All hail Paddy Considine, a true star on this first season of House of the Dragon. George R.R. Martin previously praised Considine for bringing Viserys a “tragic majesty that my book Viserys never quite achieved,” and that really came through in Episode 8. Viserys’s final speech to his family was so powerful that it almost reconciled Alicent and Rhaenyra …

Almost. The moment Viserys leaves the feast, a fight breaks out between the children, as Aemond derisively toasts his nephews. The obvious truth about Jacaerys, Lucerys, and Joffrey Velaryon can’t be unseen just because the king and his daughter won’t acknowledge it, and it’ll have big implications. Let’s look at exactly what’s underneath the surface with those three strong boys.

Deep Dive of the Week: Bastardy and Inheritance

Someone had to say it. Rhaenyra’s children are bastards, and Vaemond finally let everyone know in Episode 8, as loudly as he possibly could. For that, he lost his head, though Daemon let him keep his tongue.

Obviously, the true parentage of Rhaenyra’s children is a big deal. That’s why Rhaenyra goes to such lengths to keep it a secret, and why Viserys threatens to cut out tongues as soon as anyone questions the legitimacy of his grandchildren’s parentage. But what exactly would it mean for Rhaenyra, her sons, and the realm at large if this fact were accepted as truth? It’s time to take a closer look at just how bastardy is handled in Westeros.

The first thing to note about bastardy is that not all bastards are created equal. Rhaenyra’s boys have both a highborn mother and a highborn father. This is in contrast to a bastard who has a smallfolk parent, which in Westeros would make them “baseborn.”

For example, Game of Thrones viewers are familiar with Gendry, Robert Baratheon’s bastard, whom Robert never acknowledged and who, at the beginning of the show, is working as a blacksmith. Gendry’s mother was a member of the smallfolk, which means that even though his father is the king, he’s easy for Robert and everyone else in King’s Landing to ignore.

But in the books, Robert also has another notable bastard (well, many of them), this one with a noble-born mother in Delena Florent. The child of those two is Edric Storm, a black-haired, blue-eyed boy who resembles his father. Unlike Gendry, Edric is raised at Storm’s End and is trained by masters-at-arms and maesters as if he were a noble.

Since Jace, Luke, and Joffrey have noble parents, they’re not baseborn. This means that even if Rhaenyra and others acknowledged that Harwin Strong was their father, these boys would still be able to live in relative comfort and receive the training and skills necessary to live regal lives. Plus, they have dragons. (Perhaps they wouldn’t have been given dragons had their parentage been acknowledged at birth—we don’t know of any bastard dragonriders prior to the Dance—but at this point those dragons have flown.) There’s no universe in which these three are thrown in with the peasantry.

But all bastards—whether baseborn or highborn—carry a stigma in Westeros. It’s thought that they’re generally deceitful and untrustworthy, because their births were supposedly the products of sin and deception.

The concept of bastardy comes up extensively in the Dunk and Egg novellas (which are all delightful reads that I highly recommend). The novellas take place in the aftermath of the first Blackfyre Rebellion of 196 AC, which comes about many decades after the events of House of the Dragon, when King Aegon IV legitimizes all of his bastards—both highborn and baseborn—on his deathbed. Those bastards take the surname Blackfyre—after the Valyrian-steel sword of Aegon the Conqueror—and eventually some try to usurp the throne, leading to a long period of on-again, off-again warfare.

In one of the Dunk and Egg novellas, The Sworn Sword, Egg—who is actually a young Targaryen, gone undercover as a squire to explore Westeros—tells the knight he is following, Duncan, how he sees bastards. “Trueborn children are made in a marriage bed and blessed by the Father and the Mother, but bastards are born of lust and weakness,” Egg says. “King Aegon decreed that his bastards were not bastards, but he could not change their nature. The High Septon said all bastards are born to betrayal . . . Daemon Blackfyre, Bittersteel, even Bloodraven. Lord Rivers was more cunning than the other two, he said, but in the end he would prove himself a traitor, too. The High Septon counseled my father never to put any trust in him, nor in any other bastards, great or small.”

What Egg doesn’t know is that Dunk was born in Flea Bottom and never knew his parents. “Egg,” Dunk responds, “didn’t you ever think that I might be a bastard?”

This exchange is noteworthy because it illuminates how many in Westeros view bastards. And while in this period of Westerosi history that stigma might be particularly heightened following the bloodshed the Blackfyres have caused, it’s still something that Jace, Luke, and Joffrey all would and surely will face, as their parentage is such an open secret. Even with King Viserys, his heir Rhaenyra, and her husband Laenor all acknowledging the boys as trueborn, they still will be seen as lesser in the eyes of many in Westeros.

Let’s circle back to the Blackfyre Rebellions and Aegon IV for a moment. Bastards can be legitimized, but only by a royal decree from the king. This mechanism is also depicted in both the books and Game of Thrones, as Ramsay Bolton was at first a bastard—Ramsay Snow. At Roose Bolton’s request, King Tommen grants Ramsay a decree of legitimacy, making him a Bolton and the heir to the Dreadfort.

However, it’s not clear whether a legitimized bastard would come ahead of a trueborn child in the order of succession. In A Storm of Swords, the fresh King of the North Robb Stark wishes to legitimize his half-brother Jon Snow and name him as his heir after the “deaths” of Bran and Rickon. His mother, Catelyn, doesn’t like the idea. “Yes, Aegon the Fourth legitimized all his bastards on his deathbed. And how much pain, grief, war, and murder grew from that?” She tells her son. “I know you trust Jon. But can you trust his sons? Or their sons? The Blackfyre pretenders troubled the Targaryens for five generations, until Barristan the Bold slew the last of them on the Stepstones. If you make Jon legitimate, there is no way to turn him bastard again. Should he wed and breed, any sons you may have by Jeyne will never be safe.”

So, back to House of the Dragon. This matter of inheritance could become a major issue for Rhaenyra’s children and the realm at large. Pretend, for a moment, that Rhaenyra is crowned after the death of her father and goes on to have a long and peaceful reign as the first Queen of the Seven Kingdoms. Upon her death, the throne should pass to Jacaerys, her firstborn child. But what if her first child by Daemon—the toddler Aegon, whom we met this episode—were to press his claim on the grounds that Jacaerys is not trueborn? The result could be war.

This is the big wrinkle in the Rhaenyra bastardy question. She’s not some lord. We’re not talking about a castle, some tracts of land, or even a kingdom. We’re talking about the Iron Throne. Even if Rhaenyra openly admitted her children are Strongs, she could legitimize them when she is crowned the new Lord of the Seven Kingdoms. But she can’t strip them of the stigma of being bastards, nor can she prevent a potential succession crisis between her bastard-born children and their trueborn half siblings—or anyone else who would seek to usurp their claims to the throne. It’s a ticking time bomb—and given just how obvious it is that those boys are bastards, there’s not really any way for Rhaenyra to defuse it.

Quick Hits

The two Aegons

Yeah, Rhaenyra and Daemon really named their first son “Aegon,” even though Rhaenyra has a half-brother named Aegon. Fire & Blood tells us that Alicent took this as a slight … and that Rhaenyra intended it as one.

For clarity purposes, at this point in the story the book takes to referring to Alicent’s Aegon as “Aegon the Elder” and Rhaenyra’s as “Aegon the Younger.” We can do the same. This will also help distinguish them from the three other Aegons who have appeared by this point in Westerosi history: the Conqueror (who established the Targaryen dynasty), the Uncrowned (his grandson, who should have succeeded King Aenys but was usurped by Maegor), and another Aegon (a son of Jaehaerys and Alysanne who died three days after being born).

That brings the Aegon count to five, but we’re still some 170 years out from Thrones. By the time that series begins, there have been 11 Aegon Targaryens … and that number inflates to 12 once we learn that Jon Snow’s real name is Aegon. It’s a lot to keep track of. By comparison, keeping just two living Aegons straight doesn’t sound so bad.

Sitting the Iron Throne as hand

Otto sits on the Iron Throne this episode, becoming just the second person to do so in this series. It feels a little off to have a man who just a few episodes ago was dismissed from his position now “speaking with the king’s voice, on this and all other matters,” with Otto seemingly stressing the “all other” here. But, despite the look of it, it’s actually rather common and even expected for a king’s hand to sit on the throne while conducting business.

We first see this all the way back in A Game of Thrones, when Ned sits on the Iron Throne while Robert is out on his royal hunt. Ned hates it:

It was, as Robert had warned him, a hellishly uncomfortable chair, and never more so than now, with his shattered leg throbbing more sharply every minute. The metal beneath him had grown harder by the hour, and the fanged steel behind made it impossible to lean back. A king should never sit easy, Aegon the Conqueror had said, when he commanded his armorers to forge a great seat from the swords laid down by his enemies. Damn Aegon for his arrogance, Ned thought sullenly, and damn Robert and his hunting as well.

Tyrion also sat on the throne when he was hand. Tywin then sits on the throne during Tyrion’s trial. In the show, Cersei sits on the Iron Throne with Tommen and Myrcella while the Battle of the Blackwater rages outside, ready to drink poison should the city fall to Stannis.

That doesn’t mean that anyone can sit on the throne, however. Jaime sits on it after he kills the Mad King Aerys, something Ned thinks is out of line. And in the books Cersei has a “gold-and-crimson high seat beneath the Iron Throne” to sit on when she helps rule in Tommen’s name. Typically, it’s only the king and his hand who actually sit on the iron throne.

That makes Otto sitting on the throne—warming it, in Alicent’s words—totally in line with Westerosi customs. Anyone else doing so, however—even Viserys’s queen, Alicent, or his named heir, Rhaenyra—would be pretty scandalous.

How do dragon eggs work?

Shockingly little is known about how dragons reproduce. This is why it’s important when, in Episode 6, Rhaenyra tells Alicent that if Syrax produces another clutch of eggs, Alicent’s children can have one, so long as she accepts Rhaenyra’s proposal to betroth the children to one another. It may seem like this offer doesn’t amount to much, as you’d think the Targaryens have plenty of dragon eggs, but that isn’t always the case. Dragons don’t seem to lay eggs regularly, and their egg-laying is certainly not something that can be prompted or even predicted by humans.

So what do we know about how dragons lay eggs? Let’s start with the sex of dragons in the first place: Have you noticed that dragons tend to be the same sex as their riders? Syrax (ridden by Rhaenyra), Meleys (Rhaenys), Dreamfyre (Helaena), and Moondancer (Baela) are all said to be she-dragons, while Caraxes (Daemon), Seasmoke (Laenor), Sunfyre (Aegon the Elder), Vermax (Jacaerys), Arrax (Lucerys), and Tyraxes (Joffrey) are all described as he-dragons (or just “dragons,” in Westerosi parlance). Vhagar (Aemond) is the only dragon with a rider who doesn’t share the dragon’s sex.

Only … this all might not actually be the case. Maesters don’t actually know how to tell the sex of a dragon. Most simply assume that dragons that lay eggs must be female, while dragons that aren’t known to have laid any eggs must be male. Yet even this is in dispute, as Maester Aemon tells Sam in A Feast for Crows: “Dragons are neither male nor female, Barth saw the truth of that, but now one and now the other, as changeable as flame.” Meanwhile, Maester Gyldayn—the narrator of Fire & Blood—calls the idea that dragons change sex “too ludicrous to consider.”

Furthermore, there are only three dragons that we know for sure have laid eggs: Syrax, Dreamfyre, and a dragon simply known as the “last dragon” that won’t appear in Westeros for some time. So how do Westeros’s historians figure that these other dragons—Meleys, Moondancer, Vhagar, et al.—are female? It could be that female dragons prefer female riders, though there are a number of dragons that have had riders of both sexes (like Vhagar, who has had two female and two male riders). Plus, many of these dragon-and-rider pairings began as eggs given to infants while they were still in the cradle—and if Westeros’s best and brightest can’t determine the sex of a dragon while it’s out and about, they surely can’t do so while the dragon is still an egg. It would be an extraordinary coincidence if somehow almost all the female riders were given female eggs and the male riders male eggs.

It seems likely, then, that some of these “she-dragons” just get recorded as such by maesters out of laziness and unchallenged assumptions about what draws a rider and a dragon together. For all we know Vhagar is male and Caraxes is female. Or maybe dragons really can change their sex altogether, like clownfish.

The point is, we just know very, very little about how dragons work. So when Syrax lays a clutch of eggs, it’s a precious thing. There’s no telling when she—or he?—will lay another.

Vaemond’s family

Vaemond’s entire claim to Driftmark centers on two important arguments. The first is that Rhaenyra’s children are not actually of Velaryon blood; they’re bastards who should be disinherited. The second is that Baela and Rhaena—who clearly are of Velaryon blood—should be passed over because they are female.

In relation to the first point, especially, Vaemond stresses that he doesn’t want his family snuffed out or the island of Driftmark to pass to someone who isn’t a Velaryon. Even if Viserys had accepted that argument, though, wouldn’t Vaemond need to have kids to keep his line from going extinct anyway? Where is this guy’s family?

With Vaemond, the show has deviated a bit from Fire & Blood. In the book, Vaemond is Corlys’s nephew, not his brother. That makes Vaemond a younger man in the book, whereas in the show, the actor who portrays Vaemond (Wil Johnson) is the same age—57—as the actor who portrays Corlys (Steve Toussaint). The age gap in the book lends a bit more juice to Vaemond’s claim, since part of the succession crisis centers on Corlys (who is 76 in the books when Viserys dies) being an old man.

Also different is that in Fire & Blood, Vaemond does have children. His wife goes unnamed, but he is the father of Daeron and Daemion Velaryon. Daeron is married—to a Hazel Harte, from a house in the Stormlands—and those two have a child in Daenaera Velaryon. So Vaemond is supposed to have two sons and a granddaughter. His line in the books seems pretty secure.

In addition to that, Vaemond also has five cousins—more nephews of Corlys—in the book. Book Daemon beheads Vaemond away from King’s Landing, and those five cousins—along with Vaemond’s children—come to King’s Landing to petition Viserys over the inheritance of Driftmark. But in doing so, they question the legitimacy of Rhaenyra’s children, and—true to his word—Viserys has their tongues removed. (These five cousins become known as “the silent five.”) Daeron and Daemion don’t repeat the rumors too loudly, however—they keep their tongues.

Given all the different moving parts here—and yet another messy family tree to keep track of—it makes sense that the showrunners decided to condense this plotline for House of the Dragon. But seemingly giving Vaemond no children at all removes a lot of the momentum behind his claim. I guess he could have argued that even in his 50s, presumably, he still has time to have children (especially given some of Westeros’s wedding practices—I mean just look at Viserys). But if he’s so worried about securing the Velaryon line, you’d think he would have done something about his own line well before this succession crisis.

More Kingsguard, more twins

We get a new member of the Kingsguard this week. Or, really, two new members of the Kingsguard, as Alicent confuses Erryk Cargyll for his twin brother, Arryk. Both are members of the Kingsguard, and both will play roles going forward.

In fact, in the books, the two brothers play a larger role in some of the events we’ve already seen in King’s Landing. Arryk supposedly found Rhaenyra and Daemon together in bed, leading Viserys to exile Daemon from King’s Landing. Erryk, meanwhile, became the sworn shield of Rhaenyra after the death of Harwin Strong. So far, we’ve seen only one of these knights, but it stands to reason that both of them could play more important parts soon.

Along with Tyland and Jason Lannister, Erryk and Arryk make two sets of twins on this show. It could have been three sets of twins, as Baela and Rhaena are supposed to be twins, but it appears the show has deviated from the books to make them sisters. At any rate, with characters named Rhaenys, Rhaena, and Rhaenyra—who all appear together in this episode—this isn’t an easy series to follow when it comes to either names or faces.

How milk of the poppy works

Viserys is very sick, and the maesters in King’s Landing are giving him a lot of milk of the poppy—Westeros’s painkiller—to deal with it. Daemon and Rhaenyra don’t quite see this as a mercy, however, asking Alicent how Viserys can possibly express his wisdom while he’s on so much medication. Alicent responds that he’d be in incredible pain without it, but Daemon’s insinuation is clear: He suspects the greens are keeping Viserys in a state of semi-delirium so they can rule in his name.

So what exactly is milk of the poppy? It’s basically an opiate—hence the poppy flowers that are essential to its production. It numbs pain, induces sleep, and is addictive. It can produce vivid dreams, but also a haze that is hard to shake.

Ned drinks milk of the poppy after a horse falls on his leg in A Game of Thrones, and he sleeps for seven days straight as a result. When Joffrey questions Sansa over her father trying to usurp Joffrey’s throne, Sansa uses the milk of the poppy as a defense. “Maester Pycelle was giving him milk of the poppy,” She says. “And they say that milk of the poppy fills your head with clouds. Otherwise he would never have said it.”

So milk of the poppy is powerful stuff. So powerful, in fact, that frequently we see characters refuse it. Tyrion starts to turn it down after he’s wounded during the Battle of the Blackwater, thinking that the maesters attending him may be loyal to Cersei, and thus not have his best interests at heart. After Jaime loses his hand, he refuses milk of the poppy because he knows it will put him to sleep, and Qyburn, who is attending him, thinks he should amputate Jaime’s entire arm. Jaime wants the stump cleaned and the arm saved instead. “There will be pain,” Qyburn says.

“I’ll scream,” Jaime retorts.

“A great deal of pain.”

“I’ll scream very loudly.”

This dilemma surrounding milk of the poppy comes up time and time again in A Song of Ice and Fire. Many characters think the maesters administer the painkiller a little too liberally, but when a character is in a great deal of pain, there aren’t really any other options for relief. It’s either drink the sleep-inducing, brain-fogging, addictive opiate, or scream very loudly.

That brings us back to House of the Dragon and Viserys. As we can see in this episode, Viserys is in a lot of pain. But as we can also see, he has moments of real lucidity when he’s not on the drug. His speech to his family during the feast is clear and powerful, standing in stark contrast to the times when he’s in his bed, high on the painkiller and unable to tell Alicent from Rhaenyra. There’s probably a bit of truth to both sides here. Does Viserys need milk of the poppy to deal with his pain? Well, he’s missing half his face. But are the greens—who, being from Oldtown, have close ties to the maesters—probably administering it a bit too liberally, to keep the king bedridden? Just observe the looks of shock and fear on the faces of Alicent and Otto when Viserys appears in the throne room.

The milk of the poppy issue comes to a head at the end of this episode, when Viserys babbles on about the prince that was promised prophecy to Alicent—who interprets his words wildly differently than how he intends. This actually isn’t the first time we’ve learned of a character having their dying words corrupted by the drug.

The very first time we hear of milk of the poppy in A Song of Ice and Fire is when Grand Maester Pycelle describes administering it to Jon Arryn—Robert’s hand before Ned—when Jon was dying. “I gave the Hand the milk of the poppy, so he should not suffer,” Pycelle says. “Just before he closed his eyes for the last time, he whispered something to the king and his lady wife, a blessing for his son. The seed is strong, he said. At the end, his speech was too slurred to comprehend. Death did not come until the next morning, but Lord Jon was at peace after that. He never spoke again.”

Viserys will never speak again either. And just as milk of the poppy may have prevented Jon Arryn from relating a discovery that could have prevented war, so too may Viserys’s inability to express himself clearly in the final moments of his life lead to an enormous amount of bloodshed.

The return of Mysaria

It’s been a while since we last saw the White Worm. She was last seen helping deliver information to Otto about Daemon and Rhaenyra’s tryst on the Street of Silk. That was some 16 years ago—what’s she up to now?

Mysaria appears ever so briefly in this episode, as she receives a report from Talya, one of Alicent’s handmaidens. “It’s been quite a night at the capital, it seems,” Mysaria says to Talya, who simply responds, “Yes, my lady” before the scene is cut short.

Mysaria’s appearance in this episode raises some questions. Who is she loyal to? What are her motivations? What’s she been doing for the past 16 years? It also inspires the same questions about Talya, who is clearly more than just a servant for Alicent but also doesn’t seem so pleased to be reporting to Mysaria. We won’t be able to answer any of these questions today, but don’t forget about these two.

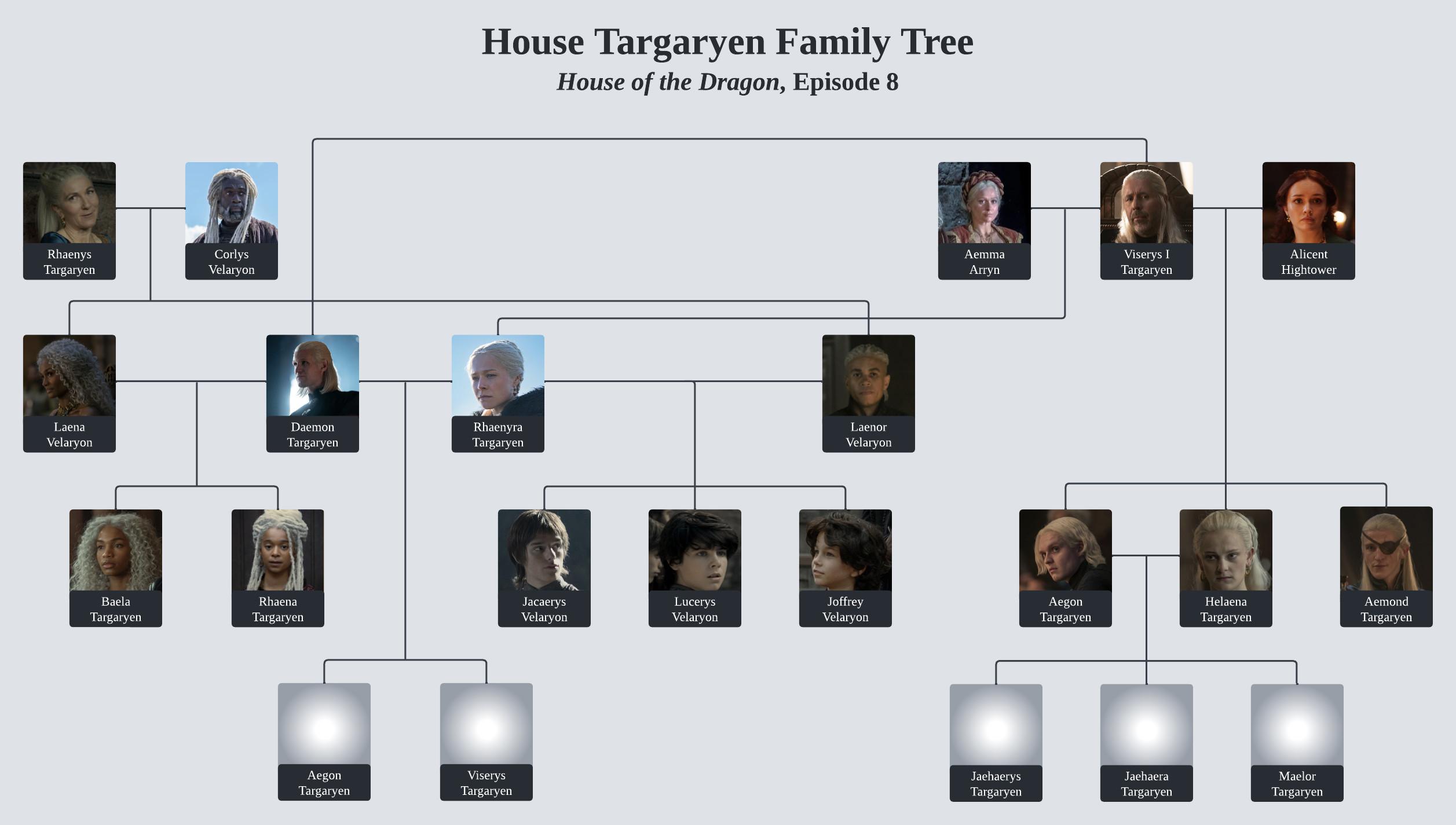

Family Tree Watch

The family tree got even more messy this week.

Rhaenyra and Daemon now have two children—sons Aegon and Viserys—with a third on the way. Aegon the Elder is now married to Helaena, and it’s mentioned that they have children. It isn’t clear exactly which kids they’ve had yet, but in the books they have three: Jaehaerys, Jaehaera, and Maelor. I’m putting all three on the chart for now.

Next Time On …

The penultimate episode of a season of Game of Thrones was often a big one. That looks to be no different for House of the Dragon. Here’s the preview for next week: