To observant followers of the Major League Wrestling brand, the end of 2022 undeniably marked an important anniversary in the company’s history. What has remained a matter of personal choice is precisely which MLW milestone each individual wrestling fan chose to honor during the recently departed year. Depending on whom you ask, MLW is just a shade over five, 10, or 20 years old, and rational arguments and data points could be cited to support any of those three opinions.

One milestone is unambiguous in its significance: When MLW Underground debuts on REELZ TV on Tuesday, February 7, it will establish a new high-water mark for the company in its quest to remain aboveground and achieve parity with World Wrestling Entertainment and All Elite Wrestling. For the first time in MLW’s history, U.S. households will have access to its weekly programming through basic cable.

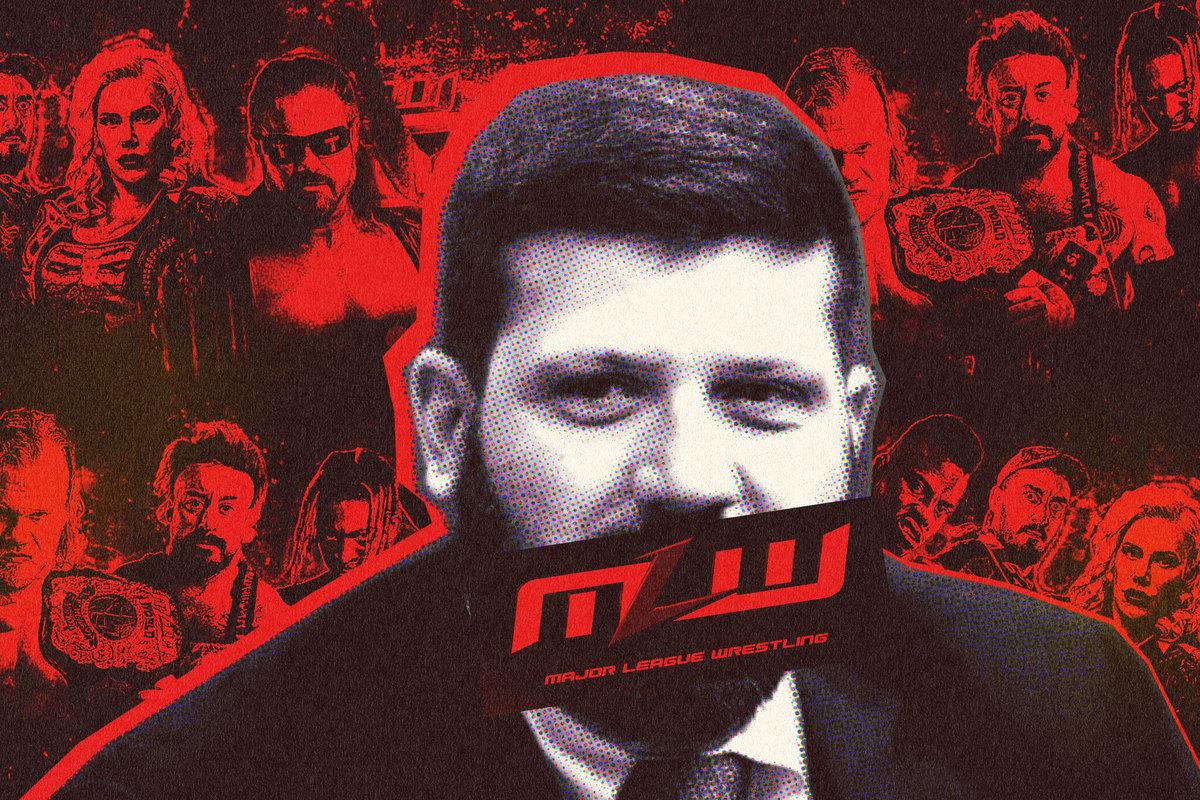

“Until this moment when we signed with REELZ, we’ve been the best-kept secret in wrestling, and all we needed was a bigger platform,” said MLW founder and CEO Court Bauer during an exclusive interview with The Ringer. “Now we have it, and now it’s on.”

One of the few North American professional wrestling companies to successfully shed the independent label and claw its way into the realm of mainstream respectability began as innocently and humbly as any pro wrestling dream can. Bauer passed the time in his weekday business and political science classes at McDaniel College in Westminster, Maryland, by daydreaming about creating his own personal pro wrestling sandbox. During the weekends, Bauer sat beneath the tall, shady learning tree of multiple members of the legendary Anoa’i wrestling family—Afa the Wild Samoan, Headshrinker Samu, and Afa’s titanic son-in-law, the 6-foot-4, 350-pound former University of Nebraska wrestler Gary Albright.

“Gary was working for All Japan Pro Wrestling for the legendary Giant Baba, and he basically said to Baba, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to have some sort of farm system in North America to develop the next generation of “Dr. Death” Steve Williams and Gary Albright and all those wonderful talents that made All Japan such an incredible company in the 1990s?’” recalled Bauer. “And so Baba, who unbeknownst to us was very ill, signed off on it and said, ‘Start developing this.’ Gary came back from a tour of Japan and said, ‘OK, let’s do this. We’ve got the green light.’”

With the blessing of a bona fide puroresu legend, Bauer set about developing the original incarnation of MLW as a North American developmental pro wrestling brand operating within the established ecosystem of All Japan. While AJPW’s near decade of noncooperation with outside entities had almost inarguably led to an elevation of the company’s average match quality, its foremost rival—Antonio Inoki’s New Japan Pro-Wrestling—had capitalized on partnerships with several outside entities, including World Championship Wrestling, Frontier Martial-Arts Wrestling, Wrestle Association R, UWF International, and others, in order to showcase wrestling shows that sustained the intrigue of Japanese wrestling fans.

Aside from Terry Gordy, Steve Williams, Stan Hansen, and Vader, no foreign wrestlers had entered the upper reaches of All Japan’s main-event heavyweight scene in the 1990s, with the roots of the latter two legends having been originally planted and watered in fertile New Japan soil. The idea of having a natural pool of exclusive foreign talent to draw from would certainly have been appealing to Baba, an owner and booker who seemed to view reliance on other wrestling companies as a critical vulnerability.

Much to Bauer’s eternal chagrin, the rapid unfolding of three successive events that would leave him scratching his head and wondering whether MLW would ever materialize for a public unveiling.

“Unfortunately, Mr. Baba passed away in 1998, and as we were trying to keep the thing moving forward under different transitions of ownership in All Japan, Gary Albright passed away in 2000,” Bauer recalled. “I was stuck here looking at this passion project that I really believed in. We had done a couple business models for it. I was getting ready to graduate college and thinking, ‘What am I going to do with this? Is it just dead?’”

When All Japan megastar Mitsuharu Misawa then loaded up his proverbial ark and absconded with more than 90 percent of All Japan’s roster to form Pro Wrestling NOAH in 2000, he left the depleted AJPW to contend with far weightier matters than the inauguration of a farm system. Yet, in Bauer’s mind, he had done just enough to give MLW a respectable shot at becoming a viable entity even without the support of an established brand.

“I’d done a lot of the work on my own,” recalled Bauer. “I’d gotten ‘MLW’ trademarked, and I got MLW.com. I’d done a lot of the groundwork to set this thing up. Then I said, ‘You know what? I’m just gonna do it on my own and make a go of this.’”

While several companies have laid claim to being the spiritual successor to Extreme Championship Wrestling, MLW can boast of at least temporarily reanimating the lifeless company’s skeletal remains. Within the span of a few phone calls, Bauer acquired the remnants of ECW’s production team, portions of ECW’s management staff, ECW’s inimitable play-by-play announcer Joey Styles, and also access to ECW Arena, where MLW staged its first show on June 15, 2002.

“It’s this weird thing where MLW was kind of forged out of an interesting concept for the future of All Japan, in the wake of ECW’s demise, and became this unique wrestling gumbo,” said Bauer. “On that first show, you had an All Japan presence. We had Taiyo Kea, who was one of the premier stars for All Japan at the time, and we had [Satoshi] Kojima, who was right there at the top, and he won our world title. So we integrated with All Japan from the jump but had a more informal relationship with them. We weren’t really developmental. At one point we called ourselves sister promotions from 2002 to 2004.”

“In that fabric, you also had a lot of what made ECW what it was, including a lot of the same stations,” Bauer continued. “We were on Channel 48 in Philadelphia, and we were on a lot of the regional sports networks throughout the country, from Fox Sports Atlantic to Fox Sports Pacific to Channel 52 in Dallas—the home of the old World Class promotion—to Sunshine Network in Florida. There was a lot of interesting overlap and familiarity if you were a fan of Japan, or if you were a fan of ECW. It made it an interesting destination for a lot of different fans.”

In Bauer’s mind, the thing that MLW did correctly as it stormed out of the gate was successfully delivering on the initial hype that the brand had created.

“Hype is such a key ingredient for promoting,” insisted Bauer. “In that period of time, fans were looking for what else was out there. A lot of people fancied using the term ‘the alternative.’ A lot of companies used that term, and they all kind of failed to deliver. In that post-WCW, post-ECW environment, it was really scorched earth. If you wanted that one flavor that WWE was presenting, it was a premium flavor, but it was just one flavor. If you wanted something else, you didn’t really have much to select from. People were trading tapes and looking at DVDs trying to find something to bite into. You had the emergence of MLW, and you had the emergence of what would become Impact Wrestling with TNA. I think in different ways, they filled different roles. Impact was trying to fill more of a WCW role, and we were the renegades.”

Despite his belief that MLW’s initial launch met or exceeded the fans’ expectations, Bauer attributed the subsequent decline and eventual closure of MLW in 2004 to two glaring personal shortcomings that would have compromised the growth of any wrestling company. The first weakness was Bauer’s lack of a practiced booking mentor.

“I remember when I had a show in Fort Lauderdale in the famous arena—War Memorial Auditorium—that had been around since I think [1950]. It was a great place that packed them in during the ’70s for Dusty Rhodes and Terry Funk. Let’s just say I didn’t do that,” laughed Bauer. “I remember Dusty looking through the curtain saying, ‘I’ve had a lot of sellouts in this buildin’; this ain’t one of those shows, kid.’”

Funk and Rhodes invited Bauer back to their room at a nearby DoubleTree hotel. As the trio watched an NBA basketball game on the television and Rhodes soaked his DoubleTree chocolate chip cookies in beer before scarfing them down, two legends steeped in the knowledge accumulated through thousands of wrestling bouts sat Bauer down and gave him his first lesson on the principles of properly booking a wrestling promotion.

“You can read about wrestling business and booking online in newsletters, and you can get a real baseline understanding that way, but the application and all the questions you have, you can’t get those necessarily answered when you go out and seek it from those sources,” said Bauer. “You’ll get a lot of interesting information and business perspectives, but you don’t really learn the true craft. You can’t do it from a newsletter.”

Bauer’s other insurmountable failing was his inescapable lack of relevant industry experience.

“It’s one of those things where you were too big to be small, and too small to be big. That creates growing pains,” conceded Bauer. “When you’re 22 or 23 years old, you’re full of gusto, and you see infinite possibilities, and you’re going for it. But then you need the experience to take it to the next level, sustain it, and apply it.”

In the wake of MLW’s 2004 closure, Bauer accepted a series of paid positions that afforded him the equivalent of a PhD’s worth of knowledge about professional wrestling and its adjacent industries. This included a multiyear term working as a member of WWE’s creative team, a stint as an executive producer for Lucha Libre AAA Worldwide, and significant time spent as a producer for UFC Fight Pass, with Bauer’s attention largely directed toward the development of content for the Combate Americas (now Combate Global) mixed martial arts company.

“The shared DNA between MMA and wrestling is incredible,” Bauer stated. “Being there in the trenches as the fighters are trying to make weight, and seeing what they have to go through, it’s exceptional. I have a lot of respect, fondness, and admiration for everyone in MMA, and I just grew from that experience. It also gave me a different perspective for producing and packaging wrestling. I came fresh off WWE, where it was so fabricated, scripted, plastic, and packaged, and to see the MMA version, which felt so authentic, I had to ask why wrestling couldn’t have some of these qualities. There were certain things from MMA that I thought I could extract and insert into pro wrestling that fans would actually be excited for. It’s part of the evolving journey of learning as you go. You just pick up little things along the way.”

By the time Bauer had gotten down to the business of enhancing the personas of MMA fighters, the MLW brand had already undergone an atypical revivification, having been reborn in 2012 as the MLW Radio Network. According to Bauer, this iteration of MLW began as a glorified marketing scheme that eventually launched a series of podcasting empires.

“Honestly, it was just an idea to unload our DVDs!” laughed Bauer. “It was supposed to be six podcasts, and hopefully we would sell our DVDs, get rid of the warehouse space in New York, and wrap it up. I wasn’t even supposed to be on it, Konnan wasn’t supposed to be on it, and I never thought that Jim Cornette and Ric Flair and all these other guys would be in the mix at one point. This was in 2012, during the early days of wrestling podcasts. It wasn’t in the days when you could type ‘wrestling podcast’ into Apple Podcasts and get blitzed with probably over a thousand of them. Back then it was pretty rare. You had guys on this podcast network like Jim Cornette and Ric Flair, and over time you had guys like Raven and former WWE writers pulling back the curtain.”

Unbeknownst to Bauer, the MLW Radio Network was just an intermediary step toward the completion of MLW’s sudden resurrection as a full-fledged and shockingly viable professional wrestling company.

“The podcast brought about a mixed hip-hop concert and wrestling podcast annual event called WaleMania, so I guess I’m a hip-hop concert promoter, too!” joked Bauer. “It was after the show, and I was sitting in the car with Wale and Jared St Laurent, who wound up being my COO in MLW. They were saying that I had to do just one more show. I really didn’t want to. Being a promoter is such an intense, 24-7, all-hands-on-deck job. Not a lot of people go out and look to do that job. It’s a tough job. I said, ‘I’ll do this one show—this one shot—and I’m done. I’ll get it out of my system, and if you guys really think I should do this, I’ll do it.’ The show was called MLW One Shot, and it happened about five or six months later on May 10 of 2017. I had great support from Wale to kick it off.”

With MLW officially relaunched, Bauer quickly went to work capitalizing on the experience and connections that he had accumulated during the decade that elapsed between MLW’s death and resurrection. By January of 2018, he completed a deal with beIN Sports and was expecting MLW to make the sudden and miraculous transition from inanimate to inescapable by landing on a network that would put it into approximately 50 million U.S. households. That was when Bauer says the rug was abruptly snatched out from beneath him.

“By the time we were just premiering, beIN’s deal started to collapse,” remembered Bauer. “DirecTV went away and Comcast went away, so that 50-million-household number wound up closer to 5 million. As you go through the process of doing all this, you learn that it’s always about bootstrapping. You have your business plan and you have your strategy, but you’re going to have to adapt out there on the battlefield. You have to find out if you made the right pivot or you have the right strategy. You’ll have good fortune and reversals of fortune, and you have to learn to navigate those waters.”

Luckily for him, Bauer’s time filling several roles in the support of multiple companies had empowered him to chart a course for clear waters even while swimming in a choppy current. This time, he had learned from previous mistakes, and a downturn in expectations for MLW wouldn’t simultaneously sound its death knell.

“The original MLW’s TV package was really piecemeal in how it was structured,” explained Bauer. “But beIN Sports—even though they had diminished market penetration—they enabled us to grow in a lot of ways because we were getting a rights fee. That helps. If you have exposure and a rights fee, that’s really the engine that runs every major wrestling organization in America, whether it’s WWE, AEW, or us. So to have that and be able to then expand upon it with a Spanish-language feed every week, that allowed us to find a way to tap into a new market that really wasn’t being served.”

So now that MLW has acquired a vehicle for reaching cable TV viewers in the form of REELZ, how will it catalyze a national fan base and stave off any future catastrophes?

“We are a raw, unvarnished, ultra-realistic product,” boasted Bauer. “[Underground] is the fastest, quickest hour in wrestling, and it’s damn good. All of our competitors think having more hours means they’re better. MLW Underground is all killer, no filler, and I think that’s what’s going to make people enjoy it when we come to REELZ with Underground. The other companies are going to keep running the same plays and have their identity be that they’re going to keep signing random wrestlers to make big splashes for one or two weeks, and then they’ll vanish into the witness relocation program. Everyone on the MLW roster has a focus, and we make sure it counts. There’s no politics here, just damn good wrestling.”

Bauer further believes that MLW’s ability to creatively differentiate itself from its competitors will help it carve out a permanent space in the industry where its rivals will be reluctant to follow. This includes the proper use of different weight divisions; Bauer doesn’t think any mainstream wrestling companies have ever gotten close to using them correctly.

“When I was in WWE, if you were the cruiserweight champion, that was basically a death knell,” said Bauer. “You were given a ceiling. Even if you lost the belt, you were now pigeonholed into being a cruiserweight. It’s something a lot of wrestling promoters have struggled with because they never worked in boxing or never worked in MMA, so they don’t have a real understanding for how it works and how it could work. That has helped to differentiate us from our competitors as well; they don’t have real weight classes. They might have a token thing like in WWE with the 205 Live division. It’s a fad for them, like with the hardcore title. In MLW, it’s the essence of what we are at our core. We have weight classes. I think that feels more here and now than dragging along a brand title and having it be the name-of-your-show championship. You can’t draw fans more out of a fight experience than to do something like that.”

Despite ostensibly offering something entirely new, MLW retains touches of several wrestling companies, from All Japan to ECW, in its DNA. Taking that into account, Bauer insists that sidestepping the ghosts of promotions past has permitted MLW to escape from its plot next to ECW and so many of ECW’s other spiritual successors in the graveyard of dead wrestling companies.

“Back in 2002, it was really me, and that was about it,” confirmed Bauer. “I was doing everything, from designing T-shirts to producing Joey Styles in a basement in Westchester for the weekly show to booking the travel for all of the talent to writing the TV show. Because [Paul] Heyman didn’t delegate, ECW became the example of a place where you could have all these great things happening, but you were also building a house of cards. You have to be surrounded and supported by a great team, and thankfully I am.”

So whether you identify the penciled-in growth mark on Major League Wrestling’s doorframe as the measurement of a company that is just over five, 10, or 20 years old, we can at least marvel at the fact that the wrestling promotion Court Bauer brainstormed during his college accounting class is even standing upright. And no matter what comes MLW’s way, the simple fact that MLW Underground will finally be accessible to tens of millions of households is a testament to the fact that sometimes it takes decades of heartache, turmoil, and tireless labor to generate an overnight success.

Ian Douglass is a journalist and historian who is originally from Southfield, Michigan. He is the coauthor of several pro wrestling autobiographies, and is the author of Bahamian Rhapsody, a book about the history of professional wrestling in the Bahamas, which is available on Amazon. You can follow him on Twitter (@StreamGlass) and read more of his work at iandouglass.net.