Every Pixar Movie, Ranked

Ahead of the release of ‘Lightyear,’ the Ringer staff ranks all 25 of the studio’s animated filmsAhead of the release of Lightyear, The Ringer is hosting Pixar Week—a celebration of the toys, rats, clown fish, and more that helped define one of the greatest studios of the 21st century. At the heart of the occasion is the Best Pixar Character Bracket, a cutthroat tournament to determine the most iconic figure of them all. Check back throughout the week to vote for your favorite characters and read a selection of stories that spotlight some of Pixar’s finest moments. To infinity … and beyond!

On Friday, Pixar will release its 26th movie, Lightyear. The studio has spent the past 27 years elevating the animated film genre with stories that appeal to both children and adults. Its movies are visually engaging tales full of whimsy and humor that also examine hard truths and complex emotions. Pixar’s been making us laugh and cry in equal amounts for two decades, is what I’m trying to say.

With the release of Lightyear approaching—and with The Ringer’s Best Pixar Character Bracket in full swing—it felt like as good a time as any to update our ranking of Pixar’s catalog. The ranking was determined by a purely democratic process in which members of the Ringer staff were asked to rank their top 15 Pixar films. The movies were then awarded points based on where they landed, with a first-place vote equaling 15 points, a second-place vote equaling 14, and on and on. Since this ranking was originally published in 2018 and then updated in 2021, it has been updated to include two subsequent releases: Luca and Turning Red. It has also been updated to account for more amorphous developments like shifting opinions, earned wisdom, and big life experiences that might have an effect on how one perceives a film. The beauty of a Pixar movie is how one’s relationship to it can evolve over time. So without further ado, here is The Ringer’s official ranking of every Pixar movie. —Andrew Gruttadaro

25. Cars 3

24. Cars 2

(Cars 3 and Cars 2 received zero total votes in the deliberation process, and will continue to be known as “the Pixar movies everyone pretends aren’t actually Pixar movies.”)

23. The Good Dinosaur

When we did this ranking in 2018, The Good Dinosaur was part of the ignominious group of Pixar movies that didn’t receive a single vote. Four years later, it’s still ranked extremely low—but at least this time someone actually voted for it.

22. Monsters University

Megan Schuster: Like so many of the glorious Pixar movies that came before it, Monsters University hit my life at the perfect time. The film, released in 2013, dropped the summer between my sophomore and junior years of college, in that uncertain time when you have to start recognizing graduation and the World Beyond School as no longer distant entities, but fast-approaching realities. Monsters University, a prequel to the Pixar hit Monsters, Inc., focuses on the lives of Mike and Sully before they hit the professional scare floor, showing their trials and tribulations in college and how their unlikely bond was formed.

Watching the movie back now, three years removed from my own graduation, it makes me nostalgic for all the dumb parts of college—the bunk beds; the frat parties with the sticky floors; the 101 courses you couldn’t get out of no matter how much you begged the registrar; the roommates who drove you crazy but, weirdly, when you look back on it, also turned out to be your best friends. Monsters U may not be the best Pixar film (OK, it’s most certainly not even close), but it demonstrated that life’s major themes, those universal through lines that the studio is so adept at portraying—the desire to fit in, the challenge of doing the right thing, the fear of chasing your dreams—don’t disappear when we grow up. They just age with us.

21. Finding Dory

Ben Lindbergh: Thirteen years elapsed between the releases of Finding Nemo in 2003 and Finding Dory in 2016, which seems like a dangerous span of time between an animated movie and its sequel/spinoff: long enough that the kids who watched the former have aged out of the audience, but not long enough that they’ve created tiny Pixar consumers of their own. Yet Dory, which reunited Nemo director Andrew Stanton and stars Ellen DeGeneres (Dory) and Albert Brooks (Marlin), did billion-dollar business, becoming the highest-grossing animated movie ever in the domestic market and ranking second behind Nemo in inflation-adjusted dollars on the all-time Pixar earnings leaderboard.

All those years later, it wasn’t imperative that Pixar expand the Nemoverse, but unlike a few other Pixar prequels and sequels, Dory didn’t feel like an extraneous cash-in. Set one year after Nemo, it mined the same strain of subsurface separation anxiety that drove its predecessor, sending Dory, Marlin, and Nemo—played by Hayden Rolence instead of original actor Alexander Gould, whose voice had changed in the interim—in search of Dory’s parents, self-sufficiency, and self-esteem. The cast was stacked (Ed O’Neill’s octopus deserves his own spinoff), the visuals were revamped, and the balance between laughter and tears was still sublime. The only notable knock on Dory is that it’s not Nemo: The first film’s setting and story structure were worth revisiting, but they weren’t as striking the second time around.

20. Onward

Rob Harvilla: Onward hit movie theaters in March 2020, just weeks before COVID-19 brought America to a standstill, which only adds to the bittersweetness of this odd, low-key, and endearingly personal ode to two lovable teenage elves who try to resurrect their dead father but only manage to resurrect half of him—the bottom half. Pixar vet Dan Scanlon, in his second director gig after 2013’s workmanlike Monsters University, brings a winsome mixture of whimsy (the walking pants) and melancholy (the walking pants convey a profound sadness somehow) to this shaggy tale of latent magic powers and bitchin’ airbrushed custom vans: It’s a bizarre jumble of wacky fantastical flourishes and big feelings that declares Pixar’s intent to not just crank out Monsters Inc. sequels for the next 20 years. Bonus points if you watched it in a movie theater with two young sons munching popcorn on either side of you.

19. Brave

Michael Baumann: Brave is remembered as a disappointment, and probably correctly so, particularly coming on the heels of Disney’s Wall-E-Up–Toy Story 3 heater. (We do not talk about Cars 2. It is Of The Dark Place.) When the expectation is “this movie must make $700 million and sell a bazillion toys and make every year-end list and leave children clapping with glee and grown-ups sobbing as if chopping onions while thinking of a beloved pet who died” there’s nowhere to go but down. Particularly when Brave was also supposed to feature breathtaking animation and usher in a new era of feminist modernity for Disney princesses. That was an impossible bar to clear.

But you know what? Brave was still pretty good. The animation is great—Merida’s mop of frizzy red hair whipping around against the blue-green backdrop of woods and tartans is the film’s enduring image, though my favorite moment is the slo-mo Robin Hood–style archery contest, when the arrow’s fletching cuts Merida’s cheek as she releases it. Kelly Macdonald’s great, as always, in the lead role, and Merida’s brothers turned bear cubs are in the best tradition of Disney comic relief. Emma Thompson’s wasted in this movie, and it’s kind of haphazardly paced. Also, it’s not Wall-E. But as something to stick your kindergartner in front of for an hour and a half and deliver a few laughs and an uplifting message? It’s just fine.

18. Cars

Shaker Samman: I could tell you about how Cars is a movie about overcoming hubris, and the value of humility and all the other wonderful life lessons peppered in along the way. We could talk about how the preordained future of racing Lightning McQueen (Owen Wilson) is a jerk to the folks he meets in Radiator Springs, and continues to treat them poorly until he wisens up and realizes he can learn something from them. There could be theses written about the love story between Lightning and Sally Carrera (Bonnie Hunt)—how exactly does that um, work?—and someone surely has made a short film about Paul Newman’s performance as the former champion turned wise curmudgeon Doc Hudson. But most Pixar films mirror those high notes. What sets Cars apart is its climax.

After Lightning heeds Doc’s advice on how going the wrong way can actually help him go in the right one, no one stands between him and the Piston Cup he so desperately craves. But when Chick Hicks (Michael Keaton) wrecks the King (Richard Petty), he brakes hard. While Hicks sprints through the finish, Lightning drives back, and pushes the King across the line of his final race. So much of peak television has sought to deal with a simple question: Can a bad person become good? In one simple act, Pixar answered. Ka-Chow.

17. A Bug’s Life

Kate Halliwell: The most difficult obstacle of A Bug’s Life wasn’t the central plot about an ant colony fighting off tyrannical grasshoppers—it was having to follow in the footsteps of Pixar’s first and most beloved film. As the second Pixar movie, A Bug’s Life was a clear attempt to cement the studio’s cred as an animation powerhouse following the success of Toy Story. (Spoiler: It worked.) While some look back at A Bug’s Life as a disappointing follow-up to the greatest Pixar film ever, it stands alone as an entertaining, vibrant take on a classic underdog tale. Flik, an inventive ant outsider, journeys to find a way to protect his colony from its evil oppressors. He mistakes a group of circus performers as mighty heroes, and brings them back Seven Samurai–style to save his people. Including Francis, a tough ladybug voiced by Denis Leary, and Heimlich the caterpillar, an all-time great Pixar character, the ragtag circus bugs are the highlight of the movie. The final act of the film is an inarguable delight, as the team crafts a huge bird sculpture in order to scare away their foes and return peace to the meadow. And don’t forget the faux outtakes, which perhaps hold up better than any other aspect of the film 20 years later.

16. Luca

Miles Surrey: If there’s such a thing as a Pixar house style, then Luca feels like a notable departure for the studio. A heartwarming tale of friendship set in an idyllic seaside town in Italy, Luca follows two sea creatures who turn into humans on land and spend a summer training for a local children’s triathlon so they can win enough money to buy a Vespa. (As if the movie couldn’t get any more Italian, the triathlon involves biking, swimming, and pasta-eating.) But while Luca does have an important message for kids about accepting people (or sea creatures) who happen to be different, the film coasts on the kind of playful, carefree spirit more commonly associated with Studio Ghibli. It might not rank among Pixar’s finest movies, but Luca is still a crowd-pleaser that shows the studio can expand its boundaries without sacrificing quality.

15. Incredibles 2

Dan Devine: This is the B story of a soaring drama with a $200 million budget that grossed $1.2 billion worldwide—a sweeping story about the nature of heroism and how we relate to reality in an ever-accelerating, media-saturated environment:

A father better equipped to break things than fix them has to accept that a life of punching the bad guys (Pow! Pow! Pow!) won’t help him address the complex emotional and developmental issues that a parent faces. He struggles with a bruised ego; with the jarring shift from putting work first to becoming a primary caregiver; with learning how to help his daughter process heartbreak (that’s partially his fault) and his son learn math (that he himself finds confusing and frustrating); with figuring out how to take care of a baby whose needs he doesn’t really understand (and who sometimes becomes a flaming extra-dimensional monster); and with doing it all on zero sleep.

He can’t admit he needs help—that he’s not strong, smart, or capable enough to do it all on his own, because that sort of hyper-competence and invulnerability is central to how he sees himself. Because without it ... shit, man. Who even is he?

I’m not projecting. You’re projecting.

(For the record: My 6-year-old loves the colorful and stylish action, my 3-year-old thinks Jack-Jack exploding is very silly, and my wife appreciates Elastigirl being a total badass professional all on her own. So maybe we’re all projecting.)

14. Soul

Katie Baker: Soul is a movie that spoke directly to me, in ways that were so specific that they almost made me suspicious. A dread pirate sailing across existentia, wearing tie-dye, and blasting the Dead? Hey now! One hundred and seven minutes worth of focus on mortality and purpose and legacy, peppered with jokes about the Knicks, therapy cats, and Wall Street bros and soundtracked by Atticus Ross and Trent Reznor? OK, so basically my Twitter timeline. A floating consortium of preternaturally serene Gaia types overseeing a chaotic, liminal realm? Sounds like the parents’ meetings at my sons’ preschool.

Said sons, on the other hand, came away from the movie laughing about pizza, poop, and butts, and incorrectly believing the main character is named “Soul.” Of a piece with other Pete Docter–led Pixar productions such as Up and Inside Out that aren’t afraid to wade deep into the emotional and metaphysical muck, Soul is a feat of world-building, whether that world is “the jazz circuit” or “humanity’s corporeal existence”—all while throwing in enough sight gags to satisfy its supposed target audience. It made me cry; it made my kids chuckle at a talking cat. All in all, a successful Pixar film.

13. Monsters, Inc.

Alison Herman: If your favorite SNL cast is inevitably the one that was on the air while you were in high school, your favorite Pixar movie is undoubtedly one released when you were between the ages of 8 and 12. You’re young enough to have the intensity of feeling that can imprint a movie in your brain for decades to come, but just old enough to understand the emotional sophistication that comes with all the best Pixar projects. After all, this is the company’s specialty: combining the sweetness and imagination of childhood with the skill and intelligence of maturity. It’s kid-like without being condescending.

To my mind, Monsters, Inc. is the movie that best exemplifies that Pixar blend, even if you remove the nostalgia factor. (I had just turned 8 when it was released.) The very real terror of staring into the dark without one’s nightlight is taken completely seriously, then assuaged with the ingenuity of a whole monster economy in which children’s screams literally keep the lights on. With all due respect to Billy Crystal, John Goodman’s vocal performance ties the whole thing together: He’s got a menacing growl that transforms into a nurturing purr as he goes from Boo’s tormentor to her caregiver. He sounds like a hug.

As a kid, the Office Space–like drudgery of the scream factory flies right over your head, though I do recall my dad being especially entertained by Roz. As a grown-up, though, there’s an additional layer to Monsters: the contrast between the wide-eyed creativity of its world-building and the stultifying corporate culture that comes with any job, even one in a parallel dimension. Pixar knows how to cater to every audience, from kids to the parents they’ve dragged with them to the theater. Monsters, Inc. sticks with us as we age from one into the other.

12. Toy Story 4

Lindbergh: There didn’t have to be a sequel to Toy Story 3, which wrapped up the bittersweet story of Woody and Andy in satisfying fashion. But between Pixar’s desire to spend more time with its most iconic characters and the prospect of banking a billion dollars at the box office, the will was there to make a fourth film, which arrived in 2019 after another long layoff. Despite its protracted gestation and the turmoil and turnover in its creative team, Toy Story 4 mostly measured up to its beloved predecessors, garnering the usual “universal acclaim” from critics and “A” from audiences polled by CinemaScore. The movie grossed slightly more than Toy Story 3 (both domestically and globally) and took home another Academy Award, making Toy Story the first franchise to win the Oscar for Best Animated Feature twice. The movie marked the end of an era in more than one way: After Toy Story 4, Pixar forswore sequels and devoted itself to starting anew.

In addition to doing justice to the series’ familiar faces and voices, Toy Story 4 found room for memorable newcomers Forky, Gabby Gabby, and Duke Caboom, and it provided a fitting final film credit for Carl Reiner. (Sorry, Carl Reineroceros.) A toy’s lot in life is to lose the love of its owner, but Toy Story 4 presented a radical reimagining of the life cycle we saw in the earlier films. This time, Woody chooses to pursue a lasting love with Bo Peep, and the fate that he’d feared—becoming a “Lost Toy”—turns out to be a happy ending. It’s also an emotional one, which made audiences as weepy as Tom Hanks was when he recorded his final line. Animated characters may be immortal, but movie creators, composers, and cast members aren’t, and in 2019, Hanks pronounced Toy Story 4 “the end of the series.” But after capturing the hearts of three cohorts of kids over the years, Toy Story will likely live on in other forms, extending its travels to spinoffs and beyond.

11. Turning Red

Khal Davenport: Domee Shi’s follow-up to her critically-acclaimed (and Academy Award-winning) short, 2018’s Bao, is an important one. Turning Red, which tells the story of a 13-year-old Chinese Canadian teenage girl who one day discovers that she’s inherited her family’s ability to turn into a red panda when she gets excited, is the first Pixar film to be solely directed by a woman. It’s also one of Pixar’s best films in years. Shi clearly understands both the teenage Mei and her mother, Ming, and their relationship—a tug of war between hiding what’s inside and letting your freak flag fly—is the heart of this film. Extra kudos to Pixar for giving Shi a platform to tell such a specific tale, one that can be felt by Torontonians and those of us who can’t turn into giant red pandas when they get hype alike.

10. Toy Story 2

Miles Surrey: Pixar didn’t think much of Toy Story 2 when it was first conceived—it was originally pegged as an hourlong, straight-to-video feature. That a sequel to a commercially viable, critically acclaimed children’s movie was even considered on these terms is an impressive window into how moviemaking has evolved in a short period of time. Toy Story 2 deserved a larger platform, building on Woody and Buzz Lightyear’s existential ruminations on childhood and growing up with a surprisingly unrestrained pathos (and with a cowgirl named Jessie, played by Joan Cusack). Seriously, rewatch that musical montage of Jessie slowly being forgotten by her owner Emily as she grew up and tell me you’re not bawling your eyes out.

Toy Story 2 was a rare delight even by Pixar’s lofty standards, a sequel that lived up to the original without being a rehash of old ideas or a cynical cash grab.

9. The Incredibles

Chris Almeida: In 2004, I was an 11-year-old living in a pre-MCU world. Sam Raimi’s first two Spider-Man films were fresh in my brain, and I wanted more. There was a year in between the death of Doctor Octopus and Batman Begins, so my post–blockbuster season snack was The Incredibles. At the time, I enjoyed the things that kids enjoyed: the “Where is my super suit,” Syndrome’s faux-philosophical rants, the slapstick gags, the brassy, cocksure soundtrack. Now, I enjoy the resultant memes, the slicker, dirtier jokes, the design of Edna’s mansion, and, still, the soundtrack. The Incredibles was a movie ahead of its time; it poked fun at the superhero factory before anybody knew about Marvel Phase Three. It had jokes built for forums that didn’t yet exist. And it was good enough that after leaving us all hanging for 14 years, everybody still wanted to pull themselves back onto the cliff for a sequel.

8. Finding Nemo

Andrew Gruttadaro: Yo Up, I’ma let you finish, but Finding Nemo had the saddest opening scene of all time!

The clownfish massacre that kicks off Nemo sets the bar for the emotional gantlet that is the rest of the movie, as a father named Marlin (Albert Brooks) goes on a quest to retrieve his only surviving son after he’s scooped out of the sea by a dentist. It is a movie about the tension a parent grapples with between protecting one’s child and letting him or her experience the world. It is a movie about love, and how so often we can’t understand the way one’s love for us manifests itself. It is pointed and beautiful and immensely rewarding.

But Nemo is one of the greatest Pixar movies ever because of the way it so carefully and meticulously renders marine aquatic life. The jokes are so specific—from Ellen DeGeneres’s forgetful blue tang Dory to “Mine!” to the shark therapy group to “You guys made me ink”—and so tethered to reality, the settings so fully realized. Finding Nemo is like watching an episode of Blue Planet II, with emotional stakes and comedic relief added in. It is my happy place.

7. Inside Out

Lindsay Zoladz: Whenever I need to clean out my tear ducts, I think of Bing Bong. Specifically the cotton-candy-scented imaginary friend’s final scene in Pixar’s 2015 adult therapy session disguised as a children’s movie, Inside Out, when Joy must leave him in the forgotten trash heap of Riley’s subconscious in order to move on and grow up. “Take her to the moon for me, OK?” Bing Bong mutters into the void. The void, naturally, does not answer. Please excuse me while I go rip up several boxes of Kleenex and howl at the moon.

Inside Out is probably Pixar’s highest-concept gambit: Its main characters are abstract emotions, like Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear, and Disgust. (TAG YOURSELF.) It’s a sophisticated dual narrative, simultaneously weaving together the external narrative (as our perilously prepubescent hero Riley moves to a new school) and the internal tumult this is causing among her motley crew of emotions. Because of all the plot mechanics, it’s probably best appreciated by slightly older children—but let’s be real, its lessons of maturity, growth, and acceptance of negative feelings are the sort of gospel that plenty of adults need to hear, too. Pixar’s good like that. In a profile of Inside Out director Pete Docter around the time of its release, the writer Lisa Miller noted that, “In my house, the movie has given us a new way to talk about how we feel.” While riding bikes, she asks her young daughter, “Who’s driving now?” Her answer is inspired by the movie: “Joy, and a little bit of Fear.” Talk about a mind-altering children’s movie.

6. Up

Kate Knibbs: I like grand tragedies, and what’s a more elaborate catastrophe than the inevitability of death, coming for us all, even sweet little old ladies who just want to see a damn waterfall? Up fucked me up the first time I saw it, and has fucked me up every time since. I judge a Pixar movie by its ability to destroy me emotionally, and thus Up is, by my estimation, the best Pixar movie ever, a tale of sad widower Carl (Ed Asner) learning to live after losing his love, with the help of a child and a flying house. Michael Giacchino’s music snagged Pixar its first Oscar for score, deservedly so, and the animated humans are adorable, not creepy like the people in the Toy Story films. But even if the animation and music had been garbage, I’d still love Up, which is weird and funny and possibly the most psychologically honest children’s movie I’ve ever seen, one that is frank about death and aging but insistent that adventures and relationships are still worth it.

5. Toy Story 3

Harvilla: So this is the one where all of young Andy’s beloved toys almost die. Specifically, they almost burn up in a giant incinerator after the usual series of whimsical misadventures that abruptly ceases to feel whimsical in the slightest. “What do we do?” Jessie the plucky cowgirl yelps in panic as the gang is pushed inexorably toward a billowing flame, the colors a nightmarish riot of oranges and reds, the soundtrack clanging and Wagnerian. Buzz Lightyear just sadly takes her hand. And then, for a solid 60 seconds, you watch adorable animated toys resign themselves to death, joining hands and leaning into each other and wincing. When they are rescued by the adorable Claw Alien Guys, you are both relieved and suddenly aware of the fact you are crying.

Toy Story 3 has more conventional delights: Sad Accordion Clown is my favorite character, and his quietly hilarious accordion-backed monologue doubles as the backstory for one of Pixar’s more believable and sympathetic (and unredeemed) villains. But the mournful grace of the incinerator scene is what sticks with you: It is “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” taken to its logical, awful, unsettlingly beautiful conclusion.

Also, there is a Totoro cameo.

4. Coco

Alyssa Bereznak: In the year or so since its release, Coco has earned a reputation as an automatic tear-jerker, one of those movies that fills you with so much sadness and warmth and love that the mere pluck of a guitar string can turn you into a dough ball of feelings. It’s easy to see why. Beyond taking us on a twinkling tour of the Dia de los Muertos–inspired “Land of the Dead,” treating us to some skeletal slap-dash humor, and conjuring a handful of alebrijes straight out of an acid trip, the film confronts some heavy stuff. On a journey filled with heart-wrenching musical tributes and magical marigold bridges to the afterlife, Coco’s guitar-toting protagonist, Miguel, reminds us that we should all do more to honor the memories of our family members—even the ones who made our lives incredibly difficult. And all the while there is the low hum of a humbling universal human truth: that without that remembrance, anyone can be forgotten overnight.

3. Ratatouille

Ben Glicksman: There’s a scene a little more than halfway through Ratatouille when Remy, the lead character and a wide-eyed rat with dreams of becoming a Parisian chef, has an argument with his father, Django, from whom he was separated during the movie’s opening sequence. Remy tells his dad that rather than stay with his family, he plans to live among the humans. In turn, Django takes Remy to a storefront window that displays the bodies of dead rats.

That inspires the following back-and-forth, which encapsulates Remy’s worldview and speaks to the forces that systematically oppose those who aim to transcend their plight in life.

Remy: No. Dad, I don’t believe it. You’re telling me that the future is—can only be—more of this?

Django: This is the way things are. You can’t change nature.

Remy: Change is nature, Dad. The part that we can influence. And it starts when we decide.

Ratatouille explores the push-pull of family versus career, the isolation that accompanies artistry and ambition, and the conflict that comes from questioning one’s identity more honestly than any other entry in Pixar’s catalog. It’s also warm, funny, and transporting in all the ways Pixar is at its best. Just take the movie’s climax, when feared restaurant critic Anton Ego—a character nicknamed “The Grim Eater” who works in a room shaped like a coffin—samples one bite of Remy’s dish and is instantly taken to his childhood, a nod to the nostalgia only the best food and film can evoke.

Ratatouille isn’t Pixar’s most celebrated creation, but it’s a masterpiece nonetheless. It’s a love letter to food, to friendship, to art, and to dreamers. Anyone can cook.

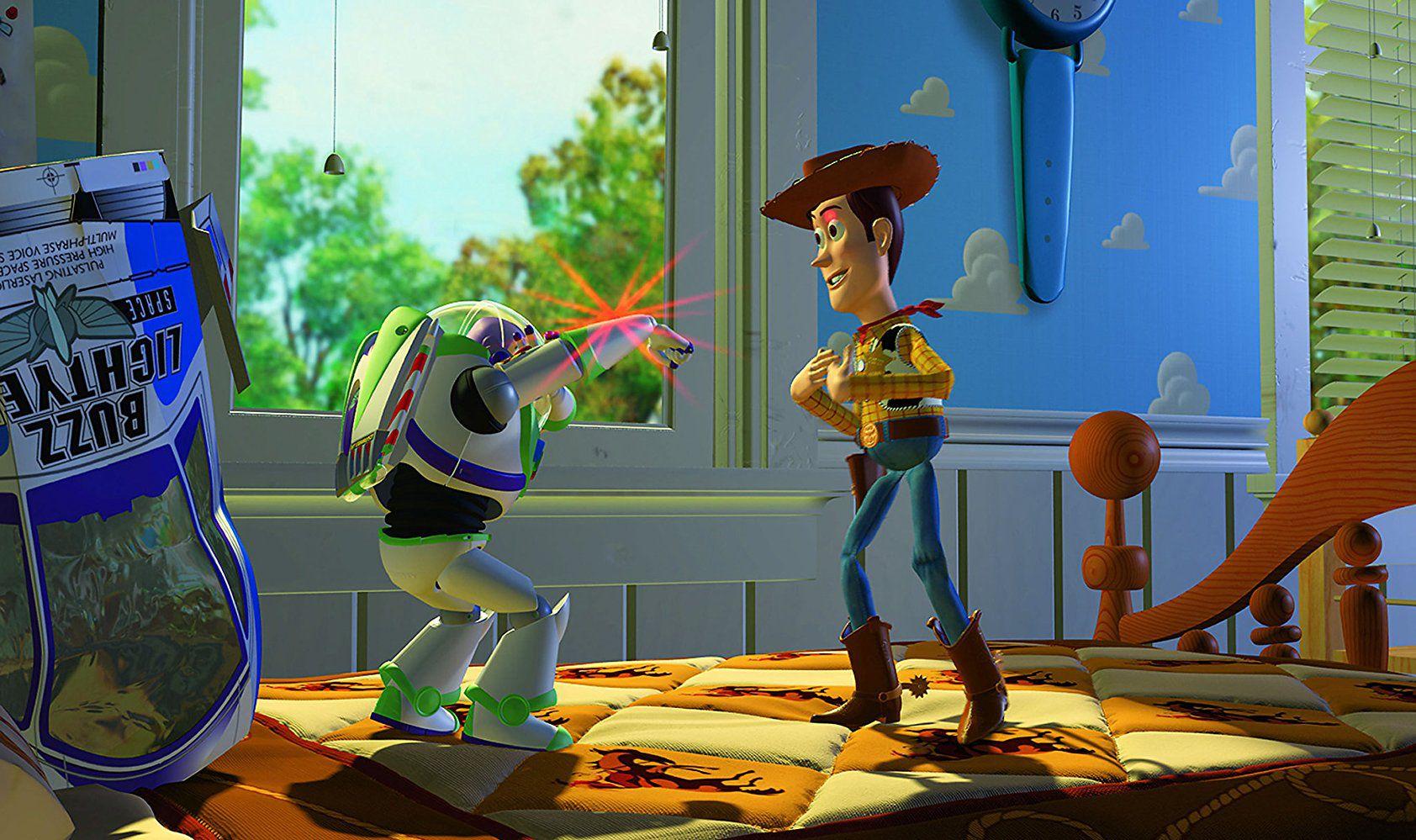

2. Toy Story

Sean Fennessey: It’s hard to overstate what a profound shift Toy Story represented, what a genuinely breathtaking leap it really was. It wasn’t just the first computer-animated feature film ever made, or the first Pixar movie—it also marked a kind of world-building we’d never seen before in a kids’ movie. Maybe that’s because Toy Story isn’t so much a kids’ movie as the embodiment of a group of adults reflecting on what kids’ movies ought to be, what they wish they could be: detailed, unbound, empathic, aspirational, three-dimensional, kindhearted, risky, and above all, sophisticated. While Woody the Cowboy and Buzz Lightyear were pure Pixar inventions—specifically born of a quartet of screenwriters that included Joss Whedon and Finding Nemo’s Andrew Stanton—much of the figures involved were toys of childhoods past: Mr. Potato Head, a Slinky dog, Little Tikes, Army Men, an Etch-A-Sketch, a piggy bank. Canonical toys, the kind that never expire.

Toy Story never expires either. It is one of the most indefatigable franchises created in the past half-century, and the original is a perfect and—at 81 minutes—perfectly compact construction. It appeared at a momentous inflection point in animation. In 1995, Disney Animation Studios released Pocahontas, one of the last significant works before a long fallow period, while Universal Pictures shared the little-seen Balto, the final film from Steven Spielberg’s shuttered and mostly forgotten animation division, Amblimation. It was also the year of the anime classic Ghost in the Shell, and that same year Hayao Miyazaki was deep into production on Princess Mononoke, which would mark the global emergence of Studio Ghibli. Animated movies were on a precipice of something exceeding respect—they were about to become the very best films Hollywood had to offer, as deep and meaningful to adults as to children.

Toy Story was recognized as such, nominated for Best Song (my beloved Randy Newman, who lost, of course) and Best Original Screenplay at the Academy Awards. It was also given a Special Achievement Oscar, the last time the Academy gave out an award of that kind to a wide-release movie. But beyond the accolades and the movie’s staggering box office success, Toy Story is ultimately about a boy grappling with how to put away childish things, what those things really mean to him, and what happens on the other side of fun. It was the first of many things, but its legacy is in the infinity it created. And beyond.

1. Wall-E

Mallory Rubin: In many ways, Wall-E defies categorization. It features one of the defining love stories of our time, but it’s not strictly a romance. It asks us to contemplate what consciousness is, but it’s not strictly a sci-fi saga. It includes a star dance so magnificent it felt like 4K before that was a thing, but it’s not strictly a space opera. It showcases high jinks and pursuits, but it’s not strictly a heist movie. It warns against the hazards of consumption and destruction, but it’s not strictly an environmental warning.

Its genre is humanity, its concerns at once as fundamental and all-encompassing as: Why are we here? What is this all about? What does it mean to be a person in the world? And what does that mean if you’re a robot and your world is a trash heap? Wall-E is about the perils of loneliness and loss and the power of determination and hope. It’s a testament to the belief that we can forge our identities as we see fit, and a reminder that being unable to change the past shouldn’t dampen our desire to alter the future. It’s about two robots and a boot, yes, but it’s also a 98-minute visual treatise on the human condition—a reminder that every squeaky exclamation can be a declaration, and that home is where we make it.