On the day before the Atlanta Braves began their postseason defense of their 2021 title, they extended one of the rookies responsible for their regular-season success. Spencer Strider, the 23-year-old righty who started the season in the bullpen, graduated to the rotation in late May, and quickly became the Braves’ most dominant starter, signed a six-year, $75 million deal with an additional team option that will keep him under team control through 2029. Strider, who had one of the most valuable non-qualified pitching seasons ever—ranking eighth all time in FanGraphs WAR among pitchers with fewer than 162 innings pitched, and fourth among those with fewer than 145—became the latest of several Braves players who’ve recently decided to stick around long term. Atlanta has locked up so much of its core that the team tops the majors in 2025 payroll commitments, with its lead in continuity and cost certainty only lengthening from there.

The eve of the division series may seem like a strange time to talk contract with a player who was already years away from free agency. But the Braves—who tied the Mets with 101 wins but squeaked past their NL East rivals with a 10-9 victory in the two teams’ season series—might not have made it this far without Strider and the rest of their strong rookie cohort, which includes outfielder Michael Harris II (who debuted on May 28 and signed his own extension in August) and infielder Vaughn Grissom, plus pitchers Bryce Elder and Dylan Lee. The Braves went 23-27 through May, but from June 1 on, with probable top-two Rookie of the Year finishers Harris and Strider starting in center and on the mound, respectively, the Braves tied the Dodgers for the majors’ most wins. The rookies’ arrivals weren’t the only reasons for Atlanta’s torrid finish, but their promotions made up for the injuries and/or underperformance of holdovers such as Adam Duvall, Ozzie Albies, Ian Anderson, Huascar Ynoa, and Mike Soroka.

Atlanta’s total of 12.4 fWAR generated by rookies led MLB and ranked 21st among all AL/NL teams since 1900. But the Braves weren’t the only team to reach this round thanks to precocious rookies: The Mariners, for one, have AL Rookie of the Year contender Julio Rodríguez, starter George Kirby, and setup men Andrés Muñoz and Matt Brash to thank for helping them snap their extended playoff drought. Before this season, the Guardians hadn’t boasted a top-10 outfield by Baseball-Reference WAR since their 10th-place finish in 2009, but they put their perennial pasture problems to rest with a fourth-place showing this season, thanks in large part to rookies Steven Kwan and Oscar Gonzalez. The Astros replaced Carlos Correa with unproven Jeremy Peña, who was 24 on Opening Day, and Peña nearly equaled Correa’s bWAR. Even Atlanta’s opponent, the Phillies, likely wouldn’t have edged out the Brewers for the third NL wild card without the five-plus WAR they got from rookie position players such as Bryson Stott, Garrett Stubbs, and Nick Maton and rookie pitchers including Bailey Falter, Andrew Bellatti, and Nick Nelson.

Although the Cardinals and their dynamic duo of Brendan Donovan and Lars Nootbaar have already been eliminated, this October is a showcase for 2022’s rookie talent—particularly its top-tier rookie talent, the likes of which haven’t been seen in a single season in living memory, if ever. This year featured six rookie position players—Rodríguez, the Orioles’ Adley Rutschman, Kwan, Harris, Peña, and Donovan—who amassed Baseball-Reference WARs of 4.0 or more. That’s two more than in any previous season. It also featured four rookie position players (Rodríguez, Rutschman, Kwan, and Harris) who reached the 5.0 bWAR threshold, another first. All in all, rookie position players hit better and produced more WAR than in any other post-19th-century season save for 2015.

No pitcher finished with four-plus bWAR; Strider easily surpassed that mark per FanGraphs, but a late-season oblique injury prevented him from reaching it at Baseball-Reference too. Even so, six four-bWAR rookies of any kind is unsurpassed since 1901 and the most in a season since 1934, and four five-bWAR rookies is tied with 1972 for the most since ’34. The best of this year’s baseball debutants played as if they’d already excelled on the sport’s biggest stage for years—and some of them are continuing to, as evidenced by Kwan’s solo homer to supply the Guardians’ only ALDS Game 1 run against Gerrit Cole on Tuesday, and the 21-year-old Rodríguez’s double and triple off 39-year-old Justin Verlander in the Astros-Mariners matchup. (Rodríguez, the fastest player ever to accumulate 25 homers and 25 steals, is only the third six-win rookie hitter of the past decade, following Mike Trout and Aaron Judge.)

One of Branch Rickey’s player-development maxims, “Out of quantity comes quality,” helps explain how 2022 became such a standout year for rookies. This season introduced us to more major leaguers than any other: An unprecedented 303 players graduated to the big leagues for the first time (pending any postseason debuts). Although the average annual tally has climbed over time—propelled by roster expansion, frequent reshuffling of bullpens, and rampant use of minor league options—this year’s total, inflated by post-lockout roster and rules changes, still represents a sizable increase over the previous record, last year’s 265. With rosters capped at 26 before September and the option-length/limit and active-pitcher restrictions that were suspended early this season now in place permanently, this year’s debut count may prove to be the high-water mark, at least until the league expands.

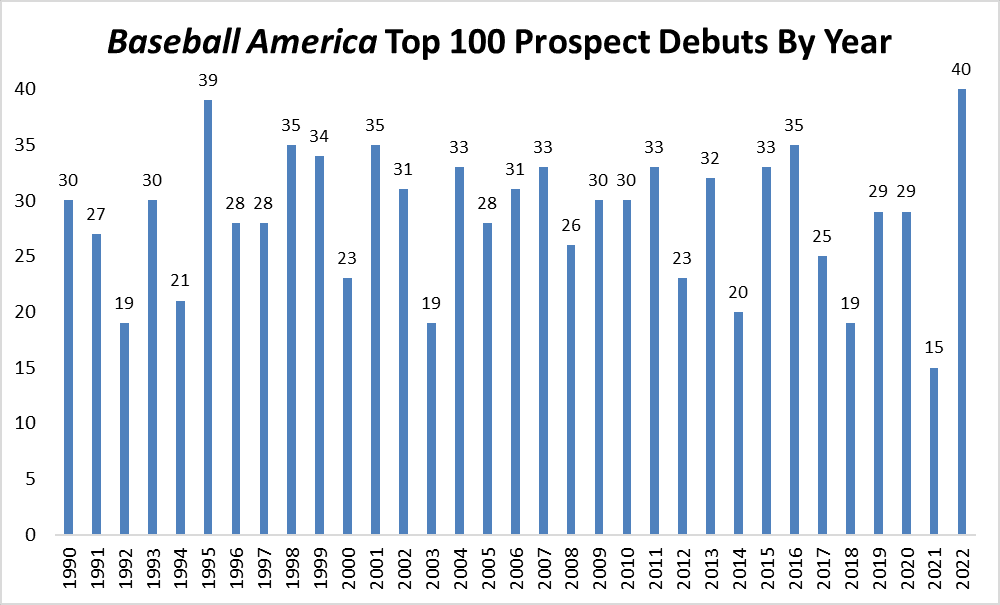

Many of those 303 were highly touted prospects. In April, I noted that more preseason top-100 prospects, as ranked by Baseball America, had made their MLB debuts within a week of Opening Day than in any season on record except 1995, when a backlog of delayed-debut prospects made the majors all at once in the wake of the 1994 strike. That trend held true all season. The last preseason-ranked prospect to arrive, Mets catcher Francisco Álvarez (who debuted on September 30), raised 2022’s total to 40, which edges out ’95’s count of 39 for the most since Baseball America’s preseason rankings started in 1990. No other year has exceeded 35.

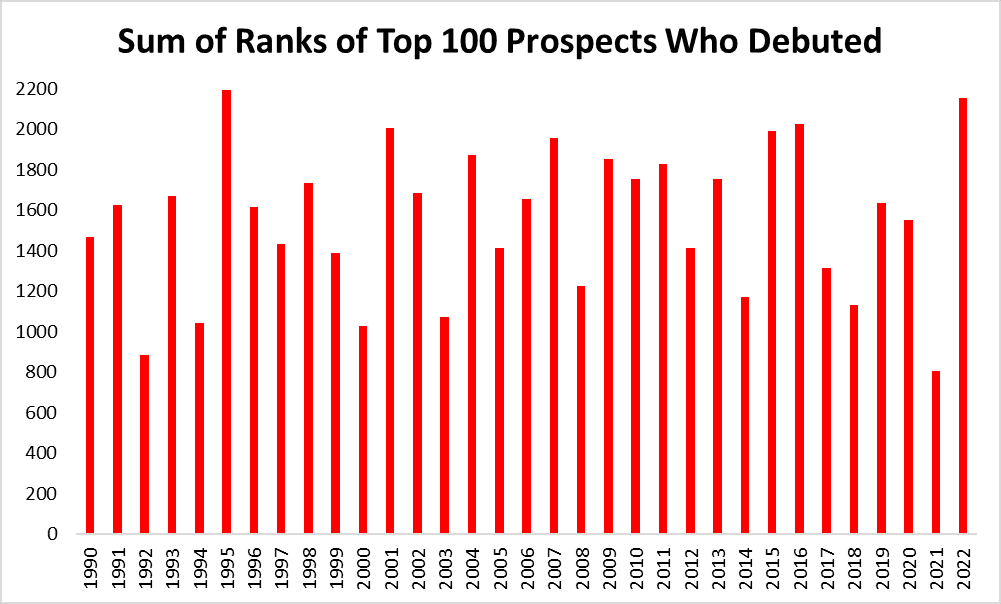

If we take into account where on the top-100 list the newly promoted players had placed, this season still looks extraordinary. The graph below adds together the ranks of the prospects who made their debuts, assigning the no. 1 prospect 99 points, the no. 2 prospect 98 points, the no. 3 prospect 97 points, and so on. This year’s sum of 2,154 places a hair behind 1995’s record of 2,191—and that’s without any contribution from Kwan, whom Baseball America omitted from its preseason list.

In short, this season brought more big league debuts than ever; more debuts by ranked prospects than ever; more star-level seasons by rookie position players than ever; and more star-level seasons by rookie hitters or pitchers than any season in a really long time. And almost all of this year’s leading impressive rookies are (or were) in the playoffs, with Rutschman the most notable exception.

Rutschman, who vied with Rodríguez in an AL Rookie of the Year race that was just as tight as the Senior Circuit’s, seemed to boost his team’s fortunes as much as the Mariners and Braves rookies: The Orioles were 16-24 before he made the majors on May 21 and 24-35 through the offensive slump he was stuck in for his 15 starts, then went 59-44 as Rutschman raked the rest of the way. Fellow O’s prospect Gunnar Henderson, who was ranked 57th on BA’s preseason list, became baseball’s top prospect (like Rutschman before him) by the time he too made the majors on August 31. Bolstered by both blue chippers, Baltimore finished only three games behind the Rays in the scrap for the third AL wild card. Their games were playoff relevant right up to the end, and their 83-win follow-up to a 52-win campaign constituted a rare turnaround.

As I observed in April, the wave of promotions on or immediately after Opening Day seemed like a response to measures in the new collective bargaining agreement that incentivized teams not to manipulate prospects’ service time. The prospect of earning extra draft picks, coupled with anti-tanking revisions to the draft lottery and the expansion of the playoff field, may have encouraged teams to—here’s a novel idea—call up prospects when they were ready to help. Although some prospects (including Henderson) may have been big league caliber before they were summoned, this season was refreshingly free of clear-cut cases of teams postponing promotions with an eye toward cost control. Instead, they generally rewarded their most promising prospects with deserved promotions and, in the process, rewarded themselves and their fans with the most competitive, entertaining teams.

Of course, we shouldn’t expect so many top prospects to appear every year; this year’s call-up spree probably cleared out the upper levels of the minors enough that next season’s crop could be lighter, especially given the smaller rosters at the start of next season compared to this year’s. Even so, it was fun to be spoiled this season by all the talent on tap—and it’s not a complete coincidence that so much of that talent is still suiting up. When the kids are this good, it pays to let them play: The Braves and Mariners put their trust in Strider and Rodríguez, respectively, on Opening Day, and they and other playoff teams who relied on great rookies early are enjoying the payoff several months later. So are we.

Thanks to Lucas Apostoleris of Baseball Prospectus for research assistance.