The housewives of the Victory Project aren’t desperate, exactly, but they are a bit confused. What, they wonder, are their husbands doing all day at the office—assuming, of course, that there actually is an office located somewhere beyond their company town’s cookie-cutter suburban sprawl? Look past the roofs of the tract houses all clustered together, WandaVision style, and the landscape is bizarrely lunar. Ostensibly we’re in sunny California, but Victory might as well be on the moon.

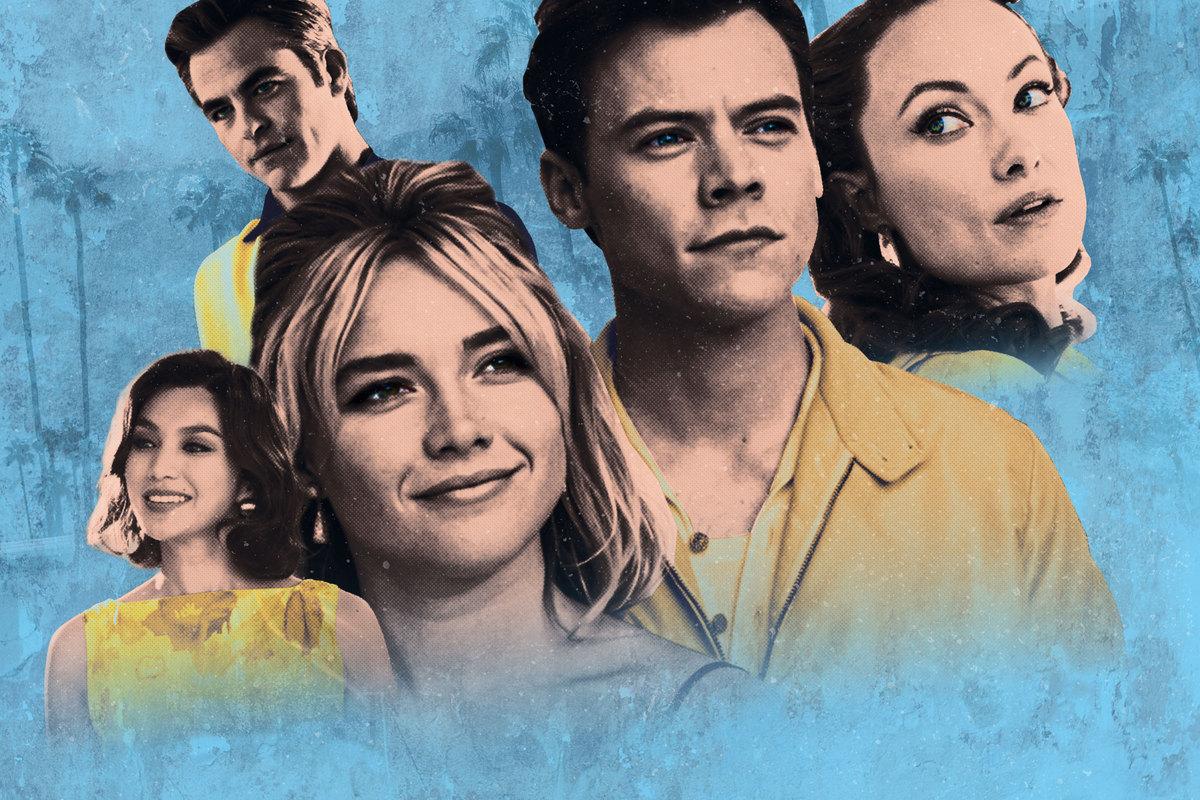

That’s why Alice (Florence Pugh) innocently asks her partner Jack (Harry Styles) to explain the high-paying job that’s subsidizing their domestic bliss. He explains, a bit haltingly, that he’s a “technical engineer”; when his wife presses him for further clarity, Jack toes the corporate line. He reiterates, a bit nervously, that he and the other suit-and-tie guys who drive off into the desert every morning and return home after dark for dinner and highballs are working toward nothing less than a better world. “I told you,” he says, “we’re developing progressive materials.”

Coming in the context of a cautionary tale about the perils of Making America Great Again, the line deserves a good, bitter laugh. Two movies into her directorial career, Olivia Wilde has made developing progressive materials into her specialty. A slick, palpably ambitious thriller drenched luxuriously (and skeptically) in retro-’50s aesthetics, Don’t Worry Darling is, at its core, a movie about the lies men tell women and why. From its deceptively placating title on down, it means to be a scathing send-up of patriarchal mind-fuckery, complete with a villain modeled on Jordan Peterson. And in mounting a fable that’s conspicuously ambiguous about time and place, Wilde is trying for a sort of surrealist social commentary, capturing a post–#MeToo mood by strategically warping the details past naturalistic or documentary truth. It’s an assignment with a high degree of difficulty—one she doesn’t pull off.

Wilde’s 2019 debut, Booksmart, was a widely acclaimed high school comedy hyped as a distaff version of Superbad; its inventory of gross-out gags, psychotropic hallucinations, and F-bombs was punctuated by righteous, politically correct politics, with adolescent-BFFs Beanie Feldstein and Kaitlyn Dever conspicuously placed on the right side (which is to say to the left) of every social or cultural issue in sight. In theory, a mainstream American comedy flaunting such progessive values is a good thing, but the overbearing generational flattery quickly wore thin. In a productively withering review for 4Columns, Melissa Anderson noted that for a supposedly chaotic coming-of-age picaresque, Booksmart unfolds in “an anodyne, frictionless world” where “nothing offensive, troubling or surprising happens,” concluding that the film “has the cut-and-paste, committee-stamped feel of a movie composed over several different iterations.”

That same description also applies, though even more damningly, to Don’t Worry Darling, which limps into theaters bearing the scars of a seriously troubled production. It’s hard to remember the last time that an American studio movie had this much of a reputation—you’d probably have to reach back 35 years to Ishtar, which was (perhaps not uncoincidentally) also directed by a quote-unquote “difficult” woman. At this point in the news cycle, it’s impossible to keep track of the multidirectional, he-said-she-said pettiness festering at every juncture of the movie’s creation; Billy Joel could easily compose a new verse of “We Didn’t Start the Fire” based solely on the chaos of the film’s Venice premiere, which culminated with a video of Harry Styles allegedly (though probably not) spitting on costar Chris Pine. For her part, Wilde has tried to downplay “baseless rumors” that she has been feuding with her leading lady; meanwhile, the only press that Pugh seems to be doing for the movie has come in the form of shade-adorned T-shirts and Aperol spritzes.

The social-media maelstrom around Don’t Worry Darling is likely to outlive the movie, but it’s not necessarily indicative of where things went wrong. The more crucial detail comes in the credits. The script is by Booksmart scribe Katie Silberman, who reputedly did a full revision of the much-hyped and duly Black Listed screenplay by siblings Carey and Shane Van Dyke (yes, descendants of ’60s-sitcom king Dick). In a good thriller, story, style, and subtext feel integrated on a molecular level. Perhaps owing to its splintered authorship, Don’t Worry Darling plays like a movie that’s pulling itself apart. It’s less pressurized than atomized, spraying images and ideas in every direction in the hopes that they’ll coalesce into something more than the sum of their influences.

The most obvious inspiration here is Ira Levin’s ingenious and ideologically loaded 1972 novel The Stepford Wives. No less than Stephen King once called Levin “the Swiss watchmaker of suspense novels,” and both The Stepford Wives and its predecessor Rosemary’s Baby pivot precisely on finely tuned suspense mechanisms. Each is told from the point of view of a modern, upwardly mobile young woman who comes to believe—correctly and heartbreakingly—that her husband has entered into a conspiracy designed to reduce her to a sort of sexual receptacle. When it first came out, The Stepford Wives was analyzed in the context of second-wave feminism, but it’s held up over time—and transcended decades of rip-offs, remakes, and parodies—because its cruelty is so lucid. The idea of men being so threatened by female autonomy that they try to replace their partners with anatomically correct sex dolls has a ruthlessly plausible misogynist logic—the Sleeping Beauty myth updated for an era of high-tech commodity fetishism.

There are no androids in Don’t Worry Darling, and no elderly Satanists either. The twist, when it comes, is much more predictable on a couple of levels—both as a capitulation to genre tropes and an attempt to self-consciously glom onto a woke zeitgeist. Wilde is nothing if not a topically minded filmmaker, and, like Jordan Peele—who cited The Stepford Wives as a big influence on Get Out—she’s committed to making a proverbial “movie of the moment.” The problem with this approach, beyond generating some of the same, self-congratulatory smugness that undermined Booksmart, is that Don’t Worry Darling spends more time ticking boxes than squeezing tension. In a recent conversation for Interview, Wilde told Maggie Gyllenhaal that making “shitty movies” helped to prepare her for the task of making good ones, and yet throughout her latest, the filmmaker keeps pratfalling over her own good intentions.

For instance: Alice’s anxiety about the nature of her picture-perfect life and what’s underneath it is aroused when she observes her neighbor Margaret (KiKi Layne) acting strangely. The rumor is that one day, Margaret wandered into the desert—a strict no-no—and lost her young son. Alice’s empathy and curiosity click in, but not in time to prevent Margaret from committing an act of spectacular self-harm. The scene in which she dies is too poorly staged to be scary, but not to disguise its unpalatable implications. Wilde’s deployment of a stoic, suffering African American woman as combination truth-teller and sacrificial lamb is the worst kind of cliché, with Layne’s character slaughtered on the altar of a white heroine’s triumphant self-actualization.

And when Don’t Worry Darling isn’t being clumsy, it’s being didactic: Where a movie like Rosemary’s Baby immerses you in a miasma of psychic unease, Wilde keeps underlining her metaphors like there’s going to be a pop quiz at the end. As she grows weary of her daily chores, Alice feels figuratively as if the walls are closing in on her, and then they literally do. The spooky, quasi-subliminal flash cuts of demonic faces and Busby Berkeley–style choreography are especially hacky—they don’t come from the character’s subconscious so much as the contemporary elevated horror playbook. As for the big, Peterson-esque speech by Jack’s boss and Victory’s CEO, Frank (Pine), who rants about remaking the world in his own alpha-male image, it’s not nearly as unsettling as Tom Cruise’s respect-the-cock shtick in Magnolia, a movie that was as ahead of the 21st-century MRA wave as Don’t Worry Darling is trying to ride it.

Pine is no Tom Cruise, but he still gives the best performance in the movie, probably because he isn’t asked to do much but look suavely sinister. Styles, meanwhile, is asked to do a lot in what is, admittedly, a pretty layered role, and a fair-minded critic might suggest that, given the overall shape of the film, the lack of chemistry between him and Pugh is not a bug, but a feature. Earlier this year, Wilde tried to stoke controversy and anticipation by saying that Don’t Worry Darling would reintroduce the idea of “female pleasure” to multiplexes, but the big dinner-table sex scene between her stars feels weirdly mechanical and choreographed—which, again, is maybe a fascinating choice given what’s actually going on in the story. In order for this material, which is all about deception and keeping up appearances, to work, there has to be a sense that both Alice and Jack are, to varying degrees of awareness, role-playing. On that note, the ambient, nagging distraction of Styles’s celebrity, exacerbated by his earnest, paltry attempts at embodying rage or desperation, generates an odd friction that probably wouldn’t have been there with a better actor.

Pugh, by contrast, is a natural: As usual, she magnetizes the camera with the best wide, staring eyes in the business. She’s suitably terrified throughout Don’t Worry Darling, but she can do only so much in what is, unfortunately, a pallid and predictable role—one considerably less complex (or funny) than what Mia Farrow had to work with in Rosemary’s Baby. Where Farrow was playing an actual character with a relatable, eccentric inner life, Pugh is playing an archetype; a hapless victim trying to see through the haze of her own gaslighting. We’re never quite aligned with her the way we were with Rosemary (or Daniel Kaluuya in Get Out). It’s more like we’re waiting for her to catch up to what we already know is going on. Wilde, who shows up on-screen as Alice’s neighbor, doesn’t degrade Pugh in her direction, but that isn’t the same thing as showcasing her gifts. What’s ironic—and dispiriting—is that a movie skewering the male urge to blandify and instrumentalize women ultimately uses its star in much the same way.

Late in the film, Alice suggests throwing a dinner party to try and trick Frank into revealing what she knows to be his ulterior motives. He’s wise to her plan, though, and tells her so, adding condescendingly that he’s been waiting for one of Victory’s trophy spouses to wake up to the reality of their situation before ultimately lamenting that Alice is a less-than-worthy adversary. “I expected so much more from you,” he smirks. It’s nice, sometimes, when movies save us the trouble and review themselves.

Adam Nayman is a film critic, teacher, and author based in Toronto; his book The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together is available now from Abrams.