The Making of Bray Wyatt

Windham Rotunda, who died Thursday at the age of 36, was born into the wrestling business. This is the story of his life, as told by his family and by Windham himself.Editor’s note: Portions of this article have been adapted from interviews conducted by Ian Douglass and Mika Rotunda for what was originally intended to be a Windham family retrospective. Douglass and Oliver Lee Bateman collaborated on this look at Bray Wyatt’s life and times.

Bray Wyatt—born Windham Rotunda and recognized globally for his personas as the Eater of Worlds, the Fiend, and the eerie Wyatt Family leader—died this week at the age of 36. He left behind his fiancée, JoJo Offerman, and four children. Rotunda was part of the esteemed Windham wrestling dynasty, which included his grandfather Blackjack Mulligan, who dominated the ring in the 1970s and 1980s; his father, Mike Rotunda (a.k.a. “Michael Wallstreet,” “Captain Mike,” and “Irwin R. Schyster”), a multisport star at Syracuse University who starred in WCW and WWF in the 1980s and 1990s; his uncles Barry and Kendall Windham, both of whom made lasting contributions to the sport; and his brother, Taylor Windham, who worked alongside him in WWE as Bo Dallas. As a third-generation star with a brilliant mind for all aspects of the wrestling business, Wyatt spent 13 years enthralling fans with his intense and unpredictable in-ring performances, as well as with his psychologically complex and captivating character work.

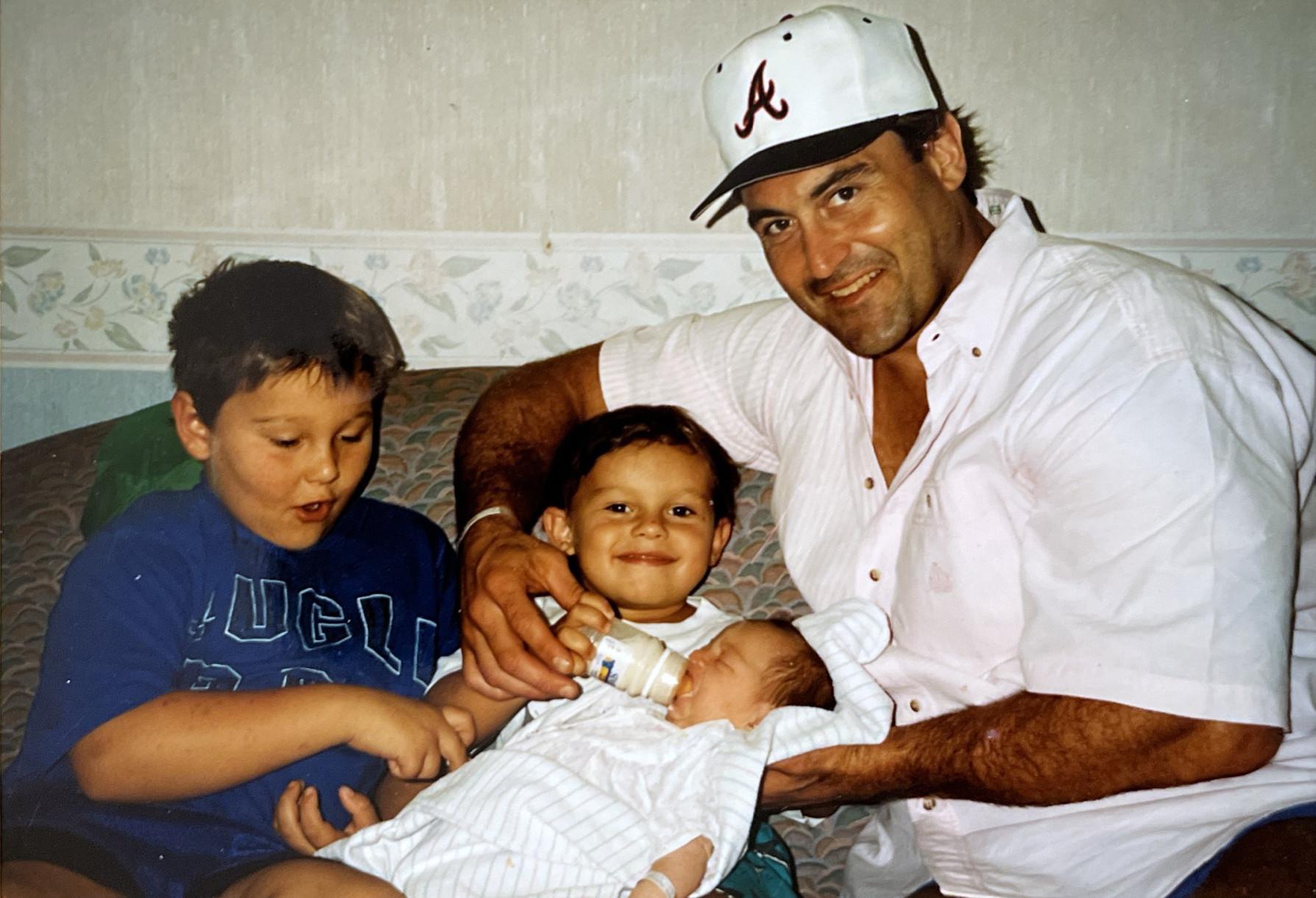

Long before he assumed larger-than-life proportions at the height of his WWE career, Wyatt’s entrance into the world was itself a dramatic event, reflecting the unpredictable and hectic nature of the wrestling universe he would later inhabit. Windham weighed a substantial 10 pounds when he was born on May 23, 1987—the sort of size that necessitated that his mother, Stephanie, Blackjack Mulligan’s daughter, undergo an emergency C-section. His father, Mike, had just wrestled Ric Flair in Jacksonville and rushed home to discover that Stephanie had already been driven to the hospital. The very next night, with Windham safely delivered, Mike went straight back to work to wrestle against Dory Funk Jr. in Orlando. Thus, Wyatt’s birth was bookended by back-to-back matches his father fought against a then-current NWA champion and a former champ, an early sign of the young Rotunda’s destined place in wrestling history.

After Stephanie had Windham, she decided she didn’t want her son or any of her future children to endure the same nomadic lifestyle that typified her years growing up as Blackjack’s daughter. “I didn’t have a whole year in the same school until I was in the eighth grade,” Stephanie said.

“When we were traveling with Windham, I said, ‘It’s time for Windham to start school. I want to stay still,’” Stephanie said. “We took a Sunday drive, we found a place, and I said, ‘I want my kids to have this place to call their home.’”

Home was Brooksville, Florida, a town north of Tampa with fewer than 9,000 residents. In 1984, three years before Windham was born, Stephanie had called her brother Barry to tearfully declare that she was sick of Texas, where she was living at the time. Barry was living and wrestling in Florida, and he immediately invited her to travel there to stay with him. In Florida, Stephanie met and fell in love with Barry’s best friend, Mike Rotunda, and after Windham was born, they decided to settle down in the unassuming Brooksville in the state where they’d first met.

Mike and Stephanie purchased 10 acres in Hernando County and decided to build a home there. That home would establish the small-town roots of all three of their children: Windham, Taylor, and Mika.

“If you grew up in South-Central [Los Angeles], everyone knows about it,” Windham explained in March 2023. “If you grow up somewhere like Texas, there’s places that have stigmas. But this is a place that nobody knows about. And I can tell it just kind of hardens your edges.”

Not only did the relative obscurity of his hometown help to hone the future Fiend’s edges, but the distinct challenges of dwelling there also served to figuratively sharpen the blade.

“It took 15 minutes to get to a gas station, and the road was rough and never graded,” added Windham. “And it rains every day in the summers in Florida. So the white limestone road would be washed out and destroyed. It was a daily problem for us dealing with that road alone. Not to mention the nasty chicken farm smell. And when I was old enough to wait for the school bus, in middle school, it was like I would be out there with these other kids, where we would walk up these mile-long driveways and all be at the same stop. It was just the perfect place for us to have fistfights and see things my kids have never seen. It was just a different time and a different place. And even when I explain it like that, most people don’t understand what it was actually like.”

Mike and Stephanie wanted to provide their children with a semblance of the normalcy and privacy that they believed was crucial for proper social development. What they may not have factored in was precisely how much the peculiarities of their children’s small-town environment would shape their lives and influence their eventual wrestling careers.

“I think it had a huge impact on my overall view of everything,” said Taylor. “From starting how I did and not knowing how different it was to be in a small town, and then realizing how crazy this little town that we grew up in was!”

That’s not to say that there was anything fundamentally ordinary about the Rotunda household, though. After all, when there are action figures of your dad and your uncles lying around the house, it’s only natural that the children will ask questions.

In a telling anecdote that captures the unpredictable nature of the wrestling business, Windham’s father shared a memory from a 1993 TV taping in Poughkeepsie, New York. As Mike wrestled in the ring as Irwin R. Schyster, the Steiners and Pat Patterson teased the then-6-year-old Windham in the locker room. The situation escalated when Windham pulled a pencil from Patterson’s shirt pocket and stabbed him in the forehead.

“As soon as I arrived, everyone told me the story about how Windham had stabbed Pat. It would have been awful for Windham to have stabbed any of the wrestlers or crew members there, but Pat actually had the power to fire me if he’d wanted to,” Mike said. The situation was defused when Patterson himself conceded it was his fault.

This, for the Rotundas, was everyday life. “I don’t know what it’s like to not have your dad’s action figure or your uncles’, but I loved it and it was never weird to me,” Taylor said. “It just kind of felt like the family business that I was eventually going to get into.”

Taylor accepted his destiny as the next link in a wrestling lineage early in life. At the age of 10, he would invite his best friend Fernando Gomez over to the house, where they scripted and performed their own SmackDown and Raw events in the Rotunda family living room. Occasionally, he recruited his little sister, Mika, to display her ring announcing abilities and to execute occasional Banzai Drops.

Mike and Stephanie both recalled that Taylor spent hours in front of the mirror of his childhood bedroom, working on his Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson impression and perfecting “the people’s eyebrow.”

“Taylor was probably destined [to wrestle] because he always acted it out and did it,” said Stephanie. “Windham had a very colorful personality.”

While Taylor was obsessed with the execution of professional wrestling matches, Windham’s love of sports was accompanied by fanciful pursuits including his passion for art and theatrics. When Mike departed to go on wrestling tours with companies ranging from WWF and WCW to New Japan Pro–Wrestling and All Japan Pro Wrestling, Stephanie would take the kids to pick out $1 movies from Movie Buffs—the small stand-alone movie rental store in Brooksville. Windham gravitated toward horror films and watched and absorbed every indie horror movie he could get his fiendish mitts on.

According to his father, this research paid off in a big way. “He took some elements from his real life and some of the things he saw other people experience in Brooksville and hit a home run,” Mike said. “He always loved horror movies. He loved Pee-wee Herman, who was squirrely as hell. Another of his favorite films was Beetlejuice. I thought Bray was one of the most creative characters I’d seen in a long time. Windham was always an excellent communicator with tremendous stage presence. He watched and studied a lot of horror films when he was younger, and he understood what it took to create a creepy vibe. He would pull elements from different characters and come up with a completely new thing.”

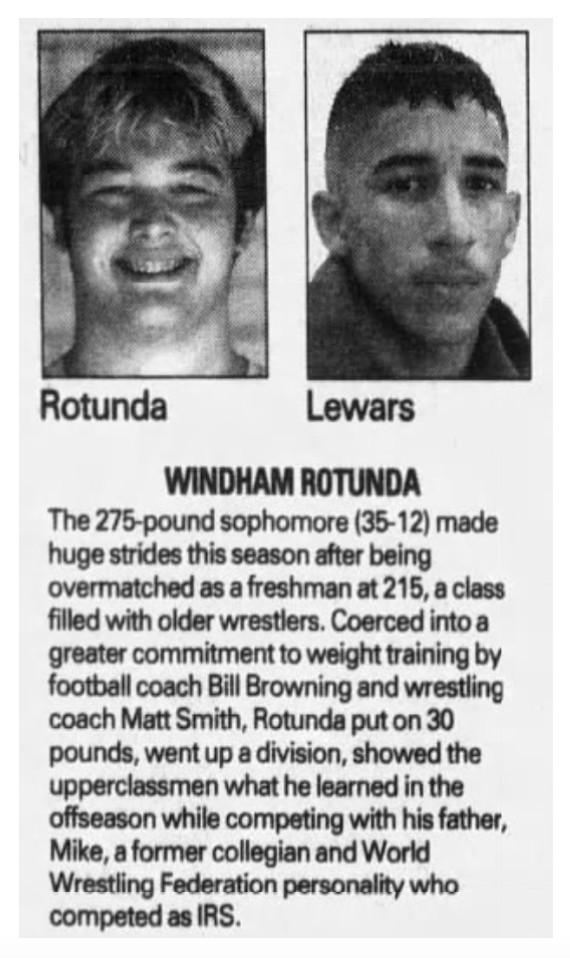

Throughout their high school years, Windham and Taylor each tallied an exhaustive list of multisport accomplishments similar to those of their famous father. Yet both boys were interested in pursuing professional wrestling.

One particular event underscores the young Windham’s determined character and rebellion, which would later become a hallmark of his wrestling persona. After winning the state wrestling championship, a triumphant Windham sought to commemorate the victory with a tattoo, a request his father firmly denied. Unperturbed, Windham then asked whether he could get his ears pierced, only to be met with another refusal. In an act of defiance, Windham got them pierced anyway, setting the stage for a chain of events that put him in the hospital.

“They wanted to pull him into nationals,” Mike said, “and he went to wrestle on the mat with an open wound from his piercing. He came in and was lying in his room, coughing. Then he came out and went over to Stephanie and told her that he thought he’d just coughed up a lung. Stephanie took Windham to the emergency room, and he was diagnosed with MRSA. His lung collapsed while he was in the hospital, and he couldn’t breathe. We almost lost him. He’d been voted the prom king, but he missed the actual prom. He spent all that time in the hospital. The whole thing with the piercing and the MRSA infection wouldn’t have happened if the mats had been cleaned properly.”

Windham’s youthful disobedience aside, Stephanie and Mike tried to enforce the house rules. “It was told to the boys, ‘If you’re going to do this business, you’re going to get your college education. Then you can do it,’” Stephanie said. “That’s what we made Windham do. Windham went to college. When Taylor graduated, his things were packed, and he was literally headed off to college to play football that weekend.”

As a prelude to college attendance, Taylor accompanied his father and Uncle Barry—two of the four men who carried championship gold into the very first WrestleMania—on a weekend work trip as they performed their duties as WWE agents. During that excursion, WWE vice president of talent relations John Laurinaitis spotted Taylor. Soon after, Laurinaitis offered him a developmental contract that would have required Taylor to relocate to Japan. Much to the initial chagrin of his parents, Taylor accepted.

Against his parents’ protests, echoed by those of his older brother, who had adhered to the family requirements and dutifully enrolled in college, Taylor began his WWE tenure—not in Japan, but at the Florida Championship Wrestling developmental system in Tampa. Once there, the newly minted high school graduate sat under the tutelage of Steve Keirn, Dusty Rhodes, and other experienced trainers.

Since his younger brother wasn’t obligated to adhere to the crystal-clear provisos imposed by their parents, Windham abruptly discontinued his attendance at Troy University in Alabama just before his senior year. Soon, he made his own entrance into WWE’s Florida-based developmental territory.

By 2009, both Windham and Taylor were signed to contracts with WWE. While many would assume that inheriting robust slices of Windham and Rotunda DNA would provide the third-generation fledglings with a preferential path through WWE, Taylor insists that no such way forward ever presented itself.

“You know, going in, I think both of us thought that it was a benefit for sure, but lots of pressure,” Taylor said. “As it went on, the pressure didn’t go away, but it changed because there was so much pressure on us to fill these big shoes of relatives who have been part of the legacy of the entire wrestling business. It ended up helping us develop characters that are so different that we ended up developing our own footprint because we didn’t just want to be just like our dad, our uncle, or our grandfather. We wanted to make our own impact, and at the time, they didn’t really want to use a generational name. That was almost not allowed.”

WWE refused to allow Mike’s children to capitalize on the Rotunda surname. In essence, the Windham-Rotunda lineage, which Taylor described as a “golden ticket” stuffed into both his and his brother’s back pockets, was never something they could pull out and leverage. Even so, Windham also described feeling the immense pressure and dreadful motivation that came with upholding the family dynasty while trying to establish a name of his own.

“It was a never-ending weight on my shoulders,” Windham said. “Every article ever written about me until I was 24, 25, or 26 years old. Every article written about me, the first two paragraphs were about everyone else in my family. That was the intrigue. You grow up your whole life with people going, ‘Hey! Are you going to wrestle one day?’ No! I’m going to do it my way. I am going to do it like this. All I ever wanted to do was be something. And not only be something, but be the best at it.”

Mike wasn’t surprised that his children inherited the mindset that mediocrity isn’t something to settle for. He gives much of the credit to Stephanie for instilling that spirit in their kids while he was traveling the roads of North America and Europe—or when he was wrestling for months at a time in Japan during the latter stages of his in-ring career.

“If anything, our kids grew up looking at Stephanie and I, and we never sat around and rested on our laurels. It was always go, go, go,” Mike said.

Watching his father take on a wrestler’s responsibilities also helped Windham learn the pro wrestling lifestyle.

“I only remember in my childhood that Dad leaves. He goes to Japan and says, ‘Take care of your mom.’ Or he goes to Japan—to wherever—and he is gone,” Windham said. “And right when he comes home, he sleeps for half a day and then is right back in the gym. So it’s from him, I think, I garnered that discipline. I don’t sleep. When I come home, I’ll rest for a little bit, but all day I am writing with the writing team and then I am at the gym at night. So it is like that discipline that we have—that ‘Let’s go to wrestling practice on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day’ kind of discipline has never really gone away.”

It wasn’t just the discipline that made the Rotunda family unique. Their wrestling bubble gave the kids some unusual ideas about the rest of the world.

“We believed that everyone was a wrestler,” Windham laughed. “So when people went to work—when my grandma went to work—we thought that she went to wrestle and got bloody in a cage or something.”

And you know how the classic saying goes: like father, like son.

“I know that he knows his mom wrestled. I know that he knows Papa wrestled. He knows that his Pop, who is Blackjack, wrestled, and that Barry and Taylor wrestle,” Windham said about his son, Knash. “So he thinks that everybody is a wrestler.”

Neither Windham nor Taylor was ever far from Mike, their lifelong example of “what men do,” after they received their respective summonings up to WWE’s main roster. There, they were finally able to interact professionally with their father, who worked with WWE until 2020.

“A lot of guys that have the athletic ability and the ability to hurt people like my dad does don’t use that power in the right way,” said Taylor. “He is one of the most respected and well-liked people backstage and throughout the industry that you could ever want to be. He has the ability to kill you, but he has the professionalism in him that is unparalleled.”

Even after the Rotunda boys joined their father in WWE, they still had the full slate of small-town experiences that forged their characters.

“I tell stories in the locker room of my childhood and the crazy things that happened throughout it, and people from all over the world cannot believe it,” Taylor said. “The life we lived, even though it was in a small town, it was quite crazy. And the characters and the people that we have had in our life since a very young age, regardless of however many other people that I have met, have consistently stayed the craziest and wildest people that I have ever met.”

In Windham’s case, the transition from the unremarkable Husky Harris—a big boy, to be sure, but one young talent among many in the early days of NXT—to the unforgettable Bray Wyatt came with a rebranding that had some small-town flavoring.

“Where my name came from, actually, my wrestling name—it came from a friend of mine that I grew up with,” Windham said. “That was just a hard-edged, tough dude. Dusty Rhodes asked me, ‘Who was the craziest person you grew up with?’ And I said, ‘A couple of people! Everyone is crazy where I grew up!’ But I said, ‘I knew this guy Bray who went through a windshield and didn’t have full feeling in his face, and he was nuts, but in a good way.’ And when we explain these characters to people, they think we are being ridiculous or telling tall tales. But [Brooksville] is a special and unique place.”

So the meat of the wrestling lifestyle came from Dad, and the seasoning came from Brooksville. But what about Mom? Windham credited Blackjack Mulligan’s only daughter—a free spirit with an often-absent father—as the most dependable person in his life. And he further insisted that she was a driving and motivating force that encouraged him to be the best possible parent he could be.

“That was her, always,” Windham said. “She is such a humongous part of my personality and who I am as an eccentric person. She molded the most of me. They both did. They both were such solid people in their own way. … I love wrestling, and it has been good to all of us, molded every aspect of our lives. But it is not where it begins and ends. It is just a beautiful piece of our story.”

Reflecting on his son’s legacy, Mike sought to capture Windham’s essence as both a public figure and a beloved family member. “Windham was a special person who will be missed by millions of people, and especially by his family. Most of all, as parents, my wife and I—and the rest of our family—are most proud that he was kind and generous, including to people he didn’t even know. People were naturally drawn to Windham starting from when he was a child.”

In a community where larger-than-life characters often overshadow the person behind the persona, Windham Rotunda’s humanity, kindness, and generosity stand as a testament to a life lived fully, both inside the ring and out.

Ian Douglass is a journalist and historian who is originally from Southfield, Michigan. He is the coauthor of several pro wrestling autobiographies, and is the author of Bahamian Rhapsody, a book about the history of professional wrestling in the Bahamas, which is available on Amazon. You can follow him on Twitter (@Streamglass) and read more of his work at iandouglass.net.

Oliver Lee Bateman is a journalist and sports historian who lives in Pittsburgh. You can follow him on Twitter (@MoustacheClubUS) and read more of his work at oliverbateman.com.