If you’re a Star Wars fan, then at some point—maybe many points—you’ve pretended to be a Jedi. Most of us don’t get caught on camera, but that doesn’t mean we don’t try and fail to Force push and pull in the privacy of our homes. Even people who’ve played Jedi on-screen can’t resist real-life Force fantasies: Hayden Christensen made lightsaber sounds on set, and Ewan McGregor pretends to use the Force to mind-trick his kids and to open doors at the supermarket. What would a Jedi be without the Force-power perks?

Ahsoka is asking that question—one that its creator, writer, and sometime director, Dave Filoni, gave voice to earlier this year, while promoting The Mandalorian. “The interesting question is how you define when someone is a Jedi,” Filoni said. “That’s the real question, because the Jedi is a way of training. It’s a way of philosophy and being.” That’s a radical reframing of how most Star Wars projects present the Jedi order—but it’s also, unbeknownst to many Star Wars fans, one with roots that extend to George Lucas’s original vision of how his galaxy would work, as well as to many prior stories, canonical and not.

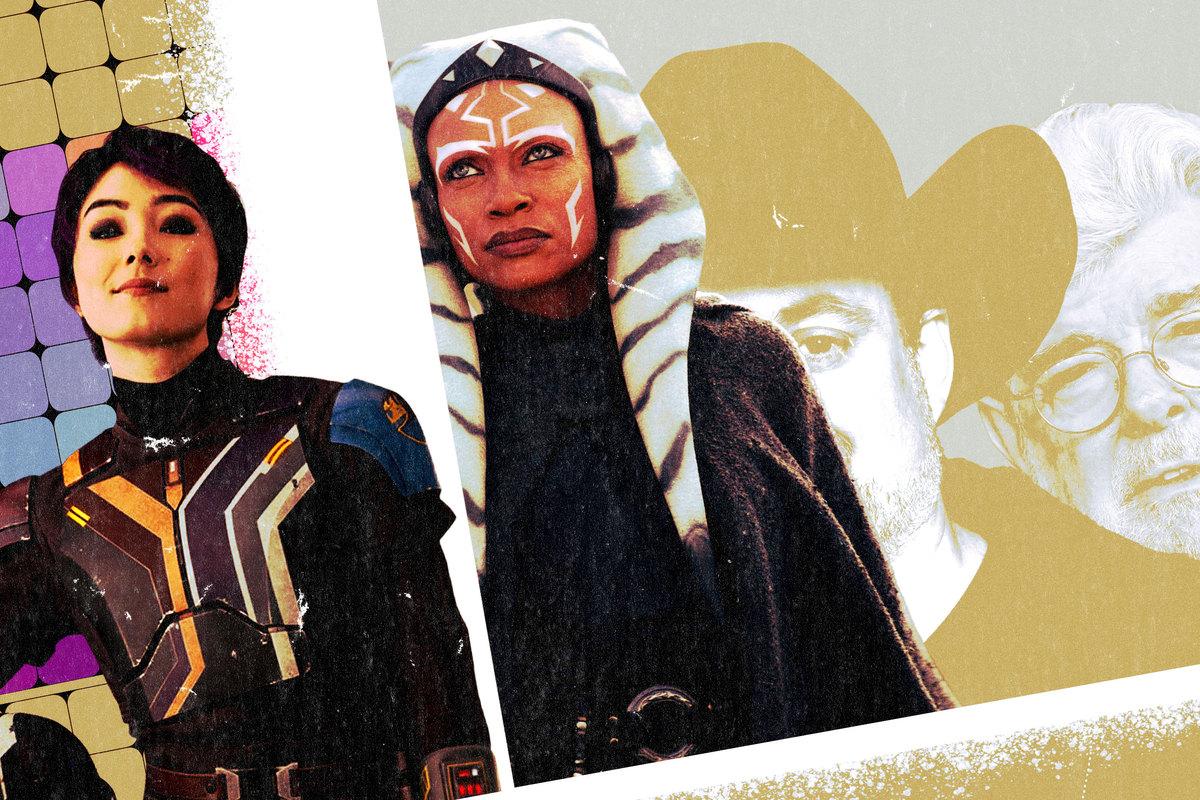

Compared to mostly Force-free films and series such as Rogue One, Resistance, Andor, or The Bad Batch, Ahsoka evinces a conventional fondness for Force powers. On this show, you can’t swing a lightsaber without hitting someone else’s; the two-part premiere featured no fewer than six of the blazing blades. Whom those blades belong to is a lot less conventional: There isn’t a card-carrying, traditional Jedi in sight.

There’s Ahsoka Tano, the former Padawan who was expelled from the order during the Clone Wars on suspicion of sabotage, opted not to rejoin it after being cleared of the charge, and famously declared, “I am no Jedi” in Rebels Season 2. There’s Marrok, a former Imperial inquisitor, and Morgan Elsbeth, a former member of the Nightsisters of Dathomir. And then there’s Baylan Skoll, a former Jedi turned mercenary, and his apprentice Shin Hati; with their orange-red sabers, Hati’s Padawan braid, and Skoll’s expressed regret about the prospect of having to kill Ahsoka, the duo make darker but equally unclassifiable counterparts to the titular protagonist and her unorthodox apprentice, Sabine Wren.

Of those six Jedi-adjacent characters, Sabine is the least conventional lightsaber wielder of all. A Mandalorian of many talents, Sabine seems to lack the core prerequisite for Jedi training. “I can’t use the Force,” she says in the third episode. “I don’t feel it.” Yet despite her current inability to “see” with her eyes obscured or pull a cup across a table, Sabine is Ahsoka’s past and present Padawan. What gives?

In three respects, Ahsoka the character and Ahsoka the series are rebukes to Jedi dogma—both the in-universe order’s rigidity, and the IRL expectations and misconceptions about the Jedi instilled by the Skywalker saga. The first Force shibboleth is that standout skills tend to follow famous families; like The Last Jedi’s emphasis on “Broom Boy” and on Kylo Ren’s revelation that Rey’s parents “were nobody,” Ahsoka suggests that characters who don’t belong to a lineage of villains or heroes have a prominent “place in this story”—that you’re not nothing just because you come from nothing. Second, Ahsoka challenges the dark side/light side binary predicated on the belief that there are strictly delineated evil and virtuous ways to use the Force. Ahsoka herself is something of a Gray Jedi who sees the Force as a spectrum; after a fashion, perhaps, so are Skoll and Shin, whose Norse-inspired lupine names (a Filoni trademark) speak to their amorphous morals—as Huyang would say, “Not bad. But not good.”

Admittedly, they may be mostly bad, and Ahsoka may be mostly good. Despite her scorn for “standard Jedi protocol,” Ahsoka has mostly acted in ways that wouldn’t have fazed the stodgy masters (and droids) of her old order. However, she has departed from their typical practices in one extremely noteworthy way, which brings us to the third and maybe most revolutionary view advanced by Ahsoka: the idea that Jedi training doesn’t depend on having a high midi-chlorian count. Can someone like Sabine really learn to internalize the precepts of the order without a feel for the Force? Not from a Jedi, probably. But Ahsoka is something else.

Obviously, Sabine isn’t separate from the Force. As Ahsoka reassures her pupil, “The Force resides in all living things.” Her words, identical to Kanan Jarrus’s in Rebels and almost identical to Yoda’s in The Clone Wars, also echo Obi-Wan’s to Luke, about how the Force is “an energy field created by all living things,” one that “surrounds us and penetrates us.” Or Yoda’s to Luke, about how “life creates it, makes it grow.” Or Luke’s to Rey, about how “it’s the energy between all things, a tension, a balance that binds the universe together.” Or Kanan’s to Ezra Bridger: “You’re connected to every living thing in the universe.” Or—well, we could go on.

Still, it’s one thing to be connected to the Force, and another entirely to be able to detect and leverage that connection. Or is it?

Not to hear George Lucas tell it—or, at least, not to hear how he told it decades ago. While making Episode IV, Lucas said, “The Force is really a way of feeling; it’s a way of being with life. … The Force is a perception of the reality that exists around us. You have to come to learn it. It’s not something you just get. It takes many, many years. … The Force is always there, however. Anyone who studied and worked hard could learn it.”

During production of Return of the Jedi, Lucas doubled down. “Everybody can do it,” he said of using the Force, adding, “It’s just the Jedi who take the time to do it.” Using the Force, he continued, is “like yoga. If you want to take the time to do it, you can do it; but the ones that really want to do it are the ones who are into that kind of thing.”

Granted, right after that latter quote, Lucas also said Yoda “doesn’t go out and fight anybody” and implied that the diminutive master wouldn’t hold his own against a Sith lord. Clearly, that changed. But Lucas has been quite consistent on the question of Force use. As he said years later, “Everyone has the Force in them.” Other oft-recirculated quotes declare that “every [living] being has the Force,” and that “it’s something you can learn to use.” Even varied levels of midi-chlorians—a prequel-era concept Lucas views as consistent with his original, populist stance on the Force—don’t preclude the development of Force sensitivity. In The Phantom Menace, Qui-Gon Jinn tells Anakin that midi-chlorians reside in “all living cells”—not just those of the Jedi. That jibes with Lucas’s insistence that Jedi knights’ midi-chlorian counts don’t make them superheroes: “We all have midi-chlorians. We all have the Force within us. We can all do what the Jedi can do, but we’re not trained.”

Lucas’s quotes aren’t canon, but Filoni learned at Lucas’s knee, and he undoubtedly knows (and wants to honor) how his mentor feels about the Force. Hence the positioning of Sabine as a street-level Jedi hero. Nothing about Sabine’s training runs counter to the essence of Star Wars, as conceived by its creator or described by Lucas either on- or off-screen.

Which isn’t to say that her road won’t be bumpy. The Force, Qui-Gon explains in The Clone Wars, is bipartite: The Living Force generated by all living beings powers the Cosmic Force, “binding everything and communicating to us through the midi-chlorians.” Lucas was clear that “the more midi-chlorians we have, the more accessibility we have to the Force,” and that “the Jedi, by nature of their genetics, have more midi-chlorians than most people.” As Ahsoka concedes in this week’s episode, “Time to Fly,” “Talent is a factor.” Most Jedi recruits demonstrate some natural aptitude for Force use when they’re young, without practice or instruction; Ahsoka distinguished herself as Jedi material when she was a baby.

But Ahsoka also says that “training and focus are what truly define someone’s success,” which makes the Jedi sound closer to the rigorously trained Bene Gesserit from Dune than the supernatural Maiar from Lord of the Rings. That’s consistent with some sentiments expressed in previous Star Wars stories. “When you learn to quiet your mind,” Qui-Gon tells Anakin in Episode I, “you will hear them speaking to you.” Similarly, Kanan informs Ezra that to be a Jedi, “You have to let your guard down. You have to be willing to attach to others. … If you hang on to your past, if you always try to protect yourself, you’ll never be a Jedi.” Kanan also tells Hera Syndulla that Sabine is blocked—her mind is conflicted. “You’re training the body, but you must also open your mind,” Ahsoka says in Episode 3. “Learning to wield the Force takes a deeper commitment.”

Sabine probably isn’t like Luke Skywalker, Ahsoka, Cal Kestis, or other naturally gifted Jedi who temporarily became cut off from the Force, or cut themselves off. She’s not intentionally hiding her light side under a bushel. But even Jedi masters found their powers diminished when Darth Sidious ascended and the Force was clouded with darkness and pain. Sabine’s been at war for much of her life, so long that she’s seemingly unprepared for peace. She’s lost touch with herself, as she’s lost touch with Ezra—whom her training may make her feel closer to. But with the right mindset and the proper approach, she could harness whatever potential her presumably meager midi-chlorian count allows. And maybe midi-chlorians are like muscles, growing stronger with hard use.

Ahsoka’s portrayal of Sabine’s Jedi journey could help humanize the franchise’s space wizards and witches, nudging the prevailing understanding of the Force from one where only midi-chlorians determine a Jedi’s destiny to one more in line with Lucas’s less elitist and more democratic, nuanced notion. However, the series still has a lot to explain. It’s not yet apparent why Sabine, who’s highly capable without Force powers, wants to be a Jedi. Nor is it clear what she can accomplish, in practical terms. Because canon and Legends alike are in lockstep about one thing: Although the door to the Force isn’t completely closed to anyone, a lack of natural talent lowers one’s skill ceiling significantly.

A short-story anthology published last year, Stories of Jedi and Sith, contains the clearest canonical depiction of what the Jedi path looks like for midi-chlorian normies. In Michael Kogge’s “What a Jedi Makes” (Yoda-speak for “What Makes a Jedi”), which is set during the High Republic era, a 14-year-old Jedi superfan from Coruscant’s lower levels, Lohim Nara, travels to the Temple to be trained. Although he knows he’s not gifted, he cosplays as a Padawan, wearing pilfered robes, carrying a lightsaber constructed from a welding torch, and brandishing a blood test with faked midi-chlorian counts.

“Midi-chlorians,” Yoda responds, after the ruse is revealed. “You think midi-chlorians are what make a Jedi?”

“No,” Nara answers. “The Force is what makes a Jedi. And that’s the one thing I don’t have.”

Yoda asks him what he means. “I can’t call on it,” Nara replies. “Not like you. … I can’t summon a lightsaber to my hand without trickery. I can’t read people’s minds. I can’t feel it, the Force, at all. I’m just ordinary.”

Yoda, disappointed as he would be by Luke’s lack of faith, says, “Then never a Jedi you will be, if that is what you believe.”

Nara, sensing an opening, asks if there’s a way that he can be a Jedi. Yoda tells him to study Lyr Farseeker, who had “no great power” but nonetheless wrote “some of the Jedi’s greatest texts” (including one from Luke’s library that Rey salvages from a fire in The Last Jedi). “For though the Jedi and the Force are one,” Yoda concludes, “the Force is not what a Jedi makes.” That, he says, “is something only you can answer.”

When an initiate notes that Nara is too old to train to be a knight, Yoda says, “Over 600 years of age am I, and still a student.” He also observes that the Jedi aren’t just a fighting force: “More than knights the Jedi order is. Watchers. Stewards. Caregivers, also. Of these flowers. The grounds. Our home. A guardian of the Temple you can be if ready are you.” Nara’s in the building, but it’s a qualified empowerment. Basically, he gets to be a groundskeeper, or a Jedi janitor. Honorable work, but not quite the stuff Force fantasies are made of.

In Legends tales, there were weak Padawans, such as Scout and Zayne Carrick, considered fringy Jedi prospects at best. To avoid washing out of the order, they had to work harder than everyone else. There were also other scholars like Lyr, most notably Tionne Solusar. In both canon and Legends, younglings who didn’t make Padawan and Padawans who never made knight could be reassigned to the Jedi Service Corps—specifically, the Agricultural Corps, the Medical Corps, the Educational Corps, or the Exploration Corps. But it doesn’t seem like Sabine aspires to be the next Lyr, Solusar, or Jedi librarian Jocasta Nu, or to join the Jedi equivalents of the Peace Corps, Habitat for Humanity, Doctors Without Borders, or Teach for America.

Sabine’s skills with weaponry alone, Ahsoka says, “will not be enough to defeat our enemy,” which could imply that the purpose of her training is to develop a more potent, Force-based suite of skills. If so, that seems like a long shot in the short term, considering Sabine can’t move a mug. But as Ahsoka says, “I don’t need Sabine to be a Jedi. I need her to be herself.” Maybe making Sabine a Padawan is a way of helping her clear her mind so that she can reach the rest of her potential. In other words, it’s not about bringing balance to the Force, but about bringing balance to Sabine. The sort of balance and serenity that, say, Chirrut Îmwe had when he knew he was one with the Force and the Force was with him.

In The Last Jedi, Luke asks Rey what she knows about the Force. “It’s a power that Jedi have that lets them control people and make things float,” she replies, to which Luke responds, “Impressive. Every word in that sentence was wrong.” It’s not just Jedi who have that power, or even other Force religions like the Matukai or Chirrut’s Guardians of the Whills. No one really possesses that power, which flows from the Force, but in theory, anyone can sense it, of which Luke is well aware. In the third issue of the Marvel comic The Rise of Kylo Ren, Luke tells one of his weaker Padawans, “The Force can be a trickle, a stream, a river, a flood … for anyone who can sense it. Think of yourself as a door. The wider you open, the more easily the Force flows through you. Some people just start out with their door a bit more open. But any door can open wide.”

Ahsoka still has to make the case for why Sabine has set her sights on being a Jedi, but there’s plenty of precedent that shows she can be, from a certain point of view. No, she probably won’t ever master the skills Star Wars fans dream about—the kind that captivate us as kids and make Jedi seem so wizard in the first place. (Though she may learn to talk to the whales.) But there’s more to her training than that.

In some respects, Ahsoka is still searching for its footing. But through three episodes, the series has already shown us that there’s more than one Star Wars galaxy, and reminded us that there’s more than one way to relate to the Force. So if Sabine’s apprenticeship makes you think, “That’s not how the Force works,” you must unlearn what you have learned. As Ahsoka said in the second season of Rebels, “In my experience, just when you think you understand the Force, you find out how little you actually know.”