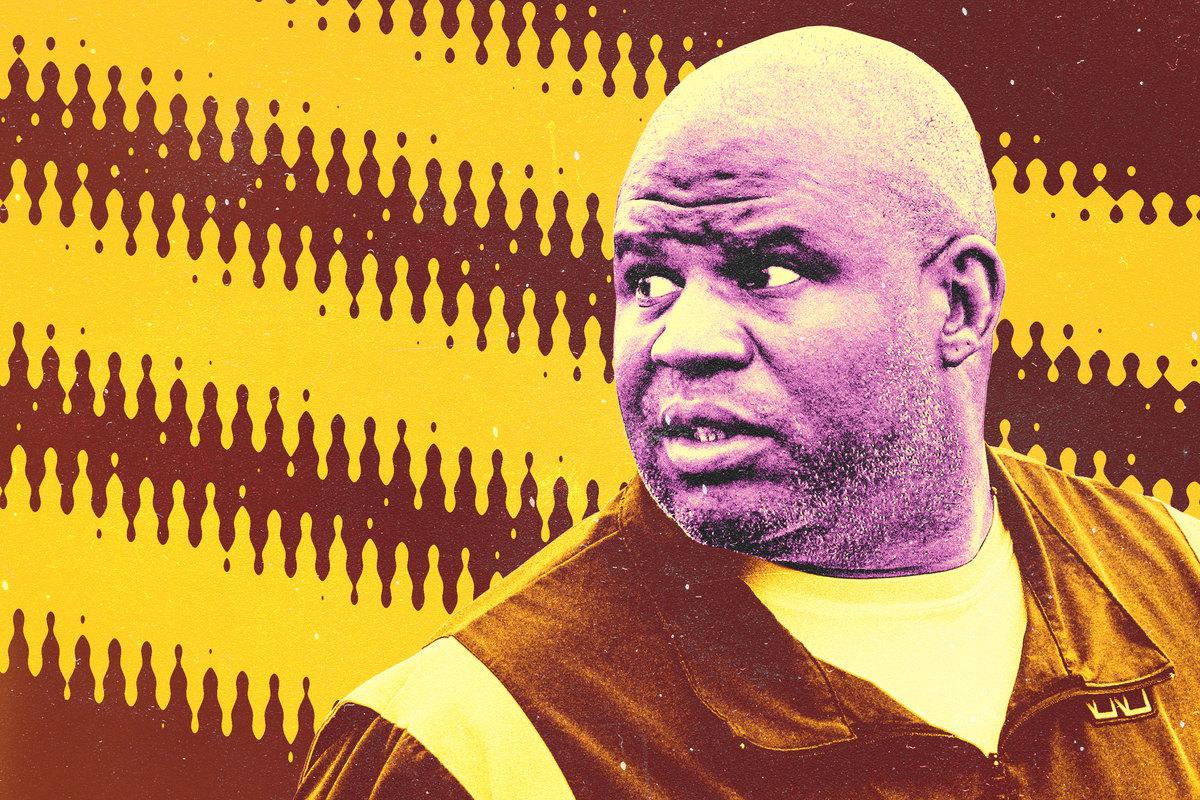

It’s not even 10 a.m. on a recent Monday and Eric Bieniemy is already sweating through his Commanders-issued pullover. To be fair, it’s an obnoxiously humid day in Northern Virginia—the kind of day when nobody wants to be outside and everybody is looking for a reason to be irritated. And Bieniemy, who left his cushy post as the Chiefs offensive coordinator six months ago to take the same job with the Commanders, has found plenty of reasons.

“So that’s it, huh?” Bieniemy asks his offensive line after a particularly rough showing in 11-on-11s. “I guess we’re just going to get our asses whooped all day?”

It’s not just the offensive line. “Too many balls on the ground,” Bieniemy says to the wide receivers after what feels like the 10th drop of the day. “Get your ass out of there and get set!” he yells toward the quarterbacks as they take too much time in the huddle. “If he doesn’t block, he’s not going to play,” he calls to a tight ends coach after an undrafted free agent botches a blocking assignment that spoiled a run play.

It’s been a long day for Bieniemy’s group going up against Washington’s formidable defense. The offense is young and inexperienced and still in the early stages of learning a new system. The defense, meanwhile, finished ninth in DVOA last year and boasts one of the best fronts in football. The mismatch in the trenches spoiled a lot of the plays Bieniemy called this day—and as the field clears for a special teams drill, Bieniemy is still voicing his displeasure with the offense. “Special teams, c’mon. At least we can do that shit right,” he says before convening with head coach Ron Rivera on the sideline.

This scene is a familiar one for anyone who’s attended Commanders camp this year. It’s only my second visit, but the sound of Bieniemy’s calls for his team to “GET SET” and “FINISH” is already seared into my brain. Even before taking the job in Washington, which also includes the assistant head coach title, Bieniemy had a reputation for being a yeller. And it appears it’s well earned.

“He’s gonna come at ya,” Andy Reid said in a March interview, speaking of his former assistant after Bieniemy joined Rivera’s staff. “He’s going to challenge ya. I mean, it’s healthy. Nothing wrong with that.”

But this season, Bieniemy isn’t on a team that has had proven success and employs one of the NFL’s great quarterbacks. Plus, he’s calling plays for the first time, filling a hole in his résumé that some have used to explain why he hasn’t been given a head-coaching job. This will likely be Bieniemy’s most challenging season as an offensive coordinator yet. And his approach so far has stirred up a bit of drama in Ashburn.

Just days before Washington’s first preseason game, Rivera told reporters that a few Commanders players had come to him with “concerns” about Bieniemy’s unrelenting coaching style, which is a big departure from what they saw under former coordinator Scott Turner last season. “I had a number of guys come to me, and I said, ‘Hey, just go talk to him,’” Rivera said. “I said, ‘Understand what he’s trying to get across to you.’ I think as they go and they talk and they listen to him, it’s been enlightening for a lot of these guys. I mean, it’s a whole different approach.”

Naturally, the “concerns” comment drew a lot of attention, and Rivera clarified his words with a statement the following day, saying he was happy with the work Bieniemy was doing and that the media was making “a little more than needs to be made of this.”

But even if this all was just early camp fodder that will soon be forgotten, it did reveal a truth about Bieniemy’s latest stop: His success or failure in Washington—and whether it leads to one of those 32 jobs that have so far eluded the seemingly overqualified assistant—won’t necessarily be dictated by his capacity to call plays or design an offense of his own. Instead, it will be about seeing the bigger picture and getting players to buy in. If he can turn Terry McLaurin, Jahan Dotson, Antonio Gibson, and Brian Robinson Jr. into even a league-average offense, that would make Washington a playoff contender in a weak NFC and give new ownership an ideal candidate to replace Rivera whenever that time comes. If he fails, that could set his personal goals back years. It’s not a stretch to call this the most important season of Bieniemy’s coaching career—and none of this is news to him.

When I catch up with Bieniemy after practice on a Tuesday, he doesn’t seem very interested in talking about the evolution of the Chiefs offense. I can’t blame him. Hours earlier, his boss told the media that his coaching style may be rubbing some players the wrong way, and he had just spent the last 10 minutes fielding questions about that during his post-practice presser.

I figured I’d ask the question anyway: With every defensive coordinator in the NFL focused on stopping Patrick Mahomes, how did the Kansas City staff manage to stay ahead of the curve? It’s the second time I’ve asked Bieniemy this question in the last six months. The first was in February, days before the Super Bowl, and he explained to me that it “always comes down to just making sure we’re creating the matchups and putting our guys in [the best] position.”

That wasn’t the illuminating answer I was hoping for at the time, so I decided I’d ask him again with the hope that he’d be more open to providing insight into Kansas City’s process now that he had switched teams. Maybe he’d tell me about some new package the Chiefs had installed to combat the tactics they were seeing. Maybe there was an anecdote to explain how Mahomes became a more disciplined passer. There had to be some nugget that would get the x’s and o’s nerds all riled up, right?

Instead, Bieniemy credited the Chiefs coaching staff with building an environment where communication was prioritized. Not just being in constant dialogue about the ins and outs of the team, but also developing a common language to aid that communication. He talked about building a foundation where coaches could collaborate and then relay what they’d discussed to the players. There was nothing about play designs or finding counters to the counters. Just the kind of stuff you’d hear during a Zoom meeting for your typical desk job.

Bieniemy wasn’t shying away from play-calling talk, even though that’s been cited as the reason he’s been passed over for bigger jobs. (Whether that’s the real reason he is still a coordinator is up for debate.) Yes, Reid called plays during Bieniemy’s time in Kansas City, but it doesn’t feel like a point of insecurity for the coach. There are numerous accounts of Bieniemy’s key tactical contributions to the team, including his role in the game-winning touchdown call in the Super Bowl and his coaching point that helped seal the win. He just doesn’t seem to think the whole play-calling thing is that big of a deal.

“There’s a lot that goes into being a coach, right?” Bieniemy told me when I brought up the media’s focus on his lack of play-calling experience. “Because not only do you have to be a leader, you have to be a role model. Sometimes you got to be an uncle [and] be an ear for a guy. Sometimes you got to be a disciplinarian. Sometimes you got to be a teacher. Sometimes you got to be a provider. So you have to wear all the hats. And then on top of that, you got to be a leader.”

Bieniemy will wear even more hats in Washington than he did in Kansas City. In addition to his job as offensive play caller, he’ll also serve as assistant head coach. Rivera says the role was designed to help Bieniemy develop the skills needed to be a head coach. “There’s been a little bit of mentoring,” Rivera says, but supplying his new OC with “practical application” has been the main goal. That includes having Bieniemy schedule and script practice, which is a bigger deal than it may sound.

“That’s one of those things that you, as a head coach, really do dive into, … and Eric, he’s changed some of the things we’ve done in the past,” Rivera says. Some of those changes may have led to the “concerns” some players had voiced, but the head coach says those changes have been for the better.

“We’ve had a couple bumps,” Rivera says after Monday’s practice. “But as we smooth it out, I can see exactly where he’s going with that and what he’s trying to accomplish.”

Both Rivera and Bieniemy have said they are pleased with the progress the offense has made during camp, as it appears the tough coaching is starting to get through to the players. But this unit has a long way to go before it will draw any comparisons to the offense Bieniemy coordinated in Kansas City. And ultimately, the on-field results will be the most telling.

The Commanders offense finished 28th in DVOA last season, which is why the team missed out on the playoffs despite fielding a top-10 defense. The main culprit was an ineffective passing game, led by the predictably erratic Carson Wentz, who eventually lost his job to the equally erratic Taylor Heinicke. The quarterbacks were bad, and any offensive coordinator would have struggled to work around them, but former OC Turner did not make their jobs any easier.

Turner is a younger play caller, but one who comes from old-school roots, having previously worked under his dad, longtime offensive coordinator Norv Turner. That old-school thinking showed up in Washington’s play-calling tendencies last season. Turner called runs at a high rate in what was likely an attempt to control the clock and protect his quarterbacks. But that actually had the opposite effect: Because Washington’s running game wasn’t efficient (26th in success rate), the limited dropback opportunities the quarterbacks got came in obvious passing situations, when the degree of difficulty was at its highest. Thanks to all that running, the Commanders led the NFL in time of possession, which was once seen as a key factor in winning football games, but they averaged only 18.9 points a game.

Simply calling more passing plays on early downs should help improve this offense and yield better results (even if the quarterback situation hasn’t significantly improved, with Sam Howell and Jacoby Brissett battling for the starting gig). A high early-down pass rate had been a notable feature of the Chiefs offense under Bieniemy’s watch, so that should be one of the expected changes.

Based on what Washington has been practicing, expect pre-snap motion to be another big feature of the offense. In the team’s preseason opener, Washington used pre-snap motion on nearly every snap, and throughout camp, Bieniemy has been on his offense about getting set at the line of scrimmage early enough in the play clock to allow enough time for many of the tricks we’ve seen Kansas City use over the past few years. I wasn’t keeping an official count, but I think I heard Bieniemy yell “GET SET!” about 50 times over the course of two 150-minute practices.

In fact, most of Bieniemy’s on-field talk at practice was centered on what was happening before the snap. And when you watch his old Chiefs offenses on film, it’s easy to see why: That’s where a lot of the magic happens. The actual core concepts behind the plays are fairly routine—there are only so many ways you can have Travis Kelce run an option route or Tyreek Hill run a deep over. But what makes the offense so effective is the use of pre-snap window dressing and shifts to disguise plays and create favorable matchups. The Chiefs do a lot before the snap so they don’t have to do too much after it.

Those choreographed routines take time to execute, though. So to run them, the quarterback has to get the team in and out of the huddle in a timely manner; the offense has to get lined up and set as soon as possible; and there can’t be any mistakes in alignment or any confusion about the snap count. That seems to be the point Bieniemy is trying to get through to his new squad: Before you can have all the fun the Chiefs offense seems to be having, you have to endure these miserable days on the practice field.

For Bieniemy, this is “the fun part” of the job: challenging players, in his words, to become “comfortable with being uncomfortable” and seeing them come out on the other side as improved players and people. That, he says, will be more important than any plays he calls. “This is the beauty about what we do,” Bieniemy says. “This is why most coaches love what we’re doing, because we love wearing all these hats. There’s more to being a coach than just calling plays.”

It’s clear at this point in our conversation that Bieniemy just wants to get out of this heat and retreat into his air-conditioned office, where there’s more work to be done. But before he leaves, he dons a confident smile and tells me one last thing:

“Yes, I can call plays too.”