‘House of the Dragon’ Episode 10 Breakdown: Dragon Roll Call

A spoiler-free deep dive into “The Black Queen,” featuring a rundown of riderless dragons, dragon accidents, songs, banners, the unwritten rules of kinslaying, and more

With Rhaenyra pursuing her claim to the throne and Aemond killing his nephew, the first dragons have danced and the civil war for the Iron Throne is officially on. Before winter comes and the long night between seasons begins, let’s break down “The Black Queen,” House of the Dragon’s Season 1 finale, and consider some implications for Season 2:

Deep Dive of the Week: The Crucial Riderless Dragons

At the black council, Daemon rattles off the count of dragons. The greens have four: Aegon’s Sunfyre, a relatively young dragon who hatched shortly after the newly crowned king’s birth; Helaena’s Dreamfyre, a roughly century-old dragon who was once the mount of Rhaena Targaryen and whom Helaena doesn’t fly often; Aemond’s Vhagar, the massive instrument of war who dates back to Aegon’s Conquest; and Daeron’s Tessarion, another young dragon (we haven’t yet met Daeron, the youngest son of Alicent and Viserys; showrunner Ryan Condal confirmed he exists in the show, though he was mum on whether he’ll appear in Season 2).

The blacks have quite a few more dragons. The most important are Daemon’s Caraxes, the experienced Blood Wyrm who has accompanied both Daemon and his uncle Aemon before him in various battles; Rhaenys’s Meleys, the swift Red Queen who was previously the mount of her aunt Alyssa; and Rhaenyra’s own Syrax, the youngest of the three, and a dragon who has never seen battle.

Next up are Rhaenyra’s sons. All three ride dragons who hatched when the Velaryon boys were infants. Jacaerys rides Vermax, Lucerys rides Arrax (but not for long), and Joffrey rides Tyraxes. Daemon’s daughter Baela also has a dragon, Moondancer, which is also young, as in Fire & Blood Baela hasn’t yet ridden her dragon when the Dance breaks out.

The blacks also hold Driftmark and Dragonstone—where many unclaimed dragons reside. Laenor’s dragon, Seasmoke, resides on Dragonstone (answering the question of whether Seasmoke traveled with Laenor to Essos, but leaving unresolved whether a dragon will accept a second rider while another is still alive). Then there are Vermithor and Silverwing, the former mounts of King Jaehaerys and Queen Alysanne. They reside near the Dragonmont, as do three wild dragons: Sheepstealer, Grey Ghost, and Cannibal.

“But who is to ride them?” Rhaenyra asks. Daemon ignores that question, shifting the conversation to his idea to take Harrenhal and establish a foothold in the crucial, centrally located Riverlands.

We shouldn’t move on so quickly, however. Dragons are the ultimate power in Westeros, and mounting these unclaimed dragons would give the blacks 13 dragons to the greens’ four. Even accounting for the fact that the blacks don’t have a dragon anywhere near as ferocious or intimidating as Vhagar (Daemon’s Caraxes being the closest), that’s a power imbalance that the greens would be unlikely to overcome. Getting these dragons battle-ready should be a high priority for the blacks.

And so it is that we see Daemon dipping out of a subsequent black council meeting to head deep into the Dragonmont and sing in High Valyrian to a dragon that Condal has confirmed is Vermithor. Let’s go over the backgrounds of these dragons, as they’ll certainly play a crucial role in the war to follow.

We’ll start with Vermithor. Remember Jaehaerys, the old king at the beginning of the series who preceded Viserys? Vermithor was his dragon, a “great bronze and tan beast” that had hatched from an egg placed in Jaehaerys’s cradle when he was an infant.

Jaehaerys had a long and storied reign as king, and Vermithor was with him throughout. When Jaehaerys’s reign was still in its regency, the king frequently rode Vermithor to and from Dragonstone, where he married his sister Alysanne in secret. When he came of age and took power in King’s Landing, Vermithor took him even farther. Jaehaerys made it a point to visit as much of his kingdom as he could, and unlike Aegon the Conqueror, who traveled in great processions, Jaehaerys took small hosts with him so that he could swiftly travel the continent and visit smaller castles. “I do not need to ring myself about with swords so long as I ride Vermithor,” the king says in Fire & Blood. In time, Jaehaerys visited virtually every region of Westeros, save Dorne, on Vermithor’s back.

By the time of House of the Dragon, Vermithor is roughly 100 years old, not ancient for a dragon—though he hasn’t been ridden in some 30 years. In that time, he’s made a home for himself on Dragonstone, like so many other riderless dragons. Vermithor is the second-largest dragon in the realm, behind only Vhagar, but unlike Vhagar he has almost no battle experience. Jaehaerys’s reign was so peaceful that Vermithor was used as a weapon of war just once, when Jaehaerys burned the Dornish fleet during the Fourth Dornish War. That conflict lasted only a single night before the Dornish surrendered.

Still, Vermithor is big, and size is a priority given how young and small the blacks’ other dragons are. And although Otto rattles off a list of the symbols of legitimacy belonging to Aegon II—his name, his crown, his sword, his throne, etc.—Vermithor offers the blacks plenty of legitimacy if they can claim him. Jaehaerys was the realm’s longest-ruling and most beloved king, and even 30 years after the Conciliator’s passing, there are surely many in King’s Landing who remember Vermithor.

Next up is Silverwing, another century-old dragon a bit like Vermithor. Queen Alysanne’s silver she-dragon hatched from an egg that was placed in Alysanne’s cradle, and soon became Alysanne’s mount. Like Vermithor, Silverwing spent much of her time shuttling her royal rider around Westeros. Alysanne even made it up to the Wall—though Silverwing refused to take Alysanne any farther north, a development that deeply troubled the queen.

Silverwing is about the same age as Vermithor, and is therefore presumably one of the largest dragons in the realm. But like Vermithor, she lacks experience—Silverwing wasn’t present for the Fourth Dornish War, and we have no record of her taking part in any kind of combat to this point. Fire & Blood goes on to describe the dragon as “docile.”

On to Seasmoke, who comes with questions. No known dragon has ever taken a second rider while another lives. But no known dragonrider has ever abandoned a dragon, either. We’re in uncharted territory when it comes to A Song of Ice and Fire lore here.

Seasmoke is a young dragon of about 30 years old, but at least has some experience in battle, as he helped Laenor, Daemon, and Corlys defeat the Triarchy way back in Episode 3.

While it’s unclear who could possibly ride these dragons—just as no known dragon has had two simultaneously living riders, no known rider has ever had two dragons (or even taken a second dragon after a first mount died)—at least these dragons are familiar with being ridden. The next three dragons Daemon mentions are wild—dragons who have never had a rider. Let’s look at what we know about them.

First up is Sheepstealer, who lives on Dragonstone and is named for self-evident reasons: He loves to steal sheep. Sheepstealer hatched when Jaehaerys was “still young,” making the mud-brown dragon up to 100 years old by the time of the Dance—though given how little we know about even bonded dragons, we should leave open the possibility that wild dragons grow at different rates than those that are bonded and live around humans.

Next is Grey Ghost, who is so named because of his shyness; he avoids being seen by humans for years at a time. As such, we know basically nothing about him, other than that he prefers a diet of fish caught from the Narrow Sea. I can at least report the color of this dragon: gray.

Finally, there is Cannibal, so named because he’s known to feast on dragon corpses and dragon eggs. Cannibal is an old, large, black dragon who lives on Dragonstone. Some smallfolk claim that Cannibal has been on Dragonstone since before the arrival of the Targaryens, but this seems unlikely, as the Targs first arrived on the island some 240 years before the start of the Dance of the Dragons. Balerion the Black Dread is the only dragon known to have died of old age, and he died at around the age of 208 (the exact year of his birth isn’t known with certainty, though the range of possibilities is relatively slim). It’s simply hard to believe that Cannibal is decades older than the oldest-known dragon, even if the idea of his being descended from a different group of dragons could explain why he’s so antagonistic to the Targaryen-descended dragons.

The last thing to know about Cannibal is that he is particularly mean, even for a dragon. Fire & Blood tells us that “would-be dragontamers had made attempts to ride him a dozen times; his lair was littered with their bones.”

That covers all the dragons referenced at the black council. (Daemon also mentions a clutch of eggs that he has, though even if those were to hatch immediately, they would not be ready for battle for years.) There are a few more dragons in the realm, however. Daemon fails to mention that his son Aegon the Younger has a dragon named Stormcloud who is also far too young to deploy in battle. Their other son, Viserys, is in possession of only an egg. Similarly, Aegon II and Helaena’s young children Jaehaerys and Jaehaera have dragons—Shrykos and Morghul—who also must be too young to ride. Their youngest child, Maelor, should also have an egg.

This brings us back around to the big question: How will the blacks find riders for these dragons? It’s thought that Targaryen blood—or at least Valyrian blood—is necessary to bond with dragons, as no one outside of House Targaryen has ever ridden a dragon in Westeros. To that end, Targaryens have lived in Westeros for more than 200 years, arriving at Dragonstone shortly before the Doom of Valyria. And as we see from so many of these noble houses, the Targaryens are no strangers to siring bastards (Aegon II already has some, as shown in Episode 9). These bastards are known as “dragonseeds,” and many smallfolk living on Dragonstone claim to have the blood of the dragon flowing through their veins. Whether these dragonseeds will be able to claim dragons, though, remains to be seen. And even if they are able to claim dragons, can the blacks trust them?

These are questions for Season 2. For now, the blacks have many more dragons than the greens, but the dragons they have largely lack battle experience, and many are either riderless or so small as to serve little use in battle (something Lucerys and Arrax found out this week).

Quick Hits

The danger in trying to control dragons

In Game of Thrones, there are many scenes in which Daenerys doesn’t have the greatest control over her dragons. When she’s occupying Meereen in Season 4, Drogon’s tendency to kill and eat sheep causes issues with Meereen’s shepherds. And when Drogon kills a young girl, Dany decides to chain her dragons away in the pits of Meereen—though she does so only with Rhaegal and Viserion, as Drogon remains at large in the countryside.

For a long time, fans of A Song of Ice and Fire had a few explanations for Daenerys’s struggles. One is that she is the first person to have dragons in more than a century; any secrets to taming and controlling them have been lost to history. Another is that she has three dragons, and we’ve never seen a single person tasked with controlling so many before. Yet another reason is that Daenerys’s age ranges between 14 and 16 in the books; she’s basically a child herself. So it makes sense that she would have a particularly hard time corralling her dragons.

House of the Dragon is showing us that those explanations are unnecessary, as there is another one: Dragons just aren’t made to be controlled, period. Viserys says as much early in the series, telling teenage Rhaenyra that “the idea that we control the dragons is an illusion” and that “dragons are a power that men never should have trifled with.” In this week’s episode, we see how wrong it can go when a Targaryen trusts that he has control over his dragon; Arrax attacks Vhagar against Lucerys’s wishes, and Vhagar kills Arrax and Luke against Aemond’s wishes.

In Fire & Blood, there’s no indication that Aemond’s killing of Lucerys is an accident. Aemond takes off after his nephew when one of Lord Borros’s daughters taunts him. (“Was it one of your eyes he took, or one of your balls?” she says. “I am so glad you chose my sister. I want a husband with all his parts.”) The fight takes place so close to Storm’s End that guards on the castle walls can see the sky light up in streaks of flame as the two dragons grapple with each other—there is no extended chase scene that sees them fly far from the castle or ascend above the clouds.

This deviation from the books could be explained as something that’s just not recorded in Westerosi history. It’s not like Aemond can just say that this was all a big misunderstanding—he kind of has to own his role as Lucerys’s killer now, whether he wanted that honor or not.

And while House of the Dragon is really hammering home this idea that dragons are intelligent but wild beasts that can never truly be tamed, there are hints of this in A Song of Ice and Fire lore as well. In 54 AC, a 12-year-old Aerea Targaryen (King Jaehaerys’s niece) claimed Balerion the Black Dread and disappeared into the sky. She went unseen for more than a year, and Jaehaerys told his small council something that echoes Viserys’s quote above: “Balerion is a willful beast, and not one to be trifled with. To leap upon his back, never having flown before, and take him up … not to fly about the castle, no, but out across the water … like as not he threw her off, poor girl, and she lies now at the bottom of the narrow sea.”

But Jaehaerys was wrong, as Aerea did return—on the brink of death. She was thin as a rail, her skin was burning hot, and “there were things inside her, living things, moving and twisting, mayhaps searching for a way out.” The maesters tried to help her, but nothing worked. Her skin started to burn and crack, until steam and smoke came out of her nostrils and her eyes burst as if boiled, and she soon died. It was then that Septon Barth deduced that Balerion—who himself had returned with some new deep scars and wounds—had taken Aerea to Old Valyria. Barth ruminates on this: “From the very start we have asked, Where did Aerea take Balerion? We should have been asking, Where did Balerion take Aerea?” He reasons that Aerea never would have gone willingly, but that she didn’t have the ability to steer Balerion elsewhere.

In short: Dragons have minds of their own. And as mentioned above, the blacks are on the verge of putting into motion a plan to find new riders for their riderless dragons—including some dragons that are openly described as “wild.” Surely nothing can go wrong there, right?

The taboo of kinslaying

Aemond’s accidental killing of Lucerys will start a war the likes of which Westeros has never seen. And because Luke was his nephew, it could also brand Aemond for life as a kinslayer.

Kinslaying is one of Westeros’s greatest taboos. It’s actually largely why the Dance of the Dragons doesn’t burst into bloodshed the moment Rhaenyra learns that Aegon II is crowned. In Fire & Blood, Rhaenyra mentions this in the black council:

Her first act as queen was to declare Ser Otto Hightower and Queen Alicent traitors and rebels. “As for my half-brothers and my sweet sister, Helaena,” she announced, “they have been led astray by the counsel of evil men. Let them come to Dragonstone, bend the knee, and ask my forgiveness, and I shall gladly spare their lives and take them back into my heart, for they are of my own blood, and no man or woman is as accursed as the kinslayer.”

Kinslaying is notable for being universally reviled in Westeros. Even people who have a more distinct culture from the rest of the continent—such as the Iron Islanders or the wildings north of the Wall—mention kinslaying as a great sin. But like everything in George R.R. Martin’s fictional universe, kinslaying comes with layers of complexity. There are degrees to kinslaying—killing a distant cousin during a war isn’t seen as nearly as bad as slaying a sibling or a parent in cold blood.

For example, when Robert Baratheon rebels against the throne prior to the events of A Game of Thrones, he famously kills Rhaegar Targaryen at the Battle of the Trident. Robert and Rhaegar were second cousins (Robert’s grandmother was Rhaelle Targaryen), which would make him a kinslayer. Only … no character ever mentions this, as Robert and Rhaegar weren’t closely related and they were on opposite sides of a war (and no one wants to call the new king a kinslayer).

Similarly, when Rickard Karstark kills a couple of captive Lannisters in retaliation for Catelyn Stark’s release of Jaime Lannister, Robb Stark declares Rickard a traitor and sentences him to death. Rickard says that killing him will make Robb a kinslayer, but this is a stretch—the Karstarks are a cadet branch of the Stark family, but they split off from the main Stark family tree roughly 1,000 years ago. No one takes Rickard’s accusations of kinslaying seriously, and Robb beheads him.

On the other hand, some of the more egregious kinslayers in A Song of Ice and Fire aren’t likely to get off so easily. Stannis has his brother murdered (unless you believe Melisandre was acting on her own) and is shielded by the fact that few understand how Renly died. Tyrion kills his father, Tywin, but hasn’t returned to Westeros since (and everyone already thinks he slew Joffrey, making him a double kinslayer in the eyes of many). And Ramsay Bolton murdered his father, Roose, in Game of Thrones, which he weakly excused by claiming that Roose was “poisoned by our enemies.”

Aemond falls somewhere in the middle. Lucerys was only Aemond’s half nephew, and while there was no open warfare yet between the greens and the blacks, the conflict was starting to take shape. He’ll definitely face some stigma as a kinslayer. But how much remains to be seen.

The painted table

The painted table lights up now, how fun! It seems that if you’re going to plan a conquest of Westeros, this is the place to do it. Thrones fans will remember Stannis preparing his war here in Season 2 (and doing more than that with the table), as well as Daenerys plotting her conquest in Season 7. The table was originally commissioned by Aegon the Conqueror before his conquest of Westeros, and was famously painted without any borders to symbolize Aegon’s intention to unite the continent. It’s also the place where Aegon died, due to a stroke suffered in 37 AC as he was telling his grandsons about his conquest.

Circling back to Otto’s point about the importance of symbolism, that Rhaenyra sits on Dragonstone and plans her war from the very place that Aegon the Conqueror planned his is notable. It lends her quest to earn the throne some weight. Plus, the big map helps with the literal planning of the conflict. Daemon says that “as an instrument of conquest, our army leaves a lot to be desired,” but the same can’t be said for the actual room they’re in. That place was made specifically for conquest.

The green three-headed dragon

The Kingsguard knight Ser Erryk Cargyll interrupts one of the black councils to inform Rhaenyra that a galleon “flying a banner of a three-headed green dragon” is approaching Dragonstone. It’s Otto, arriving with his terms for peace.

This is a bit odd, because Otto should really be flying a black banner with a red dragon on it—you know, the sigil of House Targaryen. Given how much he harps on the value of symbols of legitimacy, changing Aegon II’s banner from that of Aegon the Conqueror to something else would be very strange. Perhaps this is some kind of personal banner for Otto, but that too would be odd—he’s coming on behalf of the king, so it would make the most sense for him to fly the king’s banners.

Of course, Rhaenyra will also want to fly the banner of House Targaryen. In a civil war, this can get confusing rather quickly, so the solution is that one or both sides of the conflict will need to change their banners. Both sides actually do this in Fire & Blood, though neither adopts a green dragon—this may be a change for the show, much like how the show has embraced green as an official color of House Hightower, while in the books its sigil is white and gray, and green is just a color Alicent is fond of.

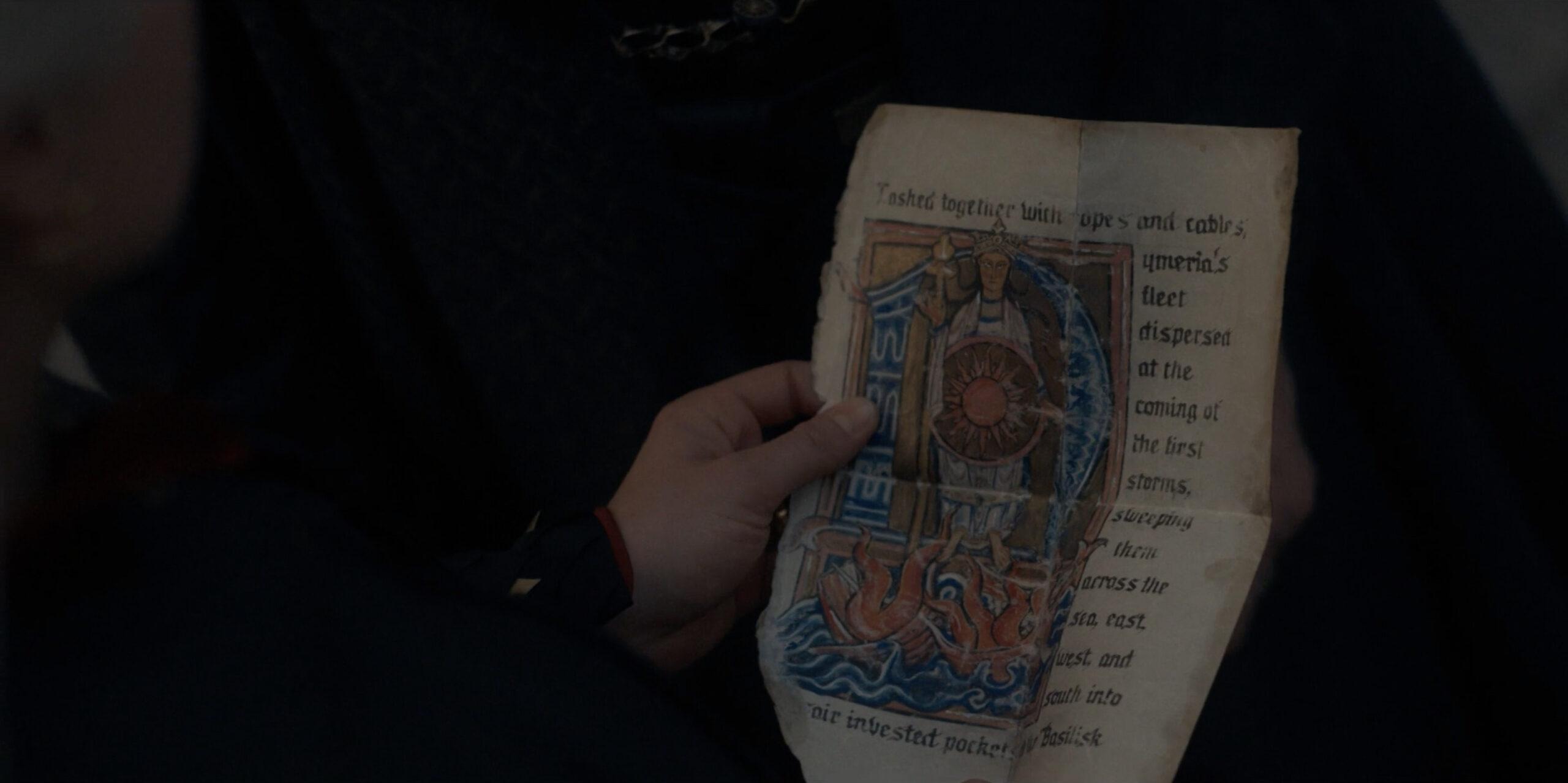

The page from the book

As part of the offer of peace to Rhaenyra, Alicent sends a page from a book with Otto:

It’s meant to be a reminder of the friendship Alicent and Rhaenyra shared as teenagers, and the scene from Episode 1 when they are studying under the Red Keep’s weirwood tree. This is the page that Rhaenyra tears out of the book. In that scene, Rhaenyra tells Alicent that she wants her mother, Aemma, to have a boy, so that she herself won’t have to rule. Instead, she can just fly on Syrax, explore the world, and eat cake. Maybe Alicent remembers that conversation well and wants to remind Rhaenyra of where her priorities once were.

But as far as symbolism goes, delivering this page to Rhaenyra also could send the exact opposite message. It’s about the maybe-mythical Rhoynar Princess Nymeria, who thousands of years ago navigated her people from one calamity to the next before settling them in Dorne, where she went on to rule for decades. Nymeria is a legendary ruler in Westeros and an inspiration to many women (including Arya, who names her direwolf after the warrior princess). Nymeria is why the Dornish laws of inheritance make no distinction between sons and daughters. To remind Rhaenyra of Nymeria is to remind her of how the Hightowers are usurping her birthright largely on the basis of her gender and little else.

Translating Daemon’s dragon song

I certainly don’t speak Valyrian, but David J. Peterson, the linguist who has worked on both Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon, does, and he posted a translation of Daemon’s dragon song:

Fire breather

Winged leader

But two heads

To a third sing

From my voice:

The fires have spoken

And the price has been paid

With blood magic

With words of flame

With clear eyes

To bind the three

To you I sing

As one we gather

And with three heads

We shall fly as we were destined

Beautifully, freely

The lines that stand out to me come from that second stanza: “And the price has been paid / with blood magic.” I can only speculate as to what this means; Fire & Blood offers no guidance, and this scene of Daemon serenading Vermithor does not appear in the book. But there are rumors that the Valyrians of old used blood magic to create dragons, perhaps by altering wyverns in some way. There could be a “price” that came along with that magic, and Daemon could be referencing that here. But if he’s alluding to some specific blood magic that he himself has done, then the show is creating a new dimension for the character that we won’t be able to explore until Season 2.

Welcome, House Celtigar

The lord who speaks up about the blacks’ dragons can be identified as Bartimos Celtigar by the crabs on his cloak:

As far as its strength goes, House Celtigar is not too notable. It’s a relatively small house that controls only Claw Isle, an island to the north of Dragonstone. What is notable about the Celtigars is that, along with the Targaryens and Velaryons, they are the only other Westerosi house that descends from Valyria of old. Like the Velaryons, the Celtigars do not ride dragons, but they are said to be fairly wealthy, with a castle “reputedly stuffed with Myrish carpets, Volantene glass, gold and silver plates, jeweled cups, magnificent hawks, an axe of Valyrian steel, a horn that could summon monsters from the deep, chests of rubies, and more wines than a man could drink in a hundred years,” per A Storm of Swords. Fingers crossed that the Valyrian steel axe makes an appearance in House of the Dragon.

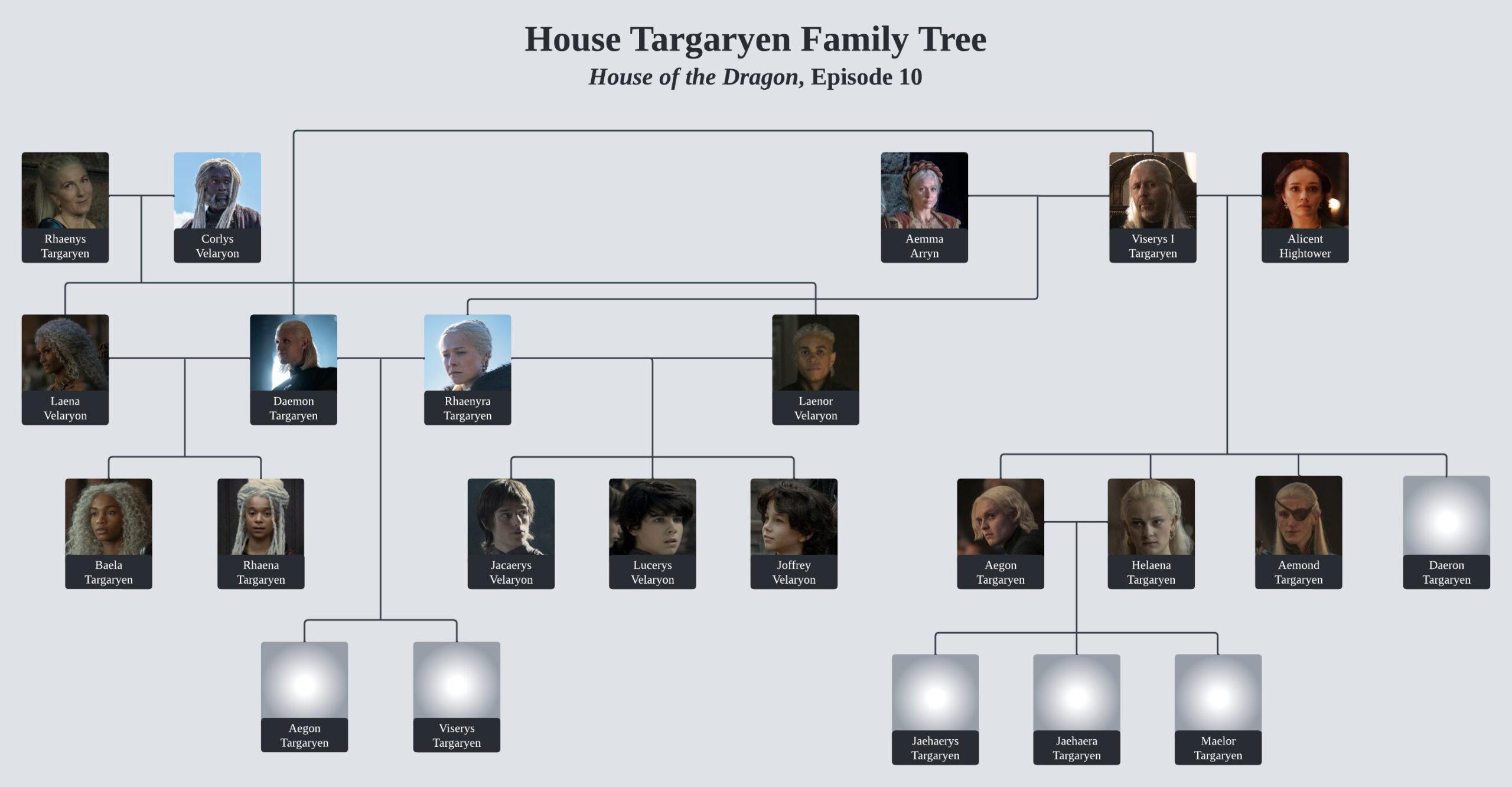

Family Tree Watch

I missed this last week, but the opening credits now have three streams of blood flowing from the union between Aegon II and Helaena, seemingly confirming that their third child, Maelor, will appear on the show. So I’ve added him to the family tree:

Next Time On …

That’s it for now! Season 2 is set to start shooting sometime next year, and the release date is “to be determined,” per Condal. But when House of the Dragon does return for Season 2, look for the series’ scope to expand beyond King’s Landing. We even seem to be ready for a return to Winterfell and the Starks.