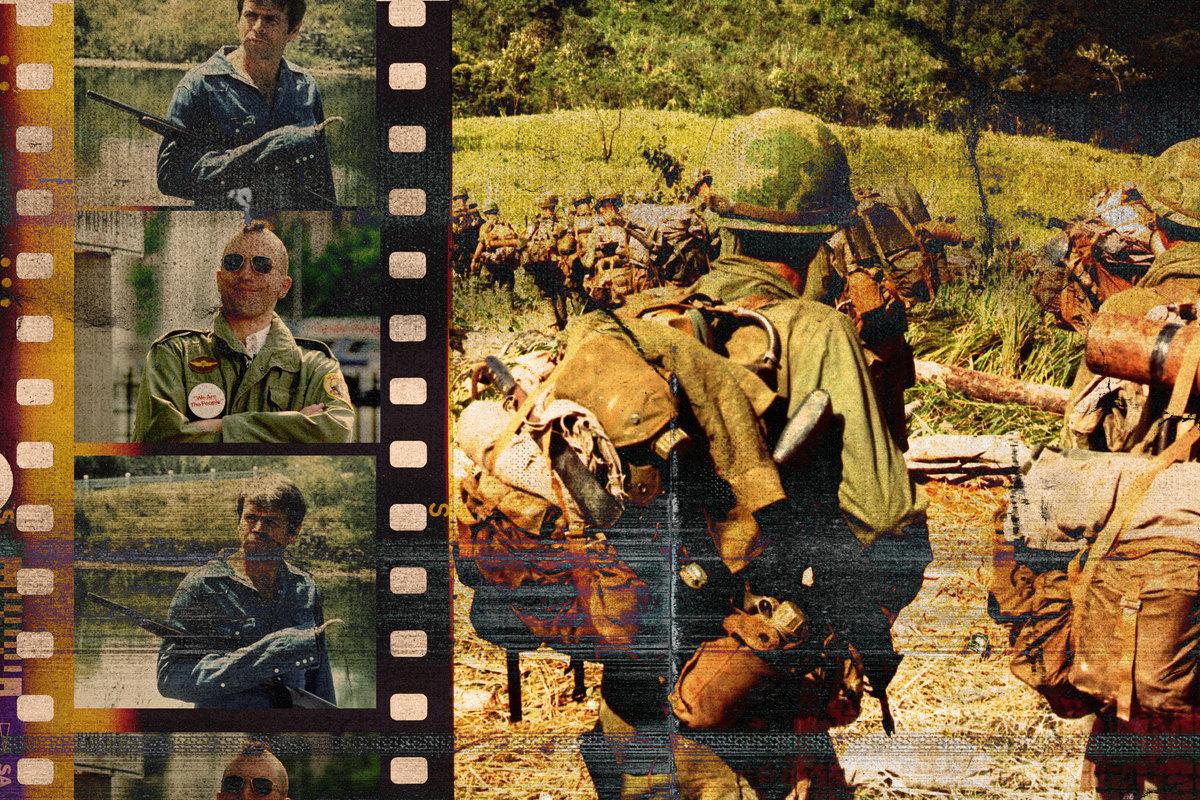

Episode 2: “I Just Don’t Talk About It”

‘Do We Get to Win This Time?’ is a podcast about how Vietnam movies have shaped the way we think about the Vietnam War. In Episode 2, host Brian Raftery looks at how mainstream Hollywood tried to dodge the war in the early ’70s—while a series of gritty underground films brought the combat to moviegoers across the country.

Do We Get to Win This Time? is a podcast about how Hollywood has depicted and defined the Vietnam War. You can listen on the Big Picture feed. The following is an excerpt from Episode 2: “I Just Don’t Talk About It.”

Frank Snepp first landed in Saigon in 1969. He was a journalist who’d recently joined the CIA, and for the next six years, Snepp worked as an analyst and counterintelligence officer.

It was an intense job, and Snepp would sometimes unwind with other Americans at a downtown hotel.

“We would watch movies on the roof as we looked out over the edge of Saigon,” Snepp says. “And there were firefights all along the horizon, rockets going into the night sky and what have you. … You’re not supposed to be carrying weapons, but oftentimes if a scene came on in a movie, you went nuts, somebody would take out a .45 and fire it into the air. “

One night, not long after his arrival, Snepp and his fellow Americans caught a showing of a recent British war satire: The Charge of the Light Brigade. It was based on a famously disastrous battle between British and Russian forces.

The events in The Charge of the Light Brigade were more than 100 years old, but to some of the Americans watching that night, the struggles of the British cavalry felt very relatable. Nearly 17,000 Americans had been killed in Vietnam in 1968 alone.

By the late ’60s, the conflict in Southeast Asia had become so ubiquitous, nearly every war film—no matter where or when it was set—became a parable for Vietnam. Sometimes, the connection was a coincidence. But a few anti-war filmmakers used older battles to explore the new terrors of Vietnam.

In 1970, a very different vision of the U.S. military was hitting theaters. It was a combative comedy, set in an American medical unit—a place where blood and booze flowed in equal measure.

Set during the Korean War—and directed by Robert Altman, who’d flown bombing missions in World War II—M*A*S*H is about as pitch-black as a comedy can get.

It depicts U.S. military men as bored, horny nihilists—hardly the image of American might that Hollywood projected in the ’40s.

The movie was so anti-war, executives at 20th Century Fox forced Altman to add on-screen titles, making it clear the movie was set in Korea. The studio worried audiences would think his Korean War movie was really a Vietnam War movie—which, effectively, it was.

With studios still nervous about addressing Vietnam head-on, directors like Altman had to look to the past, expressing their frustrations with the war via older American battles. The result was a series of downbeat films that took a strongly anti-war stance—without ever mentioning Vietnam.

Some movies went back to the first World War, like Johnny Got His Gun, a 1971 drama starring Jason Robards about a gravely injured soldier flashing back to his life—a film Metallica would later sample in the nightmarish video for its hit song “One.”

Other Vietnam allegories came in the form of Westerns—none as brazenly, nor as brutally, as 1970’s Soldier Blue. It billed itself as “The Most Savage Film in History!” and starred Candice Bergen as a white American woman who takes up with a group of Native Americans. After surviving a grisly battle, she’s escorted back to a U.S. military camp—against her will—by a naive U.S. cavalry officer.

Soldier Blue director Ralph Nelson, like Altman, was a World War II veteran. But Nelson had toured the refugee camps in Vietnam, and had become opposed to America’s involvement in the war. He’d grown tired of the myths that had dominated Westerns, in which Americans were the de facto heroes, and Native Americans the automatic villains.

Nelson was also frustrated by one of Hollywood’s most beloved mythmakers: John Wayne, whom Nelson dismissed as “a great American hero who never fires any bullets, and never has any bullets fired at him.”

So Nelson ended Soldier Blue with a gruesome battle sequence—based on real events—in which U.S. cavalrymen slaughter countless Cheyenne women and children. It’s a truly nightmarish scene—one that can still make you wince, more than 50 years later, as you watch the cavalry leader call for an entire civilization to be destroyed.

As upsetting as the film’s final moments are, even those who turned away from the screen understood Nelson’s thinly disguised metaphor: The cavalrymen were stand-ins for Americans in Vietnam, while the Cheyenne were the Vietnamese.

Soldier Blue would have been a shocker no matter when it was released. But the movie took on a greater urgency during filming.

While on set, Nelson heard about an incident that would soon stun the world: The My Lai massacre. In 1968, U.S. forces had killed hundreds of unarmed Vietnamese women and children—an incident the military was able to cover up for more than a year and a half. But the horrors of My Lai eventually became public, thanks to newspaper reports and television broadcasts.

By the time Soldier Blue was released, America was still reeling from My Lai—which may be why the film’s ending provoked such strong reactions. At one sneak preview in New Jersey, nearly 200 people marched out of the theater, and several angry patrons stormed the box office, demanding refunds.

Maybe they were put off by the film’s violence. Or maybe they didn’t want to be reminded of the war their country was fighting thousands of miles away.

Whatever the reason, their response proved what some in Hollywood had long suspected: Audiences wanted nothing to do with Vietnam. As one offended viewer told the press: “We just weren’t ready for the atrocities.”

This excerpt was edited for clarity. Listen to the rest of the episode here and follow the Big Picture feed on Spotify.