more,” Pirrone says. “We try to take into consideration some legacy as well. Within reason, of course, because if you’re talking about one act that sells 300 tickets versus an act that sells 3,000, it’s pretty cut and dried who gets higher billing.”

Pirrone’s respect for his elders isn’t always conducive to smooth resolutions. “There’s always a couple tough, tricky conversations every year,” he says. We usually get threatened at least once or twice—‘If you don’t do X, Y, Z, I’m pulling my artist off.’” One year, there was a standoff in which both of Desert Daze’s headliners—one legacy act and one newer act that was selling more tickets at the time—told Pirrone they would drop off unless they got top billing. “I was just like, ‘I can’t lose both of you. I can’t lose either of you! So let’s try to figure this out.’”

After a few days of dead-end discussions, the crisis was resolved when the agent for the legacy act made the case that the unique milieu of Desert Daze—a focal point of a dedicated, psychedelic-rock community—merited higher placement for an enduring artist that was integral to that scene. “That was the magic word,” Pirrone says. “Everyone got it. Everyone was like, ‘OK, you acknowledged that our artist is bigger, that if this was Lollapalooza or something we would be billed above you. But yeah, you’re right. Because of who you are and what your relevance and significance is to the scene, the community of Desert Daze, you have a point.’”

Although negotiations over poster positioning can be testy at times, Benson says they’re “very compressed.” Anderson notes that headliners, some of whom get booked more than a year in advance for certain events, may demand even then to top the bill, but the font fates of lower-tier artists are generally decided much later. “We do tend to let everybody know what their positioning is going to be in advance,” Benson says. “That way, if there are any hot-button issues, we can address them before we publicize the poster.” To avoid lineup leaks, though, Live Nation avoids passing around provisional posters for feedback long before the big unveiling. Benson continues, “A lot of times we’re finishing the lineup within a week or two of announcing. … Our goal is [that] whenever we do press ‘go’ and put it out there publicly, that that’s the final product.” Anderson says it’s common for agencies to receive watermarked mockups of unfinalized posters, which often get tweaked multiple times in the week leading up to release. But posters sometimes change after they’re announced. That can be because unconfirmed acts were added, but Anderson says it also sometimes reflects the loss of “a few artists that have come off over billing.”

Increasingly, reps for even non-megastar artists will communicate their poster preference upfront rather than waiting to see a draft months later. Sometimes, Benson says, “we’ll address it as best we can in the process of confirming the act to perform in the initial discussions. And sometimes the agent or manager will do a good job of saying, ‘Look, the billing is going to be really important to us,’ so that we’ll know going in that for this particular artist, this will be an important part of the negotiation.” In those cases, the poster is just another initial bargaining point, along with the fee, the stage and time slot, and so on. But it’s difficult for the booker to commit to a layout before the full festival roster is confirmed.

Most of the time, the parties start out on the same page (or the same poster) or eventually reach an understanding. But it’s not unheard of for an artist to walk away when a compromise can’t be struck. “In some scenarios it could be a deal killer for the artist and their team,” Anderson says. “They might say, ‘We are unwilling to do this. We would love to play. The money seems great. The slot seems great. But we can’t have this precedent where that is where we are perceived to be in the pecking order of the business right now.’” For Anderson, that’s the worst-case outcome. “I try not to ever let anything die over billing,” he says, adding, “If I find it’s egregious, it gets to the point of you’re not even debating anymore. But I think if you are close, the advantages of playing to that large audience and building your fan base and giving that experience far outweighs where you are in the poster.” As Morrow puts it, “[With] most of those giant festivals, most managers are just glad to get their bands on the show.”

It’s not the end of the world when talks break down. It may not even be the end of a professional relationship. “If you don’t come to terms, there’s no hard feelings and all that’s water under the bridge, as far as I’m concerned,” Benson says. “And I’m sure there have been instances where we’ve had issues with billing and it didn’t work out, and that artist didn’t perform, and then we booked them again next year on something else.”

Even so, one side or the other may attempt to preempt the discussion and forestall any potential for bad blood. On the artist’s side, Capps says, “Many times these days, I think it’s just spelled out from the very beginning: ‘This is how we expect to be billed.’” The makers of some posters play hardball, too. “Now some festivals say, ‘We are not even having the conversation,’” Anderson says. “‘We are going to choose the billing, that’s it.’ And at that point, as an agent, you either say, ‘OK, I’m going to trust you, and I hope I’m in a good place’ … or some artists and agents say, ‘We are unwilling to accept that. We need to know exactly where we are billed on the poster or we won’t confirm the deal.’”

The other option for promoters who want to steer clear of pre-announcement squabbling and post-announcement Twitter venting is to break the wheel by eschewing the traditional poster structure. Anderson says that as poster placement “became a bigger deal and a much bigger fight, and not just at the headline level but low down the poster,” promoters were overwhelmed. “If you are a talent buyer of a major festival, you’ve got like 90 arguments going on,” he says. “All you’re doing is fielding calls about this agent who’s on the 14th line wants to be one slot over. It got out of control.” One solution has been switching to a design that makes the hierarchy less clear, which “saves a lot of people a lot of headaches” and makes people “put their knives down a little bit more than they used to.”

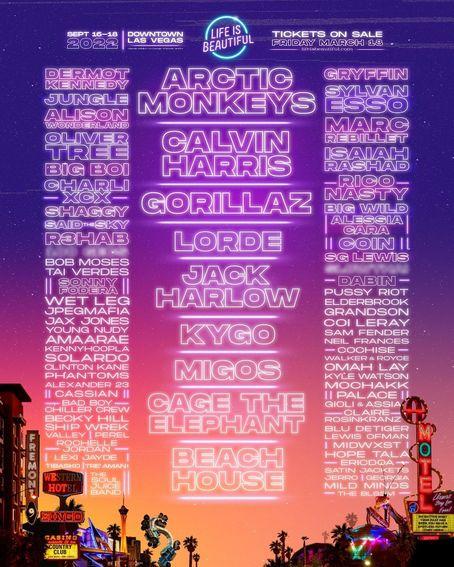

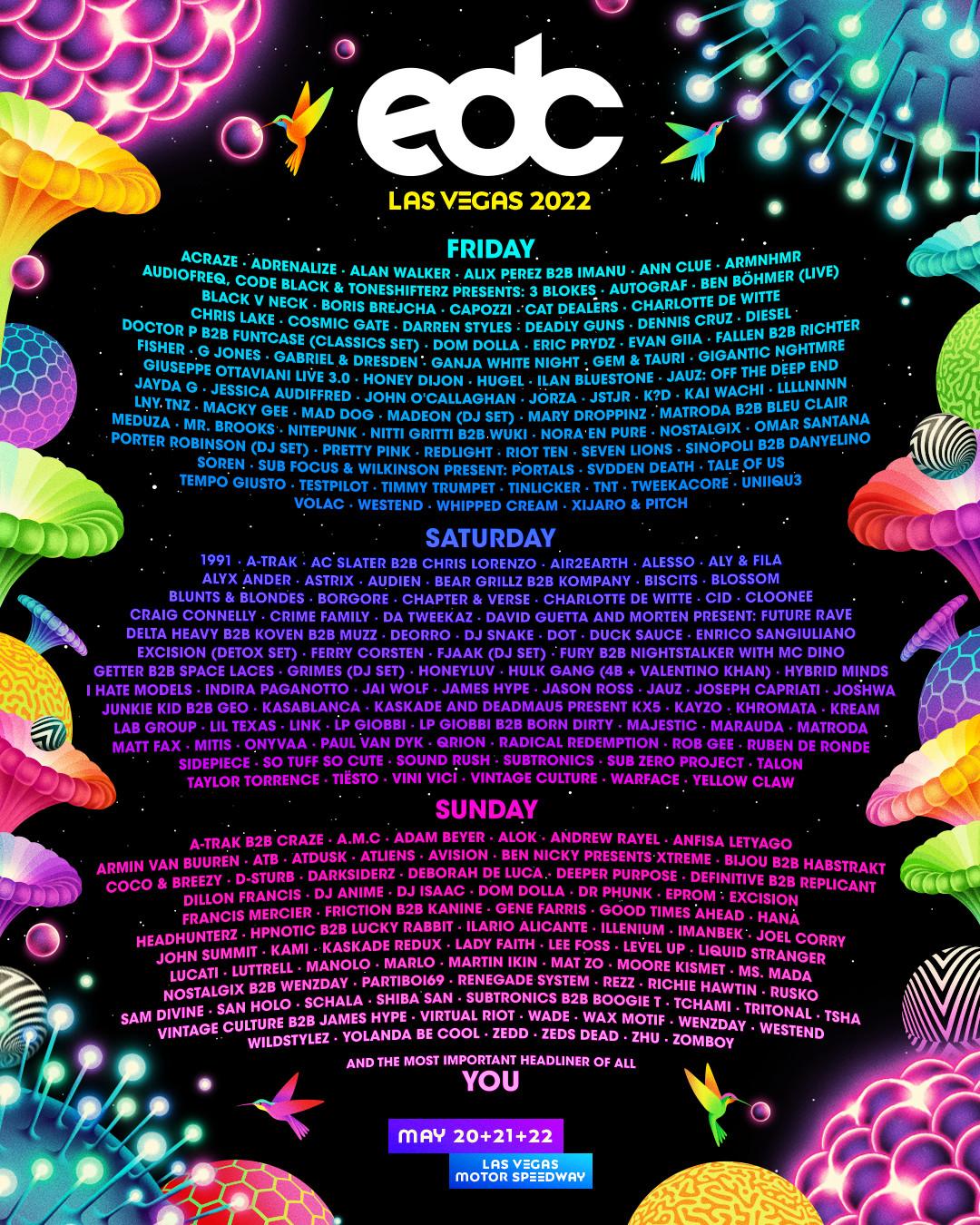

That may mean splitting the poster by day or stage so that the headliners won’t have to dicker with each other about which one gets the top top billing. It may mean getting creative with colors, columns, and tiers and ordering artists in ways that “don’t make it as clear as to who is bigger than who,” like the posters for the Life is Beautiful festival in Las Vegas (or, to a lesser extent, Austin City Limits, which lists headliners on the left side of the poster). And yes, it may even mean embracing alphabetical order, à la several festivals organized and promoted by Insomniac.

“They’re like, ‘We’re done with this.’” Anderson says. “‘We’re going to have great talent. It’s about the experience. We’re not having these arguments anymore.’” Pirrone sympathizes with (and even envies) that approach. “I understand why festivals have reverted to alphabetical order,” he says. “It’s hard to make everybody happy. That’s my goal. If I can make every artist on this festival happy with their billing, then great, [but] it’s an impossible task.”

This year, Glastonbury went full alphabetical with full font-size equality below its four headliners, relying on differences in color to make each act stand out. That change from the venerable festival’s pre-pandemic poster layouts didn’t go unnoticed by promoters like Benson, who says, “It certainly caught my eye that they did that. … I like it a lot, actually. And who knows? Maybe it’ll end up being an inspiration.” (Bonnaroo does list the acts on one of its smaller stages in alphabetical order.)

But not everyone is an alphabetical believer, especially for festivals with a larger array of acts. “From a design perspective, having 150 or more artists listed the same font size is strikingly unattractive, if you ask me,” Capps says. “I think it does a disservice to the event. It’s hard for anything to stand out.” Pirrone says he’s been tempted to go alphabetical, but thus far he’s come to the same conclusion as Capps. “It takes reading the whole thing to see the big ‘Wow’ moment,” he says. “I just get uninterested. I’m reading through this novel of band names, and I’m like, ‘I don’t really care.’”

Whatever the future of the festival poster, the progress has grown more forgiving in one vital way—if not for the musical artists who appear on the posters, then at least for the visual artists who design the damn things. “Before Photoshop, I had to pen it in on the poster,” says artist (and my cousin) Jason Rizzi, who’s produced posters for events such as the High Sierra Music Festival. “That made it a bigger hassle to add or move around the acts.” Poster disputes and last-second lineup adjustments may be more common than ever, but at least the late scratches don’t send designers back to the drawing board.