Martin Scorsese’s 81 Greatest Movie Characters, Ranked

In celebration of the upcoming release of ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ (and his 81st birthday next month!), we’re counting down the greatest figures of the legendary director’s careerFor roughly 50 years now, since the release of Mean Streets in 1973, really, Martin Scorsese has captivated moviegoers with his stylish, nostalgia-tinged depictions of (mostly) 20th-century America. It’s hard to say if Scorsese has dedicated himself to any particular genre or visual signature, but one thing most Scorsese films have in common is a wealth of great characters. Sure, Scorsese has his favorites—the gangsters, the religious figures, the corrupt politicians—but much like the settings and tones of his filmography, the roles range across a breadth of personalities.

From the most intimate of character studies to films anchored by large ensemble casts, Scorsese has crafted figures behind some of the most indelible lines, scenes, and movies in American cinema. In honor of his newest release, Killers of the Flower Moon, we decided to revisit those characters and determine the best of them all within the Scorsese canon. The only rule we established for this ranking was to focus exclusively on characters who have appeared in his 27 (as of now) feature films. And since Scorsese will turn 81 on November 17, we figured we’d cap the list at that number, in celebration.

So, with all of that said, happy birthday, Marty, and let’s get into the ranking.

81. Captain Queenan (Martin Sheen), The Departed

Upon my umpteenth viewing of The Departed, I noticed something new: Captain Queenan is the only major character in the film who never swears (unless you count the absolutely filthy way he keeps saying “cawp”). Martin Sheen brings his patented West Wing gravitas to the role, and he’s the calming father figure in the room amid everyone else just playing their little games. Queenan is too paternal for the game—he’d rather feed his undercover agent a late supper than call him a cunt—and he consequently suffers the film’s most brutal and tragic death. You could even argue it’s the least-deserved violent death in the entire Scorsese oeuvre (and we’re talking about an oeuvre with a not-insignificant amount of violent death). Scorsese has always gotten a lot of mileage out of the inevitability of tragic violence in his films, but the real tragedy of Captain Queenan is that his fate never felt inevitable. —Daniel Joyaux

80. Mary Magdalene (Barbara Hershey), The Last Temptation of Christ

We’re introduced to Barbara Hershey’s Mary Magdalene as she has sex with one in a long line of men who wait to pay for her services and half watch those ahead of them. Jesus (Willem Dafoe) lingers until nightfall, when everyone else has left—when Mary assumes she’s alone and is trying to sleep. Morose and self-pitying, he tells her that he’s going to the desert and that he’s seeking her forgiveness. Mary will have none of it. Hershey’s delivery of four consecutive lines—“You’re pitiful. I hate you. Here’s my body. Save it.”—in a clipped whisper will hang over the rest of The Last Temptation of Christ as both an indictment and a challenge to Jesus. Mary lives as her own character, too: The scene in which Jesus saves her from being stoned is a vehicle for his political transformation, sure, but an entire gospel could be written about Mary’s face and posture as she’s dragged across the desert ground by bored and brutal men. —Paul Thompson

79. Leigh Bowden (Jessica Lange), Cape Fear

Although Cape Fear was a commercial project and not as close to Scorsese’s heart as some of his other films, it does showcase his usual interest in the tribulations of relationships between men and women. Faced with her husband’s denial of and overly confident response to the threat of Max Cady, Leigh Bowden sees the foundations of her typically heteronormative coupling crumble under her and her family. Lange brings her fearlessness as a performer to Leigh, a woman who reveals her strength and courage as Cady’s terrorizing grows more violent and gets ever closer to their home. More than simply a self-sacrificing mother and wife, Leigh is smart and understands Cady better than anyone, which allows her to save her family after bargaining with the criminal in a terrifying and heartbreaking monologue that lets Lange’s raw sensibility and star power shine. —Manuela Lazic

78. Walter “Monk” McGinn (Brendan Gleeson), Gangs of New York

For a while, he’s the only hope the Irish have. A man with 44 notches in his shillelagh (undeniably badass), he brings Amsterdam Vallon back to the right side of the war in New York City and reminds him of where and who he came from. Together they begin to create a new future, one of equity and safety, where the men who dare call themselves “native” Americans won’t be able to squash the life out of those whom they deem foreign. A violent enforcer as a young man, he grows up to be the sheriff of New York, a champion of the “democratic way.” And in the end it doesn’t matter at all: Bill Cutting still drives a cleaver into his back and finishes him off with his own club—the 45th notch. Walter McGinn wanted to make a new world. The only problem was he forgot he was still living in the old one. —Andrew Gruttadaro

77. Kiki Bridges (Linda Fiorentino), After Hours

After the cab ride from hell acts as Paul Hackett’s portal into another world (actually 1985 Soho, but same difference), Kiki Bridges quickly acclimates him to the surrealism of his new environment. Paul encounters Kiki when she’s wearing only a miniskirt and black lace bra, slathering papier-mâché onto a life-size sculpture of a person in distress, and she convinces Paul to take part and remove his shirt. But the night is young, and that bra is not long for this world. Soon there are massages and handcuffs and attempted mohawk assaults at Club Berlin (where it’s Mohawk Night, obviously), all of which Kiki reacts to with the same look of sultry bemusement—like the sexiest version of “whatever” that you’ve ever seen. If Rosanna Arquette’s Marcy is Paul’s gateway drug into the wild world of After Hours, Linda Fiorentino’s Kiki is his crystal meth. —Joyaux

76. Tony “Pro” Provenzano (Stephen Graham), The Irishman

There are so many heavy hitters who also happen to be regular Scorsese collaborators in The Irishman that it’s hard to stand out from the pack, but Stephen Graham did so with aplomb. As the mobster Tony Provenzano, Graham has an antagonistic relationship with Al Pacino’s Jimmy Hoffa, which leads to my favorite scene in the film: the two characters bickering over Tony’s late arrival to a meeting in Florida. There are few actors who can chew through scenery as well as Pacino, but Graham is cooking with gas here. No wonder Graham called The Irishman his version of being in a Champions League final—give him the man of the match. —Miles Surrey

75. Julie (Teri Garr), After Hours

There are a number of scene-stealers in Scorsese’s nightmare-fuel screwball comedy After Hours, but Teri Garr’s Julie might be responsible for the film’s single funniest joke. Julie initially presents herself as the warm presence Paul desperately needs in his unrelenting quest to get home, only to quickly reveal herself to be another bizarre obstacle in his hellish night. One minute he’s on her couch, near tears, venting about his past few hours; the next, she’s asking him to fondle her beehive. Paul, trying to get the flirtatious and obsessive Julie off his back once and for all, asks to exchange phone numbers so that he can be on his way. It might just be the complete seriousness with which she replies, “My number is 544-33, very easy to remember,” that earns Julie her spot on this list, not to mention her indignation at Paul’s slightest mention that that might not be enough numbers. Needless to say, Garr makes the most of her limited screen time. —Julianna Ress

74. Cristóvão Ferreira (Liam Neeson), Silence

For all the bloody mob killings—the bodies hanging in meat lockers and ground up in trash compactors, stuffed in trunks and rotting in marshes—the acts of violence in Scorsese’s filmography that are most difficult to watch might be the torture scenes that take place in Silence, in large part because they beg the question “For what?” The overlooked, poorly marketed passion project sees the intractable clashing of different faiths and cultures and raises it the anguish and uncertainty that live inside individuals. Silence follows two Portuguese priests as they venture to Japan to search for an older priest who is rumored to have renounced his faith. In the opening hour of the film, that one-time mentor, Cristóvão Ferreira (Liam Neeson), looms as a Colonel Kurtz figure. But Ferreira has not cracked up or amassed a cult or retreated to the shadows; he seems to believe, quite rationally, that the missionary project is ill conceived. And yet when Andrew Garfield’s Sebastiao Rodrigues is confronted with the choice to apostatize or allow other Christians to suffer in perpetuity, Ferreira’s pivot is given new weight and new ambiguity—and Neeson has already imbued him with more than enough depth to support it. —Thompson

73. Warden (Ted Levine), Shutter Island

“If I was to sink my teeth into your eye right now, would you be able to stop me before I blinded you?” It’s a good question, and one that Leonardo DiCaprio’s FBI man Teddy Daniels is ill equipped to answer—not least of all because the guy asking it is ostensibly on hand to keep the peace. Of course, you don’t cast the man who famously played Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs as a good cop, and Ted Levine’s extended cameo in Shutter Island as Ashecliffe’s warden marks a small, triumphant victory lap for one of our most menacing character actors. In less than two minutes of screen time, Levine etches a memorable—and hilarious—portrait of authoritarian bloodthirst while also ramming home the script’s thematic payload about violence and retribution. —Adam Nayman

72. Mary Burke (Patricia Arquette), Bringing Out the Dead

As is typical for a film penned by Paul Schrader, Bringing Out the Dead features a vulnerable woman in need of rescue—yet Mary Burke is somehow even more angelic than other Schrader women, thanks in large part to Patricia Arquette’s delicate performance and Scorsese’s tender view of her. As she opens up to Nicolas Cage’s Frank, Mary reveals a complex mind uninterested in sentimentalism but in touch with the tumultuous feelings that her father’s coma brings up. Arquette’s chemistry with Cage also brings out the best in the actor, who may be better known for his expressionist turns, but here he demonstrates his great ability to simply listen. In turn, he makes us pay equally close attention to Arquette’s childlike voice and her calming aura in this otherwise nerve-racking film full of despair, regret, and suffering. —Lazic

71. Inquisitor Inoue Masashige (Issey Ogata), Silence

In a 2017 interview with Vox, Japanese actor Issey Ogata explained that he didn’t see his character in Silence, the inquisitor Inoue, as a villain, but rather as a man doing a job. His vocation is the breaking of wills, a mandate that manifests in the torture of any and all practicing Christians until they either recant by trampling on an image of Christ or die trying to maintain their defiance. It’s a tricky role juxtaposing relaxed wisdom and meticulous cruelty, and Ogata—who was brilliant as Emperor Hirohito in Aleksandr Sokurov’s 2006 biopic, The Sun—pulls it off with nimble, seriocomic finesse. —Nayman

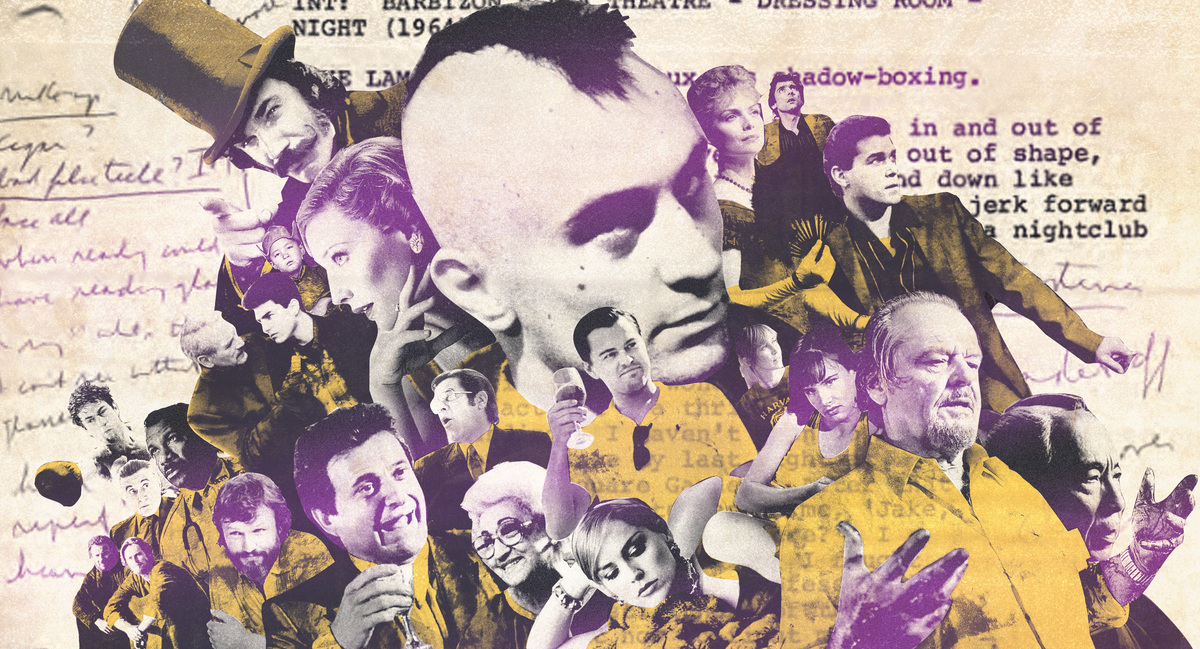

70. Marcus (Ving Rhames), Bringing Out the Dead

In the most memorable scene of Bringing Out the Dead, Ving Rhames’s devout paramedic, Marcus, performs an improvised resurrection ritual on an OD’ing rocker at a goth-y nightclub—a means of distraction allowing his colleague Nicolas Cage to do his job. Throughout his career, Scorsese has specialized in mixing the sacred and the profane, and here, the confluence proves stirring and hilarious: What starts as sarcastic subterfuge mutates into something genuinely suspenseful and stirring, with Rhames—at his charismatic peak—going into full-on medicine-show mode by the end. “Rise up, I.B. Bangin,” Marcus exhorts, and for a moment, it’s as if the whole movie had gotten a shot of adrenaline—straight to the heart and into the canon of Scorsese’s most exhilarating sequences. —Nayman

69. Claude Kersek (Joe Don Baker), Cape Fear

Long before Ethan Hawke mixed booze with Pepto-Bismol in First Reformed, Claude Kersek was on the case in Cape Fear. Played by the legendarily leathery Joe Don Baker—an axiomatic presence in ’90s studio thrillers, usually as some kind of mercenary sleazeball—Kersek bills himself as a security guru and professional intimidator, but he can’t scare Robert De Niro’s Max Cady off from his former lawyer Sam Bowden (Nick Nolte); the scene in which he first tries is a master class in how quickly puffed-up posturing deflates in the presence of true malevolence. Finally, Kersek’s tough-guy act is just that—an act—and he gets his comeuppance in what might be the purest jump-scare moment of Scorsese’s entire career. —Nayman

68. René Tabard (Michael Stuhlbarg), Hugo

If Georges Méliès in Hugo is a stand-in for Scorsese himself, then René Tabard is all of us. He’s a scholar and expert on Méliès, but also completely taken by him, like a gushing fan (and this was 1931, long before “gushing fan” was an obvious pejorative). When Tabard talks about having met Méliès once as a boy and watching him make films in the early years of the 20th century, it’s perhaps the purest moment of wide-eyed wonder Scorsese has ever allowed himself to capture. And that’s saying a lot for a man who’s made three entire films about the quest to understand God. In that moment, we are all René Tabard, regaling the youth about the moment that cinema changed our life. And Michael Stuhlbarg, six years before he gave his achingly measured speech at the end of Call Me by Your Name, finds the perfect tenor and cadence for the personal gravity of his story. —Joyaux

67. Flo Castleberry (Diane Ladd), Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore

Flo’s tough. She’s smart. She swears like a sailor, if the sailor were also Foghorn Leghorn. “You can kiss me where the sun don’t shine,” she says to her boss, Mel. She’s got a beehive hairdo that looks like it was inspired by the Leaning Tower of Pisa. She’s a waitress in a shitty Arizona diner in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, where her survival strategy is to be even more vulgar than the truckers who constantly harass her. “I heard the only way you can get it up is to slam it in a door.” (She also says that last line to her boss.) Diane Ladd finds a deep well of humanity in what could have been a caricatured role. She made Flo so real, in fact, that the character kept going, played by Polly Holliday in the sitcom Alice, which was inspired by the film. Eventually, she even got a short-lived spinoff sitcom of her own, simply called Flo. —Brian Phillips

66. Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), Taxi Driver

In some basic ways, Betsy is just a boilerplate stand-in for every beautiful woman that troubled young men feel mortally destined to be rejected by, and it’s no accident that Taxi Driver never even gives her so much as a last name. But Cybill Shepherd infuses Betsy with such a graceful gentleness and curiosity that Travis Bickle’s eventual failure with her feels like the self-inflicted wound that it clearly is, rather than the tragic inevitability of her beauty that the film seems to be initially setting up. And Betsy’s unforgettable journey of cringey expressions when Travis takes her on a date to a porno theater is pop culture’s original “Why are men?” moment. —Joyaux

65. Tom Schorr (John Heard), After Hours

In real life (or at least in pop culture), bartenders are the ultimate sages of sound life advice, society’s duly licensed therapists before licensed therapists existed outside Hollywood and the Upper East Side. And at first, John Heard seems to bring that exact kind of calming wisdom to Tom the Bartender (as he’s named in the After Hours credits). But within a few minutes of offering Paul Hackett a lifeline in the form of subway fare, Tom is suddenly kicking the shit out of his own cash register. As with every other man punching the clock in After Hours—cabbie, bouncer, subway booth attendant—Tom is comically unhelpful. But with Tom, this unhelpfulness isn’t merely played for laughs; because of his station, or perhaps because of what Heard brings to the role, Tom’s unhelpfulness feels like a betrayal. And it’s so effective that even when he finds out his girlfriend has just OD’ed, our first thought is to be annoyed that he’s let Paul down yet again. —Joyaux

64. Priest Vallon (Liam Neeson), Gangs of New York

Liam Neeson’s face is the first one the viewer sees in Gangs of New York, Scorsese’s 2002 Manhattan-core valentine to mid-19th-century risk and revenge, and Neeson’s close shave is the first thing the viewer hears. Life is grim here, and Dead Rabbits leader “Priest” Vallon is with us for less than the first 10th of the film’s running time. (The battle that kills him is as gutting as anything I ever saw on Game of Thrones.) Still, in this world, the blood stays on the blade, so the Priest’s legacy hangs over the entirety of the picture, dripping down onto the minds of narrator and villain alike. —Katie Baker

63. Masha (Sandra Bernhard), The King of Comedy

Although called a flop by Entertainment Tonight on New Year’s Eve 1983-84, The King of Comedy has a lot going for itself, including Sandra Bernhard’s heralding of the dawn of the modern fangirl, one who is wild not about a singer or an actor, but about a comedian and TV personality who comes into people’s living rooms every night, giving them the impression that they know him personally. Much like De Niro’s aspiring stand-up comedian, Rupert Pupkin, Masha at first seems to be a one-dimensional character: She’s just defined by her alarming obsession. But Bernhard knows that people with frenzied fantasies don’t know they’re deluded and manages to make each of Masha’s absurd and antisocial reflections about what she needs and deserves from her idol, Jerry Langford, look sincere and almost logical. Masha takes a pragmatic, if unhinged, approach to try to get Jerry all for herself, which belies her buried despair and loneliness and irrational belief that having him will solve all her problems. At once terrifying, funny, heartbreaking, and stylish, Masha is an unforgettable, iconic presence in a film that only gets more unnerving with each passing year. —Lazic

62. Spider (Michael Imperioli), Goodfellas

You know you’re a fucking mumbling, stuttering little fuck, you know that? Michael Imperioli plays poor Spider as bumbling, doe-eyed, and nervous—probably about the way you or I might have behaved were we asked to bartend a poker game for hotheaded and heavily armed members of the Lucchese crime family. It’s not Spider’s fault that he runs afoul of Joe Pesci’s Tommy, the hotheadedest of them all, and he really takes it pretty well when Tommy decides to take revenge for a missed drink order by shooting him in the foot. You’re almost proud of the poor little mafioso dweeb when he works up the nerve to tell Tommy to go fuck himself at the next poker game. Tommy, on the other hand? Adios, Spider. —Claire McNear

61. Francine Evans (Liza Minnelli), New York, New York

The critical reclamation of Scorsese’s work from the 1980s has come in waves; you’ll find people today who stump for movies like 1999’s Bringing Out the Dead, which was dead on arrival at the box office and with critics, or Shutter Island, which became a megahit despite its suboptimal February 2010 release date and is now a serious cult object. But with the possible exception of Kundun, there is no movie in his filmography that is as universally disliked as 1977’s New York, New York. “Disliked” might even be too strong—today, the Scorsese–De Niro collaboration that slots directly between Taxi Driver and Raging Bull hardly seems to exist. But for all its dull stretches and the odd stiffness from its supporting cast (and for all the overwrought moments in which De Niro is capital-A Acting), the one undeniable element is Liza Minnelli’s Francine, an ex-USO entertainer turned passenger who’s in a fraught relationship with De Niro’s volatile saxophonist. Minnelli is one of the only performers on earth who could maintain the same electricity as she moves in and out of musical numbers, who could seem at once too theatrical for everyday life and too natural for show business. —Thompson

60. Amos (Forest Whitaker), The Color of Money

The idea was that The Color of Money would be Tom Cruise’s coming-out party as a serious actor—a showcase for the erstwhile Maverick to hold his own against Paul Newman. Cruise is good in the film, but the real find was Forest Whitaker, who shows up out of nowhere as a talkative, self-deprecating hustler who casually mops the floor with Newman’s aged pool shark, “Fast” Eddie Felson. “I don’t want no bad feelings,” Amos tells Eddie after their game, and the wonder of Whitaker’s performance is that he seems to mean it—he’s a nice enough guy. But he’s also a killer, and the look in Newman’s eyes of disgust, fear, and respect speaks volumes. —Nayman

59. Gail (Catherine O’Hara), After Hours

Male anxiety is the satirical subject of After Hours, which just keeps conjuring up eccentric, exotic women for Griffin Dunne’s existentially emasculated protagonist, Paul, to run and cower from. With respect to the murderers’ row of comic actresses in the supporting cast, the film’s ace in the hole is Catherine O’Hara, fresh off SCTV and piloting an ice cream truck as the seemingly helpful—but quickly bloodthirsty—Gail. Beginning with the sly signage of her vehicle (“Mister Softee” being a dig at Paul’s lack of machismo) and extending through her brief, brilliantly malleable performance, Gail is a singularly funny creation; O’Hara would go on to cult stardom in the comedies of Christopher Guest and scoop up awards for Schitt’s Creek, but After Hours captures her in her outlandish, blue-eyed prime. —Nayman

58. Georges Méliès (Ben Kingsley), Hugo

Scorsese once said that the job of a filmmaker is to get an audience to care about your obsessions. If that’s true—and who am I to argue with Martin Scorsese—then Ben Kingsley’s performance as Georges Méliès in Hugo is the simplest distillation of Marty doing that job. We tend to think of Scorsese’s filmography as being about cycles of temptation, sin, and regret, but Marty has always been one of cinema’s greatest historians and preservationists, and Hugo is his only narrative feature that’s overtly about that particular obsession.

Hugo is Scorsese’s most magical work, and Méliès (who literally began his career as a magician) is his purest on-screen analogue. The character represents all of the pain, joy, fear, and magic of not just creating cinema, but also of having created it, in the past tense. How do we remember the past of this medium that we so love? How do we preserve it and keep it alive? What does it mean for the past to keep breathing? Hugo is Martin Scorsese’s attempt to address some of the thorniest and most important questions of his life, and Méliès is the beautiful, transcendently creative vessel he steps inside to do so. —Joyaux

57. J.R. (Harvey Keitel), Who’s That Knocking at My Door

You can’t help but think that the protagonist of Scorsese’s very first feature film has a lot in common with the director himself. J.R. is pulled by three different identities: one as the member of a callous neighborhood gang, one as a hopeless-romantic-slash-movie-buff, and another as a dedicated Catholic. His struggle to navigate all three makes him both endearing and despicable all at once—and foreshadows Scorsese’s career. —Alyssa Bereznak

56. Amsterdam Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio), Gangs of New York

If we’re being honest, Daniel Day-Lewis’s magnetic, frightening portrayal of Bill the Butcher in Gangs of New York easily overshadows Leonardo DiCaprio’s work as Amsterdam Vallon. (While Day-Lewis has three Oscars to his name, one could argue he deserved a fourth after losing out to Adrien Brody’s performance in The Pianist.) But in looking to avenge his father’s death by joining Bill’s gang and getting closer to him, Amsterdam allows DiCaprio to inhabit a person willing to lose a part of himself for the closure he seeks. It’s the type of all-consuming role that would earn DiCaprio more acclaim in movies like The Departed, but even if it’s not a top-tier Scorsese-DiCaprio collaboration, Gangs of New York remains a worthy entry in the actor’s impressive CV. —Surrey

55. Billy Batts (Frank Vincent), Goodfellas

RIP to a real one. Billy Batts was essentially a mustachioed Icarus who, for a bit more than a few laughs, fucked around and found out. Fresh out of the can, he thought he’d spotted a punching bag. Luckily for us, dude picked the wrong one. As Outkast rapped on “ATLiens,” “Get your fucking shine box and your sack of nickels.” Men like Billy walked so ones like Big Boi could run. —Lex Pryor

54. Captain Ellerby (Alec Baldwin), The Departed

In a movie full of high-efficiency performances, Baldwin’s Ellerby outdoes them all. He has only a handful of lines, and even fewer scenes, but every single one of them is crackling with humor, as the New York–born Baldwin nails the vibe of a Boston cop who drinks too much coffee and smokes too many cigarettes. This line—“I’m gonna go have a smoke right now. You want a smoke? You don’t smoke, do ya, right? What are ya, one of those fitness freaks, huh? Go fuck yourself.”—is 30 words, but Baldwin makes it feel like five. His thoughts on marriage are unparalleled (“People see the ring, they think, At least somebody can stand the son of a bitch; ladies see the ring, they know immediately you must have some cash or your cock must work”), and he gets to deliver one of the most pointed lines in the movie—even if you might not immediately notice its importance because of who’s delivering it. Patriot Act! Patriot Act! I love it, I love it, I love it. —Gruttadaro

53. Lester Diamond (James Woods), Casino

Maybe you think the nightmare scenario is that your partner has an ex who’s better-looking than you. Maybe you’re worried they’re richer, smarter, or further ahead in their career. You’d be wrong. The nightmare scenario is that you’ve been sent from Chicago to Las Vegas to run the mob’s operation in the city, made yourself into not only a model crook but also an exacting hotel proprietor, seduced the Strip’s beloved-but-volatile it girl, and married her, only to find out she’s hung up on motherfucking Lester. James Woods in this movie looks like a gecko with liver disease, sweating through his fake Gucci coats and snorting up what one would have to assume are the alimony payments from a half dozen women he’s—how do we put this?—charmed. “Be a man,” De Niro’s Ace Rothstein implores him across a Formica table minutes after he’s discovered Lester’s plot to steal his wife’s savings. “Don’t be a fucking pimp.” But this is Lester, baby: Pimping is all he knows. —Thompson

52. Danielle Bowden (Juliette Lewis), Cape Fear

Cape Fear allowed Scorsese to prove that he could be as attuned to teenage girls coming of age as to teenage boys. Danielle is a normal 15-year-old, a little rebellious and stubborn, and slowly discovering her sexuality and the violence of the world. Her disillusionment toward her parents and their authority is heightened and her love for them tested by Max Cady bursting into their lives. Torn between resentment and affection, she is particularly vulnerable to Cady’s tactics of persuasion, and Juliette Lewis holds her own impressively in her dangerous seduction scene with De Niro, translating beautifully the curiosity and need for understanding that teenage girls typically experience. What also transpires in that scene and throughout, however, is her sharp intelligence (the character is much like her mother, Leigh, in that way), and Lewis’s performance is full of not only childish spontaneity and rage, but also wit. —Lazic

51. Joey LaMotta (Joe Pesci), Raging Bull

Tommy DeVito, the little ball of id Joe Pesci plays so perfectly in Goodfellas, is a role so iconic that it would color everything he did after 1990—and become a lens retroactively applied to the work he did before. And to be sure, there are moments in Raging Bull when Joey LaMotta does explode, trashing a nightclub or lashing out over a craggy payphone connection. But he does his most impressive work when the gravitational forces are reversed, when he’s poking and prodding his boxer brother to elicit the reactions (and career decisions, and weight fluctuations) he wants. Pesci is at his best when he gets to play Joey’s surprise (and later, sorrow) over the extent to which Jake (Robert De Niro) really can become the “animal” Joey so venomously taunts him for resembling. This is a master class in minute calibration, a never-ending cycle of reaction and manipulation, all in the name of fraternal love. —Thompson

50. Dr. Madolyn Madden (Vera Farmiga), The Departed

In the whirlwind of double crossing, “microprocessahs,” and cheese-eating fucking rats that is The Departed, there’s a good old-fashioned love triangle involving two cops and their unit’s psychiatrist. Vera Farmiga’s Dr. Madolyn Madden stands as a moral center for Billy Costigan, Colin Sullivan, and the audience, despite the infidelity and questionable prescription practice of placing two Valium pills in front of a begging patient. In addition to calling a croissant a French doughnut and offering bits of sage wisdom like “Death is hard. Life is much easier,” Madolyn provides some relief from the film’s tangled web of deceit. That makes her the perfect person to highlight when we’ve reached the tipping point and everything is beginning to unravel. When Madolyn shoots daggers of pure disgust at Matt Damon’s Colin after she discovers evidence of his role in the Irish mob, Colin’s fate is sealed without her even having to say anything. —Ress

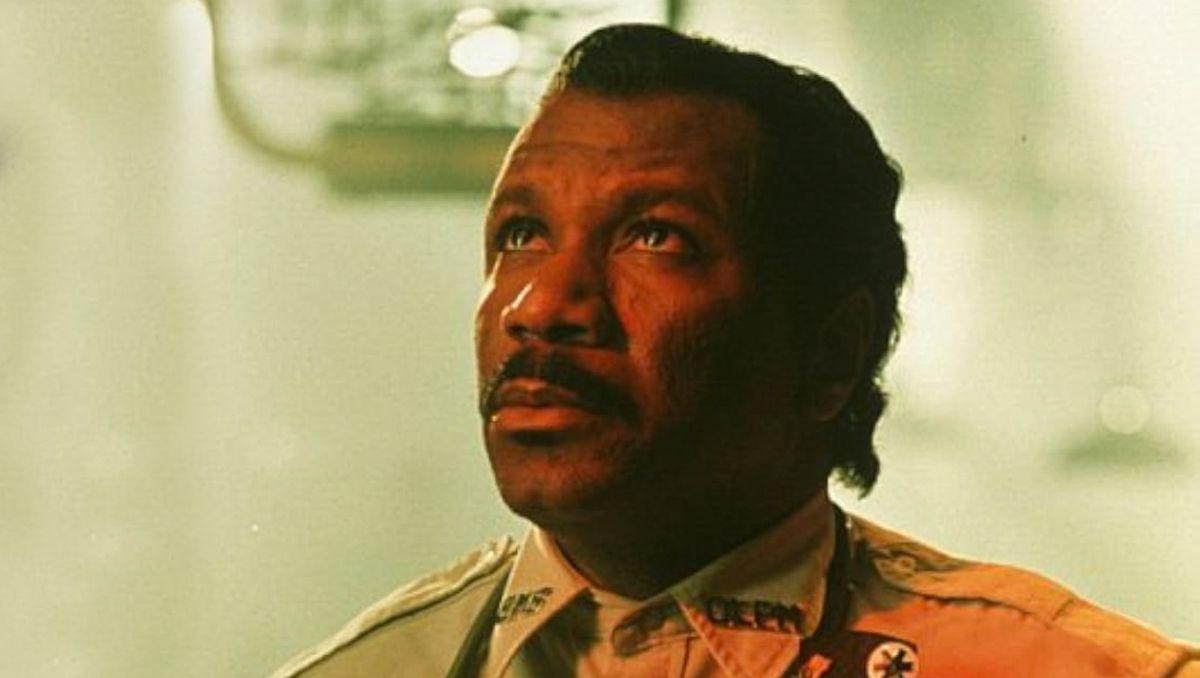

49. Jesus Christ (Willem Dafoe), The Last Temptation of Christ

Martin Scorsese has been reckoning with his Catholic faith throughout his filmography, so it’s only natural that he’d make a movie about Jesus Christ, though not without some controversy at the time of release. Anchored by a monumental performance from Willem Dafoe as the son of God, The Last Temptation of Christ is a fascinating project in that it allows the character to feel so human. This version of Jesus isn’t just trying to resist familiar temptations—fear, lust, doubt—but to make sense of the divine destiny presented to him. As an agnostic, I don’t have any skin in the game, but it’s easy to admire Scorsese’s underlying message: doubt is an essential part of any person’s faith, and recognizing that doesn’t make one weaker for it. —Surrey

48. The Dalai Lama (Multiple), Kundun

Come on, it’s His Holiness! Just because you’ve never seen Kundun doesn’t mean the 14th Dalai Lama—plucked from obscurity as a child and forced into the role of Tibet’s spiritual leader in a time of utter upheaval—isn’t a great Scorsese character. Christopher Moltisanti is somewhere nodding his head. —Gruttadaro

47. Judas Iscariot (Harvey Keitel), The Last Temptation of Christ

The Last Temptation of Christ is like a tonal house of cards: At any point, the introduction of a new character from scripture or a new crucible for Jesus to navigate could render the whole thing ridiculous, like self-published historical fiction or badly cast dinner theater. But rather than stick doggedly to a single note, Scorsese lets his cast read their characters in wildly different ways, to render them as if they’re in totally different movies. And so we get Harvey Keitel’s take on Judas, who is there not to deceive or betray but to hector: When he abandons his orders to kill Jesus, suspecting his friend could be the Messiah, he essentially warns him, “I swear to God, if you fuck up …” Last Temptation was wildly controversial before it was even released, the subject of endless, shrill protesting from people uninterested in what the text might have to say. But its most provocative tensions are all embodied in Judas, who is disgusted by Jesus’s collaboration with the Romans and later convinces him to follow through on sacrificing his life. That Keitel plays all of this like an irritated outer-borough cabdriver makes it all the more compelling. —Thompson

46. Paul Cicero (Paul Sorvino), Goodfellas

If the aim of Goodfellas is to probe the appeal, setup, and limitations of organized crime as a stand-in for family units, Paul Cicero is no mere Don—the man’s a fully-fledged patriarch. As a leader and father figure, Paulie’s commanding and also, kind of, full of shit. Paul Sorvino imbues the character with a palatable flawed stoicism. The man who plucks capos out of working-class obscurity is the same one who coughs up a paltry “3,200 bucks for a lifetime” before disowning them. Truth is, there’s honor and dishonor among thieves, and also the same among dads. —Pryor

45. Morris Kessler (Chuck Low), Goodfellas

Chuck Low’s performance turns Morrie, the wig shop owner who pisses off the wrong mob guy, into one of the most lovably annoying characters in movie history. The way he relentlessly needles Jimmy Conway after the Lufthansa heist will always be stuck in my brain.

“Jimmy, I need the money.”

“... I need the money.”

“I did what I had to do, I need the money.”

Poor Morrie. He loves his wife. He’s not a violent psychopath like his connected friends. But he won’t shut up. And so Jimmy has Tommy DeVito jam an ice pick into the back of his head. Even in death, Morrie stays true to his promise: his wig doesn’t come off. –Alan Siegel

44. Teddy Daniels (Leonardo DiCaprio), Shutter Island

Entering the 2010s, Scorsese could do whatever he wanted, and that meant crafting Shutter Island, a simple film about the complex inner workings of the mind of U.S. Marshal Teddy Daniels. Teddy was sent to Shutter Island to investigate Ashecliffe Hospital, a facility for the criminally insane. As Teddy’s day exploring Shutter Island unfolds, he battles migraines, delusions, and his sanity, slowly realizing the horrific reason he’s really on Shutter Island: to find himself. Essentially, Scorsese put viewers inside Teddy Daniels’s mind. But the alter ego Teddy was only a creation of Andrew Laeddis, who had murdered his wife after she drowned their children. Racked by guilt, Laeddis had constructed a personality whose sole purpose was to get to the bottom of the facility he was housed in. —khal

43. Vikki LaMotta (Cathy Moriarty), Raging Bull

Pass the Bechdel test, Raging Bull does not. In fact, Vikki LaMotta is a metaphorical and literal punching bag that her middleweight champ husband, Jake, returns to when he feels inklings of self-hatred and doubt. She’s nevertheless incredibly calm and collected, down to her blond Coke bottle curls and unwavering gaze. And ultimately her determination to live her life, stare down her husband, and call him on his bullshit makes her the most worthy opponent in his entire career. —Bereznak

42. Peggy Sheeran (Anna Paquin), The Irishman

Maybe the only genuinely heartwarming moment in Scorsese’s tragic masterpiece The Irishman is the montage of a young Peggy Sheeran (Lucy Gallina) playing mini golf and eating sundaes with Al Pacino’s Jimmy Hoffa. Of course, there’s still a twinge of sadness under it all, watching a child befriend her Mafioso father’s associate and knowing it just can’t end well. That doesn’t make it hit any less hard when an adult Peggy (Anna Paquin) watches Hoffa’s disappearance unfold on TV. When Robert De Niro’s Frank mentions he has yet to speak to the newly widowed Jo Hoffa, Peggy understands exactly what has happened. Still, she asks, “Why haven’t you called Jo?” with heartbreak and rage plastered across her face. It’s so little, and still more than she really needed to say to confirm what she already knew.

Frank notes that this is the last time Peggy ever spoke to him, but he sees her one more time years later, showing up at her job only to be met with the same expression she had on that day in 1975. We see Peggy in brief flashes throughout The Irishman, because that’s how Frank saw her: She existed in his periphery as a whole life unfolded that he completely missed out on. Her eyes tell the story of a daughter hurt by her father in ways he never even noticed. —Ress

41. Wizard (Peter Boyle), Taxi Driver

In Taxi Driver, Travis Bickle calls himself “God’s Lonely Man,” but it’s not like he doesn’t have friends. Take Wizard (Peter Boyle), an older cabbie who represents the protagonist’s potential future as an embittered crank—spewing racist, sexist, homophobic bile as if it were the wisdom of the ages. “I envy you your youth,” Wizard tells his younger colleague, and Boyle—who was coming off his own angry-man triumph in the vigilante drama Joe—imbues the sentiment with exactly the right blend of pathos and contempt. One of the subtler themes of Scorsese’s masterpiece is the longing for transcendence—embodied in Jodie Foster’s naive prostitute, Iris—and Wizard embodies the idea from the other end: he’s a spent force, with no illusions about purity or innocence or a better world. (“We’re all fucked.”) However he got his handle, Wizard’s got no magic left. —Nayman

40. David (Kris Kristofferson), Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore

Ellen Burstyn rightly won an Oscar for her emotional tour de force as the eponymous heroine of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore; playing a widowed mother forced at regular intervals to defer—or forget—her dreams, she cuts a tough, empathetic figure. It seems like Alice has a man worthy of her in David (Kris Kristofferson), the laconic, kindly rancher who becomes her lover—and surrogate father to her son—in the film’s second half. But as with most of Alice’s partners, disappointment looms, and Kristofferson—at that time an up-and-coming music star—gives David exactly the right shadings to suggest what he’s capable of—and then even more depth in the aftermath of his transgressions, which leads to one of Scorsese’s tenderest endings. —Nayman

39. Mrs. Manson Mingott (Miriam Margolyes), The Age of Innocence

She’s only onscreen for about four minutes, but every line this recumbent Gilded Age grande dame speaks is a 110 mph fastball down the middle of the plate. “Your name was Beaufort when he covered you with jewels, and it’s got to stay Beaufort now that he’s covered you with shame.” Do not fuck with Edith Wharton. Do not fuck with Miriam Margolyes. “It’s these modern sports that spread the joints.” Our frilly daybed queen is here to kick ass and have multiple Pomeranians on her lap at all times. She’ll never run out of Pomeranians, but she’ll kick your ass anyway. Then she’ll give you tea. —Phillips

38. Carmen (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio), The Color of Money

Richard Price’s script for The Color of Money is masterful for the way “Fast” Eddie Felson (Paul Newman) and Vincent (Tom Cruise) force each other to recognize ugly things about themselves yet arrive in a place of optimism, though they may have to become blinkered to get there. Vince’s girlfriend and handler, Carmen, complicates this trajectory for both of them. A small-time thief who met Vincent after serving as a getaway driver in the burglary of his parents’ home, Carmen is at times wide-eyed and emotionally available; at others, that availability is wielded like a scalpel to trace fault lines in the confidence of the men around her. “You don’t know what you’re doing, do you?” Eddie asks Carmen when they meet in one of a thousand interchangeable pool halls. Scorsese and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio resolutely refuse to answer. —Thompson

37. Tommy’s Mother (Catherine Scorsese), Goodfellas

One of Catherine Scorsese’s most beloved cameos arrives when Robert De Niro’s James Conway and Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill swing by Tommy DeVito’s (Joe Pesci) mom’s house to pick up a shovel to bury the guy they’ve just whacked. (Technically, semi-whacked.) But their plan to sneak in and out is no match for Catherine, who dials up the Italian mother to 11: She hasn’t seen her son in ages, won’t he stay? His friends, they must be hungry! So there they sit, a trio of bloodstained criminals gathered around the dining room table of a kindly old lady who just wants to show off her dog paintings and convince her boy—her monstrous, murderous boy, who sweetly asks whether he can borrow his poor old ma’s knife, which he shortly uses to finish said whacking—to settle down with a nice girl. Martin Scorsese has said that most of the scene was improvised. Is there a meta-text here about Catherine’s take on her son’s choice to devote his life to portraits of violent men? Who cares—pass the gravy. —McNear

36. Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis), The King of Comedy

It’s hard to separate the fictional talk-show host Jerry Langford from the late Jerry Lewis throughout The King of Comedy. Along with sharing the same first name, a bunch of New Yorkers cheerfully greeting Jerry as he walks down the street certainly seems like a hat tip to the generation-defining comedian portraying him. But those similarities work to the film’s advantage—the price of being a celebrity is embodied by Jerry being unable to go anywhere without getting recognized, while at the same time feeling safest in a crowd. In that sense, fame becomes a prison long before Robert De Niro’s wannabe comedian Rupert Pupkin decides to kidnap Jerry. Even though it bombed upon release, The King of Comedy’s influence is so enduring that an Oscar-winning comic book movie was made in its image. Considering De Niro urged Martin Scorsese to make The King of Comedy after winning an Oscar for Raging Bull at the height of his own fame, it’s only natural that the actor took on the Jerry role in Joker. —Surrey

35. Marcy Franklin (Rosanna Arquette), After Hours

Scorsese’s questionable approach to female characters is well documented at this point, but at least with Marcy Franklin, he didn’t devolve into stereotypes. The trope didn’t really exist yet, but After Hours sets Marcy up to be a classic Manic Pixie Dream Girl by having her do a café meet-cute with an uptight office drone and lure him with the irresistible promise of bagel sculpture paperweights. (How could any mortal man refuse?) But while the evening sure does get manic from there, it ain’t very dreamy. Rosanna Arquette’s Marcy is a tragic figure, but much of the tragedy lies in her mysterious dichotomies. She’s a seductress, but she doesn’t seem very good at seducing. She’s vaguely interested in breaking Paul out of his shell, but she seems far more interested in having Paul break her out of her own shell (a job he’s woefully unqualified for). Marcy may be the white rabbit of Martin Scorsese’s most surreal vision, but she doesn’t lead Paul toward any self-discovery, and she doesn’t live long enough to experience any of her own. —Joyaux

34. Vincent Lauria (Tom Cruise), The Color of Money

You could argue that Paul Newman’s performance in 1961’s The Hustler invented Tom Cruise. The cocksure, slightly fragile swagger. The air of an incandescent talent imperiled by an equally incandescent overconfidence. The nuclear-grade mischievous grin. So it made sense, when Scorsese decided to helm a Hustler sequel, to pair Original Tom and Actual Tom in an epic, multigenerational Tom-Off. As the video game–loving toy store clerk Vincent Lauria (who also happens to be a natural-born star at the pool table), Cruise gives one of his most underrated performances of the ’80s—all the electric smarm of Risky Business crossed with the dawning maturity of A Few Good Men. And the presence of Newman’s older, wiser “Fast” Eddie Felson—a sort of dirtbag Ghost of Christmas Future—makes Vincent one of the most incisive (and fun) interrogations of the character Cruise has been playing in one form or another for the past 40 years. —Phillips

33. Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis), The Age of Innocence

“You gave me my first glimpse of a real life,” says the young, ambitious Gilded Age society man Newland Archer, played by Daniel Day-Lewis in Martin Scorsese’s 1993 adaptation of the Edith Wharton novel The Age of Innocence. “Then you told me to carry on with the false one.” He is talking to the woman of his dreams, Countess Olenska, who is played by Michelle Pfeiffer and is unfortunately also his wife’s disgraced cousin.

It’s a little hard to feel too bad about Archer’s predicament, considering that “the false one” includes being married to the angelic May (Winona Ryder). Tough break! But Day-Lewis (who cosplayed in 19th-century garb for months to prepare for the role, obv) nevertheless sells the performance perfectly, all the way to the film’s unexpected ending.

His chemistry with Pfeiffer feels lived in and appropriately desperate. He swings from being politely fed up with his bride one moment to shamelessly simping for the forbidden countess the next. Relatable, honestly, because inside us all are two wolves: dismissive and cringe. Archer is both. —Baker

32. Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci), The Irishman

At this point in Scorsese’s career, it’s impossible for his movies not to be meta-textual. And that also goes for the actors who have worked with him the most. Through Joey La Motta, Tommy DeVito, and Nicky Santoro, Pesci built a reputation as an on-screen hothead (Home Alone 2 only furthered this). He was the consummate chaos machine, filled to the brim with a combustible combination of charm and id. But after the ’90s, Pesci mostly receded from acting: Between 1995, when Casino came out, and 2018, he starred in only five movies. Scorsese lured him back for The Irishman, but you can feel that passage of time in his performance as Russell Bufalino. He’s quieter, more measured, wiser seeming. He’s still to be feared—at any time he may decide that it’s what it is—but in his every move you can feel a man grasping as time washes over him. The power of The Irishman is most on display in the arc of Russell: On top of the world one day, eating the finest loaf of bread and drinking the best glass of Chianti in a corner booth—and before you know it, he’s digging through whatever scraps the prison has and sipping on grape juice, his hands shaking as he goes to dip. Che successe successe: What’ll happen will happen. —Gruttadaro

31. Katharine Hepburn (Cate Blanchett), The Aviator

No question that Katharine Hepburn is a charismatic national treasure. Through Scorsese’s lens, she’s especially adventurous—a pants-wearing “country mouse” WASP who can hold her own on a golf course, at a cocktail party, and in the cockpit. In her brief stint with Howard Hughes, she is also a sage soothsayer, warning him on the edge of superstardom that the two of them were “not like everyone else.” It’s no wonder she lived rent-free in his head (and the screen of his private movie theater) long after their relationship crumbled under the weight of his paranoia. —Bereznak

30. Ellen Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer), The Age of Innocence

As Ellen Olenska, the beguiling cousin who married a problematic European abroad in The Age of Innocence, Michelle Pfeiffer says things like, “So, how do you like this odd little house? To me it’s like heaven!” Ellen possesses the kind of conspiratorial grin and sparkling eyes that can leave a fella reeling—which is exactly how she leaves the suddenly awakened Newland Archer. Which is all to say: Manic Pixie Dream Countess, am I right?! But what’s most interesting about Countess Olenska is the depth of her restraint. She is always strategically out of town or sending her polite regrets. She may be considered by some to be a fallen woman, but she’s got a stronger moral center than just about anyone in the film. All she’s missing is a pair of headphones that are playing some waltzing equivalent of the Shins, though in the original Edith Wharton book, she can be found “dancing a Spanish shawl dance and singing Neapolitan love-songs to a guitar.” We should all be so lucky. —Baker

29. Charlie Cappa (Harvey Keitel), Mean Streets

Even before the opening credits, we know that Charlie is painfully conflicted about the life he’s chosen. He wakes up startled from a bad dream, looks at himself in the mirror, and then struggles to fall back to sleep. The deeply religious young man is torn apart by his duty to God, his duty to his mobbed-up uncle, and his duty to his erratic friend Johnny Boy. Keitel’s performance infuses the character with a hypnotic mix of guilt and combustibility. And from the beginning, we know that his pal might doom him. When Charlie spots Johnny Boy with two women early in the film, he seems to know what he’s in for. “OK, thanks a lot, Lord. Thanks a lot for opening my eyes,” Charlie says in a voice-over. “You talk about penance, and you send this through the door. Well, we play by your rules, don’t we?” —Siegel

28. Mark Hanna (Matthew McConaughey), The Wolf of Wall Street

Matthew McConaughey barely cracks 10 minutes of screen time in The Wolf of Wall Street. It’s just that those minutes happen to include one of cinema’s most mesmerizingly bizarre lunches, in which McConaughey’s Mark Hanna takes out Leonardo DiCaprio’s newbie trader Jordan Belfort, then a straight-as-an-arrow try hard who loves his wife and wouldn’t dare drink on the job. Hanna immediately goes to town on a vial of cocaine, hands down the least weird thing to happen during the meal, which largely consists of straight-faced advice issued at a recreational stimulant–assisted pace. “Cocaine and hookers, my friend,” Hanna advises, before demanding precise daily metrics for Belfort’s, ahem, self-pleasuring. “You gotta pump those numbers up,” he instructs. “You gotta feed the geese to keep the blood flowing.” By the end of lunch, Hanna’s got Belfort joining in on his resolutely unexplained personal hype routine, both men humming as they thump their own chests. What else could Belfort do but take the rest of Hanna’s wisdom as gospel? —McNear

27. Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro), The Irishman

In the twilight of his life, mob hit man Frank Sheeran had a story to tell, and the tale he described to Charles Brandt became the basis for Scorsese and De Niro’s ninth collaboration. Scorsese gets to tell not just another mob tale but the mob tale through Sheeran. It’s essentially the same old story—Sheeran, a man who’s apt to cut a few corners to get ahead in the world, falls into the path of northeast Pennsylvania crime boss Russell Bufalino, becoming a valued hit man. Through this relationship and Sheeran’s time with Jimmy Hoffa—the man Sheeran has confessed to murdering—we get to fully understand the why of life in the Mafia: from the lifetime of scorn some children have for their parents to the personal sacrifices men like Sheeran had to make as both a family man and a friend to people like Hoffa. Scorsese goes a step further, allowing us to see how the lives of men like Sheeran, the “lucky” ones who live long enough to tell their tale after all of their running buddies have passed on, are still cold and lonely. There are no family and friends to spend the holidays with, no one around that remembers your glory days; there’s nothing but bad decisions to ponder, and whether it’s worth confessing those decisions before time is up. —khal

26. Naomi Lapaglia (Margot Robbie), The Wolf of Wall Street

Much like her husband, Naomi “The Duchess of Bay Ridge” Lapaglia is the extreme by-product of an unregulated capitalist system steered by a hypermasculine crew of “Masters of the Universe.” (And yes, I am making a reference to her eponymous yacht.) She knows her value lies in her, uh, personal charms and is especially inventive in deploying them to get what she wants. But from her first adulterous date with Jordan Belfort to the especially cruel moment she asks for a divorce, she never hides that she’s exactly like Belfort. That is: Her first and only true love is money itself. —Bereznak

25. Colin Sullivan (Matt Damon), The Departed

The Departed has the most acting by volume of any movie I have ever seen. Alec Baldwin applauds the Patriot Act. Martin Sheen rambles about his son at Notre Dame. DiCaprio perfects that classically bewildered expression of his. So many great bits and classic exclamations. But it’s really Damon’s slippery, slack-jawed performance as the crooked sergeant Colin Sullivan that makes The Departed such an intense cop thriller, in addition to being a great hang. —Justin Charity

24. Nicky Santoro (Joe Pesci), Casino

After Goodfellas, it was hard to imagine Joe Pesci delivering a more violent role than the Academy Award–winning work he put in as Tommy DeVito. Maybe it’s because we were prepared for it. We’d already seen Tommy murder Spider during a card game in Goodfellas; why wouldn’t I be ready for him to [checks notes] pop some schmuck’s eyeball out of his head during a brutal torture scene? But with Casino, the stakes felt higher—this was Las Vegas, full of bright lights and huge paydays in the gambling industry. Nicky Santoro, a “made” friend of Sam “Ace” Rothstein (De Niro), was organized crime pure terror turned up to the max. (Perhaps this was Pesci’s chance to go full bore, similar to De Niro’s work as Max Cady in Cape Fear.) Santoro is one of the more dangerous characters to grace a Scorsese flick: At his heart, there never seemed to be anything but rage and the desire to inflict that rage upon anyone standing in his way. And like Tommy, Nicky’s actions meant Nicky didn’t make it to the end of Casino. Only, this time, Nicky is forever remembered for the brilliant ping of a baseball bat that interrupted his inner monologue and signaled the beginning of his horrific ending. —khal

23. Howard Hughes (Leonardo DiCaprio), The Aviator

Leonardo DiCaprio had already earned his wings with his portrayal of Frank Abagnale Jr. in 2002’s Catch Me If You Can, but two years later, he followed up with an Oscar-nominated turn as Howard Hughes, the eccentric film tycoon and aviation innovator who loomed large over American culture in the first half of the 20th century. In The Aviator, DiCaprio isn’t a pathological liar and con man; he’s a full-blown eccentric who has a severe case of obsessive-compulsive disorder. No doubt DiCaprio was drawn to the challenge of this particular role, and he expertly conveys Hughes’s increasing fear with equal parts finesse and flair. —Aric Jenkins

22. Alice Hyatt (Ellen Burstyn), Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore

Right in between Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976) is 1974’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Scorsese’s anomalous romantic comedy–drama about a recently widowed mother who takes her preteen son on the road in pursuit of a singing career and a better life. At the center of it is Ellen Burstyn’s Alice, one of the most vibrant characters Scorsese’s ever put to film. She’s funny and raw and flawed, navigating abusive men and dwindling savings with equal parts wit and determination, and desperation and hopelessness. After nearly 50 years, her humor holds up beautifully. The banter between her and her smart aleck son, Tommy, is hilarious and all too real, like when an exhausted Alice breaks down in tears as Tommy explains a meandering joke that involves asking his mom whether she knows what nuts are.

Today, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore is one of Scorsese’s most underseen masterpieces, but once upon a time, Burstyn won a Best Actress Oscar for this role in one of the most stacked categories in history, beating out Faye Dunaway in Chinatown and Gena Rowlands in A Woman Under the Influence at the 47th Academy Awards. All these years later, it still feels well deserved. —Ress

21. Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino), The Irishman

The Irishman—a 10-episode miniseries masquerading as a three-and-a-half-hour movie about a labor union pension fund—is more exhilarating than any proper thriller or action movie or superhero flick from its year of Oscar eligibility. I give a great deal of the credit to Pacino, who plays the Teamsters boss Jimmy Hoffa with an immaculate irascibility that turns even the driest, tiniest grievances—“That’s what I’m doing. I’m taking traffic into account.”—into high drama. —Charity

20. Sam “Ace” Rothstein (Robert De Niro), Casino

Sam Rothstein’s favorite G.O.O.D. Fridays song is without a doubt “Christian Dior Denim Flow.” Sure, Ace knows that Kanye phones his verse in and is probably embarrassed that he knows every mush-mouthed word and hum of Kid Cudi’s part. But it’s Pusha T’s verse that Rothstein cherishes the most. When Terrence utters, “We conversate a bit about your DNA / And my salmon-colored suit from the VMAs,” electricity courses through his veins. Very few men know the pleasure, power, and protest of rocking a salmon-colored suit in front of your biggest haters, car bombs be damned.

Scorsese and De Niro imbue Rothstein with a level of sociopathic control and paranoia that’s as effortlessly slick as it is captivating. Every facet of Rothstein, from his pristine, multicolored suits to his thoughts on the correct blueberry-to-muffin ratio, is more entertaining than the bombastic realities of mob-run Vegas. The duo build up Rothstein as an all-seeing deity of the Vegas strip. He introduces the audience to the cardinal rule of this world, “The longer they play, the more they lose,” but refuses to concede that just because you run a house that always wins doesn’t mean that you do.

Rothstein, like the best Scorsese characters, is a prisoner of flimsy codes, dubious morals, and blinding hypocrisy. Ace is a pit of ego, believing he can control everything (Tangiers) and everyone (Ginger, Nicky). He plays too long and bets too much, a victim of a world and a strip that he never had as much authority over as he thought. You can only count so many blueberries for so long. —Charles Holmes

19. Donnie Azoff (Jonah Hill), The Wolf of Wall Street

I honestly don’t even know where to begin. Her father is the brother of my mom. Donnie Azoff is what you get if you cross George Costanza with Walter Sobchak. ON NEW ISSUE DAY??? THIS IS WHAT YOU DO??? Donnie Azoff is the kind of character that you always want to quote, largely because Jonah Hill’s expressions are so specific. Like, for example, the words “Oh my God, you wanna marry me? You’re in love with me?” aren’t inherently hilarious, but when they’re being said by a face so punchable that Martin Scorsese and Jon Bernthal simply couldn’t resist …?! Hill has said he was so keen to work with Scorsese on The Wolf of Wall Street that he took the union minimum, $60,000, to play the role. And we’re so blessed that he did; he makes Donnie into a guy who is somehow one of one and yet also a universal archetype of a guy. Steve Madden. Women’s shoes! —Baker

18. Jimmy Conway (Robert De Niro), Goodfellas

Henry has a reverence for Jimmy before “the Gent” even slips the kid cash upon meeting him. It’s easy to see why. Not only is Jimmy incredibly generous with his, um, earnings, but he’s also practically introduced like a superhero with the way his community adores him. Jimmy just seems like a guy who would have your back. And sometimes, he would … if you were Tommy and Henry. Others weren’t so lucky. Jimmy walked a fine line between charming and unrelenting, relaxed yet ruthlessly violent. De Niro’s portrayal of the chameleonic gangster is the high point in his decades-long collaboration with Scorsese. And just remember: Never rat on your friends, and always keep your mouth shut. —Jenkins

17. Billy Costigan Jr. (Leonardo DiCaprio), The Departed

Billy quite simply makes The Departed work. He is, at once, the film’s moral center, its doomed protagonist, and its guinea pig. Scorsese’s (and DiCaprio’s) mastery is written all over the man who has no chance of making it out clean—and this is where the creative excellence comes in—because the whole setup is filthy. Which is another way of saying that The Departed is about U.S. law enforcement and the Whitey Bulgers of the world and old-money politics. The movie isn’t known for its subtlety. In Costigan’s case, the heavy hand is warranted. —Pryor

16. Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne), After Hours

A movie like After Hours is an anomaly in Scorsese’s filmography. The film, seen by many as one of Scorsese’s more (most?) underrated, follows Paul Hackett, an otherwise dull office worker who one night decides to step out into the world in pursuit of (one evening of) happiness. Once most of his cash escapes into the busy night, it’s game on for Hackett, who is determined to reach his destination come hell or high water. All at once, every facet of ’80s New York City’s nightlife stands in the way of Hackett’s quest. The NYC that Hackett traverses may not be fire-and-brimstone hell, but the City That Never Sleeps sure feels like it in Scorsese’s viewfinder, and Dunne’s Hackett is curious, headstrong, and courageous enough to endure the chaos and stay the course—or, more important, learn to stay the fuck out of Soho. —khal

15. Sergeant Sean Dignam (Mark Wahlberg), The Departed

The best performance in Scorsese’s only Oscar-winning movie? Not even close. But the best depiction of a Bostonian ever committed to film? With all due respect to Jem Coughlin, I’ll bet you a box of Munchkins that Dignam takes that award easily. Dorchester native Mark Wahlberg’s turn in The Departed is an onslaught of dropped r’s, tough-love posturing, and hotheaded loyalty. (Plus, cinema’s most perfect use of the c-word, at least this side of the pond.) By film’s end, Dignam’s essentially a muscle-bound deus ex machina—good luck pronouncing that one in that accent—but he’s an incredibly satisfying one. He’s also the only main character to survive the movie. As such, Wahlberg once proposed a sequel focused on Dignam. If he can ever get it made, I’ll be there opening night for The Departed 2: Maybe, Maybe Not, Maybe Fuck Yourself. I need at least a few more hours to luxuriate in the way Wahlberg says cop. —Justin Sayles

14. Max Cady (Robert De Niro), Cape Fear

Scorsese and De Niro have teamed up to bring menacing antiheroes to the big screen in spectacular fashion again and again. Cape Fear’s Max Cady is a full-fledged villain and one of the most haunting figures the longtime collaborators have formed together.

A remake of the 1962 film of the same name, 1991’s Cape Fear is a brutal and relentless psychological thriller that follows De Niro’s Cady, a convicted rapist who seeks vengeance against his former lawyer after he finishes serving a 14-year prison sentence. The heavily stylized movie is like a prolonged fever dream, a tale of horror and dark humor that sees Cady become Sam Bowden’s (Nick Nolte) waking boogeyman, stalking his days and nights. There are several scenes in Cape Fear that are excruciating to sit through, including instances of gratuitous and gruesome violence toward women and Cady’s seduction of a teenage girl. And yet De Niro maintains an unnerving magnetism through all of Cady’s sickening misdeeds that makes him impossible to look away from, a truly unhinged performance that secured the actor an Oscar nomination. —Daniel Chin

13. Iris Steensma (Jodie Foster), Taxi Driver

“Didn’t you ever hear of women’s lib?” 12-year-old Iris, behind neon-green sunglasses, asks a befuddled Travis Bickle midway through Taxi Driver. She’s a smart, witty kid, but as a survivor of rape and exploitation, she’s seen, in Travis’s eyes, as a tragedy waiting to be rescued by him. As they sit in a diner, he berates her for the choices that led her out of her parents’ house and onto the street, as if the horrific abuse she experiences is her fault, and her face drops. She sprinkles sugar on her toast before she starts talking about astrology. She’s a child, but no one in the film treats her like one.

Jodie Foster establishes Iris as both precocious and naive and leads us to view the film’s brutal climactic shoot-out through her eyes. She screams and cries as blood splatters all over the brothel, only for her parents to ultimately deem Travis a hero for it. Without Foster’s layered performance, Taxi Driver’s unsettling ending wouldn’t have been nearly as impactful. —Ress

12. Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro), Mean Streets

Charismatic hothead Johnny Boy Civello first appears in Mean Streets zipping his fly, pulling up his pants, throwing his arms around the two women flanking him, and walking through a red light–filled bar—as the Rolling Stones’ “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” blares. It’s the film’s second-most famous needle drop, and also the coolest movie entrance of all time. “That’s totally how De Niro entered our consciousness,” Quentin Tarantino once said. “It’s not so much that De Niro embodies America. He embodied New York. He embodies that New York style. That New York Italian sense of coolness that, in particular, exploded in the ’70s.” —Siegel

11. Frank Costello (Jack Nicholson), The Departed

Jack Nicholson is a menace. Forget The Shining. Forget the Joker. Forget the real Whitey Bulger. Forget even Frank Costello for a second. The very thought of Jack Nicholson’s voice infiltrating my consciousness with a long-ass story about ethnic crime org dynamics in Boston is fucking terrifying. I absolutely believe that a lot of people had to die for him to be him. I absolutely believe he’d beat my broken arm with a Timberland, and I am absolutely going to stop doing coke deals with my jerk-off fucking cousin. —Charity

10. Bill the Butcher (Daniel Day-Lewis), Gangs of New York

Bill the Butcher is the reason we come back to Gangs of New York for a second, maybe third time. There’s fascinating history layered throughout Scorsese’s sprawling tale of 19th century Manhattan, but let’s face it: Daniel Day-Lewis carries this movie on his back. Day-Lewis is riveting from the jump as the depraved leader of the Confederation of American Natives. He’s completely out of control, yet frighteningly calculating. For basically the entire movie, Bill resembles a final boss in the hardest video game you know who seemingly can’t be defeated. It’s a masterclass in drama and another reminder of Daniel Day-Lewis’s immense talents as a performer. —Jenkins

9. Rupert Pupkin (Robert De Niro), The King of Comedy

The King of Comedy remains one of the most biting commentaries on celebrity worship in popular culture to this day. It was a box office flop when it was released in the U.S. in 1983, but it still stands as one of Scorsese and De Niro’s finest collaborations 40 years later.

Unlike some of the other obsessive antiheroes and villains on this list whom De Niro also portrayed, Rupert Pupkin is no killer. He doesn’t inspire the sort of visceral fear that Max Cady does with his mere physical presence; Pupkin is more unpresuming. The failed comedian is a desperate, pathetic stalker who aspires to break into the stand-up industry with a little help from his favorite comic and talk-show host, Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis), whether Jerry’s interested in giving it to him or not. (He is not.)

Even as Pupkin kidnaps his idol and negotiates his way onto Jerry’s show, he remains cordial amid his hostile demands, maintaining the trivial pleasantries of every interaction as if his extreme actions were business as usual. There’s a chilling eeriness to Pupkin’s overconfidence and delusions of grandeur as he fantasizes about his rapid rise to success and a life of fame. He imagines a world in which he’s the King of Comedy, and in the end, he gets everyone to play their parts in his envisioned production accordingly. —Chin

8. Ginger McKenna (Sharon Stone), Casino

Based on real-life showgirl and socialite Geri McGee, Ginger McKenna is a real femme fatale. She lives for money, and so she seduces men and stacks jewelry away for a rainy day. Sharon Stone—Oscar nominated for the role—makes Sam Rothstein’s immediate, time-stopping attraction to her more than credible: Ginger is gorgeous, fun, and a gifted hustler, which someone running a casino for the Mafia is bound to appreciate. But in Scorsese’s eyes, Ginger is also a woman desperate for safety and, therefore, endearing, complex, and vulnerable. Her selfishness is her way to protect herself, and although Sam’s affection for her is total, the life he offers her is a gilded cage. The breakdown of their relationship is all the more devastating because their connection feels genuine for both of them at different times: Ginger is truly moved by the new chinchilla fur coat he gives her early on because “no one has ever been so nice” to her, and Sam sincerely wanted to take care of and trust someone once in his life. But Ginger is Las Vegas itself: glittering, impressive, and even addictive, but built in a lonely desert. —Lazic

7. Fast Eddie Felson (Paul Newman), The Color of Money

Tom Cruise’s strutting, pool cue–twirling performance as Vincent is showier, but Paul Newman’s second turn as Fast Eddie, 25 years after The Hustler, is more memorable. He plays the mentor to the young shark and the old guy who’s still got it (even if he needs glasses). He also gets most of the movie’s best lines. Like this quip: “It ain’t about pool. It ain’t about sex. It ain’t about love. It’s about money. And the best is the guy with the most.” The role earned Newman his first competitive Oscar at the age of 62, one year older than Cruise is now. —Siegel

6. Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio), The Wolf of Wall Street

It is a testament to Leonardo DiCaprio’s unfailing cinematic charisma that he makes it a little hard to root against a Wall Street huckster. Jordan Belfort is not the best character in DiCaprio’s oeuvre—this may not even be his most astounding team up with Scorsese—but he’s definitely the one who has the best time. It’s a thorny challenge to inhabit the ravenous and brutish heart of free-market capitalism. Leo does it first with naivete, next with a dash of certainty, and then with a dose of debaucherous aplomb. Ten years later, it’s still salient. Villains like him aren’t fucking leaving. —Pryor

5. Karen Hill (Lorraine Bracco), Goodfellas

The template for the mob wife type, Karen Hill is more than the woman always at her husband’s side: She is Henry’s only true friend and ally throughout their time as gangsters and beyond, eventually going into the witness protection program with him once their lifestyle has caught up with them and all their supposed friends have turned against them. In many ways, Karen is a liability for Henry—for starters, she’s not Italian but Jewish, and even more importantly, she’s loud and won’t let herself be stepped on or manipulated. Yet it is precisely her gutsiness that matches so well with Henry’s impulsiveness and drive. Perhaps (paradoxically) the most convincing and sexiest couple in Scorsese’s entire filmography, Karen and Henry are terrible for each other but inseparable. Lorraine Bracco expertly navigates the amazement curdling into resentment, acceptance, and finally panic that Karen experiences throughout their perilous relationship, always underlining it with a sense of delight at the danger inherent to this way of life. Although evolving in an incredibly sexist world, Karen strives to remain master of her own destiny as much as she can, owning all the decisions that are made for her and rarely hesitating to speak her mind even when it could have dire consequences. —Lazic

4. Jake LaMotta (Robert De Niro), Raging Bull

In 1975, Robert De Niro won his first Oscar by stepping into Marlon Brando’s most famous role and giving new life to Vito Corleone. But it’s another echo of Brando that would become the defining moment of De Niro’s career. It comes in the closing moments of Raging Bull, when a washed-up Jake LaMotta sits alone in a dressing room and dispassionately recites the famous On the Waterfront monologue: the “coulda been a contender” speech. LaMotta then gets up and shadowboxes in the mirror—a tidy metaphor for his greatest opponent: himself. It’s the capstone of one of the finest acting performances in history—the end of a journey defined by controlled rage inside the ring and uncontrolled violence outside of it. Scorsese and De Niro created a murderers’ row of famous antiheroes together, but none were as haunting—as crushingly human—as this depiction of a real-life former up-and-comer turned down-and-outer. —Sayles

3. Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci), Goodfellas

It shouldn’t hurt so much when Tommy gets whacked. Joe Pesci infuses the gangster with enough sociopathy, ignorance, and rage to power a lifetime of gangster movies. He murders Billy Batts for being a disrespectful asshole, even though DeVito possesses the same quality in spades. Poor Michael Imperioli gets shot over flubbing a drink order. DeVito “jokingly” puts the fear of God in his childhood friend, Henry Hill, for the perceived slight of an ill-timed compliment. The “funny how” scene rests on Pesci’s singular ability to infuse his characters with a temper that’s always simmering, waiting for any excuse to spill over.

Every choice DeVito makes is so boneheaded as to border on cartoonish, even though he’s a lifeline to his friends. He’s the only one among them who can ever become a made man.

But what makes DeVito so fearsome is his undoing. There’s a purity about his character that’s as admirable as it is craven. He’s succumbed to this world of violence and consumption; there are no hints of Hill’s conscience or Jimmy Conway’s anxiety. DeVito was always destined to be oblivious to his execution until it was too late—a man unmade by the world that almost made him. —Holmes

2. Henry Hill (Ray Liotta), Goodfellas

Henry Hill is a walking raw deal. His character doesn’t possess the magnetic ruthlessness of Jimmy Conway or the deranged malevolence of Tommy DeVito. Instead, Hill is something more complicated and vulnerable. He introduces the audience to the intoxicating wonderland of ’60s and ’70s mob life before becoming the impetus that brings the entire operation down. Despite the voice-over, screen time, and narrative importance of the character, Hill isn’t even considered the protagonist of the film by its director.

Still, 33 years later, Hill and his grotesque humanity remain the emotional core of Goodfellas and among the most achingly realized of Scorsese’s characters. He’s a pressure cooker of ambition and contradiction, depravity and warmth. Liotta plays him like momentum incarnate, an unstoppable force hurtling to a predictable conclusion. His assured and mesmerizing voice-over pulls you into the Mafia’s singular world from that first sentence, “As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster.”

Liotta’s transcendent performance oozes out of the margins, refusing to be contained. He accelerates to soap opera hysterics then melts into documentary candidness within seconds. The force of his laughter is all-consuming and his agonized wails appear like a natural disaster.

The tragedy of Goodfellas isn’t that the rat escaped. It’s that Hill’s addiction to this life renders his sentence a purgatory. The moral code he’s etched into his soul crumbled when he needed it most. And still Hill walks out of that suburban home learning close to nothing and still wanting everything. If that isn’t the perfect Scorsese character, then I don’t know what it. —Holmes

1. Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), Taxi Driver

“You talkin’ to me?” It’s been almost 50 years since Taxi Driver dropped, and Travis Bickle remains the most terrifyingly prescient character in American film history. The army jacket. The unhinged gleam. The guns. (Who the hell gave this guy so many guns?) De Niro’s performance, with its uncanny blend of confused gentleness and awkward menace, understands how loneliness warps into paranoia and how a thwarted longing for connection warps into violence. “Someday a real rain will come and wash all the scum off the streets.” Countless Americans have followed the same path down to the same bloody fantasies since the movie was released, which makes Travis one of the rare film characters who seems to get more relevant with every passing year. Disturbing, pitiable, revolting, and absolutely essential. —Phillips