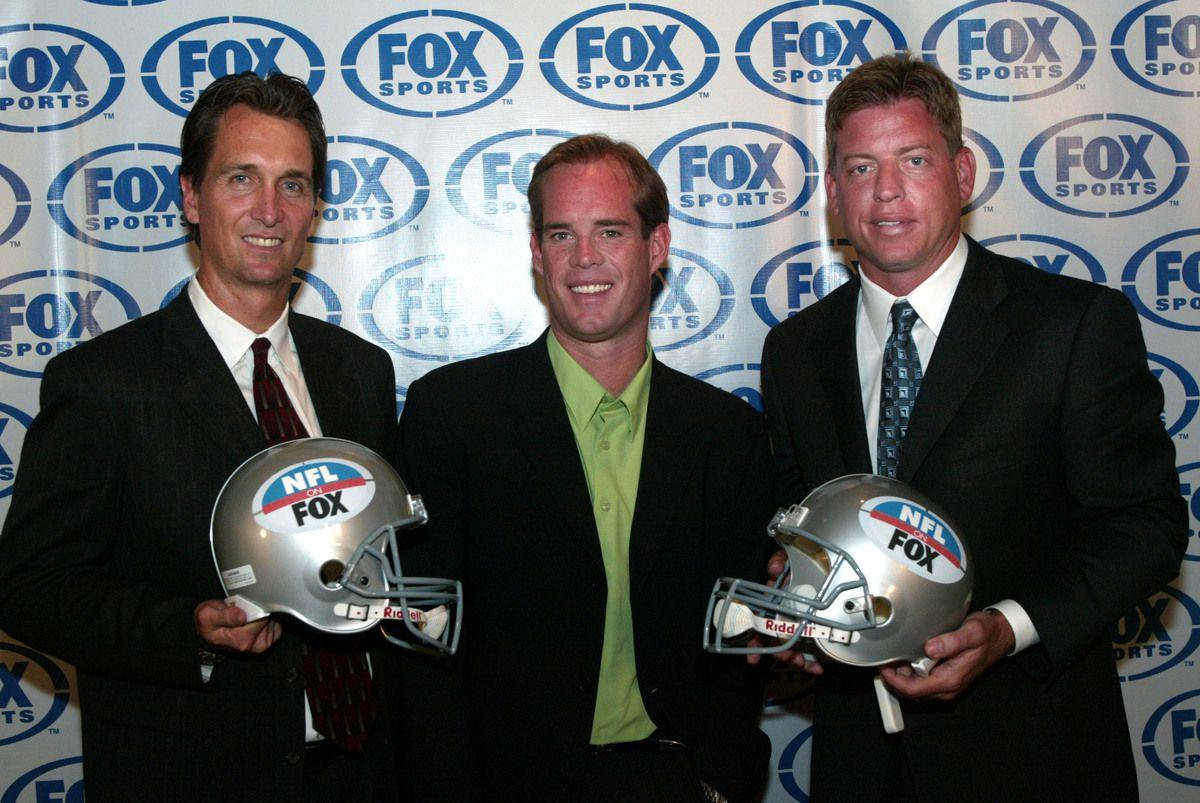

22 Years of Joe Buck and Troy Aikman

With this NFL season being their 22nd in the booth together, Joe Buck and Troy Aikman will surpass John Madden and Pat Summerall as the longest-tenured NFL announcing pairTroy Aikman has a story about his partner, Joe Buck. It happened in 2011, the week before Buck and Aikman called a snowbound Super Bowl XLV in Arlington. “There’s no one on the roads,” Aikman said in a Washington, D.C., hotel last month. “We’re driving along. I don’t even know if Joe remembers this.”

“I have no idea,” said Buck, who was sitting nearby.

“Joe says something to me,” Aikman continued. “He says, ‘God, what if we fuck this game up?’”

By 2011, Buck and Aikman had been announcing Fox’s “A” NFL game for nearly a decade. Though they were well-known to viewers and admired by their bosses, Buck sometimes got stuck in his own head.

In Texas, Aikman tried to yank him out of it. “Are you kidding?” he told Buck. “We’ve been doing this for 10 years. On our worst day, we haven’t fucked it up.”

“Let me tell you something,” said Buck, as if he’d received his partner’s pep talk intravenously. “I’m not planning on having my worst fucking day, OK?”

At the end of this season of Monday Night Football, Buck and Aikman will have been ribbing each other for 22 years. That’s a significant number. It means they will have been partners longer than Pat Summerall and John Madden.

If it seems unthinkable that Joe and Troy could outlast Pat and John, consider the following: In 2002, when Buck and Aikman started calling games together, the second Iraq War hadn’t yet begun. The freshest piece of Star Wars content was Attack of the Clones. NBC was still making new episodes of Friends. At year’s end, Aikman will have stood next to Buck in the booth a full decade longer than he stood under center for the Dallas Cowboys.

How announcing partners feel about each other is a tricky thing to get a handle on. In Monday Night’s early years, Howard Cosell and Don Meredith were at each other’s throats. More often, announcers give us a contrived, made-for-TV friendship—one in which (the announcer swears) they “complete each other’s sentences” and that their partner is “the best in the business.”

Buck and Aikman became actual, non-TV friends. “We had a lot in common,” said Aikman.

“I was a great athlete, he was a great athlete,” said Buck.

Even before last year, when ESPN reportedly paid them a combined $34 million a year to rescue Monday Night Football, they were in the midst of a critical renaissance. There’s the sheer length of their tenure: Buck and Aikman have been together a decade and a half longer than any top network NFL team. It’s worth studying a 22-year relationship: Joe and Troy’s with each other, and ours with Joe and Troy.

Before they outlasted Summerall and Madden, Buck and Aikman replaced them. At Super Bowl XXXVI in 2002, Summerall and Madden said goodbye to each other: Summerall because he was running out of gas, and Madden—not for the first time—because he had options. Aikman became close with Madden when Madden covered Cowboys games during the ’90s. Madden called Aikman to say, “I’m leaving Fox and I’m going to Monday Night Football.”

For viewers, the breakup of Summerall and Madden was an emotional event, like the end of a beloved TV series. Fox faced the tricky problem of picking their replacements. Ironically, executives turned to the same playbook they’d use two decades later when Buck and Aikman left for ESPN: Bring in the fresh faces!

Buck, who was 33, was Fox’s young star, having already called four World Series. Aikman, who was 35 and a year removed from the playing field, had impressed his bosses when he stepped into the analyst’s seat that Matt Millen vacated to run the Detroit Lions. “Troy had been to the Madden University,” said David Hill, the former president of Fox Sports. “John thought the absolute world of Troy.”

Hill had a fondness for three-man booths. And he didn’t want two announcers to bear the weight of replacing legends. So he chose Cris Collinsworth, who had a decade’s worth of TV experience, to be a co-analyst with Aikman.

“Was he thrown into the deep end?” Hill said of Aikman. “Absolutely. But Cris gave him a pair of floaties for a while.”

In 2002, Buck and Aikman didn’t have enough stature in the business to get to choose to work with each other. They’d met only once. As the Cowboys dynasty crumbled in the late 1990s, Aikman poured his heart out to Madden during pregame production meetings. “He basically became my therapist,” said Aikman.

One week, Fox assigned Buck, who got the network’s less glamorous assignments, to call a Cowboys game. Madden’s absence was a bummer for Aikman and, by extension, the dynasty. “That had to have been the moment he knew it was over,” said Buck.

The Buck-Aikman-Collinsworth booth—now all but lost to TV history—sounded good. But Aikman and Collinsworth were job sharing. In 2005, after calling the first Patriots-Eagles Super Bowl, Collinsworth left Fox for NBC. Buck began that fall’s season opener by saying, “I’m Joe Buck along with”—he looked left as if checking to see who was next to him—“Troy Aikman.” Buck and Aikman were now a duo. They were aligned.

TV conspires against announcing partners becoming close friends. Even if they like each other—hardly a guarantee—they must navigate dueling professional ambitions, a finite amount of airtime, and the fact that one might tap out before the other. Summerall and Madden, a perfect on-air team, didn’t hang out.

At first, Buck and Aikman remember being almost intimidated by each other. In Washington, Buck said it was something about Aikman’s presence, his Hall of Fame résumé.

“It’s interesting to hear him say that,” said Aikman. “Obviously, we’ve not talked about that, but I felt the same way.” For Aikman, it was how smooth Buck was on the mic, how young he was compared to the father-figure announcers Aikman was used to.

Largely by happenstance, Buck and Aikman were the kind of people cut out to become friends in adulthood. They were close in age. Each man had daughters. “We went through our divorces at roughly the same time,” said Aikman.

During their freshly divorced period, in the early 2010s, they began taking trips together in the offseason. They went to Mexico, Florida, California. They played lots of golf. Their game calls glowed with conviviality. Buck would make a point and Aikman would say, “You’re absolutely right, Joe!”

If Buck and Aikman ever had a major falling-out, the kind of misalignment so many partners suffer from, their Fox crew never saw evidence of it. “The comment I get most is ‘It sounds like you and Troy like each other,’” said Buck. “It’s like, yeah, we do. Maybe that’s weird, but we do.”

Of the two, Buck is the one who’s prone to making emotional declarations of friendship. He regrets that a 2006 baseball assignment in Los Angeles kept him from attending Aikman’s induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. “That kills me that I wasn’t there for that,” he said. “I was sitting there watching in my hotel room, emotional.”

“Bullshit,” Aikman said with a smile.

“It’s true,” Buck protested. “I swear to God.”

“He was golfing at Bel-Air,” said Aikman. “What are you talking about?”

The night after I saw them at the hotel, Buck and Aikman stood in the booth at FedEx Field to call a Commanders-Ravens preseason game. They had taken up the same positions they have for 22 years: Buck to the left, Aikman to the right. When the game began, they powered through a bag of old-fashioned yellow Halls cough drops. They suck on them as a kind of shared nervous tic, something to do while calling a game. Buck can place a cough drop in his bottom lip in such a way that people at home are none the wiser.

Buck and Aikman hardly look at each other during games. Like a lot of announcers, they’ve developed a system of nonverbal signals. Buck can tell Aikman wants to talk when he feels him lean forward, like he’s waiting for a snap from his old center Mark Stepnoski. Aikman can tell Buck wants him to talk when Buck turns to face him instead of the field. During these exchanges, they gesture with their hands, like they’re making a silent movie about announcers.

Getting along with your partner is not an end in itself. Announcers who hate each other’s guts have made good TV. Where Buck and Aikman’s friendship is interesting to football fans is in the way their personalities fit together on the air.

Since the dawn of the medium, most booths have had one announcer who slides into the role of the star, the volume shooter. That was Madden, mooning over a sloppy-bodied lineman. The other announcer becomes his sidekick. That was Summerall, guiding viewers back to the action on the field with a concise, flinty remark.

Neither Buck nor Aikman was cut out to be the on-air star. In the 2010s, Buck went through a period when he could call a game like nobody’s business but was wary of revealing too much of his personality. Aikman told me what worried him about doing TV was that it would require him to talk wall-to-wall for three hours.

“This is Troy’s show,” Buck said deferentially.

I asked Aikman whether he agreed with that.

“I don’t feel that way at all,” he said. He smiled again. “And at the end of the day, I don’t think Joe feels that way, either.”

“I knew he was going to say that,” said Buck.

This no-after-you dynamic gives Buck and Aikman’s broadcasts a distinct sound. Sometimes, Buck will call a play and Aikman will say … nothing, because Buck doesn’t make him feel like he has to—and, crucially, Buck isn’t chewing scenery in a way that makes Aikman’s silence stand out. Neither man feels like they’re lunging for the microphone in a type-A, announcer-y kind of way.

This style is harder to explain than Madden’s riffing or Collinsworth breaking down a replay out of a commercial break. That, combined with the modesty of Buck and Aikman’s longtime Fox producer, Richie Zyontz, made Joe and Troy—at least for a time—fairly underrated. Of the idea that he and Buck would create a collective wall of sound, Aikman said, “I don’t want to listen to that as a viewer.”

Buck and Aikman are built very differently. What Buck admires about Aikman is how screwed on he seems to be as a person. Aikman prepares for calling a game the same way every week; he comes into morning production meetings drenched in sweat from a workout while Buck is still waking up.

Aikman was criticized early in his career for not offering big takes. The Fox crew came to realize that what Aikman valued as an announcer was honesty, steadiness. “He’s consistent,” said Buck. Combine that with Tony Romo’s spasmodic brilliance in the booth and you realize a truth about announcers: They are who they were as players.

As a Cowboys quarterback, Aikman became hardened to a lot of the criticism he got from the peanut gallery. He found it amusing that, for a time, Buck was worried about his Twitter mentions. God, what if we fuck this game up?

After games, when they hopped in a car to go to the airport, Aikman would steer Buck into the front seat. “Which I’m not comfortable in,” said Buck. From the back, Aikman would read tweets aloud—“Hey, Joe, what about this one?”—until Buck begged him, “Would you please stop reading those?”

What Aikman admires about Buck is that he doesn’t seem screwed on so tightly. “Joe has a levity and a looseness to him,” he said. In the booth before a big game, Buck would sing “Ring of Fire.” Or he’d take the yellow legal pad the late Tim McCarver used to carefully script out his opening spiel and write “Give ’em the finger.”

If you spend time around them, you discover something that doesn’t come through on TV. Aikman thinks Buck is incredibly funny. There can’t be that many people on the planet who think Buck is funnier. (I’ve found Jimmy Johnson feels the same way about the comic stylings of Terry Bradshaw.) Last season, during rehearsal before a Buccaneers-Saints game, Buck juiced up his pregame introduction to Musburgerian levels. Aikman laughed. So when the telecast began, Buck juiced up his intro even further, so much so that viewers wondered whether he was drunk.

“What he said about me as far as being disciplined, driven—all those things are true,” said Aikman. “My intensity runs pretty hot, and I’ve got to pull off of that a little bit. I think I have. I think I’m better now than I was. There’s a lot of reasons for that. But Joe’s a part of that. Joe’s helping me with that, as well.”

There’s no Next Gen Stat to measure how good announcers are. Public reevaluations can come at odd times. In 2016, Buck published a memoir in which he wrote about his hair plugs, his relationship with his announcer dad, Jack, and the courting of his second wife, ESPN reporter Michelle Beisner-Buck. This confessional process, still ongoing, helped viewers match a human to a voice.

Aikman’s reevaluation was more subtle, and it happened almost entirely on TV. In 2018, he and Buck started calling Thursday Night Football games for Fox in addition to Sunday games. Having two games per week to cram for—along with Buck’s baseball duties—made them just call the game and not worry about overpreparing.

A lot of Fox’s Thursday matchups were pretty lousy. “People aren’t as interested in the game or what’s happening on the field, for the most part,” said Aikman. “So it allowed me to go to different areas, do it a little bit differently, have a little more fun—and us together to have more fun.”

Another factor favored Aikman, too. Network NFL announcers got nicer over the last 20 years, less likely to lay into players and coaches than they were in the lower-your-helmet ’90s. Aikman’s steadiness makes him sound more honest than a lot of his colleagues.

In 2021, Aikman had a clause in his contract that allowed him to search for offers from networks other than Fox. For a time, Buck thought Aikman might split his duties between Fox and Amazon. At a private dinner before the NFC championship game in 2022, Aikman told Buck he thought he might be finished at Fox entirely. Then Aikman thought he was going to Amazon, though a few weeks later ESPN hired him for a reported $19 million a year.

Buck and Aikman were now big enough that they could choose their partners. “If I didn’t want to continue to work with Joe,” said Aikman, “I could have very easily said to ESPN, ‘Hey, look, Joe’s great, but let’s go a different route. I think it’s probably time or whatever.’ There were some other people that were interested in the job, of course. And Joe could very easily have said to Fox that he was going to stay.”

Buck hardly needed Aikman to recruit him to go to ESPN. Beisner-Buck already worked as a reporter on Monday Night Countdown. The money was going to be great. A phone call with his old boss David Hill, who argued that a new challenge was good for him, helped put him over the top.

“It was just kind of understood that if I can, I will,” said Buck. “And if they don’t let me out, I won’t.” He still had a year left on his deal at Fox.

“My worry was that a lot can happen in a year,” said Aikman. “Not that I didn’t think that’s what he wanted. But a lot can happen, and then it could be like, ‘Hey, I know I said I was coming, but …’”

After Fox let Buck out of his contract, he called Aikman to tell him the news. “He was like a little kid when I called him,” said Buck. “Because he stresses about a lot of this stuff.” Both men signed five-year contracts that will expire after they call the Super Bowl in 2027.

It’s one last way that Buck and Aikman have come to resemble the announcing team they’re now outlasting. Back in 1994, Fox’s new sports division gained a certain stature from the TV magic that Madden and Summerall had created at CBS. With Buck and Aikman, ESPN is attempting a similar organ transplant. ESPN wants to go from a network whose relations with the NFL were so dismal that an executive publicly lobbied for a “reset,” to one that will show the first Super Bowl in its history three seasons from now.

What ESPN was buying isn’t just Buck and Aikman’s call of the game. It’s the qualities of a partnership that even their new bosses may be unable to describe. The price tag was a mere $170 million. So far, Buck hasn’t needed any pep talks.