Every song has a story. Sometimes the details are perfunctory, signifying little. Other times, they can be revealing. That Noel Gallagher wrote “Supersonic” in 10 minutes high on cocaine tells you much of what you need to know about Oasis circa 1994, for example.

In rare cases, however, such stories can prove not only revealing, but redemptive. So it is with the story of “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life),” released 25 years ago this week by Green Day, the Oakland-based punk-rock outfit. People don’t talk about Green Day quite as much as they used to—and the discourse surrounding them is not as divisive as it once was. Which is, in some ways, to the band’s credit. By virtue of their longevity, their effervescent live show, and the lasting, Petty-esque sing-along-ability of almost everything they put out between 1991 and 2004, Green Day have secured a reputation as a reliable, relatively harmless musical institution—less maligned than Weezer, though not quite as coolly revered as the Red Hot Chili Peppers. (Or even Oasis.)

Yet Green Day remains poorly understood. In certain quarters they’re still derided as strike-breaking sellouts. Elsewhere they’re deemed corporatized beneficiaries of circumstance. Even fans don’t give them their proper due, in that we condense their legacy into but two bygone accomplishments: the release of Dookie, an album that improbably turned Green Day into the biggest band on the planet in 1994, and American Idiot, which came out 10 years later and improbably minted Green Day as the biggest band on the planet once again. Try out this little experiment. Press even a semi-serious Green Day fan to name Green Day’s most illuminating or quintessential song. Chances are they’ll reply with either “Basket Case” or “Boulevard of Broken Dreams.” They’ll do this not because these are actually Green Day’s most illuminating or quintessential songs, but because they remain psychologically in thrall to the albums that gave birth to them. Which: fair. Dookie and American Idiot are imprinted prominently on the psyches of two separate generations. After Dookie, people called Green Day the next Nirvana; in 2006, music critic Marc Spitz likened American Idiot to Elvis Presley’s 1968 comeback special. It’s rare that a band can puncture the public consciousness even one time, let alone twice, and each time in a manner so emphatic. These were albums as events; among fans, they warp our memories like victories in war.

Nevertheless, this view is incorrect. It’s also minimizing. Green Day is not a harmless musical institution. They’re not “sellouts.” And they’re not two-hit wonders. They’re one of the greatest rock bands of all time, descendants of Cobain and Strummer but also McCartney and Springsteen. Their story demands to be told in more than two parts. And “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life)” illustrates why.

Green Day released “Good Riddance” as the penultimate track off their fifth studio album, Nimrod, on October 14, 1997. The band recorded the song alongside their producer, Rob Cavallo, inside Conway Recording Studios, in East Hollywood, over the spring and summer of that year. The song’s true roots, however, like those of Green Day itself, trace back to Berkeley, California, and the DIY punk scene that germinated there during the late ’80s and early ’90s.

That scene revolves around a makeshift music venue known as 924 Gilman. Gilman was founded late in 1986 and quickly assumed a kind of religious importance to the musicians and music fans who assembled there. Billie Joe Armstrong, Green Day’s frontman and principal songwriter, was among them. He first started showing up to Gilman alongside future Green Day bassist Mike Dirnt in 1987. Both found in Gilman a kind of refuge. Armstrong—who grew up in Rodeo, a malodorous industrial town 45 minutes northeast and several tax brackets south of nearby San Francisco—dropped out of high school the day before he turned 18. Dirnt, Armstrong’s best friend, had been living in Armstrong’s mother’s garage for several years by that point. For both, Gilman became a spiritual home, less a hangout than a haven. “Gilman was my first real taste of what it was like to be a punk,” Armstrong once told Ian Winwood, a Kerrang! senior writer and the author of Smash! Green Day, the Offspring, Bad Religion, NOFX, and the ’90s Punk Explosion. “It wasn’t just about music. It was also about a community and a movement. Every single weirdo and nerd and punk around the Bay Area would be there, and it was great.”

Gilman also provided Green Day an important source of artistic tutelage. The scene heavily influenced Green Day’s style, which crystallized around a mix of “the pop melodic punk of the Ramones and the politicized early hardcore of the Dead Kennedys,” as Spitz writes in his book, Nobody Likes You: Inside the Turbulent Life, Times, and Music of Green Day. It also supported the band developmentally. Armstrong and Dirnt began playing shows at Gilman (under the moniker Sweet Children) not long after they started showing up. In 1989, Green Day released their first album, 1,039/Smoothed Out Slappy Hours, through Lookout! Records, an indie label that catered to Gilman bands. That album is a rough-hewn and unintentionally jangled effort, cheaply and quickly recorded, but it shows the promise and character of the sound the band was starting to hone—and would, with Gilman’s help, continue crafting in the years to come. By 1992, having improved drastically as musicians—the product of hours of practice every day, roguish touring, and, of course, performing night after night at Gilman—Green Day had superseded Operation Ivy as the most cherished band on the Gilman scene. Their second album, Kerplunk!, became Lookout!’s bestselling album. As label founder Larry Livermore tells me, “You can’t really separate Green Day from that scene.” There probably isn’t a Green Day without Gilman.

For as supportive as Gilman could be, however, it was also puritanical. Gilman harbored a strict anti-capitalist ethic, colored by a deep-seated distrust of major labels, whose reps Gilman punks referred to unironically as fascists. The sense was major labels were interested only in bleeding the scene dry. Capitulating to their demands; falling for their false promises; compromising your artistic integrity to increase your commercial appeal—all were seen as not only uncool, but also dangerous. Such a view has deep roots in both punk and rock culture; in 1978, rock critic Lester Bangs wrote, “The music business today still must be recognized as by definition an enemy.” Within Gilman, however, it was elevated to policy. Efforts to increase one’s popularity were rigorously policed—and, if need be, ruthlessly punished. Including by exile.

This put Green Day in a pickle. Part of the problem was the band’s growing popularity. By the time Armstrong was ready to begin writing and recording songs for Green Day’s third album—what was to become Dookie—Green Day was being rather eagerly coveted by major-label reps. (“Green Day wrote the best songs. And whoever writes the best songs wins,” Atlantic Records A&R rep Mike Gitter relays to music journalist Dan Ozzi in his book Sellout: The Major-Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore.) The more pressing issue, however, was that Green Day wanted to become popular. Or, if not to become popular per se—they wouldn’t have described it like that—they were hungry to see how far outside Berkeley their talents might take them. The band was not unsympathetic to Gilman’s political logic, and they didn’t want to compromise Gilman’s integrity by selling out to corporate interests; in later interviews, they’d decline to divulge too much information about Gilman, citing fears of “punksploitation.” But their creative aspirations transcended the punk ethos. As Armstrong once revealed to journalist John Norris, “Before I consider myself a punk rocker, I’m a songwriter.”

Thus, early in 1993, Green Day signed with Rob Cavallo at Reprise, a subsidiary of Warner Brothers Records. It had not been an easy decision. In leaving Lookout!, they were betting on themselves. The band knew that if they signed with a major and their first album or even their first single flopped, they’d be dropped. And because Gilman banned major-label acts by edict—even former major-label acts—they wouldn’t have anywhere else to go. But they thought they owed it to themselves to try. The stakes were clear. Armstrong had a year to write the best songs he could, and they had better be great: Their careers were on the line. The pressure must have been intense. As Armstrong later admitted to Rolling Stone, “It felt like a make-or-break deal.”

The stakes worked on Green Day the way pressure and heat works on carbon. Over the following year, Armstrong wrote what were not only the very best songs of Green Day’s career up to that point, but some of the greatest pop songs ever written by anyone. “She,” “Basket Case,” “Burnout”: Each is as candied and controlled as early Beatles songs, only faster and more jubilant, as if a young Paul McCartney had been given a Ritalin prescription. They also rip. Though to describe these songs as merely great or fun or even “Beatles-esque” sort of misses the point. For Green Day, what they really are is foundational, obvious culminations of a career’s worth of creative growth on top of which could be built a new career and a new paradigm.

Institutionally speaking, it was in creating these songs that Green Day really started to become Green Day. Which gets us to the crux: “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life)” is a product of this period of artistic transfiguration, as well. And look, if this strikes you as unlikely, I get it. An acoustic song as tender and pretty as Lake Merritt at dusk, “Good Riddance” feels so sonically divergent from the rest of Green Day’s catalog that it seems sort of ludicrous to categorize it as anything other than a freak creative event, representative neither of Green Day’s artistry nor their artistic appeal. But it’s all here: the melodious arrangement, mesmerically wound; the airtight hook, as efficient and unobtrusive as something written by Hemingway; the lyrics that are earnest and searching, betraying a wisdom both precocious and understated. (The line, “So make the best of this test and don’t ask why / It’s not a question but a lesson learned in time” is both surprisingly astute and endearingly earnest, searingly true to young adulthood—not unlike the line, “Am I just paranoid / Or am I just stoned?” from “Basket Case,” which might not seem all that deep, but as any self-respecting stoner will attest, gets surgically to the heart of the issue.)

Further, the timing speaks for itself. Armstrong wrote “Good Riddance” during the Dookie sessions. (He was inspired by a house party he’d attended where friends of his girlfriend were passing around an acoustic guitar.) And its characteristics are, in retrospect, exemplary of Armstrong’s writing during this time—reflections of what he’d been refining, what he was perfecting, what he was trying to prove. They’re the same ingredients that make a song like “Burnout” so immediate, or a song like “Chump” so catchy. Green Day would drift away from all this to varying degrees in later years, diluting the Dookie formula with a desire to constantly go bigger: following up one rock opera with another; following up that second rock opera with a triple album that, pretty much by necessity, consisted of materially almost universally thin. But in 1994, they’d alighted upon a sound both poignant and entirely their own. “Good Riddance” embodies, on a kind of atomic level, what made it so effective.

There’s a tactile element to this, too. Armstrong wrote all his songs on acoustic guitar at the time; as Dirnt once told Alice Cooper, “When we wake up in the middle of the night to write a song, [Armstrong] doesn’t run to his amp and plug in his guitar. He picks up an acoustic guitar and starts jamming on it.” This is why, when one goes back and listens to early versions of “Good Riddance,” especially—on which it’s just Armstrong strumming his guitar, with a faster tempo and in a different key—they get the sense that what they’re hearing really is a glimpse of Green Day at their most elemental, stripped down to the artistic essence.

According to Cavallo, the producer who was among the first to hear “Good Riddance” and who has played a crucial creative role in Green Day’s career—he’s been referred to as Green Day’s George Martin—he and the band recognized the potential of the stripped-down approach right away. “We always thought it had something,” Cavallo tells me. “All of Billie’s songs always have something, there’s always something good. [But] that one was a pretty exceptional one.”

Yet, the producer and the band left “Good Riddance” off Green Day’s major-label debut. In several ways, this was for the best. The story of “Good Riddance” would not be as rich if it ended with Green Day including the song on Dookie and finding that everybody agreed with them right away. And “Good Riddance” really wouldn’t have been a sonic fit on either Dookie or Insomniac, Green Day’s fourth album; as Cavallo put it when he and I connected over the summer, “Good Riddance” “just didn’t fit on Dookie—and it certainly didn’t fit on Insomniac.”

What’s interesting here is that Armstrong didn’t think “Good Riddance” would ever make a Green Day album. (“I didn’t think it was going to be for Green Day at all,” is how he put it.) This was more than just an aesthetic concern. It was paradoxical. Even in its early incarnations, when the song played more like an unplugged version of their typical fare, “Good Riddance” constituted something new and unusual for the band. Yet it also showcased Green Day’s more innate artistic inclinations, which were ultimately punk-agnostic. Being so vulnerable about that would have been a risk. This was, after all, the early ’90s, an era which, as Chuck Klosterman writes in The Nineties, was “not an age for the aspirant.” And so, too, was the band still a product of its genre; as Ozzi, the author of Sellout, says to me, releasing “Good Riddance” on Dookie likely would have “validated all of punk’s ire.” The suspicion heading into Dookie was that “Green Day was going to be changed into this commercial product,” Ozzi says. “[‘Good Riddance’] is probably the first real, non-punk song that they released. So I feel like that would’ve just fueled that fire even more intensely, if that’s even possible.”

As it happened, Green Day validated punk’s ire anyway. Dookie—sans “Good Riddance”—hit stores on February 1, 1994. It took until the summer—and really Woodstock ’94—for the album to turn Green Day into a household name. But the backlash from Berkeley was immediate, and went far beyond a ban from Gilman. Not content with merely disowning Green Day, Gilman repurposed them into pariahs. Kids with dyed hair tried to pick fights with Armstrong on the street. Tim Yohannan, Berkeley’s most puritanical police dog and Gilman’s unofficial godfather, villainized Green Day in the punk zine he ran, Maximum Rocknroll. On a wall inside Gilman, someone spray-painted the words “Billie Joe must die.”

In public, Green Day disguised their hurt with indignance. (“Tim Yohannan can go and suck his own dick for all I care,” Armstrong told Spin in ’94.) But it got to them. “They were 20, 21 years old at the time,” Livermore says. “And [Gilman] was their clubhouse … the place where pretty much all their friends hung out, and suddenly they weren’t welcome there anymore.”

Creatively, the impact was seismic. The best evidence is Insomniac, which came out in October 1995. As Armstrong told Rolling Stone, far from feeling newly confident about being creatively vulnerable, the band grew eager while making the record to show the world “the uglier side of what Green Day was capable of.” They succeeded. Insomniac sounds as scabrous as Armstrong seems to have hoped—furious and fast and loud, yet also glowering and dour, like a dead body dredged from a lake. It’s also very sad. Ostensibly it’s about what it’s like to be too high on methamphetamine to be able to sleep. More genuinely, it’s about what it feels like to begin to distrust both yourself and everyone around you. Track 1, “Armatage Shanks,” starts with the line, “Stranded, lost inside myself / My own worst friend and my own closest enemy.” The cover art is a collage titled “God Told Me to Skin You Alive.” The song “86” directly references the band’s excommunication from Gilman, and when Armstrong sings “What brings you around? / Did you lose something the last time you were here?” his voice turns into a sullen, bitter snarl that sounds so full of contempt it had to be pried from between his teeth.

Ultimately, Insomniac proved not only an exhibition of “how ugly” Green Day could be, but a repudiation of the idea they’d ever aspired to anything like beauty to begin with. What’s riveting about the album is how effectively the band pulls this off. (The album critics most often compare Insomniac to is Nirvana’s In Utero.) What’s sad about it is that Green Day had aspired to beauty before, as “Good Riddance” would attest. It was integral to who they had been as a band. On Insomniac, they’re obviously suppressing this side of themselves—in favor, one suspects, of the Sisyphean task of trying to prove their bona fides to Gilman’s unmovable punk gatekeepers. “They had never worried about trying to show how punk they were,” Livermore says. “Because they didn’t care. They were just great songwriters. It wasn’t until they got all that pushback from the scene that they started trying to be all hard-edged.”

Giving so much of themselves to such a task took its toll, calcifying into a kind of spiritual defeat. Halfway through the European leg of their tour for Insomniac, Green Day decided to go home, citing psychic exhaustion and creative stasis. “I became very self-conscious,” Armstrong says in an audiobook he recorded in 2021 titled Welcome to My Panic. “I couldn’t figure out where ambition and integrity met.” (Elsewhere in the audiobook, he’s even more candid: “I would never want to live that part of my life over again,” he says. “Ever.”)

It’s unclear at what point Green Day decided they needed to reconsider their creative direction, or when they decided to resuscitate what they’d suppressed after Dookie, or the extent to which Armstrong considered rerecording “Good Riddance” a means of identifying that vague metaphysical point where ambition and integrity meet. But when Green Day reconvened in Conway Recording Studios in the spring of 1997 to record Nimrod, they’d committed to expanding upon their approach and sound. Dirnt, in an interview with MTV’s John Norris, described their creative headspace heading into Nimrod thusly: “Dookie was an action. Insomniac was a reaction. Now we’re on a creative path again.”

At least that’s one way to describe it. Certain songs Green Day recorded for Nimrod sound like attempts to exorcise self-consciousness and doubt. These include “King for a Day” (a vaudevillian romp about a cross-dressing drag queen buoyed by a breakneck brass ensemble), “Last Ride In” (a downtempo surf instrumental with bongos), and “Hitchin’ a Ride,” a chugging heavy metal song featuring a Middle Eastern fiddle. As Jason Lipshutz, the senior director of music at Billboard who has interviewed Green Day several times, puts it, “Almost every song on [Nimrod] is an experiment.”

Green Day seems to have conducted all of these experiments with conviction and care. Into none, however, did they invest more care than “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life).” This may have been because of what the song had come to represent for them. Remember when Armstrong told MTV’s John Norris that, before he was a punk rocker, he was a songwriter? That was for an interview the band recorded in Conway after they had played Norris “Good Riddance” for the first time. (“Will fans understand it?” a stunned Norris asked, after the song ended. Armstrong was quick in his reply, three years in the making. “I don’t give a shit. I get it.”)

That conviction had taken time to crystallize. The version of “Good Riddance” Green Day played for Norris was very different from the one Armstrong had brought with him into the studio months earlier. In the intervening months, the song had been labored over. If this was not for what the song represented to the band, exactly, it was at least for what the boys seemed to recognize it could one day become; Cavallo, by this point, was taking the “Good Riddance” demo home with him each night and listening to it over and over. “It was sort of like a musical problem to work out,” he says. “I just was playing it at my house thinking, ‘Jesus Christ, this song is a freaking hit. It just seems so close to a hit.’”

Two of the changes that Cavallo and the band made to “Good Riddance” stand out. The first had to do with the opening riff and the strummed chords underlying the first verse. One day, Cavallo suggested Armstrong try picking them, instead of strumming. This was so “the strumming would be a bookend, [like] the drums coming in or something,” Cavallo says. It worked. “The picking in the beginning was a way of creating the guitar to have two levels to it,” Cavallo says. “The guitar became a rhythm instrument subsequently after we started to strum it.”

The second big decision was to add strings. The strings were essential, though achieving the right orchestral balance—such that they accentuated Armstrong’s guitar and vocals rather than overpowered them—was painstaking. “At first [we had] a whole orchestra in there, and they’d all come in like, ‘SHUNG!,’” Armstrong said in Kerrang! “In the studio we played it as a big, Bon Jovi–style ballad. Now that was funny.”

Eventually they settled on a quartet with double bass. It took a while, however, for Armstrong and Cavallo to find the truest use of these new sounds. One day, after what must have seemed like endless vacillation, Cavallo convinced Armstrong to give him one more solitary crack at it. He sent him and Dirnt and Tré Cool, Green Day’s drummer, outside to play foosball. Within 20 minutes, Cavallo had it. He opened a window that overlooked the foosball table and asked the boys from above, “You guys want to hear a no. 1 hit?”

That “Good Riddance” might now become a hit, however, exacerbated what was for Armstrong the initial and still more terrifying issue: the song’s paradoxical, polarizing potential. Now it constituted an even wilder divergence from their established sound—and represented an even more vulnerable snapshot of Armstrong as a songwriter. They’d done away with any pretense, embellished the prettiness, increased the honesty. As Chuck Klosterman put it to me in an email, “Good Riddance” was now not just a “softer, slower version of their usual music. It was totally divorced from that—acoustic, real fragile. There are strings on [it], like it’s ‘Beth’ or ‘Eleanor Rigby,’ or something. A pretty massive step in a very different direction.” To Armstrong, the prospect of releasing this version of “Good Riddance”—in the wake of how vicious and personal the blowback to Dookie had been—must have felt as nerve-racking as waltzing naked down Telegraph Avenue blaring his old Beatles tapes through a blow horn.

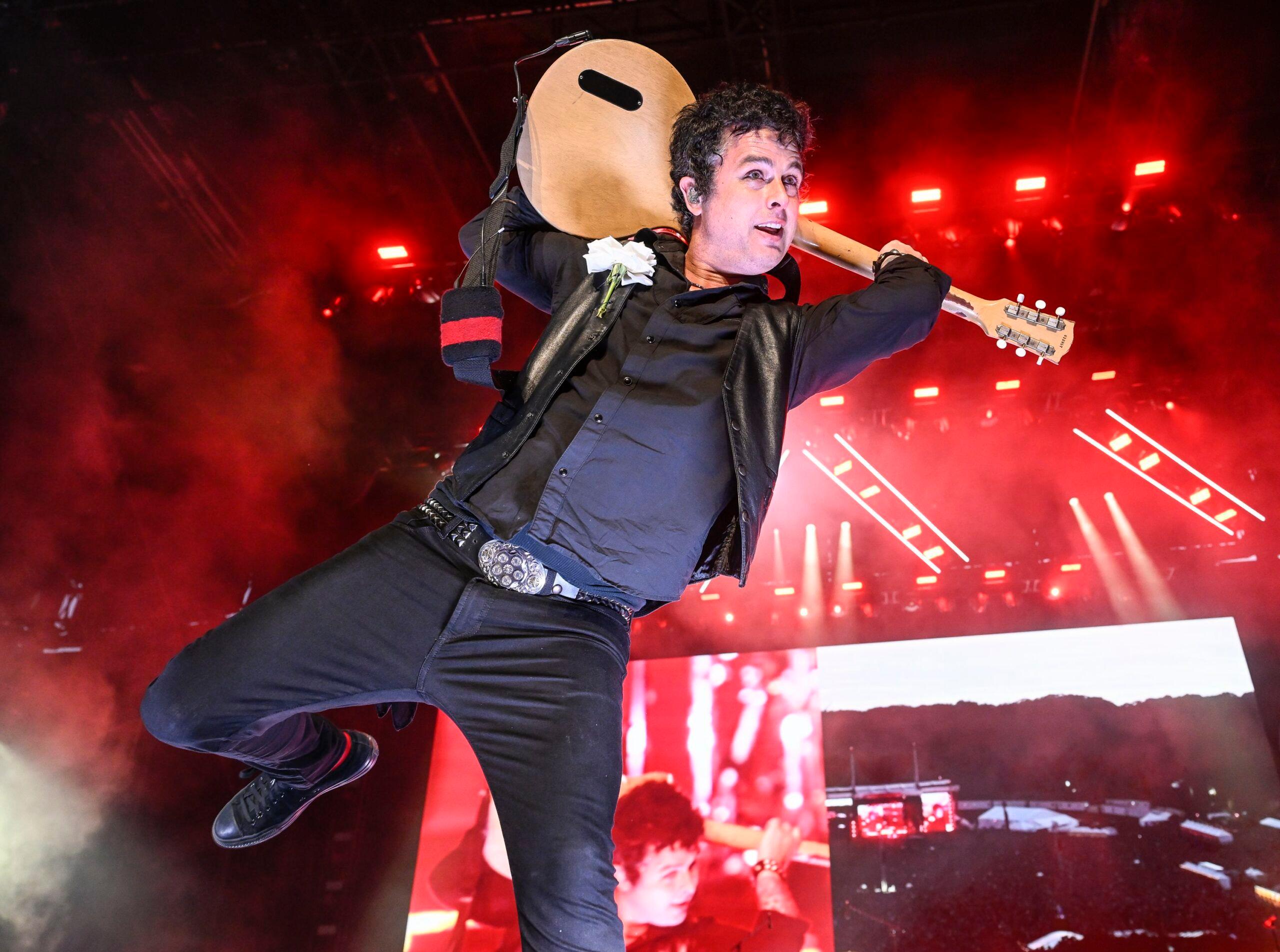

Such nerves stayed with Armstrong even after Green Day released Nimrod in the fall of ’97. The first time he played “Good Riddance” live, he had to chug several beers before going on stage. “I was scared for that song to come out,” he told Spitz. “I thought it was a powerful song and it made me cry and all that. … But because it was such a vulnerable song, to put that song out and it was like, which way will it end up going?” It was, in a way, yet another make-or-break moment.

Of course, we know which way it went. In the weeks and months following Nimrod’s release in the fall of 1997, “Good Riddance” didn’t quite go no. 1—it peaked at no. 11—but it resonated with listeners in a way that transcends the pop charts, becoming a permanent fixture in fans’ lives. It soundtracked episodes of ER and Friends, the 1998 FIFA World Cup, the PGA Tour, the Chicago Bulls’ 1999 banner ceremony, MTV’s 1998 New Year’s Eve telecast—a drunk Armstrong performed “Good Riddance” as the last song of the night, and he fucked it up, but for the moment, the fuck-up also made it somehow perfect—and the final episode of Seinfeld, which was viewed by some 58 million people. “Good Riddance” also graced an untold number of funerals, graduation ceremonies, prom dances, and, inappropriately, given the song’s subject matter, weddings. (The lyrical inspiration for “Good Riddance” was an ex-girlfriend of Armstrong who’d decided to leave both Armstrong and Berkeley in favor of a small town in Ecuador; the line “Tattoos of memories and dead skin on trial” is direct memoir: Armstrong had tattooed her name on his arm, and subsequently had to cover it up.) The song became so big that a good number of the people who heard it—while watching golf or suffering through a sibling’s middle school graduation ceremony—didn’t even know it was a Green Day song. It escaped its context.

At which point it began to become a kind of generational conduit—the Green Day song your grandma can hum, a song soccer moms loved, and, as Atlantic culture writer and Green Day fan Spencer Kornhaber says to me, a song that was “a galactically big deal to many ’90s kids, music that opened our brains to some notion of an adult world.”

What was the effect of all this? For one thing, to an extent somewhat imperceptible at the time but obvious in retrospect, “Good Riddance” changed the way people who think seriously about music thought about Green Day. This is in large part for the manner in which “Good Riddance” helped the band wriggle out of their reputation as one-note power-chord thrashers. (“This music is a long way from Green Day’s apprenticeship at the Gilman Street punk clubs,” critic Greg Kot wrote in Rolling Stone.) But it also has to do with the way “Good Riddance” augmented how people thought of Armstrong. “I don’t think a lot of people consider Billie Joe when it kind of comes to, like, the great rock frontmen,” says Billboard’s Lipshutz. “But he can kind of do it all. And I think when we’re talking about ‘Good Riddance,’ it’s a good demonstration of his range. He can put together this really sort of sweet sing-along ballad and it doesn’t sound cloying or overly cutesy, it’s just … really effective.”

“It shows how great and important a songwriter and a singer Billie Joe is,” Cavallo, the producer, said. “He wrote this song when he was probably 21 years old, maybe 19. … It’s a little tough, but it’s also written so eloquently. … Without a doubt if it’s not the no. 1, it’s in the top three of the most important Green Day songs.”

Releasing “Good Riddance” had a more practical impact on Green Day themselves: It vindicated their instincts, which liberated them creatively, and paved the way for all that would come after. As Armstrong relayed to podcaster Krissy Teegerstrom, he’d had “no intention of starting any kind of acoustic thing with Green Day.” As he’d later tell Rolling Stone, however, actually releasing “Good Riddance” changed his thinking. “It was amazing,” he said. “It opened up a brand-new world: ‘Oh, fuck, we can do so much more.’” This new sense of possibility would first lead to Warning, Green Day’s even more sonically daring and criminally underrated sixth album. Eventually, it would lead to American Idiot. As Armstrong once told writer Tom Lanham, it was during the studio sessions that produced “Good Riddance” that Green Day first toyed around with the idea of writing a rock opera. This is more telling than it may seem. In addition to an important point of cultural undeniability, American Idiot will also probably maintain in the public imagination as a kind of shocking reinvention—something no one could have seen coming. This, however, is not what American Idiot actually is. American Idiot is the culmination of an effort undertaken by Green Day years earlier. This was an effort not to reinvent but to recapture themselves. And it began, in many ways, with “Good Riddance.” All the Gilman drama culminated in it; the rock operas call back to it.

Though even this is not all “Good Riddance” represents. As Livermore says, “Something like ‘Good Riddance’ has been in gestation all of [Armstrong’s] life.” For Green Day, the painful process of embracing the song rendered out of an inchoate and self-conscious desire to make good music a more refined and unrepentant conception of what that entailed. What the song really represents is Armstrong’s reconciliation with the facts of his ambition. “Good Riddance” was always a Green Day song. And perhaps Green Day really started becoming Green Day only once Armstrong came around to that notion.

“Good Riddance” changed everything for Green Day. It delivered them from the guilt and self-doubt they’d been haunted by since leaving Gilman. It endeared them to a broader swath of fans in a new way. It helped them transform from curiosity to canonical. It’s foundational to their legacy. The legacy of the song itself, however—what makes its story truly worth telling—is that it is simply a great song. In various informal surveys I’ve conducted over the past few months, many people who insist that they’re not Green Day fans admitted openly to loving “Good Riddance.” Fellow fans, meanwhile, reference “Good Riddance” with the sort of reverence you reserve for the memory of a first kiss. There’s something so intimate and articulate about it; every time you listen to it, it’s like Armstrong’s playing it right across from you.

The song is also honest, which is another reason it was embraced. “It’s such a natural song,” Winwood, of Kerrang!, tells me. “If there had been something calculated about it, like it was their attempt to knowingly secure a giant radio hit, for example, you can usually tell these things. ... I think really no matter what you do, if you do it naturally and you do it well I think it stops becoming a surprise quite quickly.” “It sounds like a song that has always been written,” is how Kornhaber puts it. “Like that anecdote about Paul McCartney being convinced he was ripping off ‘Yesterday’ from some old show tune—it must have been like that for BJA and the gang. When I was a kid I had no clue what the words meant ... and had no conception of the regret or wistfulness or whatever that Armstrong’s singing about ... but it’s just so potent.”

That potency is a product of all that went into making it. And it’s also what makes “Good Riddance” such a powerful point of connection between Armstrong and the public. It has always felt less like a performative creation than a kind of metaphysical extension of Armstrong himself, something you’re not impressed by so much as you’re intuitively grateful for. “I had this experience at Madison Square Garden, probably 10 or 12 years ago,” Livermore, the Lookout! founder, tells me. He was watching Green Day’s set from somewhere behind the stage. At the end of the set, Armstrong started playing “Good Riddance.” “He got to the part where he brought out his acoustic guitar,” Livermore said, “and it was like the room, this 20,000-seat arena, shrunk down to a tiny space. It still takes my breath away to remember how that felt. How it was just like magic, how he could just do that. It was as if there were about five or 10 of us sitting around a campfire, and he said, ‘Hey guys, I’m going to play this song.’ And everybody, 20,000 people, are just mesmerized, as if they were all sitting right next to him, listening to him play this song. And I don’t know what you call that. It’s like, well, musicians ultimately are magicians when they can do stuff like that.”

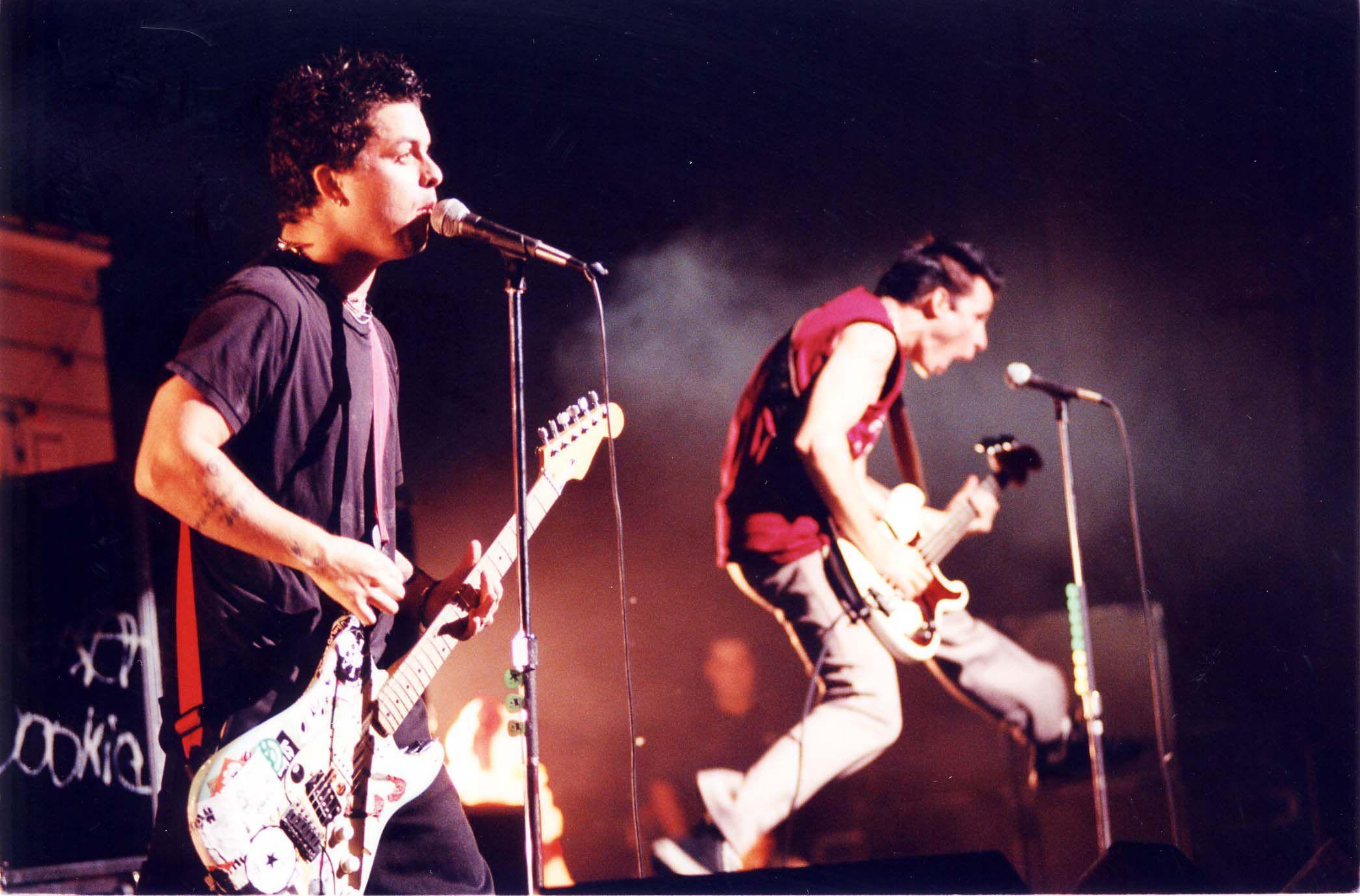

This still happens. I witnessed it just a few months ago, at Outside Lands in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Green Day headlined. “Good Riddance,” as always, was the song Green Day closed out their set with. The night was clear and warm; smoke from the stage abstracted the sky. As one can by this point likely guess, I had staked out a spot at the front of the crowd.

In case you haven’t been, Green Day shows are bombastically loud. (It was reported on this night that residents 4 miles away in Cow Hollow could hear Green Day’s set.) This is an important detail, because the loudness of the preceding two hours made the sudden quiet stillness that enveloped the stage at the end of the night—after Armstrong and Co. had ripped through the combustive penultimate encore of “Jesus of Suburbia,” and after the stage lights had dimmed, and after Dirnt and Trè had left the stage, and finally Armstrong stepped forward, alone, just him and his acoustic guitar out there before some 75,000 people in the twilight—arresting and transportive and surreal. When Armstrong spoke into the mic, and then picked those first few familiar chords, it was as if the propulsive distortion suddenly inverted and pulled you involuntarily physically closer, into some different shared space that Armstrong had created for you. This, in the parlance of the industry, is what it feels like to reside in a performer’s palm; it’s the magic trick. Though in the moment, the feeling was more symbiotic, like you were in there with Armstrong, and he was enjoying the whole thing just as much as we were.

And this struck me, suddenly, as maybe the song’s whole point. Another paradoxical reason “Good Riddance” remains easy to overlook is that it’s so culturally ubiquitous. By now, “Good Riddance” has soundtracked so many graduations and proms and sitcom finales that it feels less like an interesting piece of intellectual property than some anonymous part of the public domain. That false start; the invocation of yet another turning point; the intonation of Armstrong’s famously bittersweet “fuck you” that’ll probably still hit listeners in the gut 25 years from now—these things belong to everyone. But this is only because of how seamlessly “Good Riddance” invites you to co-opt its sentiments as your own. Which is something I guess you could say about most every great and popular song ever made, but it’s enlightening to be reminded of it in person. And as Armstrong sang that night, it was impossible not to remember. Not to recall your own bittersweet goodbyes, and your own nascent efforts to make the best of what tests those goodbyes presented. Not to be swept up and transposed the second those first notes rang out and Armstrong’s voice echoed off the eucalyptus: For what it’s worth, it was worth all the while. Understanding and in agreement, everybody sang along.

Dan Moore is a contributor for Oaklandside Magazine and The San Francisco Chronicle. Follow him on Twitter @Dmowriter or at www.danmoorewriter.com.