In 1980, the Las Vegas Sun reported on an especially visible marital dispute. A fight had taken place on the front lawn of a modern mansion that all the neighbors knew about. Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal and Geri McGee Rosenthal were not just rich, but also notorious; wherever the couple went, dark, momentous forces followed. Over 10 years later, veteran crime writer Nicholas Pileggi—fresh off Goodfellas, his lucrative collaboration with Martin Scorsese—shared the news clipping with the famous filmmaker. In the scene described in the article, there was a whole epic text: a damaged car, an appearance by the FBI, and 10 years of prelude involving the great shining prosperity of organized crime networks from multiple regions. Murder, robbery, gambling, and glamour—underneath it all Scorsese saw the entire American mythos.

The American 20th century has long been Scorsese’s cinematic sandbox. For roughly the first decade of his career, he played in it by making intimate, small-scale character dramas featuring fictional people whose lives were unmistakably forged by larger historical forces like the Vietnam War (Taxi Driver), the Great Depression (Boxcar Bertha), and the ever-present shadow of Catholicism (Who’s That Knocking at My Door). In 1980, Raging Bull became his first adaptation of a real American’s life in boxer Jake LaMotta. Over the following decade, he made a dark farce about the lust for television fame (The King of Comedy), an entry in the yuppie nightmare cycle (After Hours), a Jesus epic (The Last Temptation of Christ), and a pool shark drama (The Color of Money) before landing on the American subject, and way of portraying it, that most know him for. Goodfellas moved Scorsese’s focus to people who were themselves forces of history, not its imagined victims. He had shown us petty, ineffectual young criminals from this Italian New Yorker world before in 1973’s coming-of-age tragedy Mean Streets—but here was a much more potent, hardened, real breed of gangster. In chronicling them, he established the movie language that would define him, marked by frequent scene hopping, navigated by voice-overs, and guided by an active camera through intoxicating and nefarious settings as Motown ballads and blues riffs emanate from the rooms the viewer is whisked so thrillingly through.

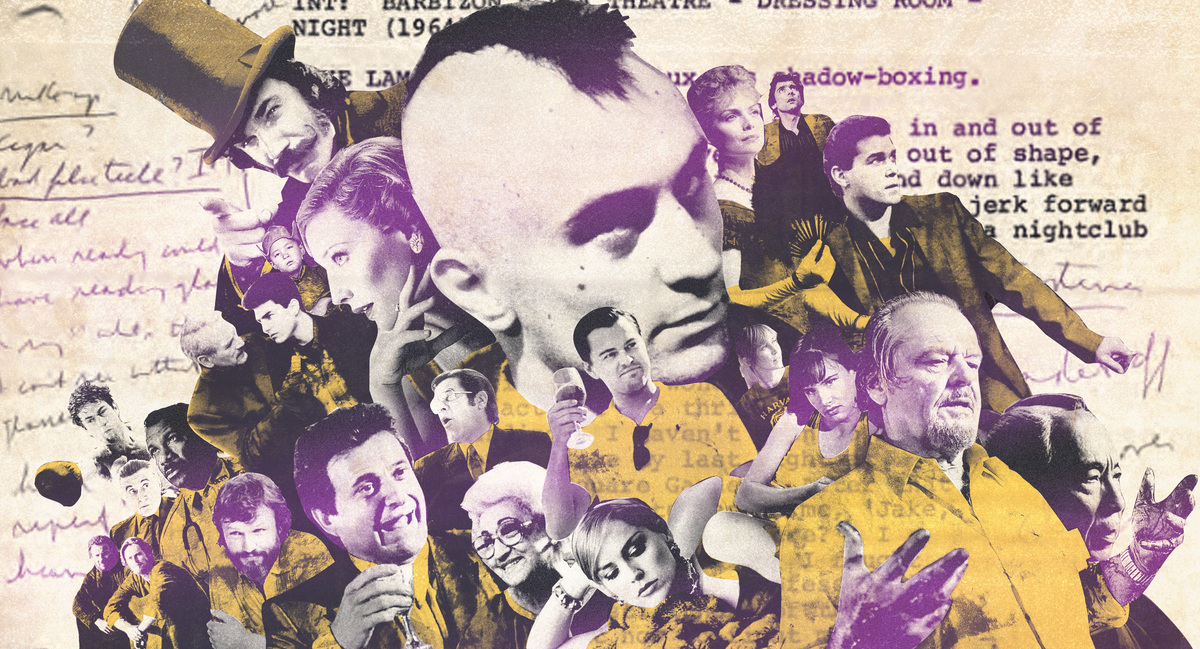

Stimulating, compelling, and warm, Scorsese’s stream-of-consciousness approach to true crime created a whole new movie modality. It has consistently transcended genre—or, to many, become a genre—and with each installation of his signature style, Scorsese’s revelations about the roaming avarice of the American experiment have grown more stirring. With Goodfellas and the three subsequent films to utilize its spectacular confessional mode—Casino, The Wolf of Wall Street, and The Irishman—Scorsese has found his place as more than just an exceptional filmmaker and become one of America’s great moral voices.

This manner of moviemaking all started because Scorsese read Pileggi’s 1985 nonfiction book, Wiseguy: Life in a Mafia Family. A career crime journalist, Pileggi was approached by a then-in-witness-protection Henry Hill, who had already cooperated with the FBI and gotten his enemies locked up—he wasn’t too stingy with his stories, and Pileggi was more than ready for his frankness. “I had gotten bored,” Pileggi wrote in the beginning of the book, “with the egomaniacal ravings of illiterate hoods masquerading as benevolent godfathers.” Humbled and stifled by the milquetoast ways of his new life, Hill was a rambling interviewee whom Pileggi quotes for pages at a time. Pileggi always reasserts his own voice to frame and anchor these monologues, but readers might forget that the loquacious Hill isn’t the book’s official author.

Hill was essential to Pileggi’s book, but also to Scorsese’s production, for which he consulted heavily on matters of authenticity and style. Robert De Niro in particular leaned on Hill: “He was on the phone constantly,” Hill said in a later documentary. “Seven, eight times a day. He wouldn’t leave his fucking trailer without talking to me twice. … I thought he was a fucking nutjob.” As Hill and others would have it, De Niro does not—and cannot—capture the true cravenness of Jimmy Burke (Conway in the movie), and the same goes for Joe Pesci’s take on Tommy DeSimone (DeVito in the movie). Memorialized in full accuracy, the everyday malice of Hill’s running mates would be closer to snuff film than narrative cinema; DeSimone, per one anecdote, always tried out every new firearm he purchased by killing a random stranger with it. Nonetheless, Goodfellas manages to trouble viewers by sweeping them up in its rags-to-riches romance, creating a level of complicity that some might not recognize until Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill starts talking directly into the camera at the end of the movie.

Others, meanwhile, might choose to ignore the full parable of Goodfellas entirely. They remember the rollicking affluence, the sudden class mobility of swaggering criminality, but not the undoing poison that turns out to be its key ingredient. Scorsese’s first true crime movie gave birth to a certain dilemma of cultural reception that’s trailed the rest of his work: When depicting evil, what responsibility does a filmmaker have to extricate the excitement from the harm? It’s a question that won’t go away because it has no real answer, and Scorsese has never given in to the pressure of it by going didactic. “He doesn’t want to point fingers and make moralistic judgments,” says Thelma Schoonmaker, his editor on nearly every movie, “because he doesn’t think people listen to them.” Instead, Scorsese’s burden, as he understands it, is to show us the mess that America has made in its constant wedding of prosperity and violence.

In Casino, the scale of the criminal economy expanded. The Goodfellas crew managed a few newspaper-making heists, but Pileggi and Scorsese’s second collaboration featured men more organized and mathematical about their crime who grabbed an outsize share of an entire industry out West. The movie is based on the exploits of the aforementioned Rosenthal (Sam “Ace” Rothstein in the movie, played by De Niro), a shrewd, crooked sports bettor from an early age in Chicago. His habit started with work familiar to anyone on the FanDuel grind: wonky, detail-oriented research about and analysis of athletes, coaches, teams, and referees. But his habit grew more profitable when he started bribing players into point-shaving, among other extralegal methods. Rothstein got involved with a notoriously murderous racketeer, Nicky Santoro (Tony “The Ant” Spilotro in real life, played by Pesci in the movie). Longtime neighbors and acquaintances in a network of mafiosos with roots going back to Al Capone, the two became close friends, and then business partners, when they both fled to Miami because the heat was on them back home in Chicago. From there, both went to Las Vegas and made for a powerful combo of sneaky brain and bloody brawn, running four casinos while Santoro recreationally robbed people on the side. Everything falls apart when the Chicago bosses figure out they’re not getting their share from the operation; Rothstein survives a car-bomb assassination attempt, while Santoro fails to escape a blunt-force walloping in an Illinois prairie. If the famous “Layla” death montage of Goodfellas was too aesthetically pleasing, Scorsese makes sure to dial up the spare, grim unpleasantness of Santoro’s fatal scene to undeniable volume.

With Casino, the mob’s blend of indelible mythology and ruthless barbarism was shown to be more than just a New York or even Chicago affair. Like all things American, it frontiered and colonized new land. The movie is, in its way, as much a Western as a gangster saga, showing how—despite decades of legislation and regulation—America was still ripe for a freshly illegal pioneer voyage. In 1970s Nevada, masters of urban felony could set up shop several states over and amplify their tyranny cowboy-style, with bright lights to draw in an untapped pool of victims and rubes. Especially if you had a wealth of vision and a dearth of guilt.

After Goodfellas and Casino, Scorsese retired his signature storytelling style for the next 18 years. Screenwriter Terence Winter finally convinced him to bring it back for The Wolf of Wall Street, which showed a similar synthesis of greed and pizzazz dominating in a terrain where the stakes were even higher. With his red-hot verbosity, lack of scruples, and knack for finding similarly shameless men, Jordan Belfort manipulated American citizens to the tune of roughly 200 million fraudulently earned dollars. One of the movie’s great achievements is extratextual: Taken in context with Goodfellas and Casino, Wolf convinced audiences that there is little difference in honor between blood-soaked gangsters and ascendant finance celebrities. Like Hill before him, Belfort himself is integral to the film that tells his story. While Scorsese ignored Belfort (whom he recently compared to Donald Trump), Leonardo DiCaprio spent untold hours with him so that he could better know his demagogic energy. Crowds are thrilled to know that Belfort, like Hill, exists, and to experience his journey on the screen, either in spite of or because of the horrors he has subjected society to.

Scorsese has dedicated much of his career to studying people on the edges of society who will try anything—including, most certainly, killing—to break through its barriers and onto the main stage, though his most known stories are about those who have achieved such a conquest and become legend itself. Unprincipled losers and Sisyphean strivers do not all stay that way; some become monstrous enough to make it beneath the spotlight and hold space there for as long as they can. Scorsese is unparalleled at showing them in that glow, briefly flourishing under it but eventually melting from the heat.

Although it contains no murder, Wolf was his most disgusting movie yet. The source material, Belfort’s memoir, is stunningly vulgar. After a brief, obligatorily reflective intro, Belfort lapses into a “satirical,” “ironic” voice for the bulk of 530 pages, written mostly from prison, where he was inspired by Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities to write his own story. It is as misogynistic as it gets, vindictive, entitled, and racist. It probably goes without saying that he’s not a reliable narrator, either—“the most unreliable narrator in history,” per Winter—and in his book, there is no seasoned journalist like Pileggi to check his bullshit. (The wolf still roves today, dodging restitution payments, getting knee-deep in cryptocurrency, boosting QAnon-adjacent conspiracy fare, and constantly sanitizing himself with a podcast and more books, all the while denying that he ever intended to rip anyone off. He was trying to “help build America,” Belfort says.) Belfort’s day-to-day level of deceit, his staggering end-of-the-century stock market imperialism, was somehow even more unvarnished than the bile of Cosa Nostra hoods from decades prior; they knew, at least, how to temporarily cloak their menace with schmaltzy decorum—the Catholicism helped—and how to censor their most lizard-brained sexual impulses. Belfort instead delights in them, speaking of women in the distinct register of ownership while also being too drugged out much of the time to even enunciate clearly. He is Scorsese’s most unpalatable real-life antihero, and by far his most controversial—because, at the same time, he is his most appealing. DiCaprio’s boyish charm makes the movie downright addictive—unsurprisingly, Wolf brought in Scorsese’s largest box office haul—as Scorsese fuses and blurs the aspirational nature of wealth with its more cautionary elements. The perceived ethics of the movie led to countless debates, made hotter by Belfort’s participation and the fact that the movie’s financing was tied up in a massive international money laundering scandal; one of its producers, Riza Aziz, was arrested in 2019. Belfort, dollar signs still in his eyes, tried to sue him for $300 million.

After Wolf, Scorsese put true crime down for another six years, releasing the 17th-century religious epic Silence in 2016, but he brought it back once again for The Irishman in 2019. Like any good Catholic, he remained obsessed with sin and reutilized the momentous, verbally relentless style of Goodfellas, Casino, and Wolf to visit one of America’s more infamous trespasses: the disappearance, and presumed murder, of labor leader Jimmy Hoffa. Here the narration is more solemn, though, and as such represents what the—again—extremely Catholic Scorsese has perhaps long been after: a confessional booth. Adapted from the book I Heard You Paint Houses, written by investigator Charles Brandt from the dying memories of the Irishman himself, Frank Sheeran, the movie immediately subverts the infamous combination of sentimental voice-over, kinetic camera, and doo-wop grandiosity by using the aesthetic to pan through a retirement home instead of the Copacabana.

The rest of the movie remains in this key: It’s an elegiac, wistful look at the wickedness of the 20th century, with all of its brash men left to die brutally, alone, and for nothing. Beautiful and wrenching, The Irishman shows Hoffa losing himself in the gray area that the Mafia created between itself and the Teamsters, and his death at the hands of Sheeran aptly represents the century’s tragic loss of working-class solidarity. (It would not be much of a stretch to say that the erosion of labor union membership, and the resulting cynicism, produced the conditions wolves like Belfort needed to truly thrive.) Perhaps the biggest gut punch of all is that Sheeran loved Hoffa and was but a loyal foot soldier in killing him, devoted to a cause that he never understood beyond its vague patriarchy, communal inclusion, and, of course, financial benefits. By the end of the movie—an intentionally long and painstaking 209 minutes—Sheeran is drawing a blank on his deathbed, surrounded only by a disinterested nurse and a priest. In a likely nod to one of Scorsese’s greatest influences, The Searchers, our last sight of him is through the frame of a barely open doorway. He is on the other side of history. Toughened by his experience in World War II, Sheeran never knew a version of American success or brotherhood that wasn’t entangled with the professionalized annihilation of life. His body count is entirely too high for Sheeran to be a sympathetic figure, but the sin he’s caught up in is most assuredly above his pay grade and predates his entrance into the profession of “painting houses.”

It’s that preceding, foundational American evil that Scorsese is after in 2023’s Killers of the Flower Moon: the theft of land, life, and dignity from Native Americans, perpetrated by men with eyes widened by the myth of Manifest Destiny. In a recent interview about the movie, Scorsese said that it—and the nonfiction book of the same title it’s based on, by David Grann—“reflects who we are as a Western culture. … What are the values that we brought to this new land?”

Scorsese’s perspective on the story is markedly different from the book’s, locating the deeply set seed of American wantonness in a marriage between a white man with dubious intentions (DiCaprio) and his Native American wife (Lily Gladstone). The thing that comes between the Osage Nation of Oklahoma and the rest of the country—referred to, not so coincidentally, as “wolves” in the movie’s first trailer—is the great wealth they discover when it turns out that their land is rich with oil. The forthcoming movie is one of Scorsese’s largest statements ever, extending his dissertation about authentic 20th-century menace into its most integral chapter yet about the character of America. For all the decades Scorsese has portrayed it, the United States has been a country built on the flawed yet irresistible premise that power can always grow without consequence or atonement. The resulting, feverish tragedy-cum-romance, gorgeous and horrible, is the collective dream and reality he was born to put to film.

John Wilmes is a writer and professor in Chicago. Follow him on Twitter at @johnwilmeswords.