Hossein Khosrow Ali Vaziri, best known to wrestling fans as the Iron Sheik, died this week at the age of 81. Born in 1942, the Iron Sheik wore many hats—and kaffiyeh—over the course of a career that stretched from the amateur mats in Iran in the 1960s to a monthlong run with the WWF Championship to a long phase of in-ring decline, a battle with drug addiction, and at last a long, happy coda that saw him become a social media influencer. It was there that the Iron Sheik arguably solidified his legacy: He was one of the first great superstars sparring in social media, now used heavily by the wrestling business.

The narrative of Iron Sheik’s early life is a simple one. Born in Iran as a Shiite Muslim, he grew up with a talent for amateur wrestling—an interest shared by many young boys in a country with an illustrious history in the sport. His fervor was fed by the legendary 87-kilogram gold medalist Gholamreza Takhti, a national hero who dominated on the mats in the 1950s and 1960s. The Sheik also wound up serving as a guard for Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Looking back, the irony is stark: The man who would later portray an Iranian fundamentalist—a fictional representative of the government that overthrew the shah—and an Iraqi sympathizer, Colonel Mustafa, once stood guard for the shah himself.

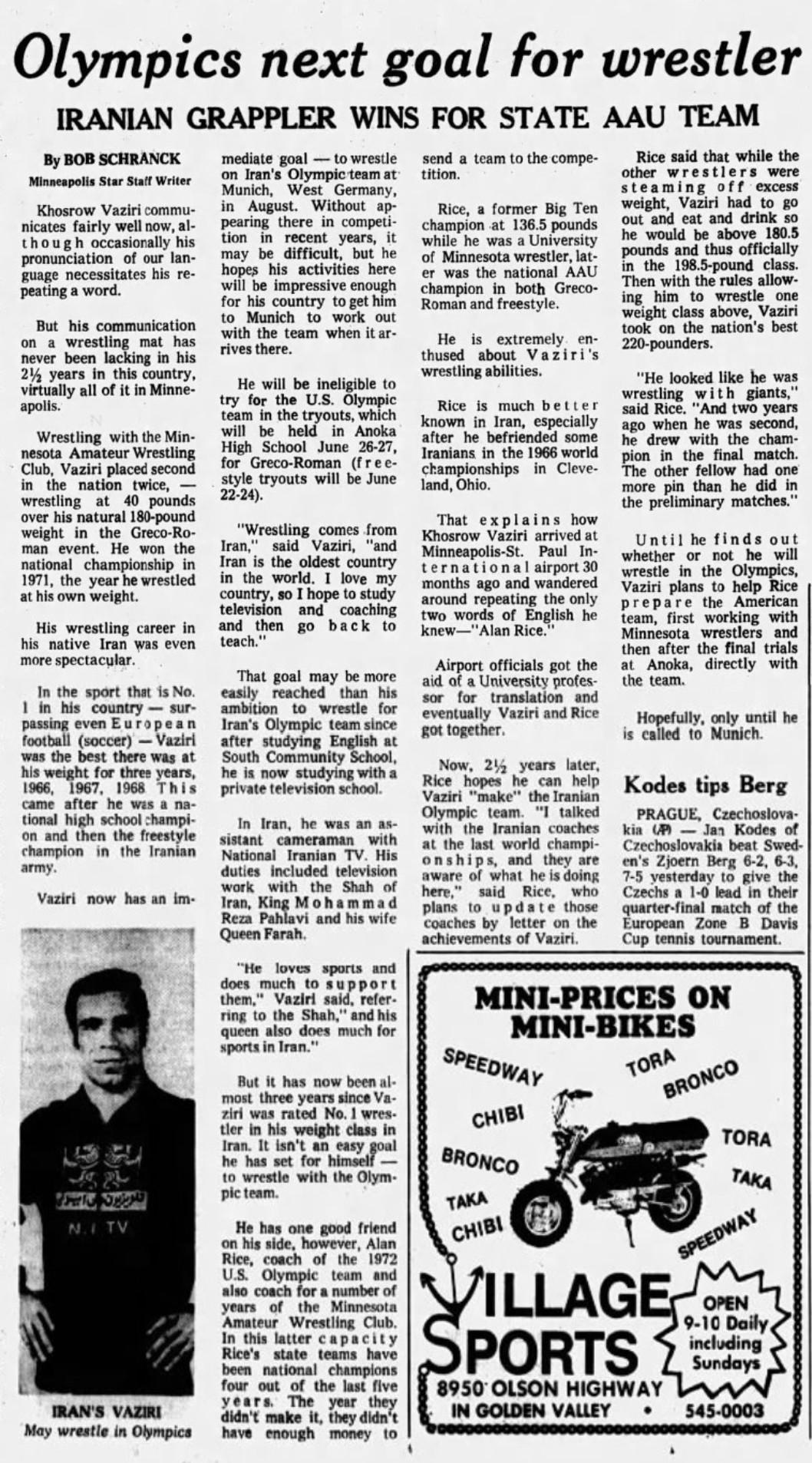

After the death of Takhti (itself shrouded in mystery), the Iron Sheik relocated to the United States in 1968, carrying with him just a modest understanding of the English language, limited, according to a 1972 Minneapolis Star article, to two words: “Alan Rice.” This was the name of the 136.5-pound national AAU champion in Greco-Roman and freestyle wrestling from the University of Minnesota who had bonded with the Sheik and other Iranian wrestlers at the 1966 world championships.

With determination and the same spirit that had propelled him in Iran, the Iron Sheik found his ground in American wrestling with the Minnesota Wrestling Club. In 1971, he won the 180.5-pound Greco-Roman AAU National Championships. In 1972, The Minneapolis Star reported an interesting side note about his work with the U.S. Olympic team. Ineligible for a spot on the U.S. roster, he still trained with the team and made the journey to Munich with the aspiration of being granted a spot to compete on the Iranian team. He was added to the Iranian Greco-Roman roster, but he was unable to compete in the games.

By 1974, the Iron Sheik was under the wing of American Wrestling Association promoter and former University of Minnesota collegiate champion Verne Gagne. Reflecting on those days, Greg Gagne, Verne’s son, recalled how the Iron Sheik was initially skeptical about pro wrestling. To prove that pro wrestlers were legitimate, Verne responded to this skepticism with a dropkick that connected squarely with the Sheik’s head.

Questioned by The Minneapolis Star in December 1974 about his transition to pro wrestling, the Iron Sheik responded with a simple yet profound statement, “I can’t eat gold medals.” His response to a query about the distinction between amateur and pro wrestling was a melancholic “It is different.” We can surmise that the Sheik had dreamed of emulating Takhti rather than becoming a wealthy dropkicking success like amateur turned pro Verne Gagne. The article also made a point of highlighting his abstinence from smoking and drinking, in line with his observation of the Muslim faith—something that certainly would change during the ensuing decades.

As he entered the world of professional wrestling, the Iron Sheik adopted a style reminiscent of Gagne’s: He was a fast-moving, lean amateur “babyface.” But this persona did not sit well with him. Over time, he incorporated Middle Eastern elements into his performance: wrestling boots with curled toes, a thick mustache, and a keffiyeh headpiece. It was Gagne’s wife, Mary, who reportedly came up with the name “the Iron Sheik,” a nod to Ed “the Original Sheik” Farhat (who, before the Iron Sheik’s emergence, was known simply as “the Sheik”). Boasting a badly scarred forehead from decades of self-inflicted wounds, the Original Sheik had been a main-event fixture since the 1950s. However, Farhat was neither as physically imposing nor as legitimate a grappler as the Iron Sheik.

When the Iron Sheik wrestled in territories and promotions where Farhat had worked extensively, he initially used alternative names. For several years, he wrestled under monikers like “the Great Hussein Arab,” “Hussein Arab,” and “Muhammad Farouk.” In 1979, for example, he wrestled as Hussein Arab during his first stint in the WWF in a series of title shots against fellow amateur wrestling standout and then–WWF champion Bob Backlund. The Iron Sheik would lose that title series but would dethrone Backlund four years later.

The Iron Sheik’s wrestling journey took him from WWF to Jim Crockett Promotions in 1980, and he won the Mid-Atlantic Heavyweight Championship from “Jumping” Jim Brunzell. (Interestingly, Brunzell would later team up in the WWF with B. Brian Blair, one of the Iron Sheik’s longtime adversaries, to form the Killer Bees.) In addition to this victory, the Iron Sheik also made a notable challenge for Dusty Rhodes’s NWA Worlds Heavyweight Championship in July 1981—his highest-profile bout to date.

The defining moment in the Iron Sheik’s career, the event that catapulted him into the limelight and forever etched his name in wrestling history, was his return to WWF in 1983. During stints in Florida and Georgia earlier that year, when he was still part of Jim Crockett Promotions, he continued to refine his Middle Eastern villain gimmick, setting the stage for his career transformation.

Brian Solomon’s recent work Blood and Fire: The Unbelievable Real-Life Story of Wrestling’s Original Sheik sheds light on the Iron Sheik’s rapid career trajectory. Solomon emphasizes how, in the eyes of young promoter Vince McMahon, the Iron Sheik was the ideal transitional villain to dethrone Backlund, the athletic amateur wrestler and longtime WWF champion. (Transitional champions like the Sheik allow babyface titleholders to lose their title without having to be defeated by another babyface.) This was reminiscent of the tactics McMahon’s father had previously used to transition titles, like when Ivan Koloff unseated Bruno Sammartino in 1971, opening the path for Pedro Morales’s reign.

The Iron Sheik’s legitimacy as a villain was reinforced by his Persian heritage. Unlike Farhat, who was born in the Midwest and was far removed from his Arabic roots, the Iron Sheik could capitalize on the surging Islamophobia that had followed the fall of the American-allied shah and the 1979 Iranian hostage crisis. He could inspire awe from the crowd by swinging heavy Persian clubs before each match and shouting in a mixture of English and Farsi.

After taking down Backlund, the then-41-year-old Iron Sheik turned his sights on emerging WWF superstar Hulk Hogan. Wrestling history presents an intriguing backdrop here, as both Hogan and the Sheik claim that Gagne, whose AWA had lost Hogan to the WWF, offered the Sheik money to break Hogan’s leg in the ring. Whether this is true has been hotly debated by pro wrestling fans ever since. Nevertheless, Hogan and the Sheik agreed that the offer was made and that the Sheik decided against it; whether the Iron Sheik could have executed it is another matter.

In any case, Hogan emerged victorious, and the Iron Sheik went on to showcase some of the best wrestling of his career in subsequent WWF fights. Critics like Dave Meltzer hailed his red-hot feud with Sgt. Slaughter, who would later become the face of the G.I. Joe action figure line. Their bloody 1984 “Boot Camp” match at Madison Square Garden is regarded as one of the best WWF bouts from the early 1980s—on par with Slaughter’s similarly brutal match with Pat Patterson.

The Iron Sheik had now cemented his notoriety thanks to appearances on a Saturday-morning cartoon, an action figure, and loads of national TV exposure. Following this breakthrough, the Iron Sheik was paired with Nikolai Volkoff, who portrayed a die-hard Soviet. Managed by “Classy” Freddie Blassie, they became an incendiary duo, wielding Iranian and Soviet flags and inciting the crowd with the Soviet national anthem. Their notorious act culminated in winning the WWF World Tag Team Championship from Barry Windham and Mike Rotundo at the inaugural WrestleMania in 1985, with the Sheik knocking out the future NWA Worlds Heavyweight champion Windham using Blassie’s cane.

By this time the Sheik’s performance style was theatrical and memorable, characterized by his catchphrase of “Russia Number 1! Iran Number 1!” and his distinctive physical appearance—a beer-barrel-shaped mound of muscle and menace. At WrestleMania III, they achieved a controversial win over the Killer Bees (the Sheik’s infamous feud with Blair would become a talking point many years later). Blair, reflecting on his team’s loss to Sheik in his autobiography, Truth Bee Told, points out that the bout did more to elevate the profile of lovable flag-waving lummox Jim Duggan, who intervened on their behalf to chase the bad guys with a two-by-four, than to bring attention to their own team. (Even though they had a heated history, when I texted Blair for a comment about the Iron Sheik’s death, he responded with a simple and poignant message: “I’m so sad about Khosrow.”) The Iron Sheik’s partnership with Volkoff lost the tag titles to the British Bulldogs—Davey Boy Smith and Dynamite Kid—on an episode of Saturday Night’s Main Event in May 1986, and they continued to feud with the Bulldogs through December.

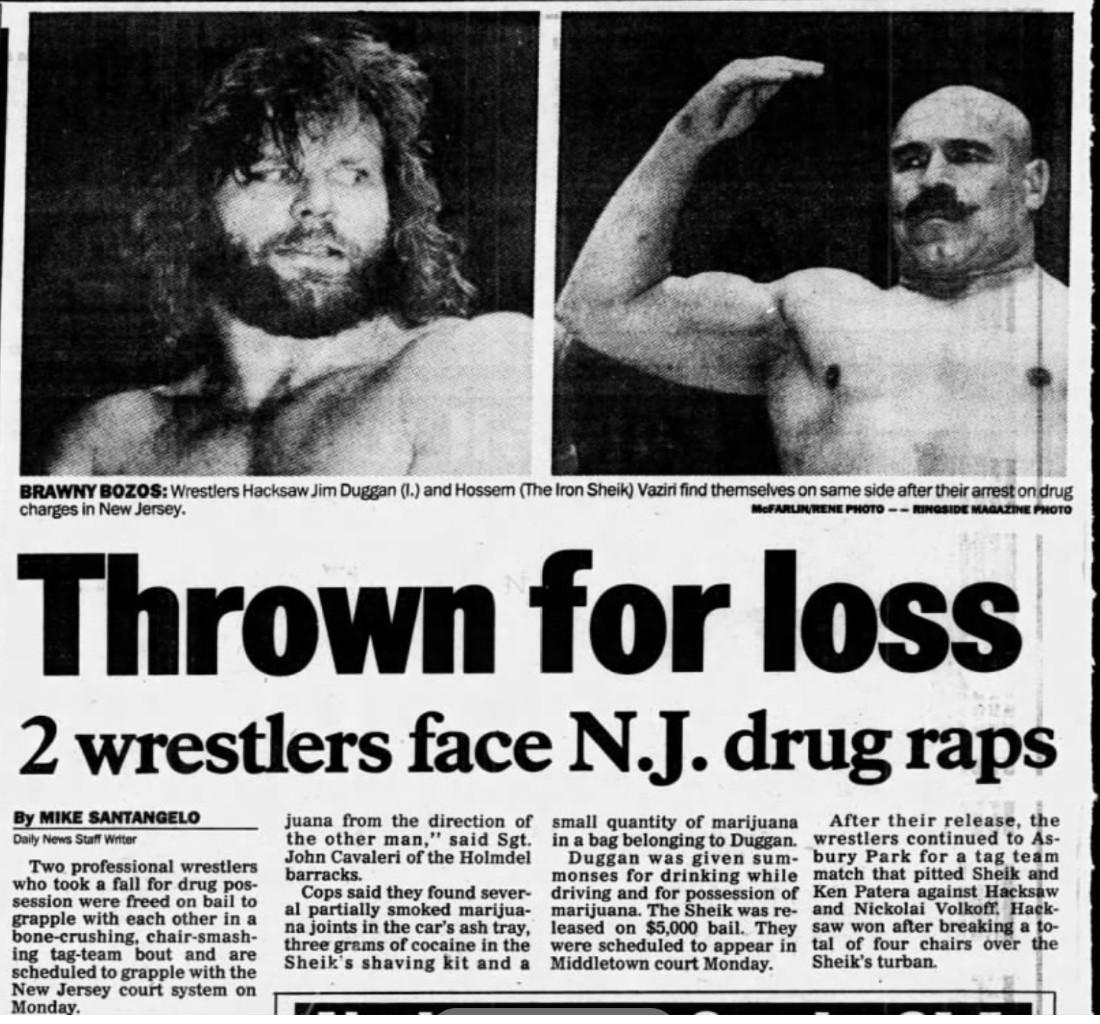

The Iron Sheik’s promising feud with WWF newcomer Duggan took a surprising turn on May 26, 1987. This change to their relationship was set in motion when Iron Sheik convinced Duggan to drive him to a show, as detailed in Duggan’s autobiography. Because Duggan knew that it was becoming less important to maintain wrestling story lines in public—the practice known as “kayfabe”—he agreed to drive him and even went along with the Sheik’s request to buy beers for the road trip.

Iron Sheik persuaded Duggan to act against his better judgment, and Duggan cracked open a beer during their drive. Duggan also enjoyed one of the marijuana cigarettes he’d brought along as they drove down the Garden State Parkway. His casual drinking betrayed him when he drove past a New Jersey state trooper and made no effort to conceal his beer.

The subsequent stop led to the search of their vehicle. Duggan admitted to the marijuana stashed under the driver’s seat. Further search led to a rather damning revelation when Iron Sheik was pulled out of the car. A vial containing two grams of cocaine dropped from what Duggan described as the Sheik’s “man-purse,” while a third gram of cocaine was discovered in the Sheik’s wallet. Both wrestlers were charged with drug possession.

Their arrest received widespread coverage in New York papers, including an article in the New York Daily News labeling them the “Brawny Bozos.” Subsequently, both men were fired from WWF, but Duggan was wrestling in house shows in June 1987 and the Iron Sheik reappeared in October 1987. However, the Sheik appeared heavier and slower and showed clear signs of the toll substance use and age was taking on him.

After several short tenures in different territories, the Iron Sheik landed in WCW in 1989. His time there included an entertaining feud with rising star Sting, complete with a Persian club–swinging competition that Sheik won. However, their encounter on WrestleWar in May 1989 was subpar; age and weight gain were evidently hampering the 47-year-old Iron Sheik’s performance.

Sheik’s last significant stint began in March 1991, when he returned to WWF as Colonel Mustafa, an Iraqi sympathizer aligned with U.S. turncoat Sgt. Slaughter and General Adnan (who, in his youth, had been an acquaintance of Saddam Hussein’s). Because the story line labeled Mustafa as Iraqi, no mention was made of Sheik’s old name or Iranian heritage. Their run peaked with a lackluster main event on SummerSlam 1991, after which Mustafa slowly wrestled his way out of the promotion, leaving in 1992.

After this run, the Iron Sheik transformed into a novelty act, endeavoring to keep earning money even though he was over 50. His later career featured a shoot-style match against Yoji Anjo in UWFi and a Nigerian tour alongside other fading stars organized by “Gentleman” Chris Adams.

He and Backlund managed the Sultan (the massive Rikishi, father of the Usos and Solo Sikoa) in WWF in 1996. Later, he comanaged Tiger Ali Singh with Ali’s father, Japanese wrestling legend Tiger Jeet Singh. However, his stint as a manager ended in 1997 because of another failed drug test. As Michael Hayes describes it, Sheik misunderstood the term “positive” to mean that he was drug-free, leading to a rather amusing anecdote about the Iron Sheik celebrating the result of his test.

The Iron Sheik’s final in-ring WWE highlight came in 2001 during the Gimmick Battle Royal on WrestleMania X-Seven. Despite his deteriorating physical condition, he succeeded in eliminating Hillbilly Jim to claim victory. The victory reportedly came about because Sheik was physically unable to take a bump outside the ring. However, his triumph was short-lived, as he was subsequently subjected to Sgt. Slaughter’s Cobra Clutch in the ring.

Throughout the 2000s, the Iron Sheik remained a volatile presence in the wrestling scene. He was known for his notorious outbursts at former colleagues, such as his tirade against the Ultimate Warrior, and for appearances on The Howard Stern Show. However, his personal life was marked by tragedy and struggle; he wrestled with cocaine addiction and grappled with the murder of his daughter Marissa in 2003. She was strangled at the age of 27 by her boyfriend Charles Reynolds, who confessed to the murder and told officers that he and Marissa had been taking pills. This dark period in the Sheik’s life resulted in his wife leaving him in 2007 as his own addiction worsened. She returned a few years later when he eventually stopped using cocaine.

According to Keith Elliot Greenberg, who cowrote the Iron Sheik’s unpublished autobiography (which Greenberg maintains is the finest unreleased wrestling autobiography ever written), the Sheik had planned to kill Reynolds in a Georgia courtroom. His family, however, prevented him, recognizing that despite his deteriorating physical condition, the Sheik still harbored enough rage and strength to follow through with his intentions. (Charles Reynolds died in 2016.)

In 2013, the Iron Sheik’s longtime friends and business managers Jian and Page Magen successfully crowdfunded the production of a documentary about his life, titled simply The Sheik. The documentary brought the Iron Sheik back into the limelight, with a focus on the Sheik a colorful fallen star who had dealt with hard times. The Magen brothers also managed the Iron Sheik’s Twitter account, turning it into a social media gold mine. They artfully captured the Sheik’s unique voice in tweet after tweet, often recycling many of his most distinctive comments.

This curious late-life revival of the Iron Sheik, masterminded by two media-savvy handlers who recognized the inherent marketing value of this grand old man, is one of professional wrestling’s more fascinating tales. It is possibly second only to the resurrection of Jake “the Snake” Roberts through Diamond Dallas Page’s emotional support and yoga teachings. Unlike Takhti, the Iron Sheik lived a long, albeit tumultuous life. He may not have won an Olympic gold medal, but as he stated years ago, “I can’t eat gold medals.” However, with two WWF championships under his belt and a new generation of fans who chuckled at posts written in his unique voice, he could certainly dine out for the rest of his life.

Oliver Lee Bateman is a journalist and sports historian who lives in Pittsburgh. You can follow him on Twitter (@MoustacheClubUS) and read more of his work at oliverbateman.com. He blogs, vlogs, and podcasts at his Substack, Oliver Bateman Does the Work.