Any discussion about the current state of NFL strategy should begin with the 2018 season. That was the start of the Patrick Mahomes era in Kansas City. It was also the year Sean McVay firmly established himself as one of the NFL’s elite head coaches. The Chiefs and Rams’ record-setting Monday Night Football battle that year, a 54-51 win for Los Angeles, looked like a Don Coryell fever dream. More passing plays went for at least 10 yards (34) than there were run plays called (32). And in a league that was becoming increasingly pass happy, the matchup felt like a glimpse into a future in which the run game and defense—long thought of as the pillars of championship football—were an afterthought.

Even then, though, the idea that the Chiefs and Rams had broken defensive football forever did not last very long. Then–Bears defensive coordinator Vic Fangio laid out the blueprint for stopping McVay’s offense during the Rams’ late-season loss in Chicago. Bill Belichick would later use a similar plan, with a few key tweaks, to hold the Rams to three points in the Super Bowl. And two weeks before that masterpiece, Belichick took down Kansas City in the AFC title game with a finely crafted game plan. The following season, teams across the league adopted the defensive tactics New England used in those two games.

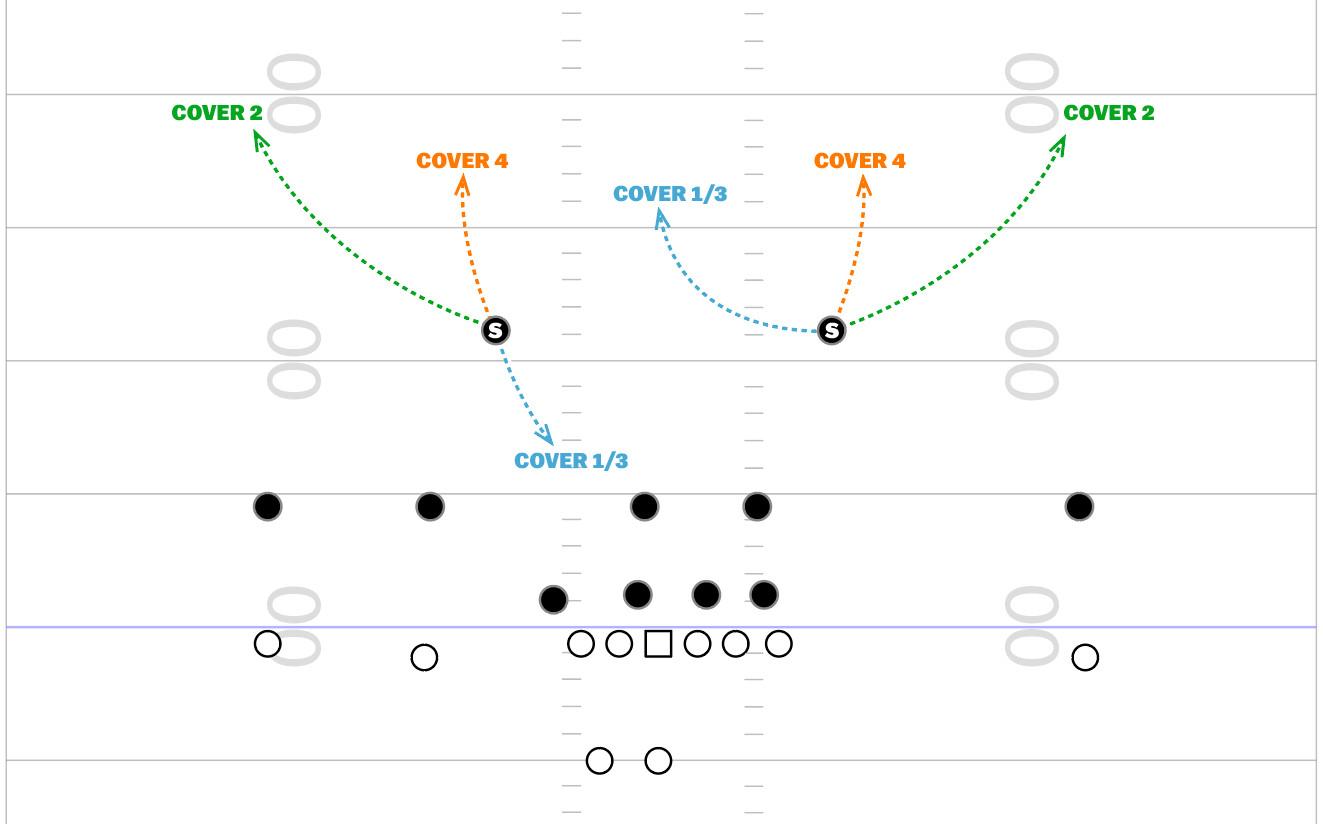

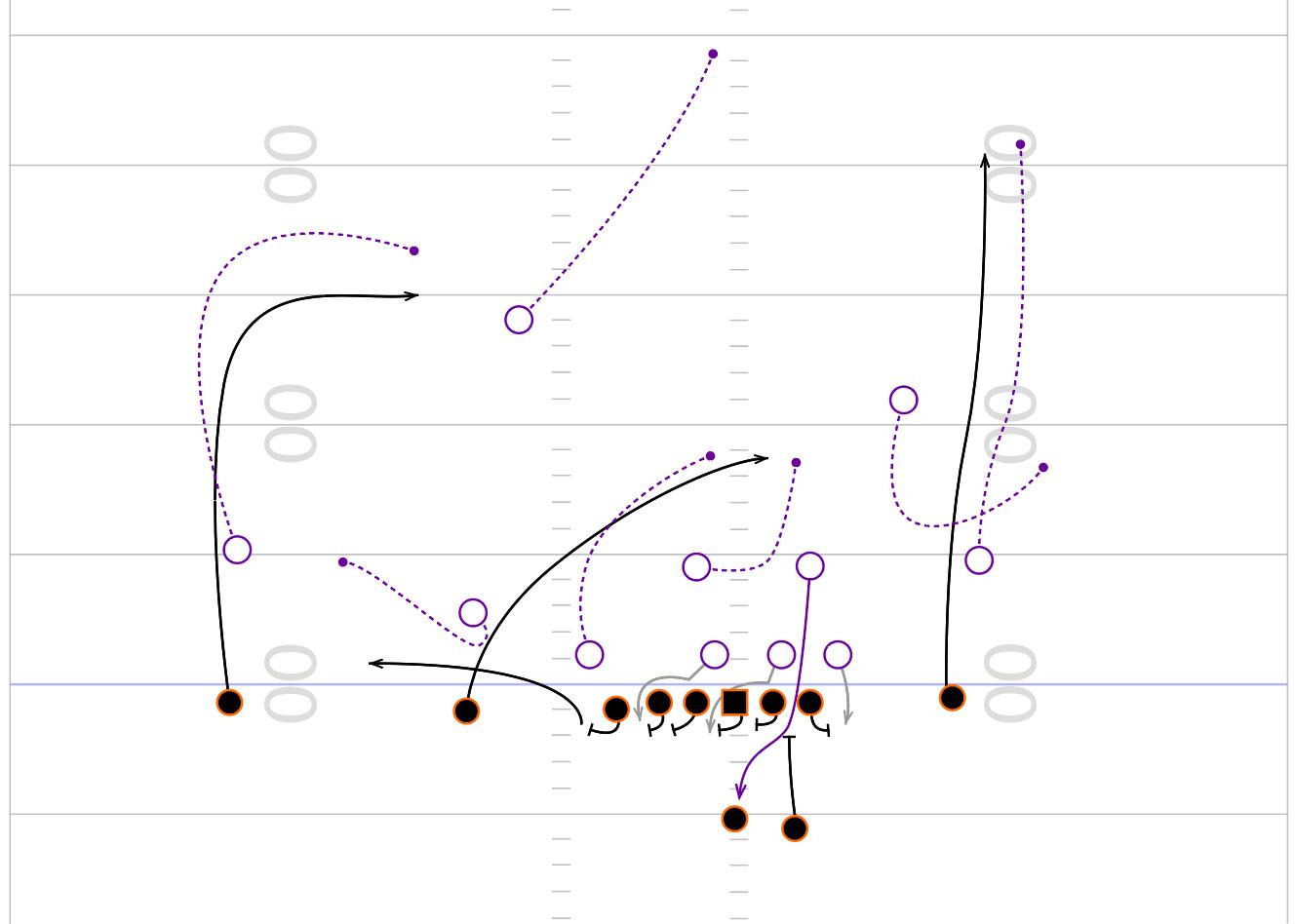

That was the genesis of the two-high trend in the NFL: With two safeties back deep, defenses were in a better position to defend the deep parts of the field—which came in handy against Mahomes—while also allowing for more disguises, which helped against McVay’s play-action-heavy attack. The two-deep structure allows defenses to get to all of today’s popular coverages from the same pre-snap look:

Defenses spent the next few years devising even more strategies to stop these high-powered passing attacks—not just the ones in Los Angeles and Kansas City, but also those in Buffalo, San Francisco, and eventually Cincinnati. And, based on the league-wide passing numbers, these new defensive strategies have been fairly effective. In 2022, NFL quarterbacks averaged 0.01 expected points added per dropback, per TruMedia. That number was at 0.08 in 2018. And the league-wide pass rate dropped to 60.1 percent last season, the lowest it’s been since 2011.

But to better defend the pass, defenses have had to sacrifice in the run game. Keeping a second safety back deep means one less defender in the run box. As you might expect, run plays have become more efficient.

NFL Pass Rates and Efficiency Since 2018 (via TruMedia)

You might look at this trend and think we’re headed for a return to old smashmouth football, but I’d caution against that. Passing efficiency has dipped several times in the last three decades, and it always bounces back when offensive coordinators find counters to the prevailing defensive strategies of the time. It’s an ongoing war of strategy that goes cold in February and picks back up every fall. It will start up again when the 2023 season kicks off in September. So to get a sense of what’s in store for the next phase of the NFL’s scheme wars, we’ll look back at five games from the 2022 season.

Week 1: Buffalo Bills 31, Los Angeles Rams 10

A new Josh Allen emerges and picks apart the defending champs.

Josh Allen was one of the quarterbacks most affected by the rising popularity of two-high coverages during the 2021 season. While he played like a superstar during the entire campaign, racking up more than 4,400 passing yards and throwing 36 touchdowns, his efficiency numbers took a big hit and he threw a career-high 15 interceptions. With defenses fixated on limiting his downfield opportunities, he clearly needed to develop a more well-rounded short game in 2022.

Playing the defending champion Rams on opening night gave Allen an immediate opportunity to show his improvement. The Rams had helped spark the two-high craze in 2020 when Brandon Staley was their defensive coordinator, and a season later, they won a Super Bowl by wielding the same defensive tactics. You didn’t have to sit in on team meetings to figure out how L.A. would try to defend Buffalo in last year’s opener: They were going to drop into conservative zone coverages and force Allen to attack underneath. The Rams wouldn’t let Stefon Diggs and Gabe Davis beat them deep, even if it meant giving up short completions. Eventually, that dog in Allen would come out, and he’d force a throw downfield or take a bad sack trying to extend a play. It was just in his nature.

Except … that never really happened. Bills offensive coordinator Ken Dorsey called a bunch of quick passes that stretched the Rams underneath, and Allen took what the defense gave him.

He finished the game with a perfect on-target throw rate and the third-lowest time to throw of his career. He picked apart L.A.’s defense like Tom Brady would have—only if Brady could do this when a defense won in coverage:

With Allen leading the offense up and down the field—Buffalo didn’t punt the entire game—L.A. defensive coordinator Raheem Morris was eventually forced to call riskier coverages. That was when the floodgates opened:

Even while Allen was playing with more restraint, he still managed to pull off some superhuman shit:

With Allen operating on this level, Dorsey could dial up a little bit of everything—quick game, deep dropbacks, under-center runs, designed QB keepers, run-pass options—and his supernatural quarterback was at the heart of it all.

The Bills came into the season as Super Bowl favorites, and Allen was one of the favorites to win MVP. Expectations were high for the fifth-year QB, but even by his lofty standards, this was an eye-opening performance. Allen looked like the best player in football and did so against a defense that was designed to stop quarterbacks like him. How do you stop Superman when even the kryptonite isn’t working?

An elbow injury, apparently. Allen partially tore his UCL midseason, which threw off his short-area accuracy. With Allen unable to hit the layups consistently, the Bills’ passing game reverted to the boom-or-bust approach it had during the early stages of Allen’s development. Things unraveled from there.

What it means for 2023: Before Buffalo’s season slowly fell apart, Allen and the Bills showed us how the top offenses could fight back against the scourge of two-high coverage. They have to be able to do more things early in a series, whether it’s running the football more effectively, using quick passes to ensure positive gains, or turning to more QB-option concepts to punish defenses that try to cheat with fewer numbers in the box. McVay chalked up the success of his early Rams offenses to the “illusion of complexity.” Against today’s defenses, illusion isn’t nearly enough.

Week 3: Denver Broncos 11, San Francisco 49ers 10

Denver’s defense sends Kyle Shanahan looking for answers.

Shanahan tried his darndest to land a quarterback with Allen’s potential, giving up three first-round picks and a third-rounder in the hopes that Trey Lance could eventually develop into that kind of player. And the North Dakota State prospect certainly fit the profile: He’s a big, strong athlete with a ludicrously powerful arm. Shanahan had gotten to two NFC championship games and a Super Bowl with the more stationary Jimmy Garoppolo, but having a mobile QB who could stretch the field vertically would take the offense to another level. That was the theory at least.

We still don’t know what Shanahan’s offense would look like with Lance under center. The 23-year-old broke his ankle in his second start last season, and the transformation of Shanahan’s offense had to be put on pause, as Garoppolo was awkwardly welcomed back into the starting lineup before this Sunday Night Football game in Denver.

While this was certainly a setback for Lance’s development, it wasn’t season-ending news for the Niners roster, which was built to win immediately. Lance may have offered a brighter future for the team, but he was a raw passer who would surely go through some growing pains. With Garoppolo, the offense had a much higher floor.

Garoppolo’s first start of 2022 came against the Broncos defense, led by first-year defensive coordinator Ejiro Evero, who had spent the past few seasons as an assistant with the Rams. He installed a scheme like the Rams’ in Denver—one that bases out of two-high looks even on early downs when run plays are more common and is particularly effective against the type of play-action-heavy attack that San Francisco runs. Defensive linemen are charged with occupying blockers rather than trying to get past them into the backfield, so linebackers and safeties have a little more time to diagnose the play call, allowing them to stay patient against the run and hang back in throwing windows. Shanahan’s offense is notorious for putting stress on linebackers, but Evero’s scheme offered them some protection against the man in the flat-brimmed hat.

There was no need to over-pursue ballcarriers when the 49ers went to the perimeter, which left Denver’s linebackers free to fill in cutback lanes:

All that perimeter work opens up large throwing windows for Deebo Samuel, Brandon Aiyuk, and George Kittle. Hit one of those dudes in the open field, and good things tend to happen. That’s how the 49ers typically managed to create explosive plays in the passing game despite Garoppolo’s aversion to throwing downfield. But the Broncos clogged up those windows and challenged Garoppolo to find a plan B.

Finding a plan B isn’t really Garoppolo’s thing. He’s at his best when he doesn’t have to think. He can just take the snap and fire the ball over the middle of the field. Against Denver (a team mired in its own offensive issues), those opportunities never came, and the 49ers managed just 10 points in one of the ugliest games of the Shanahan era. At one point during the loss, Garoppolo even appeared to criticize the play-calling.

When asked about the moment later, Garoppolo didn’t deny saying that Shanahan’s plays sucked. And he wasn’t wrong. Shanahan needed to find better answers when defenses took away his wide-zone runs and play-action keepers. So a few weeks later, the 49ers traded multiple draft picks for Christian McCaffrey. The move was initially criticized: It reeked of desperation after a slow start to the season. But Shanahan and GM John Lynch’s belief that the dynamic back would “unlock” the offense was ultimately justified.

After McCaffrey entered the starting lineup in Week 8, San Francisco didn’t lose another regular-season game—even with rookie Brock Purdy under center. The 49ers offense ranked 18th in EPA per play and 21st in success rate from Weeks 1 to 6, per RBSDM.com. After the McCaffrey trade, they ranked second and fourth in those metrics, respectively. McCaffrey improved the Niners’ run game, obviously, but it was his contributions in the passing game that allowed Shanahan to find success again.

San Francisco dialed back on its play-action usage after adding McCaffrey. Those plays were replaced by straight dropbacks that had him running option routes underneath and were typically paired with a deeper route breaking over the middle of the field. If defenses sold out to stop McCaffrey underneath, the deeper route would come open.

It was another way for the 49ers to access the middle of the field without relying on play-action, which can be a situation-dependent call. The running back was still the bait, but the presentation was far different.

What it means for 2023: In 2021, we saw McVay abandon some of the under-center concepts that had served him so well during his ascension, and now we have Shanahan doing the same. As those two innovators continue to tweak their schemes, the league’s infatuation with the wide-zone offense seems to be fading. For the first time in years, we didn’t see an offensive assistant from the McVay-Shanahan coaching tree land a head job during the 2023 offseason.

Week 14: Los Angeles Chargers 23, Miami Dolphins 17

Brandon Staley’s complex plan slows down Tua Tagovailoa’s Dolphins.

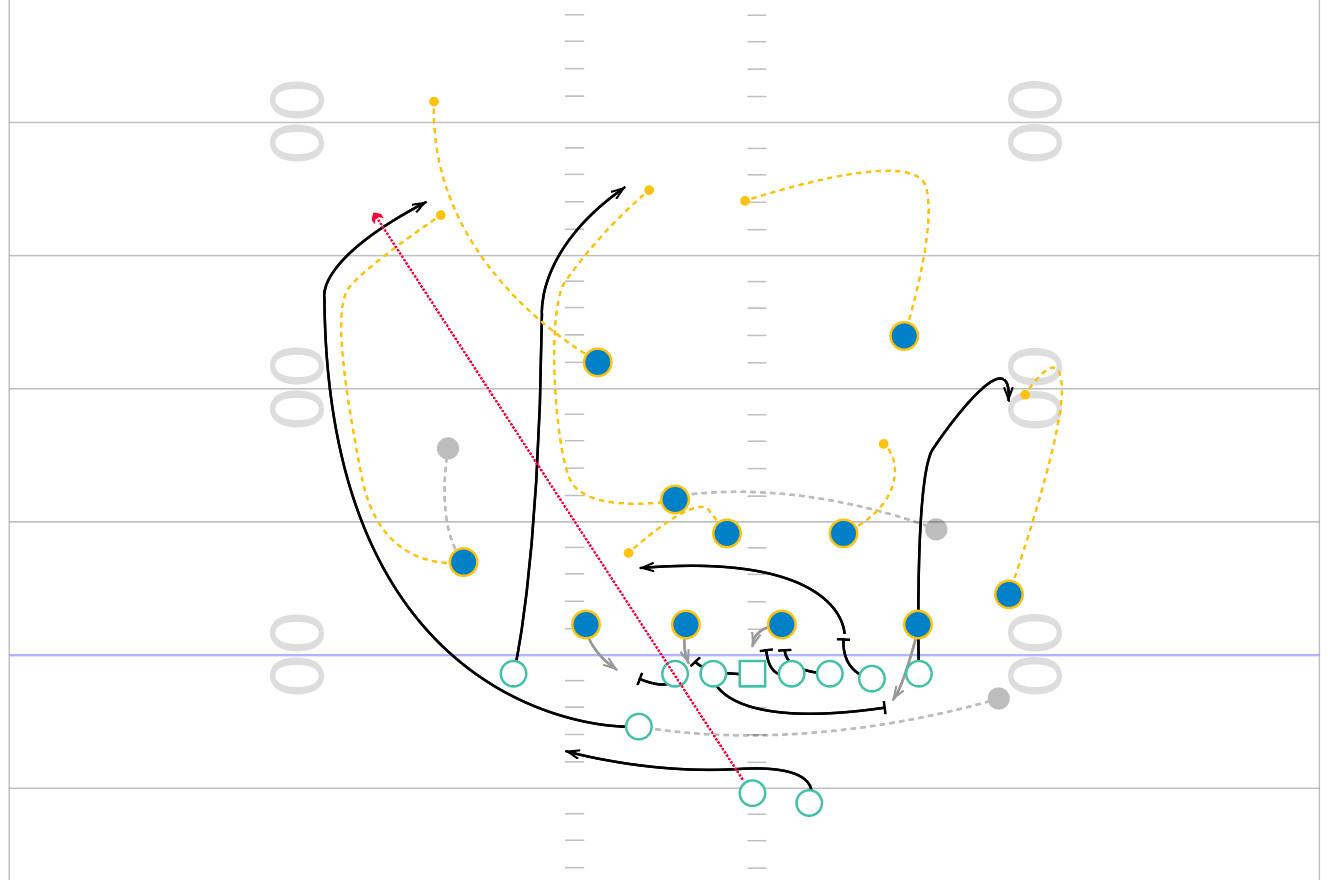

While his old boss was making changes in San Francisco, Miami’s first-year head coach, Mike McDaniel, was fielding his own version of a reimagined Shanahan offense. Instead of dialing back on play-action like Shanahan, though, McDaniel used even more of it. And it looked far different from the play-action fakes his old team ran in San Francisco. The Dolphins mostly operated out of the shotgun last season, to suit Tua Tagovailoa’s skill set. And instead of trying to stretch the defense horizontally, Miami’s play fakes were designed to freeze second-level defenders just long enough for Tagovailoa to send quick passes buzzing by their ears. Tagovailoa’s quick release, paired with Tyreek Hill’s and Jaylen Waddle’s ability to get downfield in a hurry, made it nearly impossible for defenders to make a play on the ball.

McDaniel wore that particular play design out last year. He called it 28 times on first down alone, and the Dolphins averaged 8.6 yards per play, according to The 2022 Miami Dolphins Complete Offensive Manual. That’s not a bad way to get a series going.

Miami’s speed is what makes the play difficult to defend. Waddle and Hill are usually the two receivers running the vertical routes, with one working up the seam and the other running a “rail” after motioning across the formation. Not only is one receiver getting a running head start at the snap, but the secondary is also forced to sort out their assignments on the fly. The play was especially effective when Miami’s stars were running it, but it even worked with the likes of Trent Sherfield.

Miami used that and similar concepts to protect their speedy receiving corps from contact at the line of scrimmage. McDaniel wanted Hill and Waddle hitting top speed as quickly as possible, and the switch releases ensured it would happen. Disrupting the timing of those routes was the clear solution for defenses, but they were understandably wary of playing press man coverage against the Dolphins’ all-world duo. And the two-high zone coverages that have become popular over the last few years weren’t very effective against Miami, either. Those defenses were designed to stop route combinations that attacked deeper areas of the field, and Tagovailoa got the ball out well before zone defenders could get to their proper landmarks.

For a time, it looked like the Dolphins would be impossible to defend. Miami scored at least 30 points in four straight games to close out November. Tagovailoa led the league in EPA and had established himself as a legit MVP candidate. McDaniel looked like a shoo-in for Coach of the Year. Even a 33-17 loss to San Francisco in December did little to derail the Dolphins hype because the 49ers defense was loaded with talent and Tagovailoa uncharacteristically missed several throws. The loss initially seemed more like a speed bump on Miami’s road to the playoffs than a real obstacle.

It turned out to be much more than that. The following week, a banged-up Chargers defense gave Miami even more issues than the Niners had. Staley’s unit hadn’t played well up until that point in the season, and it didn’t have Derwin James or Joey Bosa. But somehow, Los Angeles held the Dolphins offense to just two touchdowns, which included a bizarre scoop-and-score by Hill after a fumble on a short-run play.

Say what you want about Staley’s credentials as a head coach, but he can put together a defensive game plan. And this was his masterpiece. Staley had an answer for seemingly every play McDaniel called, including the one we outlined above, which the vaunted 49ers defense had its issues with. The Chargers saw it three times, though, and didn’t surrender a single yard. Staley did what few other coaches were willing to do against Hill and Waddle: He pressed them, instructing his team to knock all the Dolphins’ pass catchers off their routes. And L.A.’s defenders were well prepared to recognize when the play was coming. Watch the Chargers’ pre-snap communication after Miami got into its formation:

The goal was to mess with Tagovailoa’s timing. Miami’s quarterback is known for his quick decision-making, but he is prone to panic when the defense changes its look. “You have to start with the premise of making that guy work after the snap,” Staley told me last August. “Because pre-snap, those guys are so intuitive—they have such an inventory of experiences to draw from—what you’ve got to do is try and challenge them after the snap and just try to slow them down a count. Buy some time for your operation to work. And you have to do it over and over again.”

The key to a good defensive disguise is using that “inventory of experiences” against the quarterback. Show him a look that lulls him into a false sense of security, only to pull the rug out from under him. Fooling the best quarterbacks—or the ones with the best coaches—requires good design and a deep bag of tricks. And in that Week 14 game, Staley was a step ahead of Tagovailoa all night. The QB completed only 35.7 percent of his passes and averaged just 5.2 yards per attempt.

Back-to-back stinkers derailed the Tua for MVP campaign, and the Dolphins fell into a five-game skid that nearly tanked their season. The 49ers had beaten the Dolphins by overwhelming Tagovailoa with a ferocious pass rush that very few teams other than San Francisco could replicate. The Chargers did it by overwhelming him mentally. Those games showed the rest of the league that you really didn’t have to beat Miami’s two superstar receivers; you just had to beat the quarterback. When that guy isn’t a superstar who can adjust on the fly, it’s a far more manageable task.

What it means for 2023: In attempting to contain explosive passing games, NFL defenses had become a bit passive. It was an effective strategy for a time, but the top offenses and quarterbacks adapted, forcing defenses to do the same. Now, rather than conceding ground in hopes that the offense will make a mistake, the best defenses attack what the offense does best to force that mistake.

AFC Wild Card: Cincinnati Bengals 24, Baltimore Ravens 17

Mike MacDonald’s creativity nearly leads Baltimore to a playoff upset.

In an era when the top QBs all seem to possess elite physical abilities, Joe Burrow is an anomaly. The Bengals signal-caller is easily one of the five best quarterbacks in the NFL, but he’s an average athlete—based on today’s standards, anyway—with a below-average arm. Still, Burrow’s accuracy, processing, and unmatched feel for the game set him apart: He’s football’s answer to that internet guy who can take a quick peek at a photo of a random location and instantly tell you where it is—only Burrow does it with defensive coverages.

Having the receiving trio of Ja’Marr Chase, Tee Higgins, and Tyler Boyd also helps. The Bengals not only have a sentient football-playing computer under center, but they also have three legitimate stars running routes for him. You can’t double-team all of them, and even if you manage to cover two, Burrow has no problem working through his progression to find the open man.

There have been times when Burrow has been a little too committed to the bit, though. He took a lot of sacks over his first two seasons, and many of them were because he held on to the ball too long. That not only exposed the franchise’s most valuable asset to more hits, but also derailed the offense at times. The Bengals made enough big plays to offset those negative ones and used that boom-or-bust formula to make the Super Bowl in the 2021 season, but Burrow knew that Cincinnati would be seeing more two-high defenses in 2022, which would require adjustments for both the offense and his playing style.

Burrow’s prediction came true. And after a few weeks of growing pains, he eventually became more willing to throw a checkdown. He targeted running backs nearly twice as often in 2022 as in 2021, and his sack rate was cut in half. The Bengals weren’t hitting on nearly as many downfield throws—but Burrow would figure that out, too.

As he got more reps against two-high coverages, Burrow realized that if he started the game peppering the underneath areas of the field, defenses would grow restless. It was as if Burrow were trying to bait them into coming out of the two-high shell and being more aggressive. This was the same type of QB maturation we had seen Mahomes and Allen go through from 2021 to 2022, and here was Burrow speedrunning that process in a matter of weeks.

As good as Burrow and the Bengals’ passing attack was in 2022, though, they didn’t fare so well in the three games against the Ravens and first-year defensive coordinator Mike MacDonald. Cincinnati won two of those games, including the wild-card game in January, but the defense did most of the heavy lifting as Burrow averaged 5.0 yards and minus-0.11 EPA per dropback across the three matchups.

The Ravens Defended Burrow Well in 2022 (via TruMedia)

MacDonald has just one year of NFL play-calling experience under his belt, but he’s already established himself as one of the best at disrupting a quarterback’s thought process. Doing so against a panicky passer like Tagovailoa, as Staley had done in Week 14, is one thing; doing it against an unflappable quarterback like Burrow requires real ingenuity and a well-drilled unit.

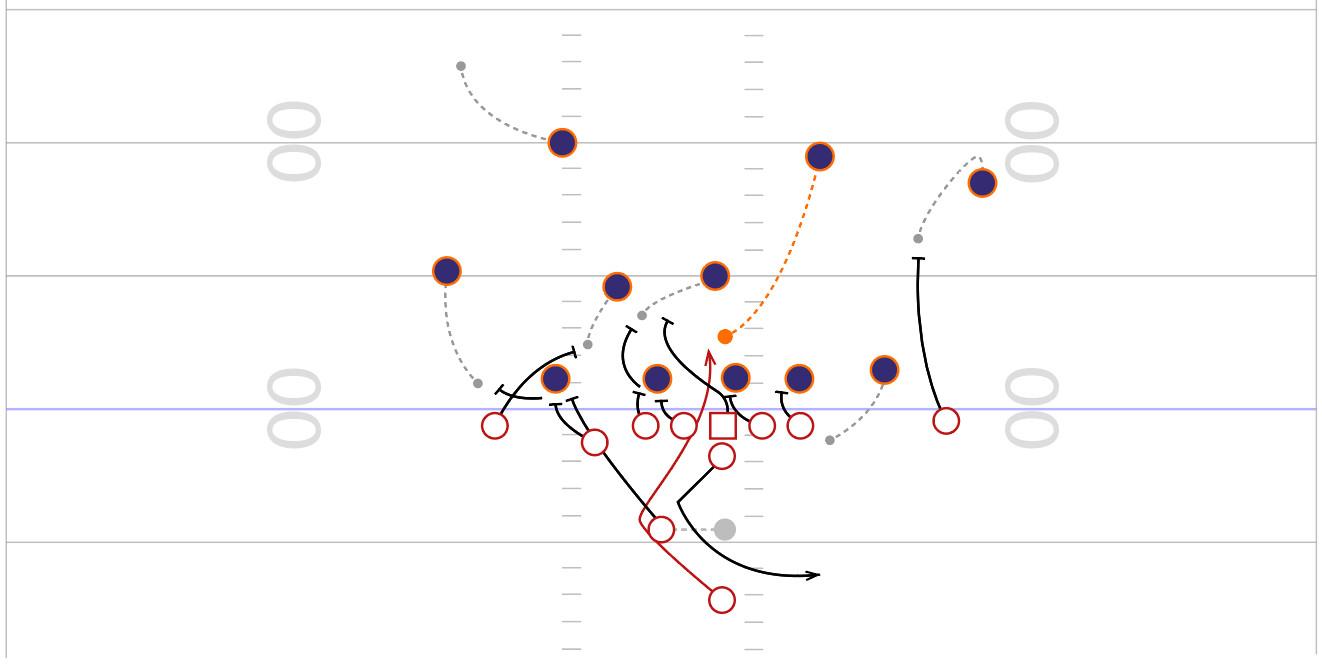

The Ravens ultimately lost to Cincinnati in the wild-card round, but MacDonald’s defense did its job, holding the Bengals offense to two touchdowns. MacDonald used simulated pressures—a four-man rush that looks like a blitz because a second-level defender rushes the quarterback, but a more traditional pass rusher, like a defensive end, replaces that player in coverage.

Simulated pressures make it difficult to figure out which players are rushing and which are dropping back, so offenses will typically just keep the running back in as an extra blocker. That was certainly Cincinnati’s answer. But Burrow had been throwing to his backs when defenses took away his deep options. And with them helping out in protection against Baltimore, Burrow was often forced to take a sack or just throw the ball away.

Anytime you can make a quarterback reconsider his option after the snap, it’s a win for the defense. And MacDonald has a deep bag of schematic tricks.

What it means for 2023: Simulated pressures are a safe solution for defensive coordinators who want to speed up a quarterback’s thought process without blitzing and leaving the secondary vulnerable. The best coordinators have been getting good mileage out of them for a while now, but they’re starting to become a common tool as more diverse offenses necessitate more creative calls from the defense. Look for NFL defenses to lean on simulated pressures even more in 2023 after seeing how effective they’ve been against the league’s best passing games.

Super Bowl: Kansas City Chiefs 38, Philadelphia Eagles 35

Nothing could stop this new-age QB duel—not even a dominant defense or a brilliant game plan.

NFL offenses may have regressed statistically in 2022, but you wouldn’t know it from watching the Super Bowl. The Chiefs and Eagles combined for 73 points in a thrilling duel between Mahomes and Jalen Hurts.

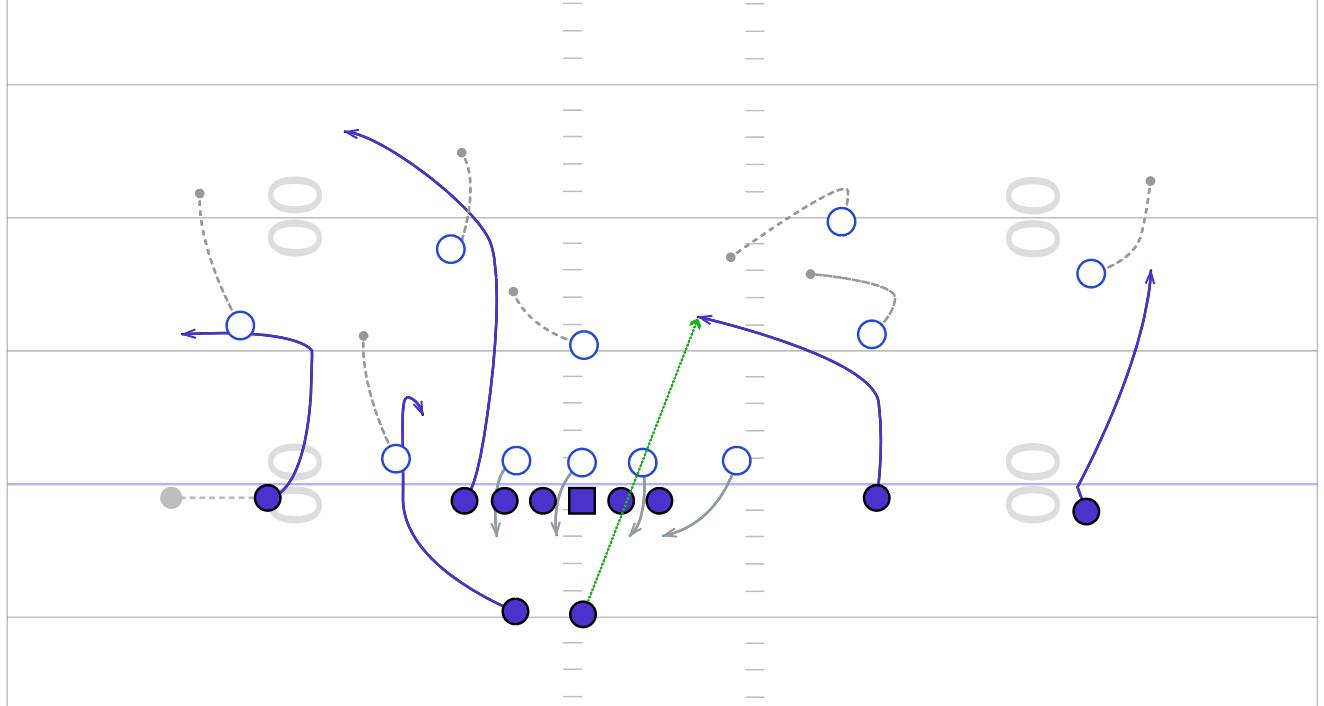

That Mahomes played well, even against an elite defense, was hardly a surprise. As good as Philly’s defense had been throughout the season, it wasn’t terribly complex. It had an unblockable pass rush that led the league in sacks, so then–defensive coordinator Jonathan Gannon didn’t need to do anything fancy in coverage to get his team to the Super Bowl. Against Kansas City, Gannon used a lot of the two-high coverages that had given Mahomes fits in the past, but he didn’t go out of his way to disguise them. And after a slow start to the championship game, Mahomes and Andy Reid figured out Philadelphia’s scheme and bent it to their will.

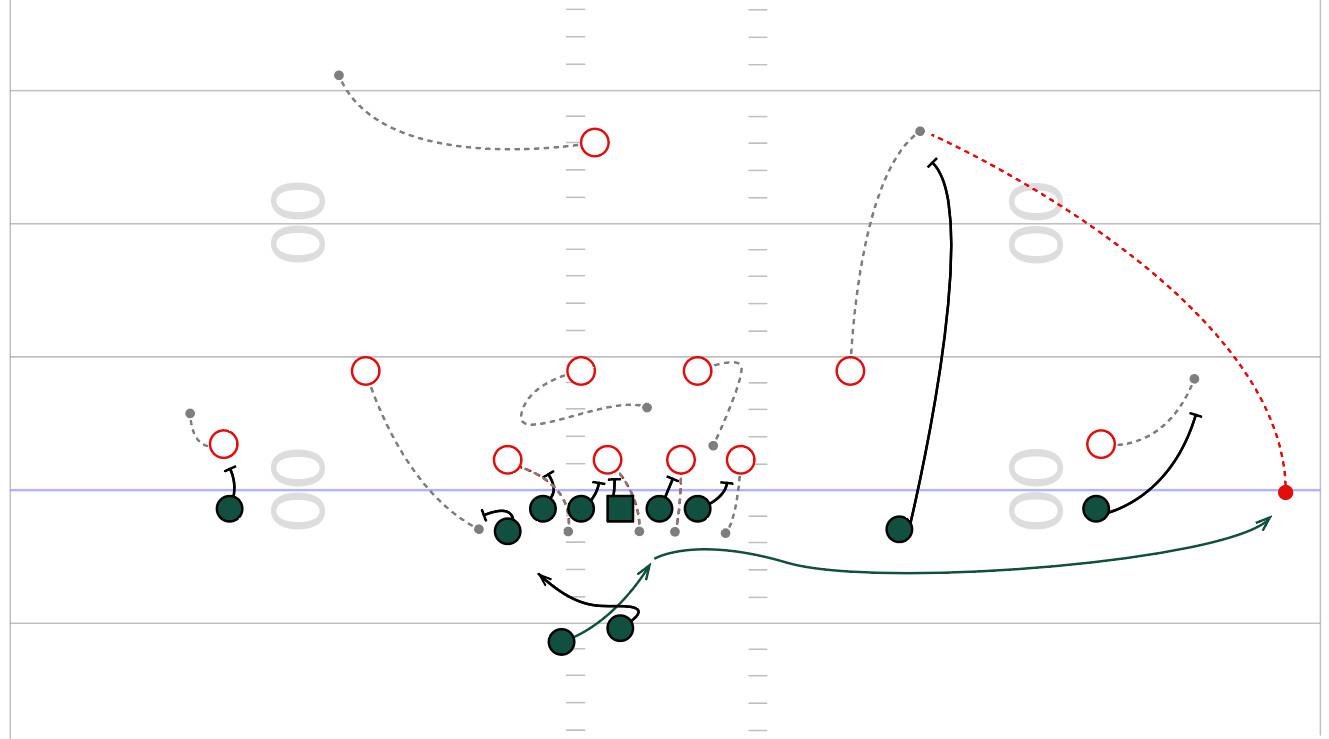

That the Eagles even had a chance of keeping pace with the NFL MVP is a testament to Hurts’s value and Philly’s loaded roster. Kansas City defensive coordinator Steve Spagnuolo had put together an awesome plan to limit Philadelphia’s QB-powered run scheme while still not leaving his corners on an island against A.J. Brown and DeVonta Smith. He did it by using the techniques Macdonald and Staley had used against Cincinnati and Miami—only instead of using pre-snap disguises to disrupt the passing game, Spagnuolo used them against the run.

Before the snap, the Chiefs would show the Eagles a front that might be vulnerable to a certain Philly run concept. But that was just bait. As soon as Hurts signaled to the center that he was ready for the snap, Kansas City rotated to a different look, pinching the line to take away the Eagles’ inside run. Here, Miles Sanders bounced outside, which gave the Chiefs secondary time to rally for a tackle behind the line of scrimmage.

The plan kind of worked, as Philadelphia’s running backs combined for just 45 yards on 17 carries. But unfortunately for Spagnuolo, Hurts was so good that it didn’t matter. The young QB made a handful of perfect throws into tight coverage, and eventually Eagles offensive coordinator Shane Steichen stopped trying to feed his running backs altogether, using designed quarterback runs from spread formations to attack Kansas City.

Hurts’s role in Philadelphia’s success had been a hotly debated issue the entire season: Was he the main catalyst for it, or just the product of a stacked roster and smart coaching staff? In the biggest game of the season, he left little doubt: Hurts was no system QB—he was the system. His presence in the run game protected his star receivers from limiting coverages. His playmaking ability gave the Eagles a chance even when the defense managed to cover Brown and Smith. And his skill as a ballcarrier gave Steichen a “break in case of emergency” option whenever the offense fell into a rut.

What it means for 2023: On this night, we watched a hobbled Mahomes burn down Philly’s elite but hardly complex defense while Hurts’s dynamic skill set laid waste to a well-thought-out defensive plan. This new batch of elite quarterbacks can throw, they can run, and they’re getting pretty damn good at the mental aspects of the position. Offensive coordinators lucky enough to work with one of these dynamic talents are bound only by their own imaginations. With defenses getting better at defending more complex concepts, schematic flexibility will become a necessity for a successful offense rather than a luxury.

If defenses are going to keep pace, they’ll have to get more creative. Simply lining up in static two-high coverages isn’t as effective a solution as it may have been a year ago. Quarterbacks are already learning how to pick those defenses apart, and the dual-threat QBs don’t even need to put the ball in the air to do it. The 2022 season showed us that the only way to keep pace with the league’s increasingly creative offensive strategies is with equally creative defensive answers. This means more shrewdly designed coverage disguises, more simulated pressures, and even more game plans specifically tailored to stopping individual offenses. In that way, the NFL’s scheme war is becoming an arms race in which quantity is just as vital as quality.