The Mythical Majesty of ‘Masterpiece Theatre’

The PBS series was long one of the sole purveyors of British TV in the U.S. But even as streamers and other broadcasters have gotten in on the action, ‘Masterpiece’ remains an essential part of American TV culture.One hundred years ago this week, the company that would become known as the British Broadcasting Corporation was founded in London. Transmitting news and entertainment across radio and television, the BBC would go on to have a far-reaching impact on not only the United Kingdom, but also audiences worldwide. To mark the anniversary, The Ringer is celebrating one of the BBC’s chief exports to the United States: British TV. From Masterpiece Theatre to Love Island, join us as we look back on some of the iconic shows that have crossed the pond in the past century.

When Hugh Laurie visited Washington, D.C., in January 1991, for a reception honoring the Public Broadcasting Service, “we felt there was a bit of a buzz in the air,” the actor recalls. Masterpiece Theatre, the program that delivered quality British television to U.S. screens, was turning 20 years old, and “PBS celebrated with a dinner in the U.S. State Department,” says Laurie, who at the time was a 31-year-old goofball whose comedic series, ITV’s Jeeves and Wooster, was a Masterpiece pick on American TV.

It was an exciting, proud night for internationally minded patrons of the arts. Beloved Masterpiece host Alistair Cooke was among those in attendance. The whole thing was black tie. Pairs of British actors were scattered at tables decorated with props related to their performances. But that wasn’t the real reason for the rather charged atmosphere, Laurie says.

“It was,” he thinks, “the night before the United Nations deadline ran out just before the first Gulf War. So Washington was quite an exciting place to be on that particular night. … A lot of people [were] whispering into the cuff of their tuxedos and making signs at each other.” The next day, the Masterpiece contingent got a White House tour “while [George H.W.] Bush sat in the Oval Office,” he says. “I suppose they were deliberating whether or not they were going to go ahead with this crazy scheme,” by which he means Operation Desert Storm. He switches briefly into an American accent to announce, with an affable flick of his hand, “You crazy guys!”

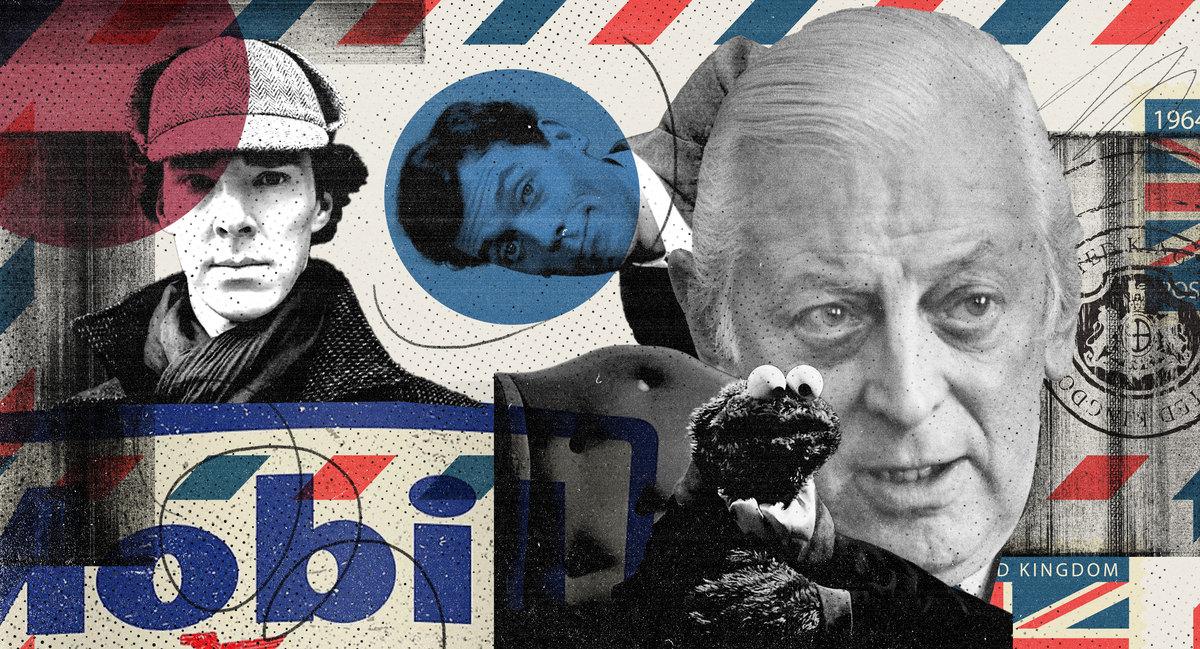

To hear Laurie recall the memory feels itself like a scene out of a British TV show: the wry recollection, the framing of one’s personal story against a backdrop of sweeping geopolitical stakes, the marked contrast in goings-on behind and in front of any given wall. It also serves as a fitting reminder of what Masterpiece has been for more than half a century. Since its start in 1971, Masterpiece has introduced American audiences to literary adaptations, twisty mysteries, and original family sagas. It has served as a launching pad for some of the most acclaimed actors around the globe—from Helen Mirren to Benedict Cumberbatch. And it has done so by being a constant presence amid the world’s perpetual tumult, a diplomatic mission with costume dramas as its lingua franca and droll comedians as its emissaries.

The story of Masterpiece begins, as so many classic American tales do, with a guy living by the fake-it-till-you-make-it creed. In 1970, public relations impresario Herb Schmertz—sort of the Don Draper of Mobil oil—got a call from Stan Calderwood, then the president of the Boston-based public TV station WGBH, to ask if he’d been watching a British miniseries called The Forsyte Saga, which had been airing on American public television. Calderwood had noticed some attention around the show, and he had also realized that the price tag of licensing something like that for American audiences was rather achievable, particularly for a going concern of Mobil’s size: $390,000 for 39 hours worth of BBC programming.

“Now, in those days—and I suppose the same holds true today—even those people who didn’t watch serious drama on public television would usually say that they did,” Schmertz later wrote, accurately, in his 1986 book Good-Bye to the Low Profile: The Art of Creative Confrontation. “So although I had never seen a single episode, I assured Stan Calderwood that The Forsyte Saga was one of my favorite shows.”

The rest is history: With an initial million-dollar investment, Mobil oil became the founding and longtime corporate sponsor of what was christened Masterpiece Theatre, a weekly program(me) that would import televised dramas from across the pond. Everything quickly fell into place: a WGBH producer knew just the right theme song for the show, having vacationed at a Club Med with his wife years earlier where at mealtimes they played the trumpet-led “Fanfare for the King’s Supper” by J.J. Mouret. Cooke was convinced to be the host, a role he’d serve for the next 21 years. The inaugural season of programming included a series about Winston Churchill’s ancestors.

The sponsorship was, of course, advantageous for the oil corporation in a number of ways, “far more than that nice warm feeling of having done the right thing,” Schmertz wrote. He listed some of the benefits in his book: “Employee morale, the enhanced visibility of top leadership, recruiting, and projecting the image of a responsible and active corporation that is concerned with excellence.” (And concerned with the bottom line: “There’s no question that our dollar goes much further in England,” he wrote. “Among other considerations, the English entertainment industry has less powerful unions, lower salaries, and a more work-oriented spirit.”)

For WGBH, the most ambitious member of the then-fledgling national public television system PBS, the benefits of such a partnership were obvious: stability, visibility, and the money, honey. But over the next decade, it became a point of public humor that Masterpiece was made possible by fossil fuels. The columnist George Will quipped in 1977 that he wanted “the hearse bearing my remains to burial to be powered on Mobil gasoline, as thanks for Mobil’s support of Masterpiece Theatre.” In her book Making Masterpiece, the show’s longtime producer, Rebecca Eaton, wrote that by the 1980s, “PBS had been known to some as Petroleum Broadcasting System, a phrase coined by a journalist because Texaco, Chevron, Gulf, Exxon, and ARCO had been pouring money into PBS programming.”

In addition to adaptations of literary works like Vanity Fair and Madame Bovary, the first decades of Masterpiece Theatre featured lively Agatha Christie stories, a BBC adaptation of the brooding Poldark novels, and five seasons of Upstairs Downstairs, a show comparing and contrasting the lives of an aristocratic British family in the early 1900s with the happenings of the large staff of servants living down below. If that description of Upstairs Downstairs sounds a bit like Downton Abbey, another program set at the turn of the 20th century that would become one of pop culture’s biggest six-seasons-and-two-movie sensations of the 21st century, that’s what Eaton originally thought, too.

Eaton was first approached about the Julian Fellowes–led Downton Abbey by a producer at the British network ITV who was seeking Masterpiece coproduction money to round out funding for the project. As Eaton wrote in the prologue to her memoir, she listened to the pitch and thought it “sounds a lot like a combination of Edith Wharton’s The Buccaneers, which we’d already done in 1995, and Upstairs Downstairs, of which we’d aired 68 episodes from 1971 to 1975, and which we’re about to remake with the BBC. Does Masterpiece really need another aristocratic-family-charming-servant miniseries at this point? Probably not.”

Susanne Simpson, then a WGBH producer who had been personally recruited by Eaton to move from the station’s science and documentary division over to the Masterpiece unit, begged to differ. “Rebecca turned it down twice,” says Simpson, who succeeded Eaton as the executive producer of Masterpiece in 2019, in a Zoom conversation. “She turned it down twice!” But when Simpson screened the first episode, she felt it had all the qualities of, well, a masterpiece. “I remember turning to [Eaton] and saying, you know, our audience will absolutely love this show,” Simpson says. “I didn’t think it was going to be the breakout hit that it was, but I thought our audience would love it because of the setting, the costumes, the beautiful actors.” She told her mentor: “If she didn’t buy this, I was gonna quit,” Simpson says, laughing. “And she bought it!”

When Simpson left the PBS series NOVA in 2007 to join Eaton on Masterpiece Theatre, the latter show was in the midst of a midlife crisis. Five years earlier, in 2002, Mobil (then ExxonMobil) had announced the phase-out of its sponsorship of the program, the end of an era. Eaton set out to find a new brand partner, thinking it wouldn’t take long to secure a commitment on the scale of $10 million a year. Instead, years passed and “I couldn’t get a lunch date,” she wrote in her book. “The absolute nadir in the search for a munificent, culturally savvy, corporate Medici came,” she wrote, “when I learned that we might have interest from the company that made Botox.” In 2008, Masterpiece Theatre was rebranded as Masterpiece and categorized into three verticals of sorts: Masterpiece Classic, Masterpiece Mystery!, and Masterpiece Contemporary.

In the years that followed, the program would go from nadir to apex, airing two shows in particular that would elevate its stature in a new way. Simpson had just finished a script-writing class when she took on her new role, so she was particularly blown away by the qualities of the scripts she was handed to read at PBS. “I remember a couple of early scripts that I read,” she says. One was for an adaptation of Emma by Sandy Welch, which stuck out because Welch had also recently done a version of Jane Eyre that was Simpson’s new favorite Masterpiece offering. “And the other script I remember from that early time,” she says, “was Sherlock.”

Sherlock, the this-side-of-caustic BBC procedural starring Martin Freeman and the then-lesser-known Benedict Cumberbatch, debuted on the Alan Cumming–hosted Masterpiece Mystery! in the United States in October 2010, a few months after its premiere on British television. In January 2011, just about 20 years after Laurie and Co. once wandered around the White House to celebrate Masterpiece’s 20th birthday, Downton Abbey arrived on American airwaves, too, introduced to audiences by Laura Linney.

With the lag in airing between British and American TV, PBS executives had an early inkling that the series would be well-received. (When Downton’s viewership went up in between its first and second episodes in the U.K., which rarely happens, they knew they had a winner on their hands.) Still, they didn’t quite foresee the scope: viewership in the double-digit millions, an endless appetite for more and more. The Masterpiece team was small, relatively speaking, and was suddenly working around-the-clock, fielding media requests and trying to keep up with exploding and highly engaged fan bases. “I mean, we’re talking, you know, 24/7,” Simpson says.

Sherlock, a spin on the Sir Arthur Conan Doyle stories that was set in the modern day, featured a snarky take on its title subject that was perfectly captured by Cumberbatch, who at the time was a shaggy-haired theater actor with only a few screen credits to his name. The show not only became a hit, it drew in a younger audience that hadn’t previously been Masterpiece viewers. So thoroughly did it launch Cumberbatch’s career that he’s now a sequel-having lead Marvel actor who has also received two Oscar nominations and been the villain in a Star Trek film. And he’s not the only one.

Before Laurie was House, M.D., he was Wooster. Before Daniel Radcliffe was Harry Potter, he acted in a two-part BBC production of David Copperfield that also starred Maggie Smith and ran on PBS in 1999. Before she was the queen on The Crown, Claire Foy played Amy Dorrit in the BBC’s Little Dorrit, another Masterpiece selection. Before Helen Mirren was a household name, she was Jane Tennison, the gruff, tough lead detective in the Emmy-winning Prime Suspect, later seasons of which were coproduced by WGBH. And before Smith was the Dowager Countess of our hearts, she was a Masterpiece fixture for decades.

The same goes for a good percentage of actors in Downton Abbey. “I know the cast loved it,” Simpson says. “Many of them were unknowns, they came to the United States, they were mobbed, they couldn’t go anywhere without having a selfie.” (The only actors who could escape the craze were the ones who played Mrs. Hughes and Mrs. Patmore, because they looked so different in person.)

By Downton’s Season 2 finale in 2012, its American ratings (around 5.4 million) were rivaling that of a successful Ken Burns documentary. At the show’s height, during its Season 4 premiere, the series drew 16.2 million viewers and became not just content, but a tentpole, the kind seated at the Emmys alongside behemoths like Mad Men, Breaking Bad, and Game of Thrones despite having a fraction of the funding. And speaking of funding, it was during the summer between seasons 1 and 2 of Downton Abbey that PBS finally found the new corporate sponsor it had been seeking: Viking River Cruises. These days, you can even book a cruise itinerary that includes a trip to Highclere Castle, where Downton (and Jeeves and Wooster!) was filmed.

Simpson knew that Downton hit different when she started seeing it get roasted. “Jimmy Fallon did a takeoff on it called ‘Downton Sixbey,’” Simpson said. “And there was a social media video coming around to the music of the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, all about Downton Abbey. I thought, wow, you know, now it’s part of pop culture.”

The same once happened with Masterpiece Theatre writ large. Alistair Cooke, the original host, often liked to joke that he’d be best and most remembered as his muppet alter ego, Alistair Cookie, on the recurring Sesame Street segment “Monsterpiece Theatre.” Played by the legendary puppeteer Frank Oz beginning in 1978, Alistair Cookie was Cookie Monster in a smoking jacket and ascot, sitting in a parlor chair. He said things like “me digress” and introduced children to parodies like “Me, Claudius” and “The Taming of the Shoe” and somehow slipped esoteric barbs in about playwrights like Spalding Gray—excuse me, Spalding Monster—along the way. He wasn’t the only one to lampoon the PBS program; others included George Plimpton on Disney’s “Mousterpiece Theatre,” and Jamie Foxx alone was part of two different skits—one on In Living Color with David Alan Grier, and another on a variety show—that played off the familiar format.

These days, Masterpiece has evolved from that iteration of itself, just as the entertainment landscape that surrounds it has. For its earliest years—really, its earliest decades—Masterpiece was not only the key curator of British television for American audiences, it was basically the sole pipeline, too. But now, with an alphabet soup of streaming options and VPNs, viewers have direct access to all sorts of foreign programming, from not only the British Empire but beyond. And increasingly, domestic networks and streamers have realized the interest audiences have in stories about Liverpudlians, or lovelorn Jane Austen characters, or bright young queens. The Shonda Rhimes show Bridgerton was a recent major Netflix original hit.

Still, Masterpiece has remained a welcome home abroad for a number of highly esteemed series, like ITV’s ongoing buddy-clergy show Grantchester, or Victoria, the retelling of the life of a young Queen Victoria that stars the popular actress Jenna Coleman from Doctor Who and was a success among younger audiences. Broadcasts this season have also included Guilt, set in Scotland, and Van der Valk, based in Amsterdam. For many years, the team at Masterpiece devoted much of its time to sifting through untold hours of already-finished productions from abroad to select the best of the best. These days, with so much competition and so little left unseen, the series seeks to get involved in the development of shows earlier and earlier, sometimes weighing in on early scripts or even initiating ideas.

Much like the people and the nation that it has long celebrated and showcased, Masterpiece has a deep-seated knack for keeping calm and carrying on—across wars and royal weddings, through shifting pop culture tastes and ever-changing presidential administrations. In 2013, Simpson and Eaton and the Downton Abbey cast were invited to the White House, not for an official state dinner on the eve of a war, but instead because a resident superfan wanted to meet them. “Michelle Obama told us that Downton Abbey was a favorite show of her family and her staff,” Simpson says, “and that they used to get hamburgers, french fries, and milkshakes to sit down and watch the episodes.” Even as British television filled the room, there was still a little bit of Americana in the house.