You know those tweets and graphics that go around every so often—the ones comparing two anonymous quarterbacks? I have one of those for you. Here are two quarterbacking seasons, and I want you to pick which one you like better:

QB Comparison

The comparison is pretty clear—and pretty easy. “QB A” is a more aggressive passer. He throws downfield more often, yet still has a higher completion percentage and roughly the same rate of turnover-worthy plays. Yes, it comes at the cost of holding onto the football longer and taking a few more sacks, but he still looks like the better quarterback.

Are you ready for the big reveal? “QB A” is Joe Burrow—and so is “QB B.” The first data set is his 2021 regular season; the second is his 2022 regular season.

This may feel like a dumb exercise: Those two quarterbacking seasons look similar enough, especially when you include stats that don’t so much describe how a quarterback plays, but rather try to detail how well he plays. Burrow’s passer rating went from 108.3 last year to 100.8 this year. He threw 34 touchdowns to 14 picks, then 35 touchdowns to 12 picks. By EPA per dropback, he went from 0.15 to 0.10—from the sixth-best mark in the league to the eighth-best.

Widen the scope even further. Step away from stats that detail how well Burrow played, and use instead what’s as plain as the nose on your face: that Burrow is playing in his second consecutive AFC championship game this Sunday, in just his third season as a pro. We don’t need to do a season-by-season analysis of Burrow’s play to arrive at the very obvious conclusion that he is good, and the Bengals are making another deep playoff run in large part because he is good.

But to say that Burrow was good then and Burrow is good now simply does not capture what has happened to Burrow’s play over the last two seasons. Usually, when quarterbacks have two good seasons in a row while on the same team, working with the same coaches and throwing to the same playmakers, they are largely playing the same brand of football. Burrow isn’t. Burrow’s playing a remarkably different style of football this season. Burrow’s changed. Burrow has improved.

Let’s turn back the clock to the 2021 season. The Bengals have finished an incredible playoff run that ended just a few plays short of a Super Bowl victory. Rookie wide receiver Ja’Marr Chase has been a revelation, and second-year quarterback Joe Burrow has declared himself as an unimpeachable gamer with a penchant for the big play. The Bengals finished fifth in the league in explosive pass rate and led the league in expected points gained on explosive plays—that means their explosive passes were more valuable than the explosive passes of any other team.

This is an electric way to win football games, but it’s also unreliable. Because so much value was baked into so few plays for the Bengals, the totality of their offensive production was fragile. If they lost just a few of those deep passes, the offense would struggle to make up the lost ground. This isn’t just an outsider’s perspective—this is something Burrow discussed explicitly in the offseason.

“We just got to be more consistent, not rely on those big plays as much,” Burrow said in June. “Teams are gonna be playing two-high and making us check the ball down and all that, so we gotta be able to sustain drives and run the ball and take what the defense gives us.”

The focus on two-high coverages is an important one. As Dan Pizzuta wrote for Sharp Football Analysis before the 2022 season, Burrow’s depth of target was fifth in the league against single-high coverages in 2021, but it fell to 22nd against two-high shells. This is not necessarily bad or irregular—two-high defenses are built such that they discourage deep throws and force checkdowns underneath. But the Bengals were not suited to live in this world. Burrow led the league in EPA per dropback against single-high coverages, but was 13th against two-high defenses. The Bengals needed single-high coverages to continue excelling on offense, and as the 2021 season went on, they were seeing fewer and fewer single-high coverages. When 2022 came around, they needed a better answer.

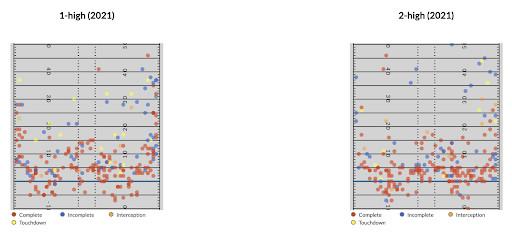

So what were the issues for the Bengals offense against two-high last season? We can take a look at Burrow’s target distribution in 2021 to understand part of the problem. Here are all the passes Burrow threw in 2021, as provided by TruMedia, separated by the coverages he faced. There are some slight differences in density—against two-high coverages, Burrow certainly threw underneath more often and downfield less frequently. But in general, where he threw the football didn’t change much.

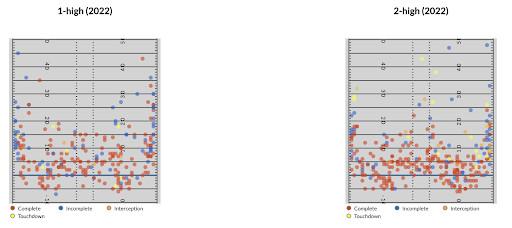

Compare these target maps with Burrow’s maps from this season, and the difference is apparent.

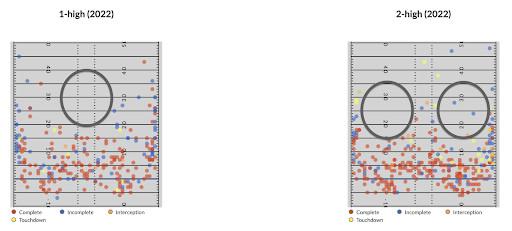

It becomes even easier to see when you add the safeties. The big gray gaps on the target maps are the exact areas we would expect the safeties to play in these distinct coverages.

Last year, Burrow was pretty much throwing whatever it was he liked throwing, independent of the coverage—and there are several reasons why he got away with this. He led the league in completion percentage over expectation, which was a testament to both his accuracy and the skills of his receivers at the catch point. His receivers were fifth in broken-tackle plus missed-tackle rate, which led to a ton of extra yardage after the catch—and again serves as a testament to Burrow’s ball placement.

But Burrow also just has a knack for this sort of stuff—for completing passes that he shouldn’t, on downs and distances and against coverages that he shouldn’t. As Kevin Clark wrote for The Ringer this past offseason, Burrow has the ability to throw into double coverage, change routes on the fly, and select the correct type of throw for each context—high-arcing, back-shoulder, fastball—because … well, because he just does. There are the skills of playing quarterback that can be divided and sorted into buckets, like arm strength and off-platform throws and coverage recognition and accuracy; and then there are the skills of playing quarterback that don’t fit neatly into any of the buckets. They get tossed into the formless unknown of what we call “feel” or “vision” or “sense.”

Bengals offensive coordinator Brian Callahan calls it a perception. “Joe’s greatest gift is he’s got an incredible perception of what everybody on the field is doing and where they are located,” Callahan told Clark in August. “So his ‘making every throw’ is gonna look a little different sometimes than [Aaron] Rodgers or [Patrick] Mahomes … When the pattern comes up, he can feel things happening, and his decision making is so fast and he’s so accurate that there’s no throw on the field he can’t find.”

Whatever it is, it’s something, and we know it’s there. Burrow has the knack, and he has availed himself of that knack to great achievement as a young quarterback. But because it is “perception” and not necessarily “processing”—because it’s an inherent feel for space and momentum and timing, and not the intentional, methodical dissecting of every and any defense—Burrow’s play style wasn’t really affected by defensive alignment. For much of 2021, Burrow just found whatever leverage he liked best for one of his talented receivers on a downfield route, and then he threw that.

There was a cost to this approach, however. Because the offense lived on the big play, and Burrow always felt like he had a magical deep bomb in his pocket, he took a lot of sacks. A sack on 9.6 percent of his dropbacks, as a matter of fact—third-highest in the league. Now, the Bengals offensive line was bad in 2021, as we all remember. But to start the 2022 season, Burrow was still taking a significant number of sacks; 11.7 percent of his dropbacks ended with sacks in Week 1, and 14.3 percent ended with sacks in Week 2.

Once again, this isn’t so much about any certain stat being bad—taking a sack on one of every 10 dropbacks is bad, but that’s not the point here. Burrow’s sack rate serves as a descriptor of his play style: that which he was intuitively doing. Every quarterback pays a cost for their own play style, especially in how they respond to pressure. Those who aggressively throw downfield into pressure (like Josh Allen) produce high interception rates. Those who quickly throw the ball away (like Aaron Rodgers) suffer from low yards per attempt, or low depth of target. And those who try to beat the pressure by escaping it, like Joe Burrow, take a lot of sacks. This is the three-legged stool of quarterback play, as coined by Adam Harstad of Footballguys, and save for a few exceptions it’s pretty inescapable.

Burrow has escaped it.

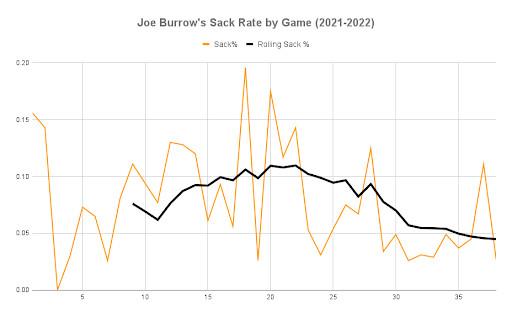

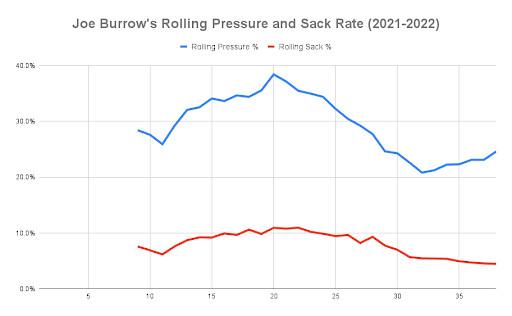

Here’s Burrow’s sack rate by game in each of the last two seasons, with a rolling average of the last 10 games charted along with it.

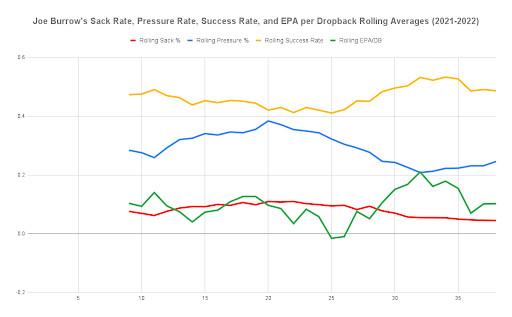

About 15 games ago, Burrow just stopped taking sacks. He went from regularly having sack weeks between 5 and 10 percent, with peaks above 10 and even 15 percent, to hardly having any peak weeks at all, and keeping his average week at or below 5 percent. This is particularly astonishing when you compare his rolling sack rate to his rolling pressure rate. Burrow’s pressure rate went down over time, as his line improved and he began intentionally avoiding sacks—but as his pressure rate has risen recently, given the improved quality of opponents and the injuries of his offensive line, Burrow’s sack rate is remaining stable.

If a quarterback’s play style is predictive of the sacks he takes, then Burrow is a different quarterback now than he was a season ago—and not just because the offensive line has improved, but because he has decided to improve himself. He has decided, of his own accord, to take fewer sacks. That is a change in play style, accomplished in just one season, early in Burrow’s career. That is extremely difficult to do.

But it isn’t the only one. Burrow’s target distribution has changed to better fit the coverages he’s facing, and accordingly, his splits against coverages are now more equal. Burrow’s a little worse than he was against single-high, but is now far better than he was against two-high—in fact, he’s better by EPA per dropback and by success rate against two-high coverages than he is against single-high. This, from the quarterback who dominated the league’s single-high coverages just last season!

Joe Burrow did what quarterbacks don’t really do; what players don’t really do: he changed his play style without an accompanying dropoff in efficiency. Usually, players just get better or worse within their own play style. They have a good stretch of play because they have some good moments of sack avoidance; they have a bad stretch of play because they get tackled by the shoestrings a couple of times. They face the coverages that tend to flummox them, and then they don’t. But if we’re to take the breadth of Burrow’s production this season as a sign of things to come—and I think that’s fair to do—then what we have here isn’t just a player who got better; we have a player who, despite being an excellent young quarterback just last season, changed his stripes. Changed his nature. And in doing so, got reliably, demonstrably better in the process.

It is typically bad form for a writer to tell a reader why something matters—it should be communicated over the course of the piece. But I am going to break form and tell you why this matters: because it is Joe Burrow’s superpower. It is a depiction of the one thing that separates him from the pack, that elevates him into the tier of elite quarterbacks, that makes him someone who can keep the Bengals’ winning window open for as long as he’s with the team, as he so boldly declared. It’s what gives the Bengals life in an era that could otherwise be thoroughly dominated by Patrick Mahomes. Burrow may not have the arm that Mahomes does, or the size that Josh Allen does, or whatever other defining trait we’ve crowned upon all the other top quarterbacks: but he has this. He has the knack, the perception.

If he were just another pressure-enduring, coverage-ignoring go-ball merchant like Matthew Stafford or Jameis Winston, as he appeared he could have been last season, then he would not be back in his second AFC championship game. What makes him different is that he is different. He has changed the way he plays because the game demanded it of him—and, if he can do that over and over again, evolving with the defenses scrambling to catch up to him, swinging with the pendulum of NFL changes, then the Bengals will be back to a third AFC championship game, and a fourth, and many more to come.