During the last few days leading up to this year’s Elimination Chamber show in Montreal, in something that has become tradition before “gimmick” shows on the WWE calendar, the VenPurr Bros. and I spent roughly 15 hours in the Palace of Wisdom running through every single Chamber match in order.

(My daughter didn’t get to partake in as much of the Chamber “tape eating” as she would have liked, or at least I assume based on her reaction to me starting Goodnight, World! with her way, way too soon after Asuka arrived on-screen. Though it’s also possible Thiz just misunderstood the concept of “tape eating” and was upset about missing out on “snackies.”)

While the stories of the matches (both on micro and macro levels) ranged between “historically great” and “mildly interesting,” what seemed most important to us while we watched was how much the first four of these matches—over the course of almost FIVE YEARS— looked like the garbage fire the fifth match actually was.

And by that, I mean this shit was hard to watch (and without even helping Tracy Jordan win his EGOT).

I had never begrudged WWE for taking much longer—January 21, 2008, almost a full 10 years after HD was first broadcast in the U.S.—than nearly every other major (or not so major) sport, as well as a plurality of network television, to find itself filming and broadcasting in high definition. Well, that bootlicking bullshit ended last week. After watching the first five editions of the Chamber match, I felt as though I’d seen Jack Horner’s worst fears come to life.

Trudging through an orgy of shots noisily obscured by steel beams, routinely punctuated by bloodied faces mashed into chain links that comprised the “walls” of the structure, all with seemingly arbitrary cutbacks to a useless “hard cam”—the stationary camera that traditionally functions as a recurring establishing shot for wrestling matches—looked terrible, which almost certainly wasn’t intentional but was at least partly a function of the lo-fi presentation that permeates the entire era.

Like Floyd Gondolli trying to keep himself flush with lollipop and butter-stick money by switching to videotape to cut costs, WWE’s reluctance to join the high-definition future (presumably over cost concerns in the other direction) led it to nearly destroy any credibility the Chamber idea had developed before the concept ever even had a chance to turn into The Final Stop on the Road to WrestleMania™ by presenting it in such an embryonic form.

If this sounds—may God have mercy on my soul for this pun—extreme, that’s only because you weren’t around for the fifth Chamber match, at Extreme Championship Wrestling’s December to Dismember in 2006. Considered one of the worst shows ever produced by WWE, it led to Paul Heyman being relieved of his duties in charge of ECW at the time, the (albeit brief) retirement of the Big Show, and release requests from multiple ECW originals, including Tommy Dreamer and Stevie Richards. Which is to say: The Chamber match (and everything that came before it) went so bad they took Paul Heyman off TV.

Unequivocally the worst Chamber match and easily one of the worst main events in WWE history, the attempt to turn ECW’s version of the Elimination Chamber into the WCW Chamber of Horrors (give or take an Abdullah the Butcher botch ... or six) was a failure on every level. The chamber looked terrible and is perhaps the nadir of WWE’s presentation in the modern era—that is, in a “low production values” sense, as WWE has obviously put way worse stuff on TV from an ethical, moral, and cringe perspective—and the actual match was the “Kennel from Hell” but with a brand shitting all over the ring instead of a pack of scared dogs.

Presumably, over concerns that the multiton steel structure that they had advertised as a violent torture chamber they were all trapped in wouldn’t be able to get the job done, weapons were placed in each pod for individuals to wield against their opponents. Or, that’s at least what we were told, but it’s unclear how some of these, including a whole-ass table placed in eventual winner Bobby Lashley’s pod, were supposed to be used against someone in a situation like the Chamber.

As a general rule, the Chamber is a busy match for the eyes, and on this night, with the weapons crowding each pod and the house lights seemingly turned all the way up, there was essentially no visual contrast between the spectacle going on in the ring and the crowd behind it. This meant that every time the camera went to a wide shot (to see the crowd not reacting to anything in the ring) it gave the entire thing all the aesthetic charm of an indie show at a high school gym coupled with the visual clarity of the last season of Game of Thrones if they had somehow filmed that with the sun placed directly on set with them but then covered the lens with the mop water from a janitor’s bucket.

While things like lighting and mise-en-scène or depth of field are normally not of concern for professional wrestling shows, the very specific ways in which the match played out from a visual standpoint made me wonder about whether how much of what I was watching was WWE’s total apathy toward what it was putting on-screen. (Smaller shows sometimes do have problems, but their issues usually come from bad camera equipment and audio that sounds like it was recorded from a very uncomfortable place, like the back of a Volkswagen.)

So I asked Timothy Burke—for those unaware, in addition to creating one of the most frightening pieces of media criticism of recent vintage, Burke (formerly of Deadspin, which was a good website) runs Burke Communications and is one of the foremost experts on broadcast standards and technology working today—if the relatively poor quality of the footage from this match and era is, at least partially, a function of a lack of care or concern about the visual presentation or something else. In this instance, it seems like he saw a real “Por qué no los dos?” situation.

“Over the years different processes were used to ingest WWE archives into ‘the Network’—some of them better than others. Looking at this ECW December to Dismember, my guess is that this was initially archived in a digital format but then recaptured through an analog capture process. I’ve seen this in a lot of the NBA’s content as well, where there’s both digital pixelation and chromatic fringing that are telltale signs of both aspects of re-production,” explains Burke.

This is in contrast to the Attitude Era broadcasts, which maintain at least some fidelity to the original presentation. “If you look at the WWE Attitude Era stuff that was recorded in, I’m guessing, 3/4-inch U-matic tape, then digitized using a very high-quality comb filter and time base corrector and all that, it looks much better despite being up to 10 years older than this ECW stuff because someone else or somewhere else did the digitizing.”

Though, as Burke was quick to point out, WWE’s decision to change the way it handled footage was “not about cheapness, it was about the trends. You will see the exact same thing in replays of ESPN college football games from that era. There were extremely high-quality ways to save this stuff back then it was just ... expensive and not many people did it. If you find original air tapes, for example, those are always going to have the highest quality, assuming you have decent digitization equipment. But as we know, air tapes were not always kept even into this century.”

So while it may feel good (and I certainly wanted) to blame Vince McMahon or a lack of foresight by his production team for my trouble with getting through the first few Chambers, Burke makes it clear that this was standard operating procedure for an industry that almost certainly did not see a broadband-enabled streaming future that would become the primary distribution model for most entertainment in the world.

“There was a period of time from, like, the late ’90s to the mid-2000s where it was common to archive stuff in a lossy digital format that was easier to work with than analog tape but was visually inferior to a well-recorded, well-kept 3/4-inch analog U-matic or similar broadcast tape.”

And, for all of its faults, WWE has actually done a decent job of maintaining its library, which itself contains nearly the entirety of meaningful matches from the territory era and, by extension, the entire visual history of a significant cultural medium, at least in terms of North America productions.

“Overall, the Network is an amazing thing and WWE has preserved its history better than just about any sports league. The NFL—and I say this having worked with them recently on something related to the Immaculate Reception—kept almost nothing. They relied on NFL films to tell their history, and so decent recordings of their television broadcasts basically don’t exist.”

All of which is to say that while a lot of things can be said about WWE as it relates to the ways in which it goes about its business on the talent or international relations side, at the very least, the production side wasn’t in some budgetary death spiral that WWE only managed to pull out of in early 2008.

However, even with the understanding that from an archival perspective, there were industry-wide issues with how these were digitized and transferred from their original forms, having watched these shows live it wasn’t like they looked good. Which seems like an objectively bad original decision.

To create an entire match type and visual spectacle for your wrestling company, but not spend the time, money, and effort (as the switch isn’t a simple one) to present it in the best possible way, is bad for business. The development of the Chamber was, however, clearly done for a reason, and in order to figure out what that might have been, we’re going to need to talk about camera blocking.

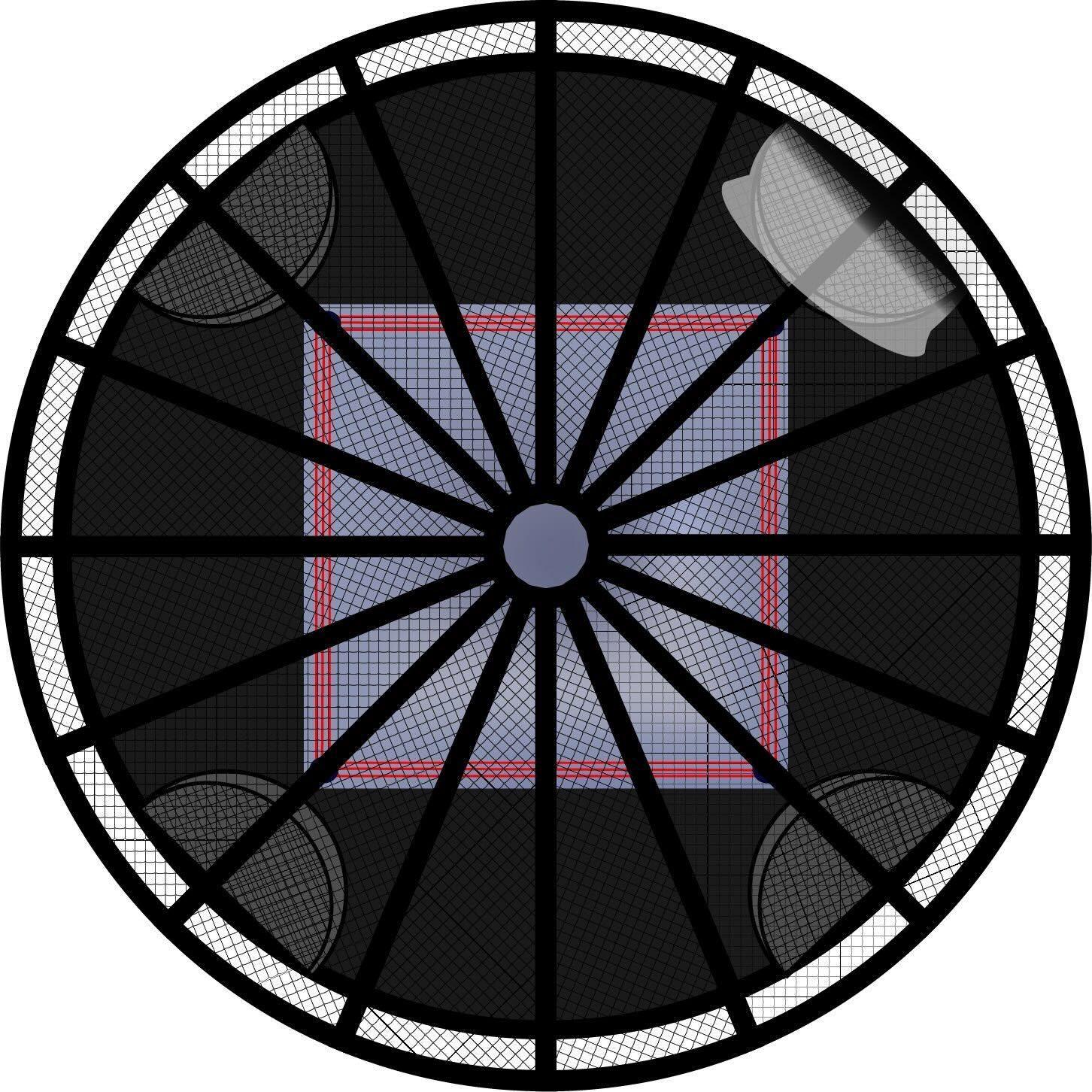

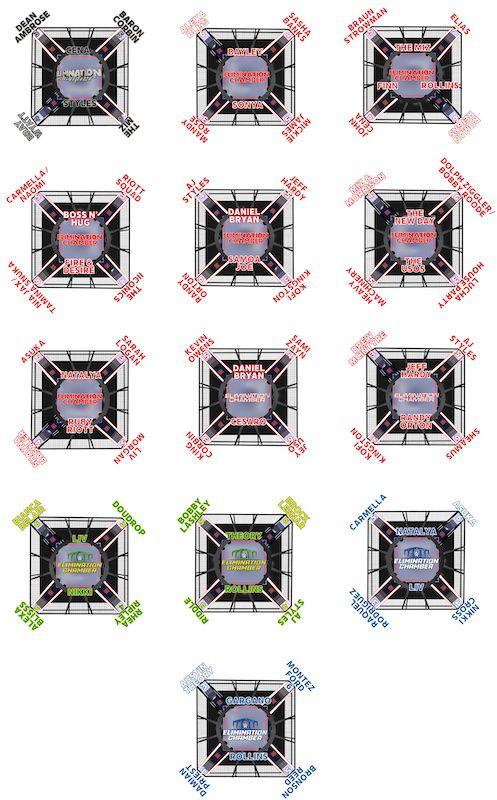

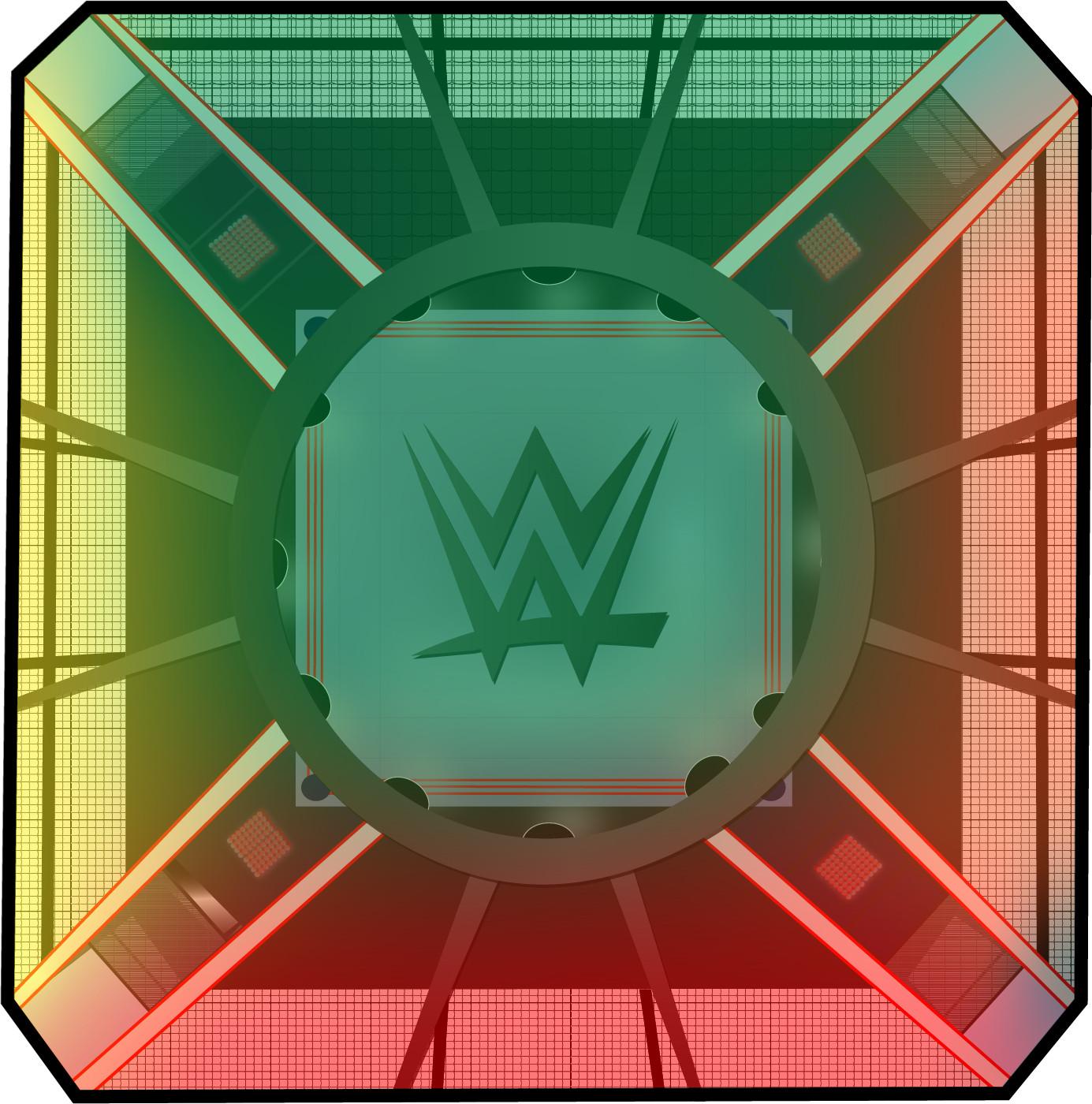

This is the original Elimination Chamber—there has since been an updated Chamber structure, first introduced in 2017 after a one-year hiatus for the concept—or at least a mediocre render of one. As you can see, the inner sanctum has four semicircular pods positioned at each corner of a ring placed centrally inside the circular superstructure. The spotlight at the top right represents the winner, which is a visual concept cribbed from WWE’s “selection” process for the next entrant in this version of the Elimination Chamber (which was replaced by LED light bars mounted to the roof of the chambers in the new iteration).

While the inaugural match—which took place at Survivor Series 2002 and featured Shawn Michaels winning the World Heavyweight Championship in just his second match back after a four-year hiatus—was unequivocally the best of the initial handful, it completely skewed expectations for how dynamic this match could be in its then-format from a visual perspective. The show’s host, Madison Square Garden, rather infamously had the entrance positioned on the hard cam as opposed to the left of it during this era, which looked great for surprise Royal Rumble John Cena entries or Rock chair shots during Triple H–Cactus Jack matches but was distracting for pretty much everything else.

This floor configuration appears to have provided WWE more distance between the camera and the chamber, allowing it and the crowd to be framed in full, giving viewers a total picture of what they were seeing, as opposed to the cropped shots that cause the Chamber structure (as opposed to a view inside the Chamber itself) to completely block out the rest of screen.

So, while the visual that went along with Michaels’s shocking World Heavyweight title win after four years on the shelf is one of the most memorable in the company’s history—an absolutely biblical pop, on par with CM Punk’s Money in the Bank pop in Chicago, ever so slightly above Cena’s and H’s returns to the same building, and, if I can avoid some recency bias, definitely better than Sami Zayn’s arrival at the 2023 Elimination Chamber (though, it should be noted that those are all entrances, and it was very clear watching from home that the entire Bell Centre would have been Raptured if Zayn won)—it’s something WWE couldn’t properly replicate (at least not well enough to put in the kind of retrospective sizzle reel that pushed DVD sales and pay-per-view buys during this era).

Even when you take into account the lowered expectations that nearly any other Chamber win is not also a historic comeback by a performer many considered to be the best worker in the history of the company, there weren’t nearly as many “moments’’ in Chambers that involve the crowd the way the very best moments WWE produces have a tendency to. Goldberg mega-spearing people through the “BULLETPROOF” glass in 2003 and all of the different variations on that motif, for instance, while absolutely awesome, were rather intimately shot and focused on the two performers as opposed to on the crowd’s reaction as a whole to the spot.

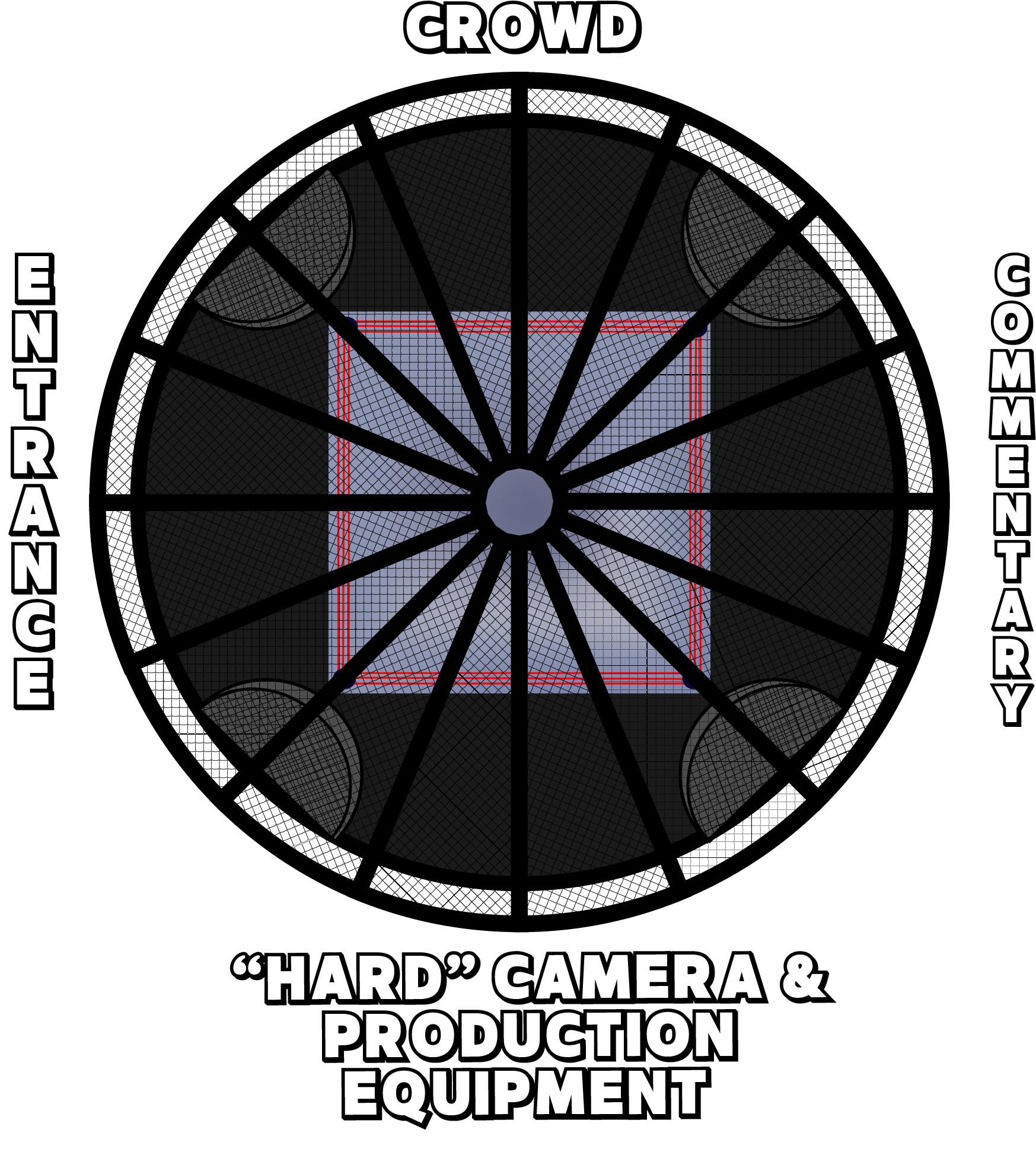

That’s because, on top of the original version of the Chamber being difficult to see through—which became much less of an issue starting in 2008, thankfully—unfortunately for WWE, in most other buildings in which they perform, the lower and upper bowls (as opposed to the moveable floor seats they add) usually prevent this kind of framing (an issue that would at least partially lead to the redesign 15 years after the first match). As such, for literally every other arena WWE has worked in over the last 30 years (at least when fans were present), the ring has a specific layout for how the show is presented from a structural and production perspective, that looks something like this:

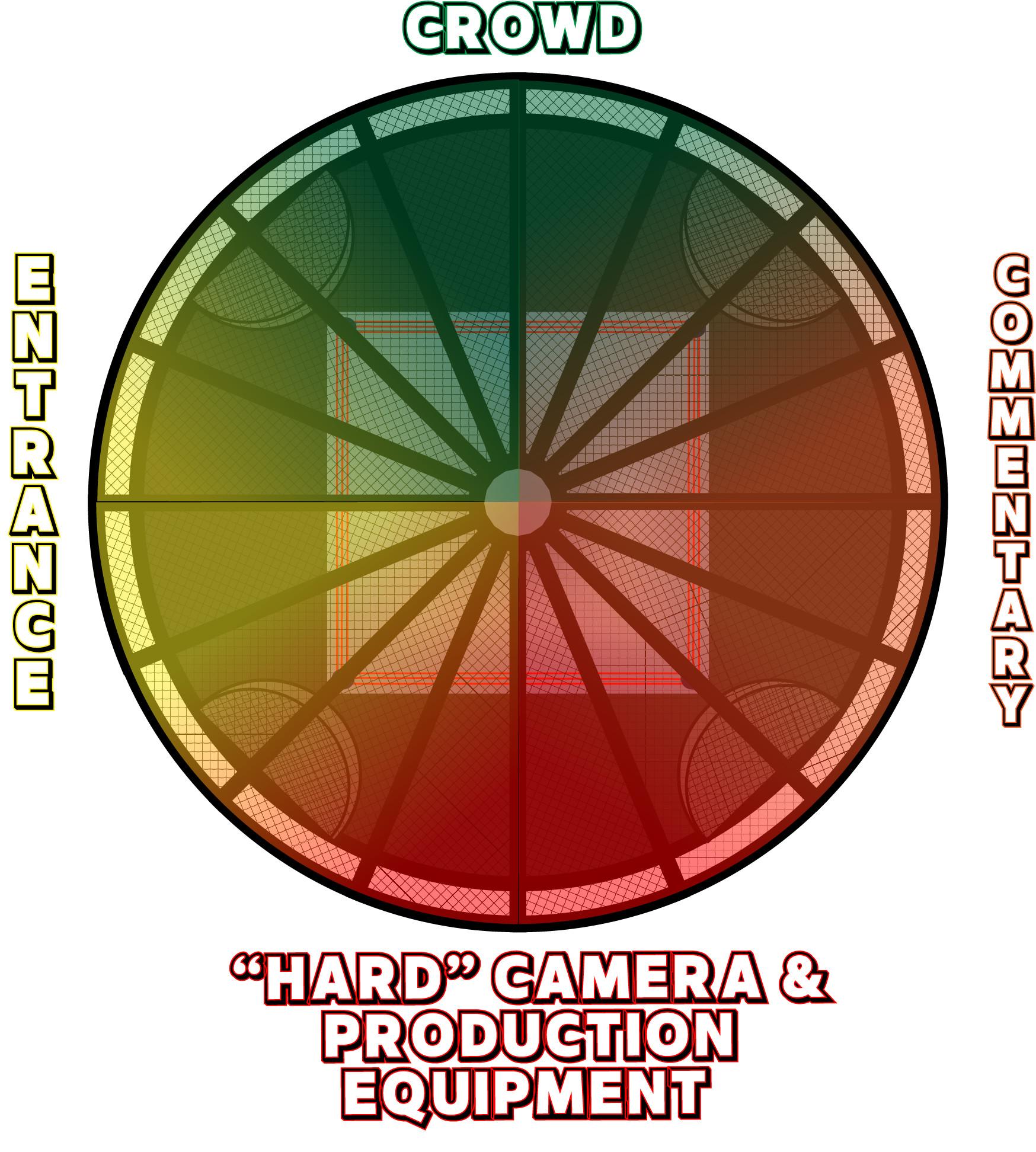

You may have intuited (especially if you didn’t have any strong interest in staring at camera equipment or Corey Graves’s wildly diminished suit game) how this poses a problem, both visually and logistically, for some of the pods/sections of the structure. This becomes even clearer if you split the chamber into “visual quadrants” based on the desirability of having the camera pointing at that side for an extended period of time:

As you can see, the top two pods are both what you might consider “good” places to have your camera pointed, while the third pod on the bottom left isn’t necessarily “bad” but is definitely boring (even now, you mostly just get a giant screen that says ELIMINATION CHAMBER, in case you’d forget you were at or watching an Elimination Chamber PLE during an Elimination Chamber match). But that fourth pod? We don’t know for sure what would happen if you pointed the camera in that direction for too long, but we’ve also seen the H-bomb scene from Terminator 2: Judgment Day and there’s no evidence to make us believe the result would be any different.

This is probably why the first two matches start with this pod—Chris Jericho (who is also, in part because of his record eight appearances, the all-time leader in eliminations by a decent margin, with 10) in the first match and Randy Orton in the second—before the rest of the wrestlers come out of theirs clockwise. This removed any suspense regarding that pod (beyond it being used as a weapon itself) and, by extension, any need to point the camera back there, which they did briefly during the match and seemingly instantly realized how unnatural it felt, spending much of the rest of the match looking literally anywhere else.

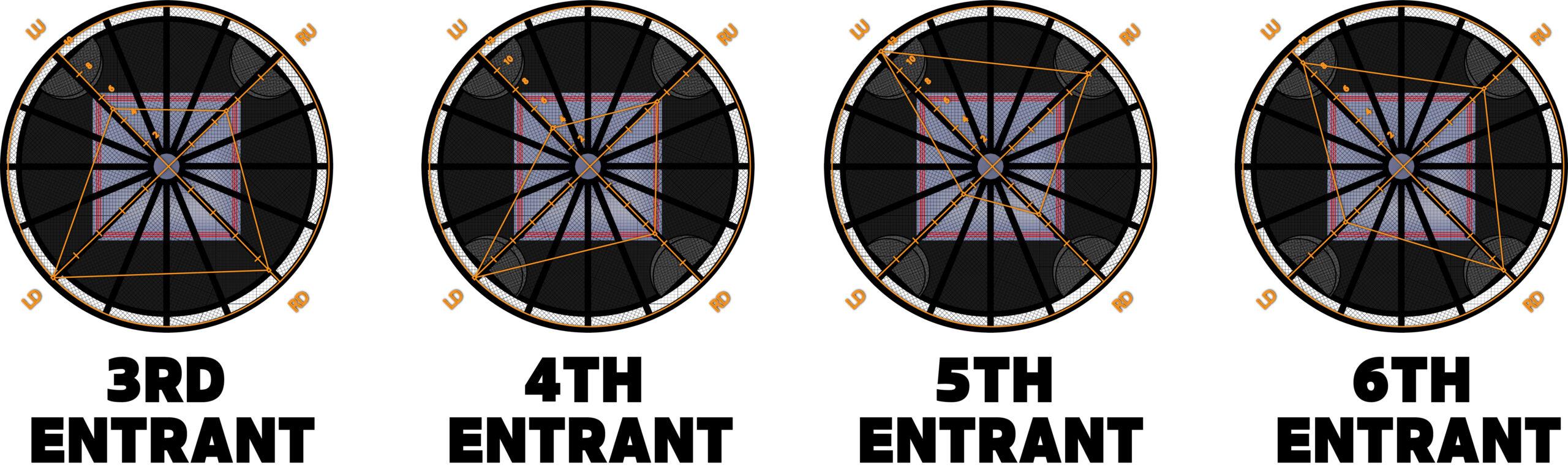

That would all be well and good—it’s not like I was personally offended when I realized—if the match itself wasn’t built around “chaos” and “randomness”; unfortunately for WWE, “random” doesn’t mean “the order in which the performers enter the match is determined by which corner of the ring they are standing in relative to the hard camera.” But it definitely was, and in embarrassingly obvious ways, too.

For totally practical reasons—people like games of chance, that’s just the way it is, was, and always will be, and they especially love mildly suspenseful synth music and goofy visual tricks when playing them (which is basically how slot machines make money)—WWE basically played the “final answer” music from Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? and had the spotlight operator pretend to do eenie-meenie-minie-moe with the pods. While WWE has been accused of thinking its fans were dumb since time immemorial, even they found the whole thing a little too on the nose, and as a response WWE decided to course correct.

Kind of. Instead of treating all pod people equally, WWE began to use the bottom right pod as a dump spot, which is how you end up with this:

As you can see, of the first 19 matches in the original Chamber, just TWO have been won by someone in the bottom right pod, and that someone was named Triple H, who won twice from that position as part of his record four times overall, including the third match, which was his second consecutive win and also the first not to release participants in the exact same clockwise order, though they just went counterclockwise instead.

This is done for, again, very obvious aesthetic reasons, but the lack of victories by those in the right pod has at least something to do with the ways in which the pod layout wildly skews the order in which people come out. (Yes there’s another graph.)

Haitch would manage to overcome the disadvantages to win it from this position again in the second Chamber match of No Way Out ’08, which was also the structure’s first night shot in HD, but it would be another 15 Chamber matches and almost 10 years before Roman Reigns would win.

This time in the new structure, which (as you may have been able to guess based on the chart) is even a bit more restrictive in terms of how undesirable the bottom right part of the Chamber is to be seen on-screen.

And that match (like the first H “down-right” win, where Evolution drama dictated the order in which performers would be released) even had a reason for Roman sitting in the Pod of Death: With the idea of feeding Braun Strowman to Roman, and in order to create the tension/suspense with Braun, WWE put the Monster Among Men in the top left pod (because although outcomes are roughly the same for the two top pods, the top left pod is more likely to appear on-screen), looming over the action until it was his time to let slip the dogs of war. He did, entering sixth and eliminating five other competitors (there were seven total in this one).

And, before WWE even had a chance to do any of that, it needed an establishing shot of Roman Reigns standing diametrically opposed to his biggest threat (a shot the cameras went to more than once), hence his position in the bottom right of the screen. Outside of making its most important performers look strong, WWE has essentially spoiled at least one part of the match every single time it lowers the Chamber.

WWE has also made it such that, for obvious narrative purposes, you are equally likely to win if you start the match (although they are technically “first and second” entrants, we count them as a single unit) or if you are the fifth person to enter (both spots have seven wins, two behind sixth for the most). This would make sense if something resembling the same courtesy was extended to the third entrant, who has won just three (the previously mentioned two by Triple H from the PoD, and in what was essentially a xenophobic fever dream, Jack Swagger in 2013).

Of course, that’s at least partially because WWE also goes out of its way to (for all the reasons discussed above) leave the top two pods occupied until the last two entries as often as possible. It would also be fine if those were filled by random, or at least random-adjacent, performers instead of what WWE actually did, which was essentially to treat those pods like a wing of the WWE Hall of Fame.

HBK, Goldberg, Edge, Kurt Angle, Big Show, Finlay, JBL, John Cena, Rey Mysterio, Kane, Randy Orton, The Miz, Daniel Bryan, the New Day, Ryback (who won, was an ENORMOUS star at the time, and looked well on his way to a major main event career), Sasha Banks, Jeff Hardy, AJ Styles, Brock Lesnar, this year’s Women’s winner Asuka, and this year’s Men’s MVP Montez Ford all started in the top right pod. Even absolute cannon fodder like Baron Corbin and Elias were explicitly put in this pod to generate heat throughout the match.

On the other hand—or I guess in the other pod?—this is what the historical roster for the bottom right looks like: Jericho (who had one exactly one world title to that point), Orton, Triple H, Chris Masters, Punk, MVP, Vladimir Kozlov, Mike Knox, John Morrison, Big Show, R-Truth, Dolph Ziggler, The Great Khali, Kane, Daniel Bryan, the Prime Time Players, Mark Henry, Mickie James, Roman Reigns, the IIConics, Kofi Kingston, Lucha House Party, Liv Morgan, Jey Usos, Sheamus, Rhea, Nikki Cross, and Bronson Reed.

While all these folks are talented performers, with more than a handful of Hall of Famers, it’s clear where the juice is, from a narrative and visual perspective. And it’s understandable that all of these production logistics may seem like little quirks that someone who watches these things way too closely might pick up on, while other stuff is almost certainly a consideration made as part of every other show WWE produces.

But these specific issues—all of which seem to stem from not really thinking through most parts of the presentation for at least the first half decade and then making it up as they went along the way—and the sheer number of them, basically guarantees the fans don’t actually get the feeling that “anything can happen,” at least in a narrative sense. (These issue range from “not being able to show a full quarter of the Chamber on TV” to “not actually having it be significantly more likely that the first person or the last person in will win, unless their pod is too close to the camera equipment.”)

In the Royal Rumble, while we have a basic idea of who will win, anyone can lose, as there is an expertly crafted sense of genuine surprise baked into the concept, not just because WWE has told us there is, but because it’s actually put its money where its mouth is basically since introducing the concept to the public. Hogan was eliminated in the first Rumble, Mr. McMahon beat “Stone Cold” Steve Austin in 1999, and, hell, even Alberto del Rio was very nearly eliminated at the end of the largest (actual) Royal Rumble in history by SANTINO MARELLA.

With the Elimination Chamber, what happens in the match may be surprising and exciting, but it’s very rare that any of it reaches exit velocity to matter in story lines going forward. In many ways, the Chamber is simply used by WWE to reduce the number of available main-event story lines in order to prepare for the WrestleMania endgame.

This is the fundamental problem with the Elimination Chamber and the reason it just feels like it matters so much less than anything else that WWE produces at this level. As a narrative construct, it has been without an actual raison d’être from the very beginning, and unlike a gimmick with purpose, like Hell in a Cell—which was a concept specifically promoted as a way to keep D-Generation X out of the Taker-HBK title match at Badd Blood, and was largely done in reality to let Kane rip the door off a presumably impenetrable cage for his debut while also evolving past the traditional cage match—the Chamber is a concept that insists upon itself.

And, while it’s certainly cool looking, this has left the Chamber matches themselves, as a general rule, to only be as good as their participants and the stakes involved. This is where WWE has, and still does, find itself often struggling to make the Elimination Chamber carry nearly the cachet of the other long-term gimmick matches it has produced, like Money in the Bank (which the Chamber debuted several years before), the Rumble, and even the aforementioned Hell in a Cell.

At this point, the Elimination Chamber is officially old enough to buy a drink and still hasn’t figured out even the basic ideas about what it wants to do with the rest of its life. In the last 10 Chamber matches, six different things have been at stake: the Women’s Tag Team Championship, the WWE Championship (3x), the SmackDown Tag Team Championship, a Raw Women’s Championship match at WrestleMania (3x), an immediate match for the Universal Championship, and the United States Championship.

Now, things have changed in major gimmick matches before. As we discussed just a few weeks ago, the Royal Rumble went through a number of permutations before setting a standard set of rules, regulations, and expectations for fans and the company alike to either adhere to or subvert in an attempt to tell specific stories at specific times. But for the Rumble, or pretty much any gimmick match lacking a physical structure (outside of a ring and, maybe, a ladder), the investment in putting an innovative show on (or changing the way something worked) was a matter of opportunity (and not material) costs.

The Elimination Chamber started off, however, and has felt since, like WWE trying to score five runs in one at-bat. Already coming off the emotional and financial high of the Attitude Era, and almost certainly seeing the Elimination Chamber as a big swing to attempt to make its way back to crossover pop culture relevance while waiting for the other shoe to drop on the revenue numbers after the departure of Stone Cold and The Rock, there never seemed like a good enough reason for the company to even take the bat off their shoulders.

While the first match was a home run (and I swear, the baseball metaphor ends here) the batting average on genuinely great matches, or even matches that really live up to the promise that the concept feels like it should have, has at best been almost replacement level. Since introducing the new Chamber, which was built with new features—including a much larger opening up top for dramatic “there are bodies everywhere” shots from a ceiling camera, glass corners, and no curves to allow as much light (and space for cameramen) as possible to get into the cell for filming and to make it easier to set up in every arena —it seems like whoever designed it was aware it would be on TV, while the match itself became noticeably more watchable in a narrative and physical sense (I know you all had great concern for my ocular health).

More than that, WWE has also begun to give the show itself a deeper sense of purpose as the Official Last Big Thing That’ll Change Things Before WrestleMania show. Over the last decade, the Elimination Chamber show proper had been stuck in limbo between allowing the fans to actually understand what was going to happen on the WrestleMania card (which in turn made the matches we had just watched on the show feel like they mattered) to acting as a post-Rumble palate cleanser for whatever road-work-themed PPV WWE would put as the last roadblock or fastlane on the Road to WrestleMania™.

Now, with what appears to be a massive drop in the number of shows that will be run every year (while there is a Backlash announcement, as well as a King and Queen of the Ring PPV, it doesn’t seem like we’ll be getting any end-of-days-themed PPVs or random gimmick shows shoehorned into the schedule), every platform like this becomes more valuable. While we’re obviously in the bag for Asuka in the Palace of Wisdom, Austin Theory’s performance in this year’s match for his U.S. Championship managed to overcome its (somewhat) diminished stakes to provide a highlight match of the year so far and positioned as ready for whoever comes his way (regardless of whether he sees them coming or not).

Which is what the Elimination Chamber’s purpose should be. A thing that matters because a lot of people put a lot of work into it, but also because WWE seems to know and care what it wants to do with it. The Purpose Driven Life may be a bad book, but it’s a significantly better booking decision than whatever you might have wanted the alternative to be.

Nick Bond (@TheN1ckster) is the cofounder of the Institute of Kayfabermetrics and provides weekly updates to The Ringer’s WWE Power Board.