Roger Milla, the Indomitable Lion Who Changed World Cup History

The fifth installment in ‘22 Goals’ features the Cameroonian forward whose goal-scoring feats at the 1990 World Cup in Italy changed the perception of African soccerThe Ringer’s 22 Goals: The Story of the World Cup, a podcast by Brian Phillips, tells the story of some of the most iconic goals and players in the history of the men’s FIFA World Cup. Every Wednesday, until the end of Qatar 2022, we’ll publish an adapted version of each 22 Goals episode. Today’s story involves Roger Milla at the 1990 World Cup in Italy.

1. Tree of Unknown Species

About a year ago, my wife and I were on vacation, and we got a message telling us that a giant maple tree had fallen down at our house.

I think it was a maple tree. I’m awful at remembering plant names. I really want to get better at it. I grew up in a small town in a pretty rural part of Oklahoma, but the plant-identifying part of my brain is somehow a lifelong Upper East Sider.

In my heart, I am a loving cultivator of Earth’s marvelous flora. But my brain looks at a plant and goes, “Green. Boring. Let’s hop in a yellow cab and get lunch at Elaine’s.”

Anyway, now Siobhan and I live in the middle of Pennsylvania, and last year we went up to Maine for a few days. Stayed at this totally lovely little place on the water, read some mystery novels. I highly recommend it. Maine: It’s the Way Life Should Be.

And then, at the end of our stay, Siobhan got a text from our dog sitter saying that a giant tree of some indeterminate species, probably maple, but really tall, could be a California redwood, who knows, but anyway some giant tree—I’m paraphrasing, if you couldn’t tell—just toppled over beside our house.

I think at the time we were sitting in a restaurant having cocktails. And our first thought was, Hm, a tree falling down in front of our house. Our house is really far away. That doesn’t sound very real.

And then the dog sitter texted us photos. And it looked like an earthquake had just taken out the Hundred Acre Wood. It’s dark—it’s nighttime—and there’s this huge thunderstorm raging, and then just this massive snapped-off trunk and debris everywhere and this fallen tree completely blocking the street by our house.

Was it a maple? Now I’m second-guessing myself. I feel like it rhymed with maple? I gotta get a plant book. We have these peonies in our backyard—I think they’re peonies? sort of flowery, bushy things—and I never remember exactly what they’re called, and every time I have to say the word I have a two-second panic attack. Like I’m trying to remember the code to stop a nuclear attack. I’m like, “Why yes, those are lovely flowers on the hnnnng oh god don’t screw it up don’t screw it up … California red...bush?”

So I assume this tree was hit by lightning. Not totally clear why it fell over. There was a storm, obviously. Trees are great at one thing—standing up—until they’re not.

I might only think lightning because it’s so on-brand for this series? Everything in this series seems to get hit by lightning. Including many of my metaphors.

Anyway, luckily the maple (???) tree did not smash any cars or crash headlong through our dining-room ceiling. But it’s still a problem when your tree is blocking both lanes of a two-lane road. The cops are gonna be like, “Excuse me, sir, why are you stopping traffic with your tree,” and I’m gonna have to go, “Because I’m too weak to move it, and also, I’m 600 miles away, drinking French 75s at a sustainable seafood restaurant.”

No way am I saying that to a judge. So from this restaurant in Maine, we had to figure out how to rouse some dudes with chainsaws to go out and carve up the tree at, like, 9:30 at night.

It’s the most I’ve ever felt like a 19th-century robber baron. I’m throwing down gin fizzes in literal Maine like AHAHA YES, DISTANT LABORERS! TOIL ON MY BEHALF! TOIL, I SAY!!!

Mildly embarrassing, I guess. Not as embarrassing as talking in robber-baron voice. But it worked. They got the tree dismantled and the road cleared by midnight or 1 a.m.

And in the end the whole thing, with the sidewalk repair and whatnot, only ended up costing us, like, $286 billion? I know! If you’re a homeowner you’re going, “Wow, I assumed it would be at least $400 billion.” And if you live in New York you’re like, “Interesting, a 100-year-old tree costs the same as seven minutes of my rent.”

So yeah. Long story. Tall tree. But I’m telling you this because I think this is the biggest incident I’ve ever had of something from back home disrupting a holiday.

And it’s not really much of an incident. It’s like a three on the Home Alone scale, where one is “Did I leave the TV on?” and 10 is “Did I leave my young child alone to wage guerrilla warfare against two middle-aged men in a van?”

Nevertheless, I bring it up because our story today begins with another holiday disruption. And this one … well, it’s a doozy. It involves a considerably bigger change of plans than I experienced. It changes the course of soccer on an entire continent. And it also involves some giant-ass trees falling to the ground.

This is not a soccer essay. This is the world’s most random lumber company.

2. Roger Milla on Réunion

In 1990, the Cameroonian striker Roger Milla turned 38. He’d been playing professional soccer for 20 years. He was one of the most successful players in Cameroon’s history. But he was now in his sunset years, soccer-wise, and that wasn’t just how other people saw it. That was how he saw it.

He’d spent most of his career playing in France, putting up good if not mind-blowing numbers for a succession of good if not world-beating teams. But now he’d left mainland France behind and was playing out the end of his career for a little club on the island of Réunion, in the Indian Ocean, which he loved because the scenery was gorgeous and the competition wasn’t too intense. It was like being on vacation.

Roger Milla. Not Miller, if you don’t know him. It says Miller on his birth certificate, thanks to a clerical error, but his name is Milla. Born in 1952, in Cameroon.

Cameroon. If you can picture the continent of Africa—the shape of it—well, you know how there’s that big bulge on the upper left, in the northwest? And then if you go south a little ways, the bulge kind of tucks in? There’s that sharp bend in the coastline on the western side, and right in the middle of that bend is Cameroon.

It’s a medium-sized country. About 28 million people. It was colonized by the Germans in the 19th century, and that, to borrow a term from academic historians, was a fucking nightmare. So after World War I, the League of Nations—the precursor to the United Nations—was like, we have to come up with a better solution.

So they did the only thing a high-minded organization committed to the cause of justice could do in the 1910s. They arbitrarily divided Cameroon between the British Empire and the French Empire. Values.

So part of the country speaks English, but most of it speaks French. Cameroon achieved independence, finally, in the early 1960s, but the francophone part and the anglophone part are frequently at odds. Footnote one, see colonialism.

Now, take the Google Maps image of Cameroon you’ve got in your brain and scroll it to the southeast. Right and down. You come to the east coast of Africa, and then you’re over the Indian Ocean. After 250 miles of ocean, you come to the big island of Madagascar. Keep going, pass over 600 more miles of ocean and then you come to Réunion, where Roger Milla is casually winding down his playing days.

Réunion, incidentally, is legally part of France. It’s part of the European Union, even though it’s thousands of miles from the continent of Europe.

What are you gonna do. We’ve got Alaska. Footnote two, see footnote one.

So Milla is playing for this little club called JS Saint-Pierroise. JSSP. It’s great. He’s way better than everyone else. He’s taking it easy. He’s put on weight. Plays a little tennis. Picture drinks with umbrellas, basically. He later said, “To finish my career that way seemed idyllic.”

I would like to add that as a writer, I too wish to end my career that way. Picture me dominating, like, a small weekly grocery store newsletter in paradise. I could be the weather columnist. It’s sunny and 72. I will take my paycheck in limes, thanks.

In his prime, Milla had spent—oh, gosh—15 years or so starring for the Cameroon men’s national soccer team. He played in the 1982 World Cup in Spain, Cameroon’s first World Cup. It’s really hard, in the ’80s and early ’90s, for African teams to make the World Cup, because FIFA, in its wisdom, lets only two teams from the whole continent play in the tournament. That’s exactly the number of teams that usually play in the tournament from just the United Kingdom.

So Milla’s been around. But now he’s retired from international soccer. Been retired for a couple of years.

I don’t know, 38 maybe doesn’t seem that old for a player in 2022? In the LeBron James/Tom Brady/Serena Williams/horse placenta/alkalizing dragonberry era, careers don’t end the way they used to. That’s a good thing.

It used to be like, “Oh hey, you’re 32 now? Here’s your cane and your hearing trumpet. Tell us a story, O grandfather.”

So keep in mind that in 1990, 38 is a geriatric number for an athlete. If you’re 38, you’re Methuselah. Milla is done with international soccer.

However. There’s a problem. The problem is that Cameroon is going to the 1990 World Cup, and the team looks awful. People are stressing out. Soccer is huge in Cameroon. They enter 1990 as the defending Africa Cup of Nations champion. Then they crash out of the Cup of Nations in the group stage. There’s a lot of discontent. And people are like, hmm, remember when we had Roger Milla? He was good, right?

And the thing is, a few months earlier, at the end of 1989, he’d gone back to Douala, the biggest city in Cameroon, to play in an exhibition game. And he’d looked great. He scored two goals. Everybody had fun.

An exhibition game is not the World Cup. Nevertheless.

Fast-forward to 1990, and this is the moment when Milla’s idyllic island life gets interrupted by a text from the dog sitter. Mr. Milla, a mighty tree of public opinion has fallen on the street of your happy pseudo-retirement. The fans, in other words, are clamoring for him to come back.

Now, no one on the Cameroon national team wants him to come back. The players don’t want him. The coaches don’t want him. Cameroon has this new manager, a sort of gaunt, chilly-looking Russian dude. He doesn’t want Milla.

So Milla, personality-wise—how can I put this? He has a little bit of Larry Bird in him. Obviously, he likes having a good time—he’s not playing on Réunion because he’s a ruthless disciplinarian who hates pleasure. But on the pitch, when the stakes matter, he’s a perfectionist. He’s been the best player in Cameroon most of his life. He was born in 1952, he traveled around the country a lot during his childhood because his dad worked on the railroads. Learned the game by playing barefoot with other kids, on dirt roads, sometimes with an orange or a tin can for a ball. He was so good that people nicknamed him “Pelé.” By the time he was a skinny 17-year-old, he was famous.

So he’s used to being better than everyone else. And he’s not known for being patient with his teammates.

They also have a nickname for him. That nickname is “Gaddafi.” Yes. After the Libyan dictator. The other Cameroonian players would much prefer to go to Italy for the World Cup without their ancient, prickly, washed, demanding ex-striker.

You know who did want him, though? Everyone else in Cameroon.

So the president of the country, Paul Biya—who’s still the president of Cameroon, by the way—issued a decree summoning him back to the national team.

The president of the country signed a decree compelling the coach to call him up.

Like OK. You’re at Disneyland. You’re having the time of your life. You’re three-quarters of the way through Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride when your phone buzzes. It’s a reporter from CNN informing you that Joe Biden has just delivered a nationally televised address from the Rose Garden demanding that you return to the Buffalo Wild Wings franchise you used to co-manage immediately.

3. No Country for Old Men

There is a question hanging over this essay like a Google Maps satellite over the Indian Ocean. The question is, Who is the World Cup for? To whom does it belong?

Easy answer: It’s the world’s tournament. It belongs to everyone. But that answer can’t be right, because it leaves out all the ways in which the World Cup excludes people. In which the World Cup is designed to reward some people more than others.

We talked about some of that when we talked about Kylian Mbappé and the World Cup in Russia in 2018 earlier in this series. If you’re an oil billionaire, or a European media executive, or a building magnate in a host country, or a middle-class TV viewer in an affluent nation, for that matter, the World Cup is set up to benefit you more than to benefit, say, a railroad worker in Cameroon whose son plays soccer with makeshift balls in the street.

But the cynical answer can’t be right, either. Because if you say, “Well, the whole thing is corrupt, the whole thing belongs to the cronies and autocrats,” then you’re leaving out the excitement and the entertainment and the delight that people everywhere find in the tournament.

I can’t speak, obviously, for any railroad workers in Cameroon—partly because I’m a white American writer in Pennsylvania, but mostly because it would violate the noncompete clause in my contract as the official spokesperson for railway workers in Denmark. But I would guess that soccer-loving railway workers in Cameroon might disagree that the World Cup doesn’t belong to them.

So it’s a hard question to answer in a meaningful way. Who is the World Cup for? What kind of thing is it? You look at this tournament like it’s a tree, you examine the bark, you examine the shape of the leaves, and then you go, “Uhhhh … is it a Speckled … Arctic … Gooseberry … Bush?”

At the same time, it’s a question that obviously matters a lot. Because the tournament is called the World Cup, not the Corrupt Assholes Cup. Or even the Rich Europeans And Sometimes Pelé Cup.

The point is, in 1990, Roger Milla was approximately the last person the men’s World Cup seemed to be for. Or at least the last professional male soccer player. He was African, and African teams struggled to be taken seriously at the World Cup. In 1990, no African team had ever made it to the quarterfinals of the tournament, and only one had ever reached the last 16. That, of course, was partly because so few African teams were allowed into the tournament, which created this whole stupid logical feedback loop where FIFA wouldn’t give Africa more slots because African teams didn’t do well at the tournament, but African teams didn’t do so well at the tournament in part because they had so many fewer chances to try.

Milla was also old. And the World Cup, at least on the pitch, is for young people. The World Cup is no country for old men. That’s a line from a Yeats poem, and let me tell you, Yeats was a fine poet, but he would have gotten vaporized by a modern 4-3-3. So he clearly knew what he was talking about.

4. Indomitable Lions

Roger Milla flies out to join the Cameroon team. He’s been called up by political fiat, essentially. And most of the team is not pleased about this. There are still a few players on the team who played with Milla during the ’82 World Cup, but for the most part, it’s a younger squad.

Yeats says that an old man’s heart is “sick with desire / And fastened to a dying animal.” 24-year-old midfielders are like, “Yeah, and you also suck at sports.” The kids are not happy to see Great-Grandfather Gaddafi back with the team.

And the worst part, for Milla? They’re right. He’s out of shape. He’s heavy, he’s slow, he’s labored. He looks like he’s been playing country-club tennis with, like, 64-year-old neurosurgeons named Jean-Philippe, because he has. He huffs and puffs. The kids are like, What’s the matter, old man, can’t you keep up? Wow, it’s so weird that you can’t, given that you’re twice our age, and also we exercise regularly.

But remember, the thing about Milla is that he’s got that nasty streak. That Larry Bird streak. Think about, like, Larry Bird in the ’80s. You basically could not say anything to Larry Bird in the 1980s, because any comment you made, no matter how apparently innocuous, was apt to prompt Larry Bird to devote himself body and soul to proving you wrong and sapping your will to live.

Oh hey, Mr. Bird, your shoe’s untied. Larry Bird spends the next eight months ruthlessly perfecting his shoe-tying technique. The next time he sees you his shoe knots are flawless to a degree that is psychologically devastating to anyone else with feet. And then he just stands near you—just stands there, with his perfect knots, looking down at your suddenly humiliating normal knots, and you’re like, GAAAAAAH, and he’s like, “That’s what I thought.”

Milla gets to work, in other words. Cue elaborate sports movie training montage.

This is maybe the right place to mention that Cameroon’s national soccer teams have arguably the coolest nicknames in the game.

African teams in general have great nicknames. Basically any African team’s nickname is like three times better than every non-African team’s nickname? I’m not kidding around. France’s nickname is the Blues. Italy’s nickname is the Blues. Meanwhile, Ghana is the Black Stars. Tunisia is the Eagles of Carthage. So much better.

But Cameroon’s is the best. Cameroon is the Indomitable Lions.

Good Lord, that’s a cool nickname.

The point is, in Cameroon nickname terms, the old indomitable lion is determined to show these indomitable cubs what’s up.

5. If Only Fallen Trees Could Dive Like Jürgen Klinsmann

The 1990 men’s World Cup has kind of a bad reputation in retrospect. It’s mostly deserved. The late ’80s and early ’90s were the peak of a few different trends in the game that really needed to change. And the tournament in Italy ended up being a turning point, to some extent, because it put those bad trends on full display for a billions-strong audience.

Not a lot of goals, for one thing. The 1990 World Cup saw 2.21 goals per game, still a record low. That is a deeply disturbing statistic for the purposes of this series.

This is a tournament of defensive setups. It’s a tournament of tough fouls. It’s a tournament, in short, of soccer balls flying every which way except into the backs of soccer nets.

1990. Also a ton of diving at this World Cup. Let’s be real, there’s a ton of diving at every World Cup. You learn to live with it. But 1990 was special. Just a festival of fifth-act opera deaths in the penalty area. Including the singing, in some cases.

One of my favorite dives ever took place in this tournament. In the final, West Germany played Argentina. And the great West German striker Jürgen Klinsmann, a true artisan of just absolutely unrestrained fake on-pitch agony, gets taken down by the Argentine defender Pedro Monzón.

Monzón gets a red card. And to cite the match announcer, it was a ... bad tackle.

It’s a deserved red card, probably. But watch the video and you see that Klinsmann hits the ground and gives this giant, full-bodied, writhing flop—like, imagine a melodramatic fish being electrocuted.

Here’s my favorite YouTube comment on the video of this dive: “Great lift off, wonderful rotation, nice double somersault with pike, not his best dive but should get some 9s on the board.”

1990 was also the peak of the hooliganism problem. Or at least the peak of the global media’s fascination with the hooliganism problem.

This fascination was mostly concentrated on English fans and their reputation for semi-organized violence. There were some good reasons for this. We’ll get into it another time. For now, just know that the impression many people had in 1990 was that if you had to play England, English fans in Burberry jackets were going to show up in droves looking to beat the shit out of random passersby. Sort of like the British approach to the global economy circa 1750.

Anyway, ahead of the 1990 World Cup, the British sports minister visited the Italian authorities and was like, Yeah, man, I don’t know what to tell you, it’s not great. So England ended up having to play all its group matches in a kind of quarantine situation on the island of Sardinia, where there was still a fair amount of brawling and rock-throwing and fighting with the police.

Cameroon plays its first match in Group B, not on English Fight Club Island, but at the San Siro, the storied stadium in Milan. Bad news: They are drawn against Argentina.

Argentina, the defending champions. Argentina, the team captained by Diego Maradona.

Before the match, the Cameroonian players had to endure a bunch of just gruesomely racist questions from European reporters, who wanted to know, basically, whether they ate monkeys and brought a witch doctor with them to Italy. And I know this because the Cameroonian player Francois Omam-Biyik said after the match, “We hate it when European reporters ask us if we eat monkeys and have a witch doctor.”

Incredibly, Cameroon upsets Argentina. Wins 1-0. Admittedly, they do this, largely, by kicking the living crap out of Argentina. Lot of hard fouls. Two Indomitable Lions get sent off. Cameroon finishes with nine men. But they stop Maradona and ride out the win on the back of Omam-Biyik’s 67th-minute goal. Unreal.

Roger Milla comes off the bench for the last 10 or so minutes of the game. And honestly, for a 38-year-old to hold the fort for the final 10 percent of one of the all-time World Cup upsets would be impressive enough. But Milla, and Cameroon, are just getting started.

6. Using the Butt

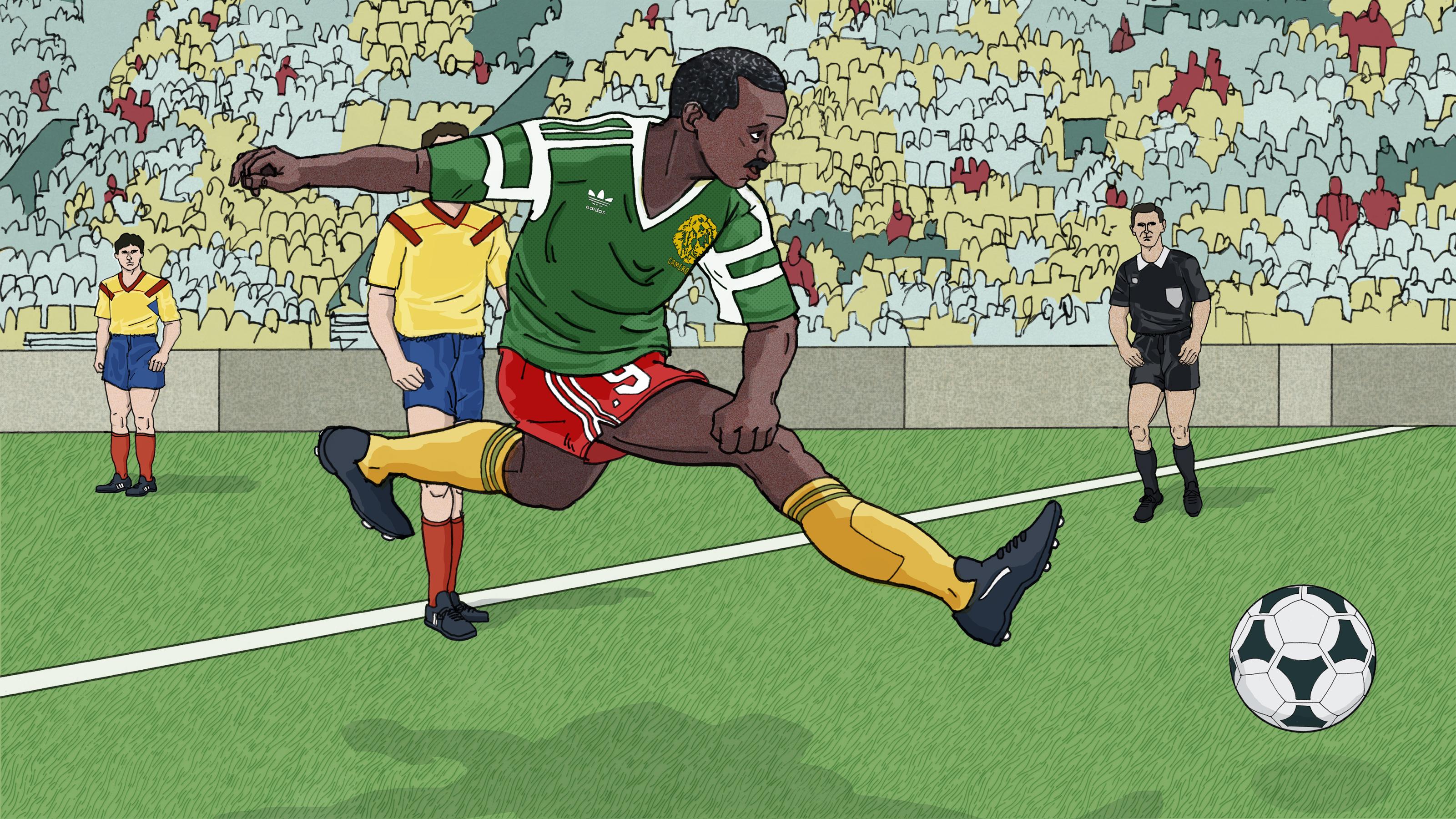

Group B, game no. 2. Indomitable Lions of Cameroon versus Romania at the Stadio San Nicola in Bari.

What’s Romania’s nickname? Let’s look it up. Oh. It’s “the Tricolors.” [Releases heavy sigh.]

I just … don’t know why it’s so hard.

People! Why don’t you just pick the coolest animal in your geographical territory and add a kick-ass adjective to it? Romania’s national animal is the lynx! Why are you not playing as the Unsurpassable Lynxes?

Alternately, you could name yourself after literally any tree, and leave me completely unable to ID your team on television.

Roger Milla starts the game on the bench. He starts every game on the bench. This time, however, he’s sent in a little earlier. He comes on in the 59th minute. Match is scoreless.

Jump ahead to 12 minutes before the end of the game. Still 0-0. Romania has probably been the better team overall, but it’s been tight.

The Cameroonian defender Jules Onana plays a long, high pass, a 70-yard pass, toward Milla. Not the type of pass you can be overly precise with. And it ends up dropping closer to the Romanian defender, Ioan Andone.

Ioan Andone. Pretty good defender in his era. He was banned for a year in 1988-89 for this incident in the ’88 Romania Cup final in which he apparently [checks notes] dropped his shorts and waved his genitals derisively at the adult son of the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu.

What?! Did that really happen?? I can’t find video evidence, for which I’m profoundly grateful. But Andone played for Dinamo Bucharest, whose big rival is a club called Steaua. Valentin Ceaușescu, the dictator’s son, was the president of Steaua. Numerous sources say that the match ended controversially and Steaua was named the winner. If your president is the son of the dictator, you tend to get the calls.

Ceaușescu denies this. I have no idea. That’s what people say.

And in protest, Andone dropped his shorts and waggled his, uh, maple tree at Ceaușescu Junior’s box. How far are you prepared to go for justice?

LONG ban from the Ceaușescus for doing that. Apparently you can be a dictator and still be a dick-hater. (Your dad texted me that joke.)

Probably worth it, for Andone? I feel like you either dine out on that story proudly for the rest of your life or you pray everyone forgets about it and never mention it again.

Anyway, the ball drops right in front of Andone. But Milla’s closing down fast. And the thing about 70-yard passes is that they have a funny tendency to bounce.

The ball hits the ground. Boings up about 15 feet in the air. Call it the boing of destiny. Milla uses the time while the ball’s in the air to catch up to Andone. They’re at the edge of the area, toward the right side. Andone jumps and Milla jumps, but Andone jumps straight up, while Milla, who’s been sprinting forward, is still moving forward in the air. And that momentum allows him to knock Andone off-balance, deflect the ball with his chest, and knock it into the center of the area.

Andone goes down. Milla hits the ground and almost falls over too—he staggers, his arms windmill; he’s about a quarter of an inch from face-planting. But he catches himself. He springs up. The ball’s now in the area, a couple of steps away. Another Romanian defender is breathing down his neck. The goalkeeper’s rushing out.

Milla gets to the ball. He smashes the shot. Boom. Back of the net. 1-0 to Cameroon. 1 billion-0 to Africa so far in this World Cup.

And now. Having scored the goal, Milla does something that becomes almost as legendary as the goal itself. He runs to the corner flag and does a little dance.

Yeats once wrote, in a poem about old age, “Seventy years have I lived, / Seventy years man and boy, / And never have I danced for joy.”

Milla’s like, yeah, fuck that. He dances for joy, in full view of the TV cameras and everyone watching.

The dance he does … I’m not going to describe it. Go look up the video. It’s mildly suggestive, I think it’s fair to say? It involves standing close to the corner flag and sensuously kind of slaloming his hips. There are people who say it’s a Makossa dance, a kind of popular dance in Cameroon, but Milla says no, he just made it up on the spot.

There’s a really funny Washington Post profile of him that was written after this match. The reporter goes to his room. He’s packing, because Cameroon have advanced in the tournament. They’re moving to a different hotel. And Milla answers the door naked, and he’s like, yeah, come in and ask me about my dance.

And he says, “In Cameroon, we dance like that. We use the butt.”

Now, obviously, I have no claim on Cameroonian dance culture. I barely have a claim on Danish railway-worker dance culture. But could I just gently request to have that line inscribed upon my tombstone?

Maybe in a small font in the corner. Like, here lies Brian Phillips, Loving Husband, Son, and Internationally Revered Soccer Podcaster. And then some tasteful blank space. And then “We use the butt” in like a classy, engraved cursive script?

It would be my honor to have it there.

The goal is an immediate global sensation. The dance is an immediate global sensation. It becomes even more of a sensation when Milla scores again 10 minutes later, this time with a driving right-footed shot from a tight angle in the area. And does the dance again. Is there shimmying? There’s shimmying. Holy shit. Cameroon is gonna win this. Cameroon does win this. 2-1, in the end.

Cameroon’s in first place in Group B. Cameroon celebrates. According to Sports Illustrated, the team dietician lifts the ban on ice cream, “whereupon midfielder Cyrille Makanaky proceeded to scarf down a pound of the stuff.”

When they lose 4-0 to the USSR in their last group game, Francois Omam-Biyik says, “We weren’t ready for the Soviet match. We were drunk, drunk, drunk.”

7. Let’s Dance

Makes no difference. They finish with the worst goal differential in Group B and still win the group. They play Colombia in the round of 16.

What’s Colombia’s nickname? It’s “the Coffee-growers.” OK, that’s … vivid? But wait. Oh my God. They’re also called “the Tricolors.” WHAT. The national animal of Colombia is the condor. I weep for humanity. Also for condor...anity.

Roger Milla comes on in the 54th minute. Match is tied 0-0 at full time. Guess what happens in extra time? Roger Milla scores twice. Two goals in two minutes. Two dances, also in two minutes.

He’s already the oldest man ever to score in a World Cup. And he keeps breaking his own record. Because that’s how time works.

Cameroon reaches the quarterfinals. It’s the first time an African team has ever made it this far in the tournament. Cameroon is drawn against—do you know? Care to hazard a wild guess?

That’s right. England. The country with the wildest and most hazardous fans in the tournament.

OK, OK, OK. In fairness, I will grudgingly acknowledge that the vast majority of England fans in 1990 were not that wild or hazardous. Minimal hazardousness from most English supporters in Italy. It’s the hazardous minority that ruins it for everyone else.

The Cameroon match is played in Naples, a city where I personally would think very carefully before I attacked any random strangers. And it goes off without any major outbreaks of violence.

In training before the match, Milla gets so intense that the other Cameroon players can’t help but laugh at him. He runs around yelling, “Play like it was the real thing!”

Kickoff. Milla comes on after halftime. He wins a penalty, which Emmanuel Kundé converts. He sets up a goal for Eugène Ekéké. Cameroon is beating England 2-1, thanks to Milla. The semifinals are in reach. They’ve felled some big trees already—Argentina, Colombia—and with 10 minutes left in the match, they’ve just about chopped down another.

But then, in the 83rd minute, Gary Lineker wins a penalty. Gary Lineker converts it. Extra time.

In extra time, Gary Lineker wins a penalty. Gary Lineker converts it. Two penalties in 22 minutes. Welcome to 22 Minutes: The Story of the World Cup, unfortunately.

Milla, and the Indomitable Lions, fall out of the tournament. But not before they’ve captured the world’s imagination. Milla’s super-sub heroics, and his dancing, are two of the indelible images, two of the joyfully indelible images, of a tournament that didn’t produce all that many of them.

Cameroon is out, but not before they’ve made a point about the potential of African soccer and its right to be taken seriously on the world stage. As Omam-Biyik had said after the Argentina win, after fielding all those racist questions about witch doctors, “We are real football players and we proved this tonight.”

8. Time, Like a Savvy Midfielder, Passes

Remember the question we asked a little while ago. The Google Maps satellite question? The question is, who is the World Cup for? Whom does it belong to?

For a few nights in the summer of 1990, it belonged, unequivocally, to a 38-year-old Cameroonian who wasn’t even supposed to play in the tournament.

And it belonged to fans in Cameroon. And fans in Africa. And any fans who were able to share in the pure happiness of Roger Milla’s dance. FIFA didn’t plan it that way, and the big soccer countries didn’t want it that way. But one of the wonderful things about the World Cup is that the people who run the tournament aren’t always the ones who write the story.

And four years later, in 1994, soccer’s sphere of belonging, its sphere of inclusion, expanded just a little bit. On the basis mostly of Cameroon’s run to the quarterfinals in 1990, Africa was finally granted a third team in the tournament.

This year, when the World Cup kicks off in Qatar, there will be five African teams in the field.

Roger Milla kept playing, longer than he ever intended to—and why wouldn’t you, if you were a hero to almost everyone who saw you play? He went to the next World Cup, in the United States, in ’94. Cameroon didn’t do as well in that tournament. They got knocked out in the group stage. But Milla came on as a substitute in the Lions’ match against Russia. And one minute after entering the match, as a 42-year-old, he got the ball in the middle of the area. He fought by two defenders and scored a goal, breaking his own record as the oldest player to score in the tournament.

Everyone on earth is getting older every second, and so you’d think Milla’s record might have been broken by now. But it’s been almost 20 years, and the record still stands. So many old soccer players in the world, but none of them have done what he did. And few players of any age have done anything to bring the world so much joy.

There’s no simple answer to the question, Who does the World Cup belong to? Except this one: It always belongs to a player who can do that.