Editor’s note: This story was originally published shortly before Killers of the Flower Moon’s world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival. We’re resurfacing it now as the movie begins playing in theaters.

David Grann’s latest nonfiction epic, The Wager, follows a heaving imperial British warship of the same name as it sets out in 1740 on a perilous mission in search of Spanish treasure. Like many of Grann’s stories, it’s a high-stakes quest that unravels in a setting that feels entirely divorced from modern society. After all, this was the Age of Sail, a time when navigating a ship involved a concerning amount of guesswork, and the best solution for a serious injury was often amputation. But ask Grann how he landed on the idea for the book and he’ll say it all began with the headlines of 2017.

“I was following the news each day,” Grann told me over the phone last month. “These battles over truth and so-called fake news. I suddenly was trying to find a way to get at some of those scenes. And somehow I found myself in the 18th century.”

A fan of both Herman Melville and long-forgotten archives, Grann landed on the journals of a 16-year-old midshipman who was stranded with his crew members on an island off the coast of Patagonia. It was not the document’s descriptions of typhoons, shipwreck, or mutinies, however captivating, that convinced Grann the story of The Wager was worth resurrecting. Rather, it was how the ship’s surviving castaways later described those events to the masses, publishing conflicting accounts of what happened to save themselves from being hanged.

“It was disinformation and misinformation,” he said. “There were competing narratives and there were even allegations of fake journals. Then I would come home and I’d be reading about the banning of certain history books. And I was like: This 18th-century story is also a weird parable for our times.”

It’s this extraordinary ability to connect the dots across nearly 300 years of history—to sneak modern-day allegories into intricate adventure tales—that has vaulted Grann’s work from bookshelves to silver screens. The bespectacled 56-year-old dad has long been a “storyteller’s storyteller,” appealing to a subset of readers who cherish the classics and nerd out on bibliographies. In his two-decade-long post as a staff writer at The New Yorker, Grann has tackled incredible deceptions, curious crimes, and grueling voyages with literary aplomb. In his equally impressive run as an author, his books The Lost City of Z, Killers of the Flower Moon, and most recently, The Wager, have risen to the top of the New York Times bestseller list and brought his excellent work to the eyes of the masses. As his stories have grown in detail and scope, so too have the films that have been adapted from them. In recent years, his name has become a buzzword among IP-hungry Hollywood insiders, some of whom even stay up until midnight on the eve he’s slated to publish a new magazine article.

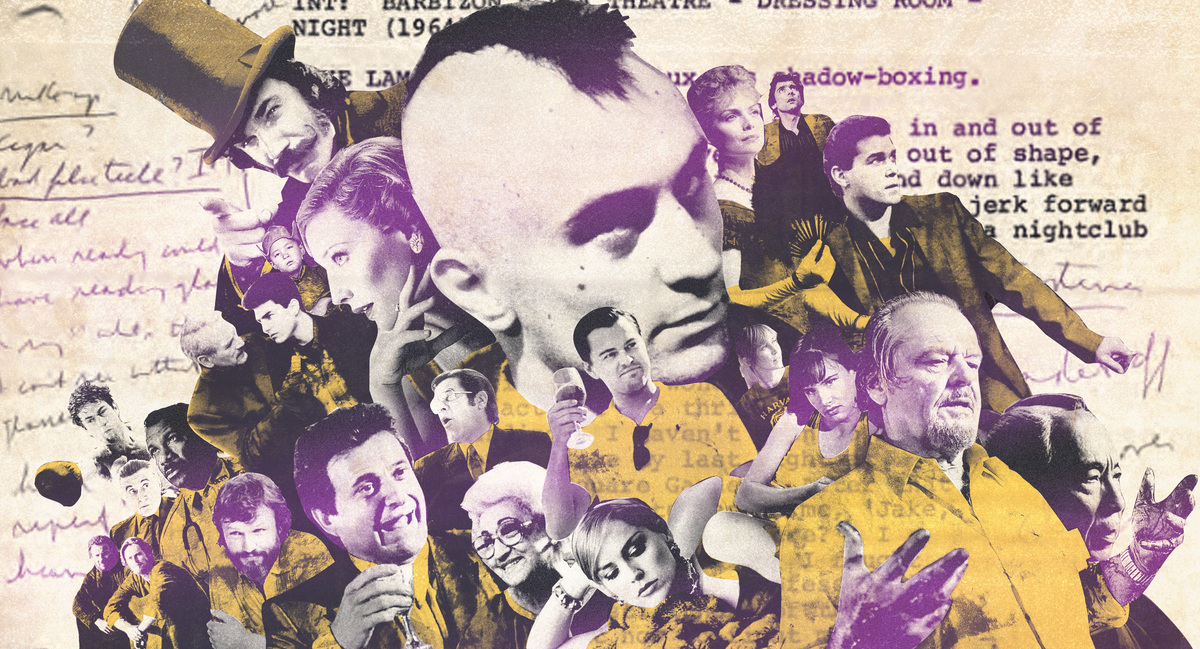

Soon, Grann’s stories will meet their most vast audience yet. This weekend, the Cannes Film Festival will premiere Killers of the Flower Moon, an adaptation of his 2017 book about a string of mysterious murders of Native Americans in Osage County, Oklahoma. The highly anticipated project is due out in theaters this October, and comes with an estimated $200 million budget, Leonardo DiCaprio as its lead, and none other than Martin Scorsese as its director. And—as if this crossover event featuring three men who are legends in their respective fields weren’t already enough to make cinephiles and bookworms lose it—Scorsese and DiCaprio have signed on to do it all again for The Wager, too.

The two films will cement Grann among the likes of Jessica Pressler and Michael Lewis—journalists whose stories resonate so deeply with society that they become part of pop culture. It’s a feat made all the more impressive by the fact that Grann’s stories are often sourced not from financial crises or flashy scammers, but from old documents that occasionally require a magnifying glass to read. His work may offer momentary escape in the form of far-flung locales, or the occasional naval cannon battle, but at its core are timeless themes of striving, survival, and the precarity of truth. In an era when so many film and television adaptations simply mimic our modern reality, Grann’s stealthy history lessons have become a powerful, if increasingly rare, force for scale and meaning in Hollywood.

“When people talk about content today … it all feels kind of indistinct,” said James Gray, who adapted Grann’s book The Lost City of Z into a 2016 film starring Robert Pattinson, Sienna Miller, and Tom Holland. “You have like 800 choices, but it feels like there’s nothing. The reason for that is corporate ideas have been to reduce the idea of ambition and quest and myth. These shows feel like the vision of reaching is crimped somehow. David’s work is very much the opposite of that.”

Practically every Grann fan can recall the first time they came across his work. For me, it was my senior year of college. I’d picked up an issue of The New Yorker before my shift at the campus library and began reading what I initially thought was a story about the politics of art authentication. It unfolded like an elegant piece of origami, describing what some say was an elaborate con in which a man allegedly forged the fingerprints of famous painters on so-called newly discovered works of art. When I finished the story, I looked up from the magazine to realize I was 20 minutes late to work. It was years later, when I landed a job at Condé Nast and overheard editors in the elevator discussing Grann’s writing as if it were sport, that I realized I was not alone in my awe of his work.

For Edward Zwick, a longtime writer, director, and producer, the first Grann story that really stuck with him was “To Die For,” a 2001 piece in The New Republic about 1930s celebrity and murder. Zwick clipped it out of the magazine with the thought that it could one day become a movie.

“It was just a really great story,” said Zwick, who has worked on dozens of film and television projects and won an Academy Award in 1998 as a producer on Shakespeare in Love. “I think it revealed even then what has been revealed in so many articles and stories since. That he has this uncanny ability to pull the threads of these strong narratives out of these stories.”

Zwick continued to follow Grann’s career, and finally got the chance to bring his work to the big screen when he directed Trial by Fire. The 2018 drama stars Laura Dern and is based on an article about the sketchy police evidence used to sentence a man to death for the murder of his three daughters in a house fire. Zwick recalls the ease with which the piece’s deeply researched “narrative thrust” both laid out the structure of the film and allowed him to preserve its core truth. “You’re allowed to compress and to be reductive in certain things and to combine characters,” he said. “But there has to be something in the essence of a story that gives you that kind of narrative shape that is familiar and yet unique unto itself.”

Geoffrey Fletcher, who adapted the script, said that Grann’s concise writing makes it a natural fit for film.

“David’s stories are richly and efficiently told in a way that is very cinematic,” Fletcher wrote in an email. “To me, his work and style are reminiscent of Hemingway’s.”

Trial by Fire was one of two movies inspired by Grann’s work that came out in 2018. On the very same day and at the same venue as Zwick’s premiere—that is, August 31 at the Telluride Film Festival—David Lowery debuted The Old Man & the Gun. (In that movie, Robert Redford plays a suave septuagenarian stickup-man-slash-escape-artist who was the subject of Grann’s 2003 article of the same name.) From that moment, Grann was on the map as a narrative powerhouse in Hollywood. Per Gray, his work is now especially sought after by directors who are drawn to ambitious historical dramas.

“A lot of us are old enough to remember not just the endeavors of Francis Coppola in the late 1970s, but also David Lean in the ’60s, and what that meant for reigniting a passion for cinema after the advent of television,” Gray said. “David’s stories conjure that aspect or that corner of the movies. They do generate a level of excitement, certainly as potential pictures.”

When Gray signed on to adapt The Lost City of Z, he was moved by the wit in Grann’s writing and the tenderness he displayed toward his characters. The director said that, in particular, Grann’s journalistic rigor elevated the adaptation.

“I was absolutely thrilled by David’s terror that I would take a risk with the facts,” Gray said. “I loved how important it was that his research never be questioned for its accuracy. And so that is a beautiful thing that spreads throughout the production. You say: I owe it to, not just to the material, but to Grann because of how dedicated he is to being specific and honest, truthful.”

Even so, Grann understands that for his stories to flourish on-screen, he has to let go of them.

“Adaptations are always scary, because there’s this part of you that wants to make it your own, but then there’s also this part of you that feels guilty for making it your own,” said Soo Hugh, who is making an Apple+ series based on Grann’s book about the Antarctic explorer Henry Worsley. “From the very first conversation, [Grann] said, ‘I know what this will take, this is no longer mine. I give it to you.’ Which is a very generous thing to do.”

For all the excitement Grann’s stories generate in Hollywood, he says he doesn’t “pretend to be a movie person” and has only so much influence.

“You know how, on a ship, you got the captain, then you got the lieutenant, and then you’ll have the petty officers, and then you’ll have the able seamen, and then you have the ordinary seamen, and then there’ll be a few landlubbers who are the most pitiful, pathetic creatures on board and are looked down upon?” Grann said. “In the hierarchy of the regiment with a film, the author is somewhere down there.”

He’s nevertheless been invited to observe the process, journeying to Cincinnati, Ohio, for the filming of The Old Man & the Gun, into the Colombian jungle for The Lost City of Z, and—most recently—to Oklahoma for Scorsese’s adaptation of Killers of the Flower Moon. For him, the most exciting part of these visits is not his proximity to movie stars or famed directors, but the opportunity to see his research materialize in real life.

Grann is especially grateful for the level of detail and respect brought to the production of Killers of the Flower Moon. He says Scorsese’s team began communicating early with the Osage chief Standing Bear, who appointed Osage ambassadors for various aspects of the film. Their collaboration ensured the Osage had a part in telling the story, influencing costume design, casting, language coaching, and their decision to film on location.

“I will say the one thing about working with Martin Scorsese and his production team and the actors in this project,” Grann said. “One of the most gratifying things to me was just their intense—I don’t want to say ferocious—but just intense commitment to dig into the story.”

Last year, when Grann visited the set, he found himself walking down a road he’d spent so many years researching so that he could offer the best possible descriptions in his book.

“I had seen these places and photographs and had descriptions of them, but they reconstructed everything into the finest details,” he said. “The walk down the street with all the little towns and thousands of people, buggies going up and down the street, they had very fancy cars at the time …”

For a moment on our call, Grann trailed off into a tangent explaining the Osage’s wealthy 1920s lifestyle on their oil-rich territory; he was lost in the vast historical detail that his mind held on the subject. Then he returned to his childlike awe of that moment on set.

“It was just totally surreal,” he said. “And surreal is not a word I normally use because what does surreal really mean? But in this case, surreal would be the way I felt.”

It’s only a matter of time until the vessel he spent so many years researching appears before his eyes, too.