I remember when I first bought the condo right on the beach surrounding Anoa’i Bay. There was a sense of peace as I watched the better part of two and a half years go by while the world returned to “normal,” and stadiums started to fill with the sounds of bodies slamming against mats while thousands of folks shared in the communal experience of the most beautiful, dumb thing humans have ever created.

Lately, though, there’s been a lot of big talk happening here that has made me desperate to get off of Roman Reigns’s “island of relevancy.” That was before I realized how far away it was from civilization, or any kind of reality, as more and more people found themselves drunkenly stumbling in from Heyman Harbor (“Where the beer and lies flow like wine, which also flows like wine,” as the locals say). When paired with a sanitation department that has been on strike for the better part of the last year, escape has become both more important and seemingly more impossible every day.

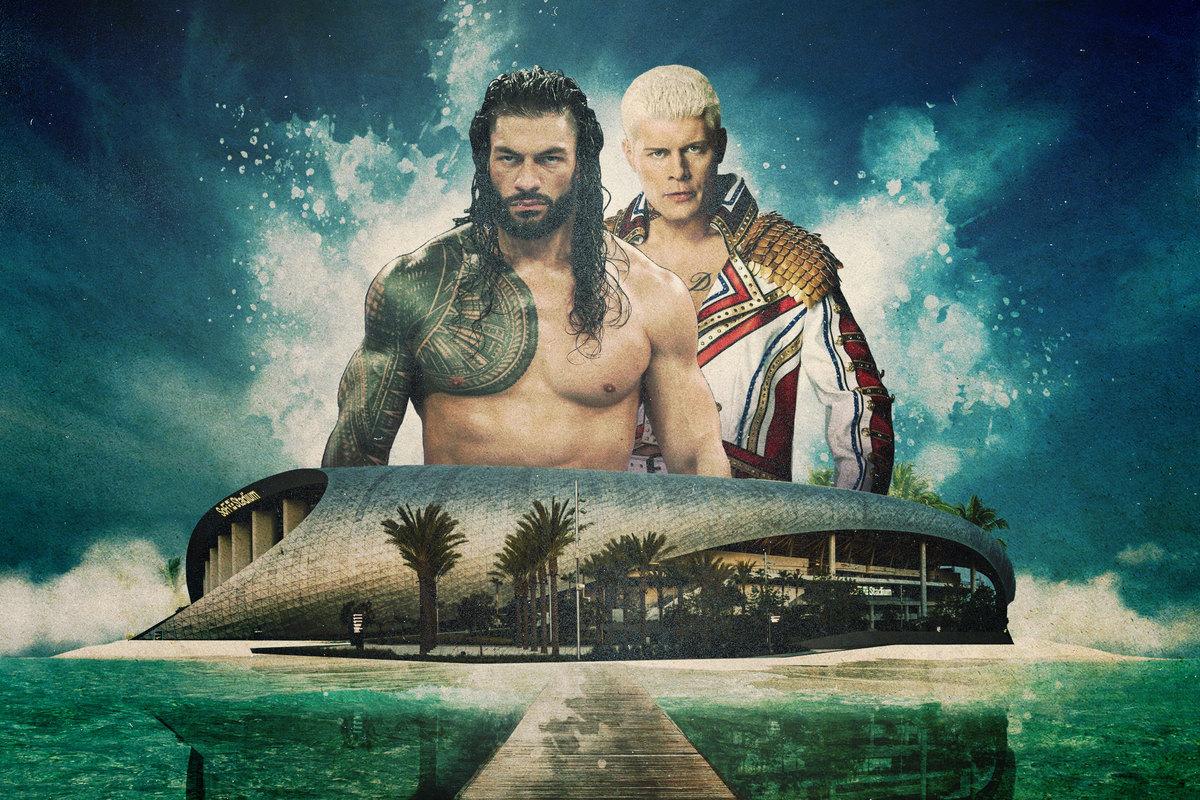

And as your dutiful correspondent, it’s become a moral imperative to at least get to the highest point on the island, even if it’s a pile of bullshit a mile high, to get a full survey of the land as we make our way to WrestleMania, where, hopefully, rescue crews will begin evacuating the folks still stuck here. But, since it’s going to be a bit of a journey to get to that point, let’s start with the lowest-hanging fruit possible to get us rolling with the right kind of energy:

Can any of us sit here straight-faced, under the watchful eyes of God, and truly say that the whole of WWE’s SmackDown—and not just its Bloodline scenes—deserves an Emmy? More than Succession? Or Severance? Squid Game? Stranger Things? Yellowjackets? Better Call Saul? Ignoring, at least for the moment, quality (though, c’mon), these shows all tell stories with boundaries that hew significantly closer to the full breadth and width of the human experience than basically anything you will ever see on even the best wrestling show.

OK, maybe not all of these shows do the whole “breadth and width” thing, but even the ones that don’t and definitely wouldn’t care to, like Succession, are at least pantheons of great TV and make a compelling case for a wealth tax (and, like, a Purge, maybe two). Even something a little bit more apples-to-apples with the Bloodline’s story, like Ozark—which, instead of having one character treating his wrestling stable like he’s running a drug cartel, features an actual drug cartel and Jason Bateman—is able to do so much more on its worst day than wrestling can on its best day because of the inherent limits of both live television and the medium of wrestling.

These are also both the exact kinds of shows that highlight that no meaningful stakes exist in the world of professional wrestling, even in kayfabe. Beyond the wrestling and the prestige and fame that come from being good at the wrestling, unless Matanza and Dario Cueto are involved, the concerns of those involved are far from existential. And because playing a role on a show is a fundamentally different concept than a wrestler working a gimmick, there’s not even a real concern about being written off the show in a meaningful way unless you fall ass-backward into a Loser Leaves Town match.

Now, you’re probably saying, BUT WHAT ABOUT THE ACTING? And, yes, various members of the Bloodline have done a spectacular job of acting compared to other professional wrestlers. However, anyone who has seen more than a handful of Botchamanias (or, better yet, any Wrestling is Awesome segment of an OSW Review episode) can attest that “These are some of the best actors in wrestling history” is not saying very much at all.

This is why although I wouldn’t laugh at Rami Sebei (Sami Zayn) if he wanted to submit clips for something like the Outstanding Supporting Actor category (he’s done a Batista-level job in some of his “scenes,” the highest possible compliment you can give a wrestling thespian), I’d understand that he’d have a less-than-zero chance of getting nominated ahead of performers like John Turturro or Christopher Walken (yes, the Christopher Walken) just from a logistical standpoint. In fact, it’s precisely these “for your consideration” concerns that make this entire argument so absurd on its face that you have to assume that it’s not a realistic assessment of the situation.

Instead, it’s basically what you say when the idea that “These things are good things, and good things can win awards for which they are technically eligible” is one of the major ways in which you interpret the quality of the art you are watching. This is totally understandable and why, ultimately, this conversation is good, clean fun: As wrestling fans, we rarely have something to sink our teeth into on an emotional level beyond really hating one guy and liking the other, so if someone wants to throw a parade or hand out awards when it happens, so be it. Also, nothing would make the VenPurr Bros. happier than seeing Sami in a tuxedo doing the Sami dance on TV’s biggest night.

What’s truly bothersome is the way this almost total detachment from reality when evaluating the Bloodline has permeated into wild discussions about this story’s place in the history of wrestling, where it has somehow fallen ass-backward into “greatest story line ever made” territory. To that, I have to say: We used to build things in this country, and some of those things were wrestling narratives that actually exemplified what wrestling could be and not just the wrestling version of ... literally every story of absolute power corrupting absolutely.

But because the Bloodline as a concept is built on the rather obvious foundation of a largely unadulterated truth—Joe Anoa’i (Roman) really is cousins with twins Josh (Jey) and Jonathan (Jimmy) Fatu, they come from an EXTREMELY prominent extended family of wrestlers, and they did seem to grow up close enough to “together” for it to pass in the story line as “real,” or at least as “not total bullshit”—we have a tendency to ignore that essentially everything that has happened within that context is clearly a part of the constructed reality of the wrestling show we’re all watching.

And while a narrative playing into “Is this a shoot?”–style storytelling is not necessary or sufficient criteria for “determining” whether or not a story line should be considered great (and has very little to do with whether or not the story being told is enjoyable), very few of the best stories told in wrestling history have had so little to do with the world surrounding them. More so than even the action in the ring, the interplay between our reality and the unreality of professional wrestling is the definitive trait inherent to the medium that makes wrestling, well, wrestling, which seemed to be something that was (pardon the pun) acknowledged at the beginning of this story line.

However, whatever real tension might have existed from either residual teenage angst—as you may remember, the main emotional through line for the first six months or so of this run was focused on the tension between Jey and Roman, which seemed to stem from Joe picking on and ordering around Josh and Jon for much of their childhood—or professional resentment the Usos might have had toward Reigns’s success was largely dealt with more than two years ago. Jey and Roman’s interpersonal dynamic at the time (and their Hell in a Cell match at 2020’s titular PPV, in particular) touched on the core emotional conflict and tried to engage with generational trauma and the expectations that family and legacy place upon us, but that concept has not been reintroduced in any palpable way.

That was easily some of the best television ever produced by WWE. Had they committed to telling the story of the Anoa’i family in its totality with the same level of care and focus, we would all be on a very different path. However, over the past year and a half, the story has quite literally lost the plot (or at least that plot). Now, its emotional crux has been whether or not Jey would accept (and then eventually side with) Sami Zayn—a guy who he’s been kayfabe friends with for a couple of months—over his twin brother simply because their cousin sucks.

Why? Because when fans came back and saw Roman turned heel, the Bloodline got over. Like, crazy stupid bananas over. And while great wrestling television has come out of it—though your mileage may vary on Jey’s “acting,”—by taking their foot off the gas on Roman’s unmitigated jackassery (to make him more palatable to fans on the fence about “acknowledging” him and to sell GOD-awful T-shirts), they’ve steered themselves into a bit of a narrative dead end, where the goal becomes “prolonging the magic” instead of “telling the best story.”

This has led to a recurrence of the Four Horsemen of the FUN-pocalypse problem, where your objectively very evil but popular faction doesn’t meaningfully lose their sinister side, but the reasons behind them doing sinister things become “shrug emoji” instead of the characters involved being shitty/evil people. The Horsemen bit, which began in earnest after one of them broke Dusty Rhodes’s leg in a cage at the Omni, actually started as a kind of “Lost Cause” revival between Ole Anderson and his kayfabe cousin (as well as the greatest wrestler of all time) Arn Anderson. The “big bang” moment for the Horsemen occurs when Ole—in an interview in which he essentially makes a backdoor case that’s supposed to half sound like he’s advocating for (I swear) the reintroduction of segregation as a way to explain why he wants to end his tag team with Thunderbolt Patterson—cites Arn’s recent debut for the catalyst for making him realize he’s “gotta go back in time.”

And yes, they do play Michael Jackson’s “Beat It” as Manny Fernandez’s entrance music for his match against Arn in the second half of this video, because Crockett-era broadcasters didn’t care about royalties, and, as such, the vibes were immaculate.)

Eventually, this extremely rough edge would be sanded down as the Horsemen got increasingly popular and their nefariousness went from “mildly racist, extremely violent group of marauders” to “guys who helped Ric Flair retain his title.” This is exactly where Roman and the abusive hold he has over everyone in his orbit, along with the pie-facing by which it is made manifest, find themselves. Having become the ol’ “semiotic means to a narrative end,” Reigns LOSING control OF THE VOLUME of his VOICE has started to function in much the same way “Flair befriending and turning on someone” worked, where his outbursts don’t really add actual intrigue or depth to the proceedings and instead become the wrestling version of “playing the hits.”

Thankfully, much of the narrative juice—the thing that actually moves the needle every week in terms of character and story line development—has shifted toward the Usos, who kind of sit in a parallel universe with Sami and his soon-to-be tag team partner (again), Kevin Owens. That Roman Reigns appears to be too busy to show up for every episode before what’s supposed to be the biggest show in the history of the company has actually benefited the story line, as Paul Heyman plays proxy better than Roman Reigns does anything, other than serve as the poster boy for the power of veneers. (To be clear, not just because I’m a wrestling writer who looks like he writes about wrestling, but that’s not meant as a dig in any way—his smile is INCREDIBLE now and he even seems more comfortable with it than he used to, so good for him.)

Even Cody Rhodes’s appearance to make the save for Sami on Raw—and challenge the Usos to a fight at the end of SmackDown—wasn’t really about Roman. It was vamping to build anticipation for the inevitable reunion between our two favorite Quebecois wrestlers. (Sorry, Raymond. Jacques, you know what you did.) That it has established Rhodes as standing in opposition not just to Reigns, but to the Bloodline’s raison d’etre—somewhat selfishly, as you remember Cody’s song doesn’t say shit about there being “more than two royal families in professional wrestling”—and their role in WWE as a malevolent force is great but was very secondary to the actual happenings in front of us.

And while a story like the nWo would eventually turn from hot shit in a champagne glass to cold diarrhea in a Dixie cup, as opposed to the Bloodline, which has gone a bit stale but remains main event–worthy, the initial year-and-a-half run of the New World Order (essentially through Starrcade ’97) is as significant (both in wrestling and the larger culture) a story as has ever been told in the history of the medium. In part, because it marked a massive shift in the ways stories were told, not just from a writing perspective, but also from a cinematography perspective.

And, I mean, that turn:

More importantly, though, it worked as well as it did because everyone involved had actual motivations and real character depth that moved the plot forward. Now, Hulk Hogan stinks on ice—we say that in a way that isn’t legally actionable, we hope—but he is one of the most over acts in history and it wasn’t by accident. For all his many faults, Terry Bollea played something resembling a nuanced, almost three-dimensional character (or, OK, at least a person with an interior life who had wants and desires, as well as interests, outside of wrestling. Mostly “hanging and banging” then riding Harleys with “Brother Bruti,” but interests nevertheless).

With the Bloodline, Roman wants to stay champion and is willing to do whatever it takes. That’s ... about it. As mentioned earlier, at some point he conflated that with being able to provide for his family and secure their (impressive in its longevity but not disproportionately successful at the highest levels) legacy, which was dope. But that motivation has largely dissipated and hasn’t been replaced by an equally compelling reason for Roman to be so obsessed with holding onto the titles.

Hogan did his turn, then became champion because he knew that whoever holds the gold holds the power. Roman got the gold (again) because his self-worth is tied up in his titles and the championship belts that accompany them, or at least that’s what it feels like, but even that level of introspection or characterization seems to be missing. And what’s more is that Hogan’s reasons for turning against WCW were understandable: Fans had largely abandoned him (which, having seen him work, I get it) and he had no actual loyalty to WCW, merely seeing the company as a chance for a hefty paycheck (in the same way the company saw him as a meal ticket). So, when the opportunity arose to become part of a dominant faction, there was no real reason for him to not make the decision he did.

With Roman, it’s about as deep as “He’s not a Good Guy, he’s a Bad Guy who is obsessed with being the Guy.” This speaks to the larger problem of the Bloodline story line: there really isn’t much nuance or introspection with the decision-making in the story, or to anything that’s happening. And, no, Jey making the “uh-oh, puppy did a poopy” face every time Roman is mean to him isn’t the same as nuance.

No one’s expecting “The Suitcase,” but some kind of internal conflict (usually between the person you are and the person you want to be) is often part of what makes truly great stories. Like the Mega Powers (sorry for all the Hogan) or almost literally every show and movie that’s ever been awarded for its excellence—except whenever the Academy sees a movie that explains how racism was solved by the invention of the automobile—having the ability to argue either side of a conflict (if not necessarily either side’s reaction to the conflict) is a key component of their success.

While Randy Savage’s reaction to Hogan’s behavior was the catalyst for their world-famous explosion, Hogan was (as the kids say) sus AF and even Miss Elizabeth could have told Hulk to cool out (or at least say less). Roman’s reaction to everything—Sami chants, most notably, but basically any time someone doesn’t say exactly what he wants to hear—hits the “I think you are trying to steal my girl and my championship in between all your hotdogging and grandstanding” level that Savage only reached at WrestleMania V. Which, in theory, would put the onus on everyone else around him to decide whether or not to bust Roman’s head open for habitual line stepping, but it’s happened so frequently that it seems increasingly unlikely anyone ever will.

Some of this is structural and requires watching a lot (some, including my wife, would say “too much”) of wrestling to pick up on. As a bit of a spoiler, I’ve been watching every WWE PPV main event (in preparation for a WrestleMania project which may kill me) in order and, outside of the, uh, enhanced look of the overwhelming majority of the competitors, the most shocking aspect to this journey into that particular heart of darkness is the ways in which the earliest PPVs showcased a product that was morally ambiguous with a presentation which engaged in actual discourse about the roles of morality and ethics in a ruthlessly competitive space like professional wrestling.

It didn’t hurt that Jesse Ventura, the greatest heel announcer of all time—we will not be taking questions on this subject, but the answer to all of them is “you’re wrong”—and maybe the only true practitioner of what I like to call “courage of your convictions” commentating, was in the booth for most of the major shows in the company’s first five years of PPV. Ventura was quick and smart enough, with the required amount of stroke and on-screen credibility, to truly plant seeds of doubt in the minds of free-thinking viewers that maybe the bad guys had the right idea all along. Or at the very least, the “good guys” were as full of shit as anybody else, but had the backing of the company and the fans to better hide their ugly sides. (He also once explained what a rest hold was doing in kayfabe terms as seamlessly as I have ever seen a professional broadcaster do anything in my entire life.)

Unlike his spiritual descendants (see Graves, Corey), Ventura wasn’t framed as the wrestling equivalent of right or left, but someone with a different perspective than his either largely neutral (with Vince McMahon and Tony Schiavone, the latter of which is the greatest commentary team of all time, and please see earlier instructions regarding discussing this) or comically pro-babyface (with Gorilla Monsoon, also Schiavone when the Ultimate Warrior was involved) broadcast partners. Now, the idea is selling you (even in the “New and Improved!” Triple H era) on what’s happening at this moment being the greatest thing ever (despite us having access to the Network and, thereby, knowing for a fact that it isn’t) with a specific vision for how you should react. Commentators don’t have meaningful conversations, even in kayfabe, about what’s happening in the ring as much as they produce point-counterpoint cable news pundit banter.

This framing—when coupled with (outside of Brock Lesnar and whoever is the designated monster [read: tall] villain that fiscal quarter) heels that range between Team Rocket and villains from Batman: The Animated Series levels of competence—means that anything resembling high-level professional acumen by the bad guys gets treated as almost black magic, simply because we’re so used to heels soiling themselves the second they are confronted by adversity or someone willing to stand up for themselves that not actively sucking is seen as “smart booking.”

But this is just as much about Stockholm Syndrome as it is the way the show is now presented narratively. After years and years of categorically rejecting Reigns, it seems him showing flashes of the character we always wished he would be was enough for a sizable chunk of the internet discourse (and a depressing number of fans in the arenas) to start treating him as a conquering babyface. As opposed to what Reigns is: a bully and cheat whose obsession with, and stranglehold on, power has warped the world around him so thoroughly that those once connected to him are now trying desperately to save everyone else in his inner circle from turning into the monster he’s become.

Which is the ultimate failure of this story line at this point. Reigns is unequivocally an abuser, the villain, the antagonist, and the final boss at the end of the game or however you want to describe this interminable run holding the company’s titles hostage. He is not the hero, and yet there is way too much support on his end of the ledger, considering there has not been a legitimate reason to root for him since he tried to kill his injured cousin to win a wrestling match against their twin brother, who he then threatened to excommunicate from the family the next day unless he fell under his thumb.

The shockingly positive reaction to Roman’s completely out-of-pocket behavior—and a realization that most people don’t have a meaningful grasp on what the word “betray” means—has gone a long way in sucking the fun out of this narrative, at least in the Palace of Wisdom. Instead of enjoying the culmination (hopefully) of the second act of one of the better bits of long-term wrestling storytelling produced in the past 30 years of professional wrestling and appreciating it for what it is, we are forced to sit here, speaking in hyperbolics.

Like pretending that a story line that essentially asks “What if Tony Soprano was written to appeal to the sensibilities of children?” is the greatest piece of literature in the modern world. Or even more egregious, trying to convince ourselves Reigns has somehow made his way into the discussion of greatest wrestlers of all time—or, even more hilariously, and easily disprovable, the greatest champion of all time—when in reality, it’s exceedingly difficult to be considered the best at something when you’re the third-best guy in the only two factions you’ve ever been a part of and half your record title reign has been holding a belt no one cares about.

But that’s a discussion for another day. How’s Thursday sound?

Nick Bond (@TheN1ckster) is the cofounder of the Institute of Kayfabermetrics and provides weekly updates to The Ringer’s WWE Power Board.