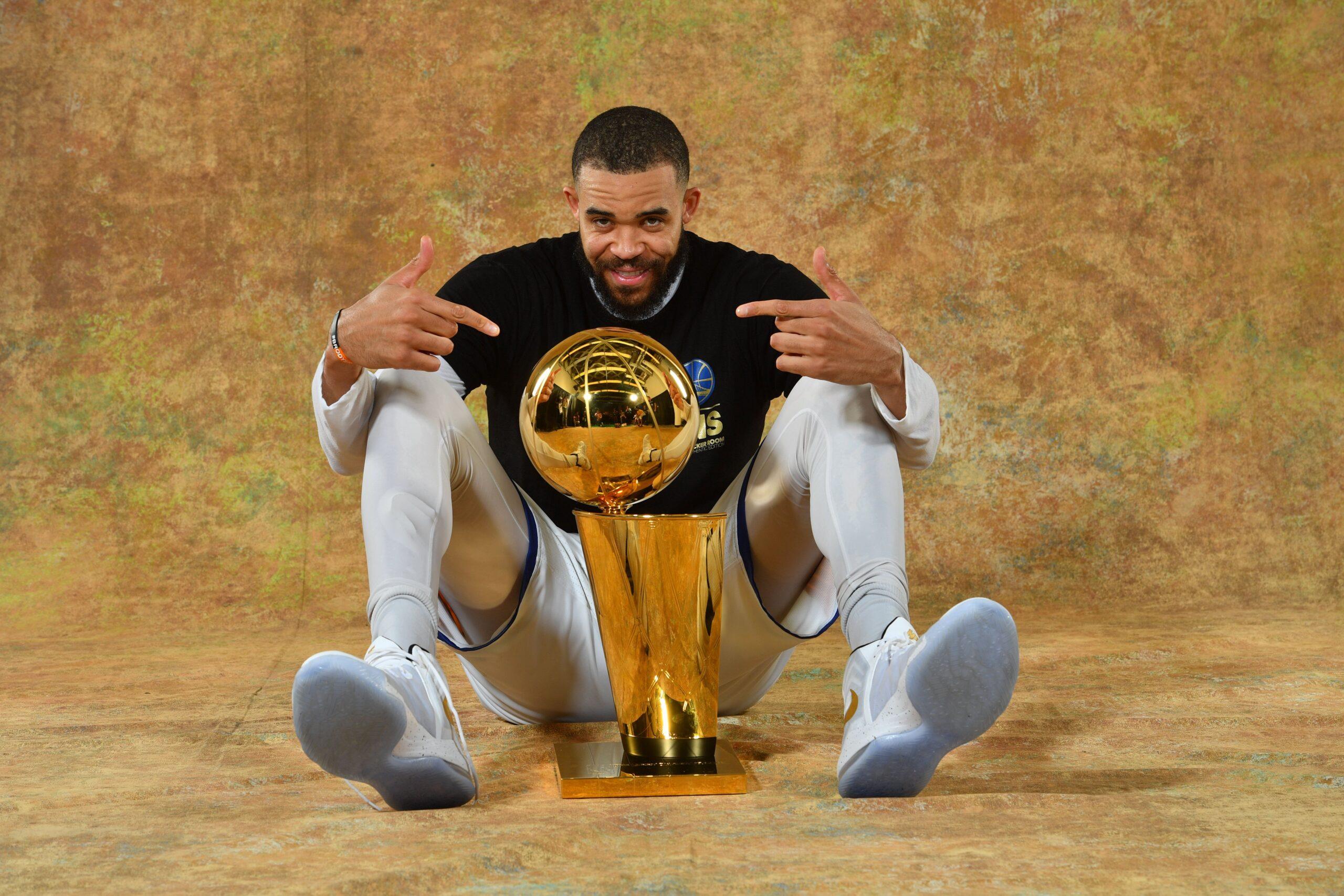

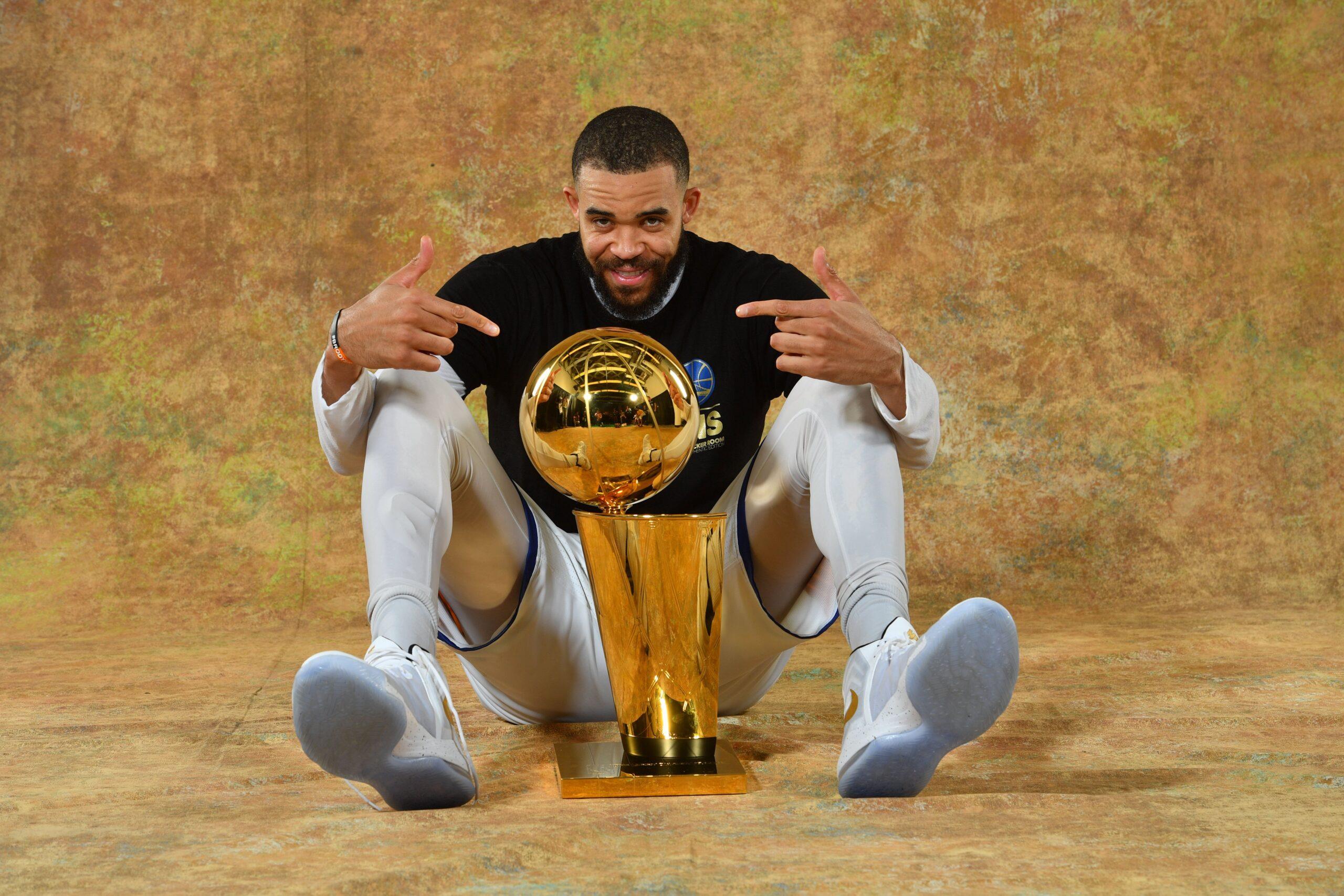

JaVale McGee is many things. A three-time NBA champion and Olympic gold medalist, a spring-loaded giant with the size to contest NBA bigs and the quickness to stick with guards. A serial startup investor and entrepreneur, someone Warriors forward Andre Iguodala calls “one of the smartest people I know.” But right now he’s sitting on a couch in the lounge of a Salt Lake City hotel, sipping a Sprite and talking about the one identity that always seems to follow him, no matter how many games or series or rings he wins: guy who used to get made fun of on TV.

For a few years, Shaquille O’Neal took a special delight in showing clips of McGee on Shaqtin’ a Fool, the popular blooper segment of the Inside the NBA broadcast. He was, perhaps even more than O’Neal, the segment’s biggest star. He missed dunks and tripped on breaks and did it all with an earnest passion, like a sprinter running smack into a brick wall. Shaq showed his clips and made his jokes, and soon the jokes leapt from TV to Twitter, and from Twitter into locker rooms and executive offices around the NBA. McGee says that because of portrayals like this, “coaches, GMs, and even players thought that I’m this dumbass.”

After nearly falling out of the NBA, McGee resuscitated his career by focusing on protecting the rim and dunking every lob that came his way. But he worried, at times, that the reputation he’d developed on TV and online could jeopardize his ability to stay in the league. “What did I do to make you think I’m dumb?” McGee says, pointing out that his GPA was above 4.0 in high school. “Or what did I do where you think I’m not a good teammate? Or that I’m a cancer in the locker room? There were a lot of clouds around me, and it came from seeing this on TV.”

Perhaps more than ever, NBA players are now talking back to their media critics. Kevin Durant spent a few days last month going at it with Charles Barkley. Draymond Green took to his own podcast to clap back against ESPN’s Chris “Mad Dog” Russo. It’s all great theater for fans, the moments between the moments that make up the actual games. But the media narratives around players don’t only impact how they’re viewed by fans. “Honestly,” says Suns point guard Chris Paul, “even as a player, if you don’t really know somebody, you just know them through what you see on television, you know? So if all you’re ever seeing is their bloopers, or hearing jokes about them on Shaqtin’ a Fool or whatever, it affects you.”

“What did I do to make you think I’m dumb?” says McGee, whose GPA was above 4.0 in high school. “What did I do where you think I’m not a good teammate? Or that I’m a cancer in the locker room?”

For years, I’ve wanted to write about McGee, to ask him what it was like for a flesh-and-blood human to be turned into a meme. The first time I asked, back in 2016, I was told McGee wouldn’t talk about it. While working on this story, someone close to him expressed hesitation, mentioning that when The Ringer covered Warriors media day after his signing, they made light of the online mockery he dealt with. I expressed shock and regret that one of my colleagues had done this, only to realize, some time later, that I was the one who wrote it.

But when I finally sit down with McGee in Utah, he brings up the mockery he experienced from media and fans, unprompted. He has one of the most singular career trajectories in the NBA. He’s a player once known largely for committing blunders on losing teams, and he now has a real chance to win his fourth championship with three different teams, something only three players in the history of the sport have ever done. “My goal these last few years,” McGee says, “has been, ‘I’m gonna build my reputation back up. I’m gonna build my foundation back up. Honestly? I’m gonna get as many accolades as possible.’” He shrugs his shoulders. “Because now? You can’t say a damn thing to me. I worked my fucking ass off to get where the fuck I am.”

The Suns are McGee’s eighth team in 14 years, including two separate stints in Denver. But the journeyman lifestyle suits him. He has moved around his entire life. He grew up following his mother around the world. Pamela McGee is one of the great women’s basketball players of her era. A dominant defender and rebounder who often took a backseat to college teammates Cynthia Cooper and Cheryl Miller, McGee was known, more than anything, as a winner. Two Michigan state titles in high school, two NCAA titles at USC, and an Olympic gold medal in 1984. When the WNBA held its inaugural draft in 1997, McGee went second. She was 34 years old.

Up until that point, elite American women’s basketball players had no real options to play professionally at home, so after finishing college, they either went into another field or went abroad. When JaVale was born in 1988, Pamela was already four years into a globe-spanning pro career. “I took this 9-month-old baby overseas,” she says, “and I just said, ‘We’re gonna figure this out.’” His earliest memories on the basketball court were in Brazil, where he tagged along to practices and games, getting up shots when the court was free. “I lived in all these foreign countries,” he says, “but I was so young that I didn’t even really understand what a foreign country was. I was just like, ‘Well, I’m here. I guess this is where we live now.’”

He was tall and athletic from early childhood, but he barely thought about his future, rarely about college and never the NBA. In high school, Pamela laid out a plan for his development that included a transfer from his school in Michigan to a small rural Christian school as a junior so he could get more playing time, then a transfer to a school in Chicago as a senior so he could toughen up. McGee simply did as she directed him, never questioning her expertise. “She has the accolades and everything,” he says, “so who am I not to listen to her?”

His mother rarely thought about an NBA future for her son, as well, until one day, in 2003. Pamela, then an assistant coach with the WNBA’s Detroit Shock, remembers standing next to then-Pistons guard Chucky Atkins on the floor at the Palace of Auburn Hills, where the Pistons had invited a prospect to a private workout before the draft: Darko Milicic. “I’m watching him, and I turn to Chucky and say, ‘This is the no. 2 pick?’ And he says, ‘Yep.’ And I stood there, and I said to myself, ‘Wow. Maybe my son really does have a shot.’”

McGee went to college at Nevada, where he remained incredibly raw. But, he says, “I had the tangibles.” He was a legit 7-footer with a 7-foot-6 wingspan and a 31 ½-inch vertical leap, hands so massive they seemed to engulf the ball. “You knew,” says then-Nevada coach Mark Fox, “whenever he had the chance to mature physically, he had this length and balance and grace as an athlete, and these hands that very few players have.” After his sophomore year, McGee declared for the 2008 draft and was chosen 18th by one of the most dysfunctional franchises in recent history: the late-aughts Washington Wizards.

Life in Washington?

“Rocky,” McGee says.

The Wizards averaged 23 wins over McGee’s first three seasons. Pamela says she told her son, “I’ve played on championship teams. This is not it.” She remembers him saying, “This is the NBA! They know what they’re doing.”

They did not, in fact, know what they were doing. The Wizards ran through three head coaches in McGee’s first three years. He started to feel lost, unsure of his role: “You’re not a lottery pick, where they’re forcing you to grow up, saying, ‘You’re gonna play 30 minutes in this game, and you’re gonna figure this shit out.’ And you’re not a second-rounder, where you’re not playing at all. You’re in the middle ground where it’s like, ‘I’m playing, but I really have no idea if I’m playing the right way.’”

The most famous moment of dysfunction came in McGee’s second season, when teammates Gilbert Arenas and Javaris Crittenton pulled guns on each other after practice. The story has been told many times by many players, but McGee gave his version last year on Shannon Sharpe’s podcast, Club Shay Shay. McGee, Crittenton, Arenas, and former teammate Earl Boykins were playing the card game booray on a flight. They were gambling on the game, and McGee owed Boykins some money. He had a wad of cash in his hand, but said he would pay on the next flight, as he said was the typical practice.

“And Javaris chimes in,” McGee said on Sharpe’s podcast, “saying, ‘You can’t have that money in your hand and not pay him.’” Arenas then interjected, McGee remembered, saying to Crittenton, “Why are you worried about their business? That’s got nothing to do with y’all.”

McGee continued: “So they go at it, words exchanged.” Afterward, McGee thought the conflict had ended. Everyone left the plane, went their separate ways, until the next time they showed up at the facility. Arenas had brought four guns, and told Crittenton, “Pick one.” Crittenton responded by pulling out his own gun, already loaded, and aiming it at Arenas.

Both players pleaded guilty to charges stemming from the incident and were suspended for the rest of the season by the NBA. In 2015, Crittenton pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter after killing a 22-year-old woman named Julian Jones in Atlanta and was sentenced to 23 years in prison.

While the Wizards devolved into a dysfunction, McGee showed off his talent while still, more often than he’d like, making plenty of on-court mistakes. He missed some dunks, got called for some clear goaltends, blew some defensive assignments. All of it began to fuel the perception that McGee was, as he puts it, “a dumbass.” This is the one perception that seems most upsetting to people I talked to. “If you have one conversation with him, you know he’s extremely intelligent,” says Fox. “That was obvious in every interaction and every academic report.” As a player, though, Fox says, “He was very green.”

All athletes make mistakes. But with McGee, there was something about the way those mistakes looked. “Even for an NBA player, his body movement is so different from what we’re used to seeing,” says Iguodala, a former teammate. McGee is listed at 7 feet but somehow looks taller. Iguodala calls him “a legit 7-2.” Bodies that big rarely try to move the way McGee moves. “So when things out of whack happen,” says Iguodala, “it looks extraordinarily awkward. He can do 20 things right and three things wrong, but to the rest of us, those three things really stand out.”

Off the court, McGee was, well, a goofball, the rare athlete to inspire BuzzFeed listicles such as, “21 Reasons You Should Be Following the NBA’s Weirdest Player on Twitter.” On YouTube, he created an alter ego named “Pierre,” and posted, among other things, his worst pickup lines. (“Is that your breath? It smells like angel doo-doo.”) He and teammate Nick Young filmed themselves trying the “cinnamon challenge.” He once tweeted about buying a pet platypus, then scolded journalists for writing about the fact that he bought a pet platypus. (He did not. It was a test. The media failed.)

In games and practices, he says he wasn’t assertive enough in seeking out guidance from the teammates and coaches who could help him get better. The constant coaching turnover kept him from getting the nurturing needed for a player with his raw skill set. “You need to work harder,” he remembers coaches saying. “How do I work harder? Give me some examples. What am I supposed to do?”

After the Arenas-Crittenton incident, the Wizards gathered in a pregame huddle and Arenas pretended to shoot his teammates with his fingers, and McGee and several others fell to the floor laughing, as if they’d been shot. For that, they were each fined $10,000. After that, McGee says, “There was this dark cloud over that team. The perception was that every guy on the team was an asshole.”

Not long after this, Shaqtin’ a Fool started. Immediately, McGee was its biggest star. At the end of the 2011-12 season, Shaq declared McGee the segment’s season MVP, unveiling a countdown of his five lowest moments. Here was McGee spiking a ball into the stands on an obvious goaltend, followed by McGee dribbling out of bounds. Here he was missing a dunk and getting blindsided by a screen. Then, finally, here was McGee missing a shot and sprinting back on defense, unaware his team had gotten an offensive rebound, running as fast as he could while the other nine players wondered where the hell he was going.

Shaq narrated. Charles and Kenny laughed along. Ernie let voters know where they could vote for McGee’s worst play of the season. Tune back in on Thursday. They would reveal the results then.

In 2012-13, McGee was named Shaqtin’ a Fool’s MVP for a second year in a row. (At this point, there had been only two seasons of the segment, so he was, by any definition, its GOAT.) When McGee was interviewed by the NBA on TNT crew one night, he said, “I don’t watch Shaqtin’ a coon.”

The crew laughed it off, and then Johnson referred to O’Neal as McGee’s “biggest fan.”

“I don’t know,” McGee said to Johnson. “He’s more like a bully.”

“OK, let’s watch the game on TNT ... what are they talking about? Kobe had a great game, LeBron had a great game, JaVale’s a dumbass, Kevin Garnett had a great game, OK cool, that’s normal.”

McGee tried to shrug the segments off at first, until he realized how they were impacting his perception across the league. “This is going on TNT every time LeBron plays, every time Kevin Garnett plays, when Kobe’s in the conference finals. It’s like, ‘Here we go, Shaqtin’ a Fool.’ This is going into millions of people’s heads.” He starts waving his hands, goes into a mock-serious tone. “Hey! This guy’s dumb! This guy’s dumb! Let’s make a whole segment about it! He’s an idiot, look! Hahahaha!”

He shakes his head, then holds up an invisible remote control, taking on the voice of a fan. “OK, let’s watch the game on TNT, let’s see here, what are they talking about? Kobe had a great game, LeBron had a great game, JaVale’s a dumbass, Kevin Garnett had a great game, OK cool, that’s normal, that’s cool. Now I’ve watched my NBA for the week and I know what’s going on.”

And so, to many, that’s who McGee was. A dumbass. “It’s coming from one of the greatest centers ever,” he says. “People are gonna believe what he says, no matter what it is.” I ask McGee about the idea that criticism, and even mockery, comes with the territory of being famous, that the right to fail in private is given up by anyone who does public work.

“At first I thought the same thing,” he says. “‘This comes with the territory.’ But eventually, it gets to a point where I’m like, ‘No. This does not come with the territory.’” He pauses for a second, thinking of an example. “If Stephen A. Smith goes on TV and says, ‘You suck. Your team paid $100 million, and you’re not putting up 20 and 10 like you’re supposed to.’ That comes with the territory. As a player you have to take that. That’s his job. But if you’re on TNT every night being made fun of? Even when your team isn’t playing? They’re just showing bad highlights of you to laugh? I’m sorry. That doesn’t come with the territory.”

Iguodala is one of the league’s most respected players. When he played in Denver, in 2012-13, he quickly became one of McGee’s biggest supporters in the league. “I realized his brain actually worked,” says Iguodala. “And I don’t even just mean from a basketball standpoint. He was one of the more high-IQ individuals I had ever been around.” Iguodala saw McGee tinkering with a drone, taking it apart and putting it back together, and he talked with him about business and politics and history. But he also noticed the way McGee practiced. “We had good bigs on that team,” Iguodala says. No stars, but several guys who played critical roles. Kosta Koufos, Timofey Mozgov, Kenneth Faried. “And he was killing those guys every day in practice.”

But McGee was never a starter in Denver. According to Iguodala, head coach George Karl wasn’t McGee’s biggest fan. “The way George handled it,” says Iguodala, “it was more personal than having to do with his talent. JaVale had gotten paid, and George might not have respected the process of him getting paid, but the performance was there.”

Karl was fired after the season, but McGee suffered a stress fracture in his shin and struggled to stay on the floor. In 2015, Denver traded McGee to Philadelphia, who immediately released him, eating his $12 million salary for the following season. Iguodala, now playing for Golden State, remembers suggesting to the front office that they add McGee. “They thought I was joking,” Iguodala says. “That was sad for me. This guy puts in the work, and he has all the talent and all the intelligence, but it just feels like he’s had to prove himself over and over and over again.”

McGee signed with Dallas instead, but in the 2016 offseason, Iguodala tried again. “I knew him and Steve Kerr would get along,” Iguodala says, “because Steve respects smart individuals. And I knew the shot-blocking, the lobs, the jokes in the locker room, all of it would help us.” Iguodala says he takes pride in his track record on player recommendations, and after helping the team to two consecutive Finals appearances, he hoped he’d built up enough good will with Warriors brass for them to hear him out. “I said, ‘Steve, you’ll really like this guy. [General manager] Bob Myers, trust my word. If it wasn’t real, I would never bring this to your attention.’”

I had a preconceived notion about JaVale before he got here that turned out to be completely false.Steve Kerr

So McGee went to training camp with the Warriors on a non-guaranteed deal. “He was nervous about that part,” says Iguodala. “Because players in this league always say to each other, ‘Once you’re on a minimum, that’s where you stay.’ You get stuck.” McGee, though, wanted to show that he could play winning basketball, that he knew how to find and fill a role. He’d been on playoff teams in Denver and Dallas, but nothing like this. The Warriors had just won 73 games a year earlier and then added Kevin Durant.

While talking with McGee, I find myself wondering what it was like, as someone known for his raw gifts and his televised lowlights, to find his place on a team engineered to be one of the best in NBA history.

“It was easy breezy, to tell you the truth,” he says. Just like the culture in Washington made it tougher for a raw young player to grow into his talent, the culture in Golden State made everything click into place. “The message was simple,” he says. “JaVale, you are going to dunk every fucking basketball. You’re going to block shots. You’re going to be a monster on defense.” And now, when describing his early experiences with Golden State, McGee grows animated. “And you’re going to be able to do that because our defensive concepts are amazing. Our team communication is amazing. And everyone else on this team is going to do their job exactly like you’re going to do yours. Because that’s just how it is when you’re on a championship team.”

McGee had trusted his mother’s basketball wisdom when he was in high school; now, he was putting his trust into Kerr and the championship experience of his teammates. He did the role assigned to him. Through his two years in Golden State, he shot 70 percent from the floor in the playoffs and Finals, starting 10 postseason games and winning back-to-back championships. In between, he kept his goofy side alive by filming the “Parking Lot Chronicles” videos in which he joked with teammates and fans after games. He celebrated his first title with a tweet that captured the story of his career more succinctly than this or any article ever could.

“I had a preconceived notion about JaVale before he got here,” Kerr later said, “that turned out to be completely false.” Midway through his first season with Golden State, McGee was playing regularly off the bench, providing important frontline depth to a Warriors team that was tearing through the NBA. He was also, from time to time, making mistakes. Shaq took notice. Five years after McGee was first named Shaqtin’ a Fool MVP, Inside the NBA aired still another segment dedicated to laughing at his blunders. Finally, McGee decided he’d had enough.

He tweeted at Shaq. Shaq tweeted back. You’re welcome to scroll through the full back-and-forth if you’d like, but, in summation, Shaq told McGee that even though he now played for a championship-level team, he would still, now and always, be known for Shaqtin’ a Fool.

The Warriors came to McGee’s defense. Durant called Shaq “childish” and said, “JaVale works extremely hard. He has come in here and done so much for us as a player. He only wants to be respected, just like anybody else.” McGee emphasizes that many casual fans knew him only through the TNT segment, but that if someone cut together the worst plays of any player, even the all-time greats, they could look incompetent, too. Durant seized on this idea, pointing directly at O’Neal. “Shaq was a shitty free throw shooter,” he said. “He missed dunks. He air-balled free throws. He couldn’t shoot outside the paint.”

Iguodala acknowledges the appeal of the Shaqtin’ a Fool segments, but he says the constant ribbing of McGee crossed a line. “It’s funny,” he says, “but most guys are just on there a couple times and they move on. With him it was all the time. And it’s sad because there’s a lot of people that don’t do their homework, and they don’t understand who this guy really is.”

McGee said it was then, after he went after Shaq on Twitter and got the support of his teammates, that he finally felt the perception around his career starting to change. “I said what the fuck I had to say,” McGee remembers. “Enough is enough, bro. I don’t understand. You’re one of the most dominant centers ever. All the fame, all the fortune, everything. What are you getting from this? It just never made sense to me.”

McGee was back with the Nuggets last spring, but his run of championships seemed to be nearing its end. He’d won another title, in 2020, with the Lakers, yet after bouncing to Cleveland and then to Denver, he faced a sweep in the second round at the hands of the Suns. After barely playing in the first three games of the series, McGee played 20 minutes in Game 4. For the Nuggets, it was ugly. The loss seemed assured from the moment they took the floor. Only McGee didn’t play that way. He was flying around both sides of the court, injecting energy into a listless team. The Suns players took notice. “I pay attention to everything,” says Paul. “And one of the things I always notice is, ‘How is a guy playing when it’s a blowout?’ Some guys go through the motions. It’s like they think they’re too good for those minutes. And in that game, nobody would have blamed JaVale if he did that. But he didn’t. And when I see someone who’s doing that, I notice.”

There would be no fourth ring in 2021. McGee sought a gold medal instead. Team USA was going to Tokyo. McGee wanted a spot on that plane. He didn’t fit the profile of the superstars that tend to fill Team USA rosters, but he knew he could fill a role around them, like big man Tyson Chandler did in 2012. Four years before he was born, McGee’s mother had won gold in Los Angeles. He wanted to become the first mother-son duo in the history of the Games to win Olympic gold medals.

He called Sean Ford, the men’s national team director for USA Basketball, weeks before the roster was finalized. “I understand y’all don’t have a center yet,” he told him. “If you’re looking for one, I’m available. I’ll even be an alternate. I’m ready. I’m locked in, in shape, and ready to go.” Ford says he rarely gets calls like that, at least not directly from players. As they continued constructing the roster, he kept it in mind.

Eventually, Kevin Love withdrew days before the team was set to fly to Japan. Scrambling to find a replacement big, Ford thought of McGee. “He was long, he could defend and rebound, he could switch onto smaller players,” says Ford. “All of that could help us.” The next morning, McGee awoke to several missed calls from his agent. Could he be in Vegas by tomorrow?

Said McGee: “I’ll pack my shit up ASAP.”

McGee got only spot minutes in Tokyo, but he averaged 6.3 points and shot 77 percent from the field. And after its early struggles, Team USA avenged a loss to France to win the gold. “I think that gold medal meant even more to me than it did to him,” says Pamela McGee. “For us to be mother and son, both with gold medals? Having your children follow in your footsteps was powerful for me.”

While in Tokyo, McGee also had a few conversations with Suns coach Monty Williams. He remembered his players mentioning how hard McGee played with the series essentially over. The Suns had gone on to reach the Finals, but they’d been undone, in part, because they lacked the bodies to throw at Giannis Antetokounmpo when starting center Deandre Ayton went to the bench.

McGee signed a one-year deal with the Suns, and along with midseason addition Bismack Biyombo, he’s provided the frontcourt depth the Suns once lacked. Well into his 30s, with most of his 2008 draft classmates long out of the league, McGee keeps getting rotation minutes for title contenders, even as the center position wanes in importance around the league. “We would not be in the position we’re in without him,” Williams says. “We would not have the defense we have without him at the rim, doing what he does. He’s been huge for us.”

McGee looked at Phoenix’s blend of youth and experience and thought he saw a chance to be a part of something he missed out on as a young player but had come to relish later in his career. “They drafted most of their stars,” he says of the Suns. “So all these guys got to grow together. They know each other’s temperaments. They know he likes being talked to like this, and he doesn’t like being talked to like that. And then you take that mix, and they added a mega mind in Chris Paul, and it just makes everything fit together.”

There are still those moments when something goes awry, the moments when you can imagine Shaq sharpening his knives. In Game 2 against Dallas, McGee flew out to close out on Maxi Kleber, and he jumped, out of control, and landed on top of him, sending them both to the ground and Kleber to the line for a four-point play.

But then there are moments when that athleticism and grace are paired with the instincts and effort, when he does something that few humans his size could ever do. Like in Game 1, when he switched onto the Mavs’ Luka Doncic, a nightmare assignment for any big man in the league. But he stayed in front of Doncic, patient and well-positioned, until Doncic tried to cross him up and McGee reached low, poking the ball away.

McGee then scooped up the ball and began loping his way down the court, using only three dribbles to get from one 3-point line to the other, until he rose, just inside the free throw line, headed toward the rim. McGee charted a similar path to the basket years ago, when he was still with the Wizards. But when he went up for the dunk, the ball slipped out of his hand. On TNT that week, they laughed and howled, because here was JaVale again, unable to get out of his own way.

But now he rose with confidence and power, head at the rim and elbow well above it, and he dunked the ball and gave no reaction, just sprinted back to the other end. The arena swelled to the point of bursting. On the bench, his Suns teammates looked giddy, and I thought back to a moment in our interview, when McGee leaned back on his couch, took a sip of his Sprite, and theorized why so many of the league’s great teams of the last half-decade have found a place for him on their squad.

“My energy,” he said. “It’s fucking infectious.”