Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: The CEO of a popular social media company walks into a congressional hearing, sits down in front of a bunch of cantankerous lawmakers, and gets treated like a political punching bag. The complaints go something like this: The platform violates user privacy. It’s addictive, psychologically damaging, and dangerous for kids. It’s both too “woke” and overflowing with hate speech. It’s vulnerable to disinformation and foreign interference. It works in ways that House members don’t understand, but they know they don’t like it all the same.

The CEO meets these grievances with vague promises of reform and an unlimited supply of I’ll get back to yous. By the time the hearing is over, it’s clear that this was primarily an exercise in political theater. The average onlooker doesn’t really believe there will be meaningful reform to how tech companies operate. And usually there isn’t.

It’s not a particularly uplifting ritual. But if you’ve paid attention to the ballooning of big tech over the past two decades, you probably know it by heart. A good congressional paddling has become a rite of passage for nearly every major U.S.-owned social network. Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram have all been interrogated on Capitol Hill, scolded for being devil-may-care data vacuums, and then released back to their natural oat-milk-rich Silicon Valley habitats to keep making everyone—including the lawmakers who questioned them—more money.

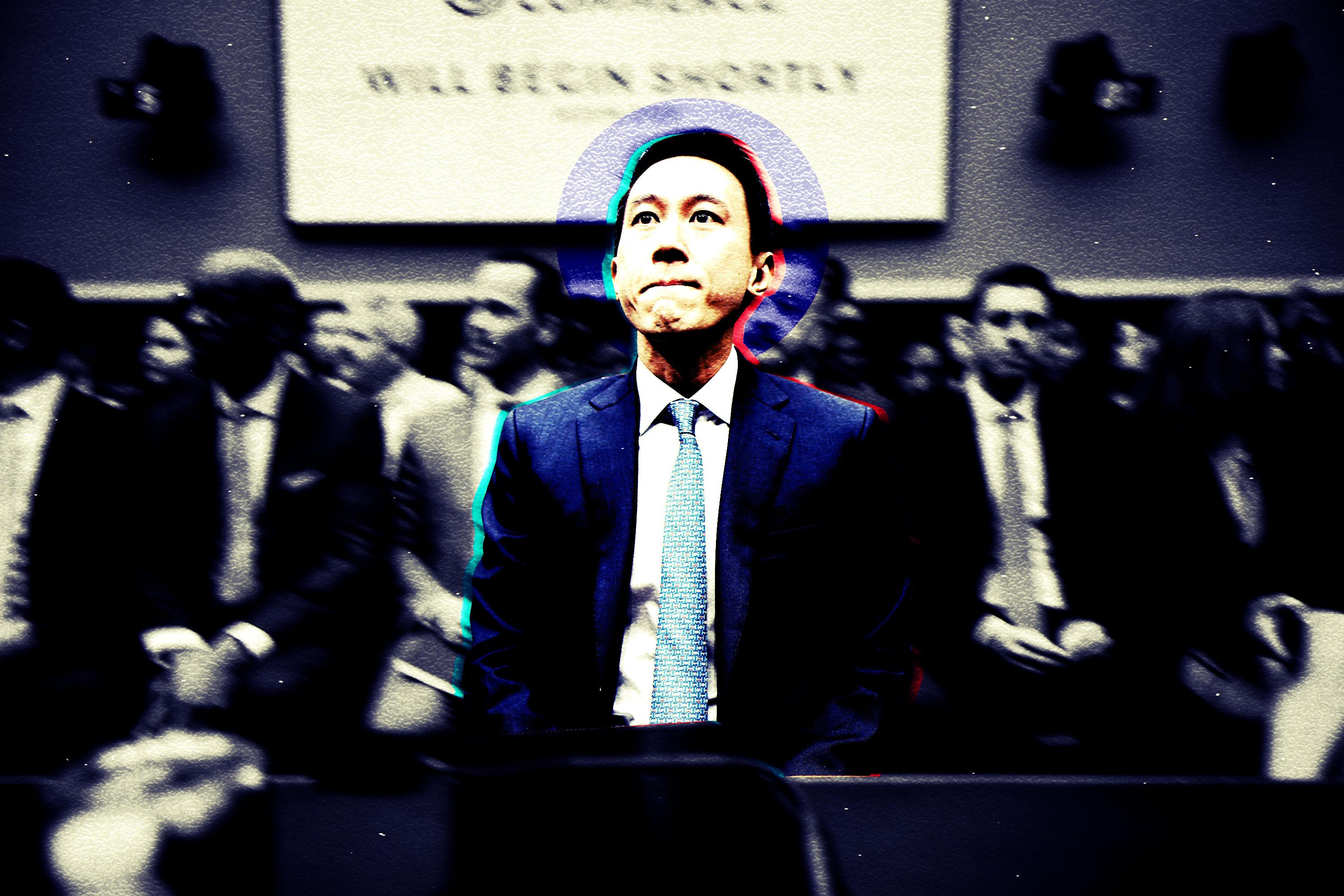

On Thursday, TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew went to Washington, D.C., and threw a wrench into this established tradition. Because—despite being an indisputable cultural catalyst that has 150 million monthly active users in the United States—TikTok is not an American product. The video-sharing app is owned by ByteDance, the privately held Chinese internet giant that is based in Beijing.

This detail set a fire under the typical congressional step-and-repeat, inspiring an opening statement that felt unusually aggressive and dismissive: “You are here because the American people need the truth about the threat TikTok poses to our national and personal security,” said House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Washington). She underlined concerns that TikTok collects “nearly every data point imaginable,” which the Chinese Communist Party is able to use “as a tool to manipulate America.” She cast doubt that TikTok would ever embrace “American values” for “freedom, human rights, and innovation.” She ridiculed TikTok’s plan (nicknamed “Project Texas”) to store all U.S. user data on American soil as “a marketing scheme.” Finally, she arrived at a conclusion shared by our two most recent presidents, that TikTok “should be banned.” Her mind had been made up before Chew ever got a word in.

The hearing as a whole followed a similar script. More than 50 representatives lambasted Chew for virtually every big tech violation under the sun, from encroaching on user privacy to harming the mental health and well-being of teenagers. Many of the reps’ talking points sounded familiar, as if cribbed from previous hearings featuring prominent U.S. tech executives. As Ron Deibert, the director of a University of Toronto laboratory that has analyzed TikTok’s data collection practices, put it on Twitter: “Concerns with TikTok should serve as a reminder that most social media apps are unacceptably invasive-by-design, treat users as raw material for personal data surveillance, and fall short on transparency about their data sharing practices.”

Though a few Democrats in the hearing offered up comparable rationale, the rare bipartisan fervor in the room underlined a clear, unspoken truth: When our companies guzzle data, it’s tolerated. When a Chinese company does it, it’s a national security threat.

This conflict has taken center stage in the ongoing geopolitical tension between the U.S. and China. The United States has a long, if inconsistent, history of blocking Chinese business deals while citing national security and human rights concerns (the most previously notable of which involved the Chinese communications company Huawei), and gripes against TikTok in particular stretch back to 2019, when its rise in popularity stirred bipartisan grumblings about its potential national security risks. Unlike other Chinese companies doing business in the U.S., TikTok is a social media app with real cultural cache, and has the power to influence the kind of media that Americans consume daily. Not only can it surveil Americans, but it can collect information about what they like, and potentially use that to launch disinformation campaigns as well.

At the core of legislators’ concerns both then and now is China’s 2017 national intelligence law, which broadly states that companies and citizens are required to “support, assist and cooperate” with state intelligence work if asked. The implication here is that if the Chinese government ordered ByteDance to hand over hundreds of millions of Americans’ data, the company would be compelled to do so. Chinese government spokespeople have challenged this interpretation of its law, saying that intelligence work is conducted according to local laws abroad. But given the country’s authoritarian leadership, sweeping citizen surveillance, and record of human rights violations, Congress is right to question the validity of that explanation. Having the power to collect detailed data, and use that data to influence what people see and believe, is the next political frontier. And it’s hard to deny that if the Chinese government had access to all the data TikTok collects, it really could use that to its advantage on the global stage.

Since initial worries about TikTok materialized in 2019, the U.S. government and the platform have been in the throes of a public back-and-forth not unlike the kind of snappy drama that regularly occurs on the app itself. In August 2020, then-president Donald Trump signed an abrupt executive order that banned the app. (The move may or may not have been inspired by an incident earlier that year, in which a bunch of K-pop fans on TikTok claimed to sabotage attendance of one of his campaign rallies.) This kicked off negotiations to reach an agreement that would both satisfy the U.S. government’s security interests and allow the app to keep operating on United States soil. Ultimately, the ban didn’t take, and TikTok went on to pursue “Project Texas,” a partnership with Austin-based Oracle that aims to move U.S. users’ information to domestic data centers and restrict access to that data abroad.

This was the focus of Chew’s retort to questioning on Thursday. He went so far as to question the American exceptionalism at the heart of the hearing: “I don’t think ownership is the issue here,” he said late in the session. “With a lot of respect, American social companies don’t have a good track record with data privacy and user security. Just look at Facebook and Cambridge Analytica, for one example.”

The Biden administration has conveniently chosen to ignore this point and doubled down on its opposition to Chinese ownership. It has moved quickly in recent months to protect itself from the possibility of TikTok data breaches. In late February, the White House gave federal agencies 30 days to delete TikTok from government devices. Canada, Britain, the European Union, and New Zealand also recently called for similar measures, and India banned the app entirely in 2020. At the start of March, a House committee advanced a bill that would allow Biden to ban the app. (You’ll never guess what it’s called.) Soon after, the Biden administration said that the only way to prevent a TikTok ban would be for ByteDance to sell it to a U.S.-owned company. On Thursday, the Chinese government said it would oppose a forced sale.

What happens next is anyone’s guess. If Biden does the equivalent of saying “Fuck it forever!” and bans TikTok in the U.S., he would likely face legal challenges over free speech violations. (Just as Trump did.) The administration could nevertheless place TikTok on a blacklist that would make doing business with the company illegal. This would leave a monumental void in the social media space, one that other tech companies are frothing at the mouth to fill. It’d also leave hundreds of millions of users who’ve adapted to using TikTok as a money-making tool in a state of limbo, and it wouldn’t address the larger user privacy concerns that have long gone unchecked in the tech sector.

Thursday’s hearing managed to both intensify and conflate two separate conversations. There may very well be legitimate national security interests in preventing a Chinese company from maintaining control of TikTok. But legislators’ concerns for their constituents’ individual privacy ring hollow when the U.S. government has so far failed to pass anything resembling a comprehensive privacy law that applies to misbehaving American companies and their data brokers. Many representatives may not be willing to take the political risks necessary to confront our tech sector hypocrisy, but they’re certainly game to whip out some flashy poster boards and put on a show.