North Texas Central College self-identifies as “the oldest continuously operating two-year college in Texas.” The school has undergone multiple name changes. Similar to Texas State University, it has renamed itself to make it sound like a more appealing destination and to look better on a diploma or résumé. From 1961 to 1974, the school was named Cooke County Junior College, and embraced its goal of producing associate’s degrees meant to allow students to transfer to universities, and one-year instructional certificates tied to specific careers. One of the courses it currently offers is Architectural Drafting—Residential, part of its Engineering Technology Area of Study. In a perfect world, Aurelian Smith Jr. would’ve taken that class, or its past equivalent, in the fall of 1973, shortly after his high school graduation. Almost 50 years later, Smith aims to build on what his past, his persona, and the people around him have repeatedly broken down. Jake “The Snake” Roberts is truly putting himself together, for the very first time, brick by brick, piece by piece.

One of the core objectives required to complete the drafting course is communication. It’s a skill that Jake Roberts has only very recently honed when it’s needed away from crowds and backstage interview segments. His development was immediately and continually stunted, Roberts coming from, and emulating, a string of broken relationships. Presently, he’s days away from the premiere of his episode of Biography: WWE Legends. After years of living like a sailor, the only vice he seems to maintain from his time on the high seas of bars, back roads, and bingo halls is the cursing. He’s more than willing to color his conversation with all the words you’ll no longer hear on Monday or Friday nights. “Doing this thing and having it come out so well, I think that I’ve finally had the one happen that really tells the whole story. … It’s not pretty. It’s got some rough, nasty edges to taste, but it was life and it was the truth,” Roberts told The Ringer. “I didn’t candy coat anything. I’m sick and tired of seeing these docs where these guys go out and put on and never have a fucking problem and never did things. Are you fucking kidding me? I was there. I watched your dumb ass!” He made a point to be as transparent as possible in the documentary. Jake Roberts does not blame anyone other than Jake Roberts for his struggles. Not peers, not dealers, not women, not even family. The last party, specifically his parents, may have been spared Jake’s blame, but it’s difficult to ignore the correlation between childhood trauma and adult struggles. In the opening 15 minutes of the documentary, we’re given the details of his upbringing, which will likely inspire anger in decent folk, and outrage in the emotional. Jake Roberts, with his trademark handlebar mustache now an endless winter of white, is the product of an underage mother and a pedophilic father. Aurelian “Grizzly” Smith Sr., a 6-foot-10, 350-pound professional wrestler, left Jake, his siblings, and mother to start a new family about five years later. Jake’s mother was too young to raise her children on her own, so that responsibility was left to the children’s maternal grandparents. After the grandparents passed away, the Smith children were sent to live with their father and new stepmother. This would begin a cycle of sexual abuse, with Grizzly Smith repeatedly assaulting his daughters, and his wife assaulting Roberts. Jake’s stepmother would physically abuse him after her sexual assaults, expressing the disappointment Senior would show if he found out.

Jake eventually changed his career path because he wanted his father’s approval. After a conversation between the two at his high school graduation, Jake gave up on his architectural dreams to pursue his father’s recommended path: professional wrestling. After his first match, his father intimated how disappointed he was in Jake’s performance, leading him to refocus and take the craft seriously. The mind that wants to build, the mind that can see structures before they are on paper, that’s the mind Jake Roberts would apply to professional wrestling. “I put a lot of time and a lot of thought into what I do out there, man. A lot of it comes naturally. But the things that come natural to me are because I’ve learned through my life what works and what doesn’t. How to go about achieving what I want to achieve in the ring. There are certain things that I picked up going through life that I use, and those are natural things. The way I walk, the way I talk, the way I look at people.” Learning what worked, and what didn’t work, would be mostly on-the-job training. Roberts’s history of substance misuse is well documented. But the details, the actual accounts of some of the lowest lows, border on the hyperbolic.

A key component of effective communication is finding the flaws in past conversations/interactions and then not repeating them. Similar to his high school graduation experience, an older Roberts, at this point well established in the World Wrestling Federation (and married to his second wife, Cheryl Hagood), traveled from Georgia to Texas for his oldest daughter’s commencement ceremony. They agreed that after the ceremony, she’d make the return trip with him to live with his new family. Jake Roberts smoked crack cocaine the entire 17-hour-plus trip, according to the documentary. Mirroring how Jake has had to maneuver in dangerous situations, his daughter explains in the documentary that she’d preferred to drive and allow him to smoke rather than let him do both at the same time. At the height of his success, doubt cast at an early age crept into all aspects of his life, even when his persona, his promos, and his matches were lauded. “I never watched television when I was wrestling. I never heard what the commentators were saying or what Vince was saying. And you go back now and hear some of that. I go, ‘Holy shit, man. They did hold me in a high regard,’ and because of my upbringing, and what I went through, I never thought I was good enough. I was very insecure, very insecure. So that’s why everything was so deliberate in the ring. I wanted it to be absolutely fucking perfect. And I think I pulled it off.”

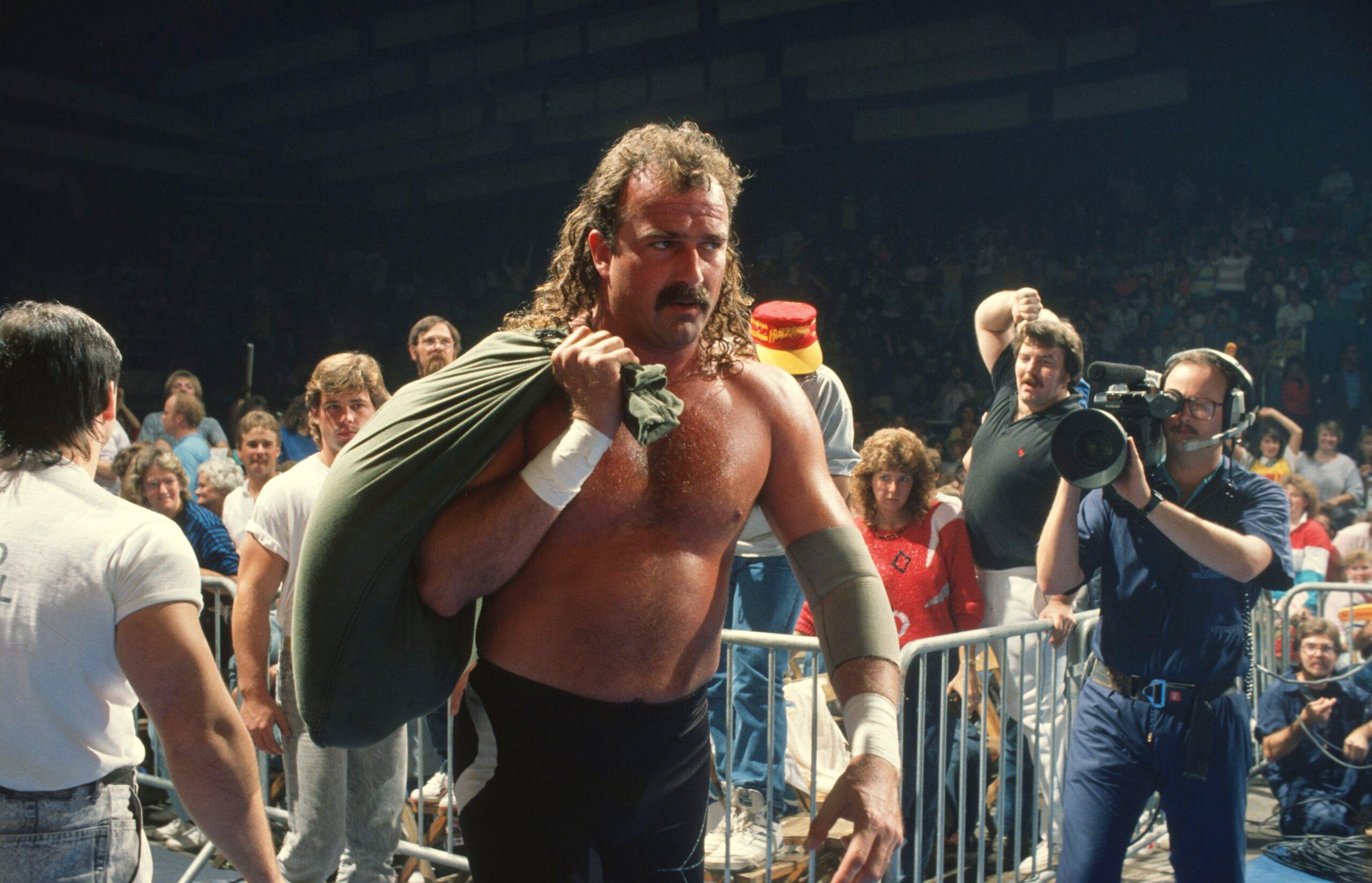

Jake Roberts would become one of wrestling’s biggest stars and would do so in his own way. Lots of students, specifically at the community college level, think that the best way to appeal to their university of choice is to take as many classes as possible to put onto a transcript. They are often reminded that it’s not how many classes you take, it’s the grades you get in the ones you take that matters. In a world of vivid color, over-the-top antics, and arguments with the volume on 11, Jake Roberts was in full control, deliberate, almost plodding with his promos and in-ring style. With his python Damien in tow, Jake would strike a practical fear in opponent and attendant alike, afraid of possible poisoning, or suffocation, at one false move. Roberts understood that being the bad guy meant his opponents—and, at times, the audience—would live in fear of what he’d say next, of what he’d do next. “That was intimidation. Intimidation. You walk slow, you walk sure. You carry a big stick. I didn’t need to jump around and flutter around. Let the young boys do that.”

Perhaps the most stressed core component of the Introduction to Architectural Drafting course is critical thinking. This tends to be much easier when you’re surrounded by examples of the right way to approach a situation. For Jake Roberts, that was pupil turned peer turned life coach Diamond Dallas Page. Page, one of WCW’s most prolific participants in the Monday-Night Wars, had almost a full decade in the ring before reaching stardom. Known for his ability to make even the most mundane details of a wrestling tale feel like a childhood fable, he doesn’t mince words about where he got his style. “I would say I stole a lot from Jake,” Page says, looking back on the swagger and delivery that helped him earn multiple world titles and the adoration of millions at the hottest time in the industry. “I’d be the first to say it, but Jake loved how I made it my own. And I never even realized that until I’d watched one of the matches. … It was just instinctively I was around him so much. There was a guy on the road one time who had 40 VHS tapes of Jake that were full-hour tapes, 80 hours of just Jake, and he brought them in a box and gave them to Jake. And I go, ‘Man, I want to tear through that.’ He goes, ‘You can have it,’ and wish I still did. But I watched every minute of all of those tapes. There’s a little piece of [“Macho Man” Randy] Savage in me, there’s a little piece of ‘Mr. Perfect’ Curt Hennig, there’s a little piece of Terry Funk in me, there’s a lot of Jake, and I just love those styles of work in the ring because all of them were believable as hell. And to me, that’s the most important thing, that people don’t see through your work. … I think Jake Roberts was one of the most realistic people ever in a place where everybody knows it’s predetermined. Jake made it real.”

After their wrestling days were over, he moved both Roberts and longtime friend/nWo frontman Scott Hall into his home to help them battle substance addiction with tough love, positive thinking, and a particularly effective fitness regimen. This upward climb to sobriety was covered in 2015’s The Resurrection of Jake the Snake. Roberts, a staple of the early WrestleMania years, had spent the late 1990s and early 2000s playing high school gyms and community centers, and was in poor shape externally and internally. Knowing that this wasn’t how he wanted his story to end, he reached out to Dallas Page for help. While it was Roberts who came to Page, that didn’t mean that path to peace wouldn’t cover tough terrain. Page still recalls some of Jake’s toughest moments, particularly of self-doubt. “He’d come down one night, and he was, like, so mad. He punched a marble table and a marble counter, and I was like, ‘Dude, what are you doing?’ He goes, ‘I’m such a loser.’ I’m like, ‘Stop saying that.’ He goes, ‘I’m such a loser, Dallas. I’m so pissed at myself.’ And I pull him aside, and I go, ‘Come here. Let me show you something.’ We walk in the bathroom off the living room, and I said, ‘What do you see?’ He goes, ‘A loser.’ I go, ‘Stop saying that … look at the shirt you’re wearing.’ And the shirt was a skeleton, was waving a flag, and wasted youth on the flag. I said, ‘Every time you wear that shirt, you catch it in the mirror. You tell yourself what you wasted. You wear shirts with Manson on it. Would you want your kids to be around Manson? Hell, no.’ I go, ‘What are you doing? The story you tell yourself is everything, bro. You should have positive energy on there or ‘Unstoppable’ or ‘Never give up.’ I go, ‘That’s what you should be wearing.’ And he goes, ‘You know, you’re right.’ And he went upstairs for 20 minutes, and he came down, and Jake’s an artist, and he drew this banner and wrote through it, ‘My history is not my destiny.’ I was like, wow, that’s powerful. And that became the story he told himself.”

Selfishly, Page appreciates not only Roberts’s recovery and sobriety, but also that he’s regained his friend after all the years of struggle. Even in the early days after completing Page’s program to the best of his ability, Jake Roberts had to fight off relapsing. “After being in this house for two years and moving out in that first week, seeing where I was at and [questioning his progress]. ‘But what if? So the first time I [go] to a meal by myself, am I going to pick up a drink or what?’ And I didn’t. So those early victories just kept me rolling.” Where they once sat isolated, sharing space, time, and conversation within the confines of Page’s home, they can now experience the world, both with each other and the people they hold close. Jake Roberts has begun to build relationships with three of his eight children. He fishes with his sons, who have families of their own, as they talk through finding the right way to establish understanding. He’s even resumed his relationship with Hagood, his second wife, 26 years after their divorce. “Today he’s back with his wife, Cheryl. Are you kidding me? That’s the coolest thing ever. They were at my party this year, and Jake doesn’t normally do parties because he doesn’t want to be around the alcohol and liquor. But now he’s cool. He’s good with it, and they’re great together. My wife, Paige, and Cheryl and Jake, we all went up to Boston to go to see Aerosmith, and we saw them at Fenway. Jake right now is living his best life.”

With most college courses, the final tends to weigh heavier than any assignment, quiz, or previous test from that semester. It’s that culmination of the skills you’ve acquired, the knowledge you’ve retained, and how you can apply that to your future courses and tasks. North Texas Central College’s Architectural Drafting—Residential course has a term project that accounts for 20 percent of the student’s final grade. It’s the difference in most cases between passing and failing. When you ask Jake Roberts what he’s learned on his long journey toward peace, toward normalcy? It’s a lot like a degree. You take it for granted when it comes early in life, but you know its full value if you earn it later in life. Jake has found stability, in the same way that others like Sting and Arn Anderson have, being legends and mentors to talent on the All Elite Wrestling roster. Still every bit of 6-foot-5, Jake holds his own when backing acts like the towering Lance Archer to the ring. Jake Roberts takes pride in being someone whom younger acts can turn to about their own personal struggles. “I’m able to help some of the young guys. I’ve steered a couple of guys that were struggling with alcohol. I’ve been able to help those guys out, which makes me feel unbelievable. Well, I sponsor several guys that are struggling fans. They’re fans and I’m helping them. So anytime I can help somebody with addiction is a great day, and I enjoy doing it, and I take pride in doing it, and I just like who I am today, man. Standing tall forthwith. And it may be a little rough on the edges, but I’ll give it and I’ll take it.” He’s able to reflect not only on his life, but also on the business that he helped make special. Still one of the brightest minds around, this version of Jake Roberts is critical with a smile, reflecting on his signature move, the DDT, and its place in modern wrestling. “Every time they DDT somebody,” he starts, with eyes bright and shoulders broad and pushed forward, “and they don’t beat them with it, people say to themselves, Jake Roberts did it. You didn’t fucking get up!”

One course does not an architect make. There are more classes, studying, finding the right school to finish your program. There’s testing, getting hired. There’s finding people to trust that what you’re building will stand up against code, against storms, against time. Jake Roberts can’t get time back, but he’s taken steps to make the time that he does have left matter. “It’s real simple. I became a man,” Roberts explains. “Each day that I stay sober is another victory for me. Believe me when I say there ain’t no way in hell I’m picking up again. I enjoy who I am today. I like waking up and looking in the mirror and saying, ‘Hey, dude, you’re a bad son of a bitch, man, come on, let’s kick some more ass.’ And I like being able to pick up the phone and not worry about what’s going to be said on the other end. ‘Like, Jake, you fucked up last night. What the fuck are you doing?’ Man, I’m glad that shit is over. Are you kidding me? I’m glad that I could remember what I did yesterday. I may not remember what I had for breakfast, but I know that I ate. It was all good. So where I’m at today, man, I’m walking tall and kicking ass and taking names.”

Cameron Hawkins writes about pro wrestling, Blade II, and obscure ’90s sitcoms for Pro Wrestling Torch, Pro Wrestling Illustrated, and FanSided DDT. You can follow him on Twitter at @CeeHawk.