Last Friday marked the midway point of Major League Baseball’s 2023 regular season. Fittingly, the scoreboard was a microcosm of the campaign’s topsy-turvy standings. The free-spending Padres, who’ve built much of their underperforming lineup out of pricey shortstops, lost in 11 innings to the penurious, riveting Reds, who (like the similarly exciting and even more miserly Orioles) promote a promising, underpaid shortstop every few weeks. Two Reds rookie shortstops, Matt McLain and Elly De La Cruz, drove in tying runs in extras to fend off the Friars, 7-5. Elsewhere, in a matchup between teams that (perhaps wisely) reconsidered signing Carlos Correa last winter, the deep-pocketed Mets succumbed to the Giants, 5-4. The big blow for San Francisco, a three-run, come-from-behind, game-winning homer, came courtesy of “somebody named Patrick Bailey,” as one Mets beat writer put it in a tweet that evoked View of the World from 9th Avenue. (Or Roosevelt Avenue, to make it more Queens.) Bailey, a 24-year-old, league-minimum-making catcher who was called up in mid-May, would rank third on the Mets in FanGraphs WAR.

On the same day, the Phillies fell to the Nationals, and the Angels lost to the upstart first-place Diamondbacks, despite the last and longest of Shohei Ohtani’s 15 homers in June. The Rangers and Blue Jays lost games, too. Of MLB’s seven highest-payroll teams, per Baseball Reference, not one emerged victorious. They didn’t all lose, though: The St. Louis skies opened up, sparing the Aaron Judge–less Yankees—who had a sub-.500 month, albeit with one perfect win—the possibility of a sweep of baseball’s biggest spenders.

Back on Opening Day, the league’s most expensive teams projected to be among the best. More than halfway through the season, it’s become commonplace for MLB’s high rollers to, well, roll over. The Mets and Padres—who combined for 190 regular-season wins last year, squared off in the playoffs, and then claimed two of the top four slots in offseason spending—are in fourth place in their respective divisions. The other two offseason splashers, the Yankees and Phillies (along with the high-spending Angels), are in third, while the perennial powerhouse Dodgers have just a 1.5-game lead over third-place San Francisco. With the exception of the Rangers, this season’s surprise teams all have payrolls that place in the bottom 10: the Rays, Orioles, Diamondbacks, Reds, and Marlins. Only two of the majors’ six first-place teams (Texas and Atlanta) have higher-than-median payrolls. Simply put, spending big hasn’t brought the desired results.

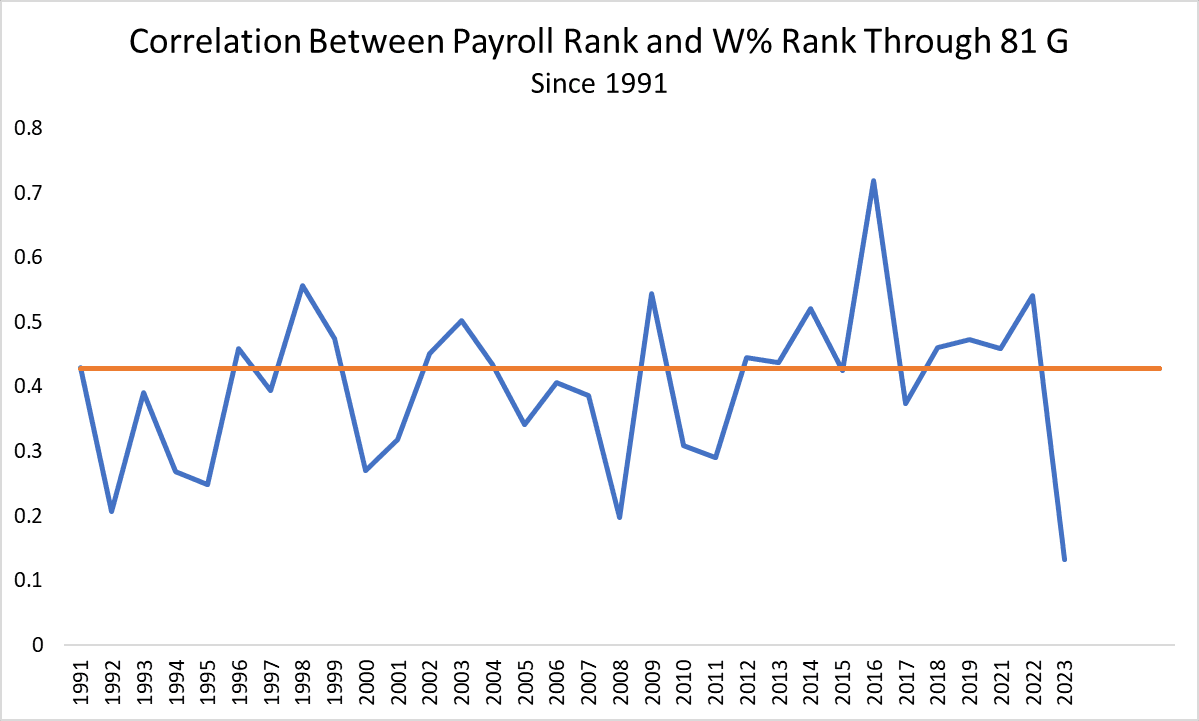

As Neil Paine noted last month, we can quantify how tenuous the link between dollars and dubs has been. After Saturday’s slate, all 30 teams had played at least 81 games, or half of their regular-season schedules. The graph below shows the yearly correlations between payroll rank and winning-percentage rank through each team’s first 81 games, beginning in 1991 (excluding the pandemic-shortened 2020 season). Correlations range from -1 (a perfect inverse correlation) to 1 (a perfect positive correlation). The higher the positive correlation, the stronger the relationship between two variables—in this case, where a team’s spending ranks and where a team’s winning ranks. The red line represents the median yearly correlation over these 32 seasons.

There’s no pronounced upward or downward trend over the full sample that would indicate an appreciable shift in how strictly spending dictates success. Last year’s correlation was on the high side. This year’s, however, is only 0.132—the lowest of the bunch—indicating an extremely weak link between spending and winning. This really has been a big year in baseball for eating the rich.

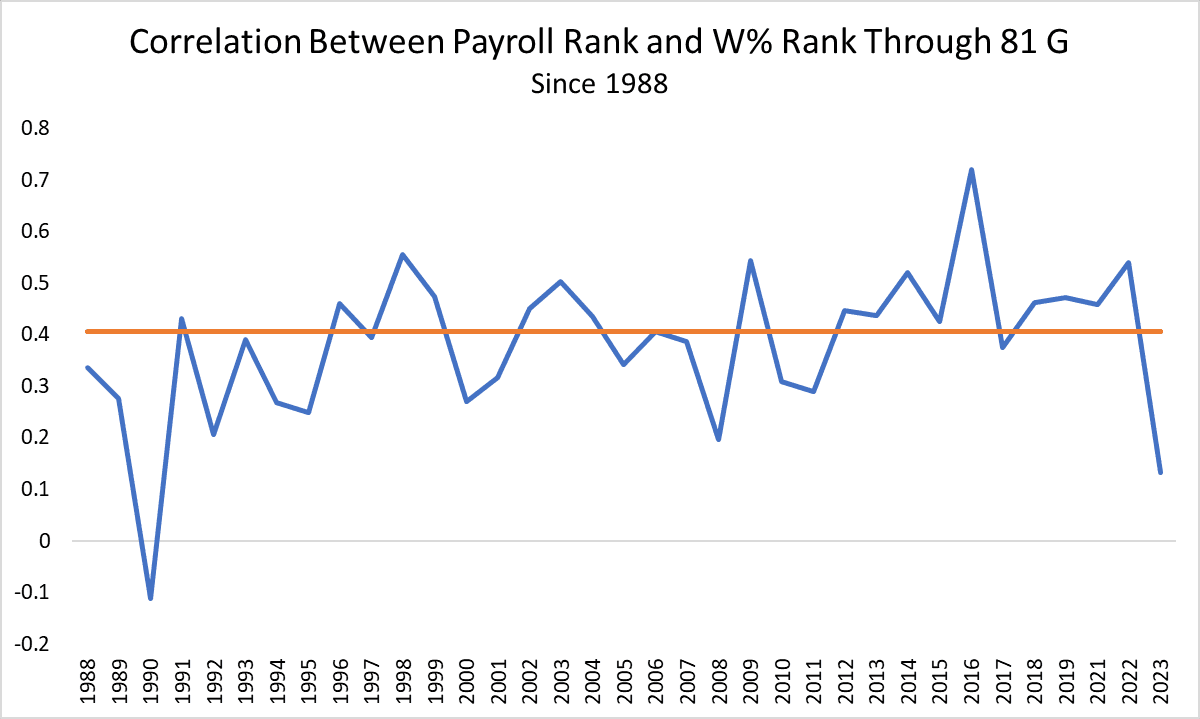

You may be wondering why that graph starts in 1991. It’s partly because the data gets less relevant and reliable the further back we go, but it’s also because 1990 was an even weirder year than this one.

In 1990, the correlation between payroll rank and winning-percentage rank was slightly negative: Teams that spent more tended to do a little worse than their frugal counterparts. Granted, the difference then between the most profligate and penny-pinching teams was narrower than it is now. And those wacky results weren’t mirrored in surrounding seasons. Still, things were wild during that one-year blip. In April 1990, Philadelphia Inquirer reporter Sam Carchidi wrote, “Maybe money can buy championships,” citing the contender or favorite status of the teams with their division’s highest payrolls: the Mets, Dodgers, Royals, and Red Sox. In the end, though, only one of those teams won its division. The Royals, baseball’s highest-paid team—there’s a blast from the past—started so slowly en route to a 76-86 record and a sixth-place finish in the AL West that general manager John Schuerholz (who would resign that October) said that May that no team had ever combined such high expectations and disappointing play.

The disconnect between expectations and outcomes continued through the 1990 World Series, as the low-payroll Reds swept the high-payroll A’s, featuring Rickey Henderson, José Canseco, and Mark McGwire. “The A’s are well known for their big spending,” columnist Joe Ostermeier wrote in late October, a contention that seems dated (to say the least) today. But his conclusion still rings true in 2023: The Reds’ triumph “shows you can’t buy a championship,” he noted, adding that “they still decide games by the numbers on the scoreboard, not the numbers on the players’ paychecks.”

That’s been abysmal news for the Mets and Padres, who started this season as playoff favorites and now look like long shots to land wild-card berths. It’s been fantastic news for the Orioles and Diamondbacks, who’ve followed the opposite path. But is it bad or good for MLB? Let’s consider the case for each side.

Bad for Baseball

The case that this season’s high-payroll (and high-profile) flops are bad for the sport boils down to the notion that it’s good when owners are incentivized to spend. Under previous, tighter-fisted ownership groups, the Mets and Padres were routinely embarrassing and stubbornly nondescript, respectively. Their increased spending in recent seasons—tangible evidence of their championship aspirations—has made them two of the sport’s biggest stories.

The Padres’ spending, in particular, became a kind of cause célèbre that stood counter to their rivals’ steady stream of bullshit about baseball ownership being a bad business. While commissioner Rob Manfred moaned about revenue disparities that were hamstringing teams in some markets and other owners and executives bemoaned “biblical” losses, announced a need to “align our payroll to our resources,” and downplayed the potential of their teams to justify meager investments in their rosters, Padres owner Peter Seidler preached about parades and warned of the risks of not bolstering his squad by, say, signing Xander Bogaerts. In February, The Washington Post labeled San Diego “MLB’s most fascinating experiment.”

What would be the consequences of that experiment’s failure? Well, plenty of people in ownership circles would be thrilled to dance on the Padres’ competitive graves—and the Mets’, for that matter. As the most aggressive clubs signed free agents for virtual eternities last offseason, the teams that stayed on the sidelines cast aspersions on the spenders. Rockies owner Dick Monfort complained that the Padres, Mets, and Phillies were putting pressure on him to spend: “What the Padres are doing, I don’t 100 percent agree with it,” he said. Manfred questioned whether the Padres’ approach was sustainable. And a number of anonymous executives grumbled that Cohen and Co. were breaking unwritten rules of austerity. If the Padres don’t win—and if their on-field mediocrity, coupled with the sport’s pivot to a less lucrative, post-cable-bundle broadcast model, really does make their spending unsustainable—fewer MLB owners would follow Cohen and Seidler’s lead, and a lot of anonymous sources would start spouting I-told-you-sos.

And, hey, they’d have a point. Although the Rangers owe their pole position in the AL West race in large part to expensive free-agent additions (Jacob deGrom and his season-ending injury notwithstanding), this season’s standings go to show that running a high payroll is neither necessary nor sufficient for fielding a winner. But it’s easy to imagine unscrupulous owners seizing on the struggles of a few teams with liberal budgets as convenient cover: Spending didn’t work for the Padres, so why would we raise payroll? In a sense, then, this anomalous season could provide an excuse for the Bob Nuttings and John Angeloses of the world to keep a tight grasp on their purse strings even when it makes sense for them to spend to supplement their talented, team-controlled cores. That might be a formula for fan frustration and future labor strife.

Good for Baseball

Counterpoint: Upsets and suspense are fun. The big spenders’ scuffles are unexpected, and as unpleasant a surprise as they’ve been for fans of those teams, fans elsewhere likely love watching payroll Goliaths get taken down by Davids. It was clear coming into this season that 2023 would probably bring improved parity to the league’s recently stratified standings. But because some of the favorites have stumbled as some of the underdogs have arisen, very few teams have built up big leads, and very few teams are simply playing out the string. While that may make the trade deadline less exciting (If everyone’s buying or holding, who’s left to sell?), it should also make for a fine pennant race. Entering Monday, only four teams’ FanGraphs playoff odds had zeroed out, and all but seven were still clinging to at least a 10 percent shot of cracking the expanded playoff field. In a zero-sum sport, one team’s lost hope is other teams’ gain.

Because MLB lacks a salary cap and payrolls vary widely, many fans believe the league has a problem with competitive balance. (A perception that smaller-market owners and the past two commissioners have wholeheartedly and disingenuously encouraged.) In reality, though, baseball’s competitive balance compares quite favorably to that of other major sports. Smaller markets don’t doom MLB teams to failure, and there’s a good deal of upward and downward mobility in the standings from one season to the next. If a few of this season’s favorites misfire, it may make it clear that while more money helps, all else being equal, the sport’s inherent randomness trumps the determinative power of payroll—and that’s before the pure randomness of postseason play adds an extra bulwark against the ability to buy titles. It’s tough to buy the argument that the Mets are breaking baseball if the Mets are broken themselves.

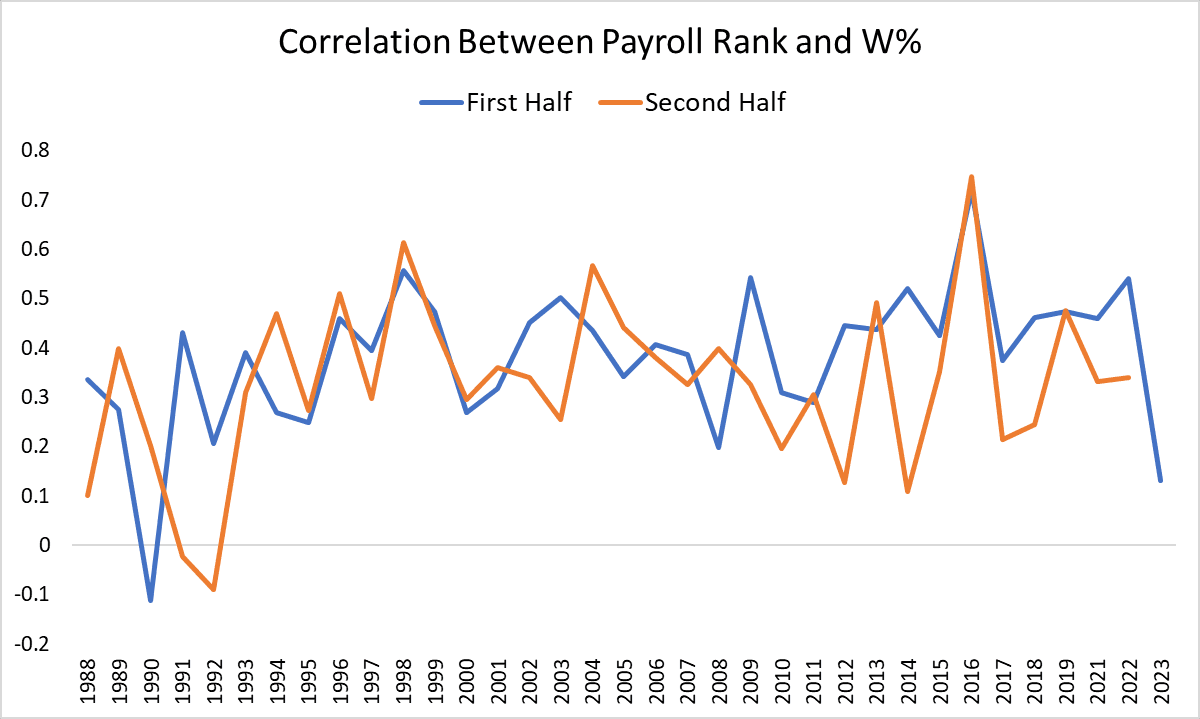

Of course, there’s still a lot of season left. The bad news for the likes of the Mets and Padres—who are hardly in the market for more bad news—is that historically, the correlation between payroll rank and winning-percentage rank has been a bit stronger in the first half of the season than in the second (likely because the composition of rosters evolves, or devolves, as the season goes on). The good news is that the relationship between a team’s payroll rank and winning percentage in the first half has little bearing on the relationship between its payroll rank and winning percentage in the second half. Over our full 35-season sample, the correlation between the two halves—yes, a correlation of correlations—is a fairly weak 0.39. In other words, the fact that the first half was wonky doesn’t mean the second half will be wonky too.

For now, Cohen and Seidler say they’re staying the course and banking on the true talent of the rosters they assembled. Per BaseRuns, at least, the oddly unclutch Padres have fallen several wins short of the record they “deserve,” based on their underlying performance. (So have the Rangers, which bodes well for their division title hopes.) Some surprise teams, meanwhile—the Orioles, Reds, Marlins, and Diamondbacks—have handily exceeded their BaseRuns records, which means regression could be coming. Even after flailing for a few months (to varying degrees), the Dodgers, Padres, Jays, Mets, and Cardinals rank second through sixth, respectively, in projected rest-of-season winning percentage. There just might not be enough season left for them to make up the ground they’ve lost.

It should be fun to find out. Which is why, after all the prognosticating, budget breakdowns, and fretting about the future of baseball, we fall back on the refrain sports pundits have been singing for the better part of a century: That’s why they play the games.

Thanks to Lucas Apostoleris, Jeff Euston, Ryan Nelson, and Neil Paine for research assistance.