In an essay in Esquire in 2010, Martin Scorsese laid his chips on the table. “Leonardo and I have made four pictures together,” he wrote. “He is absolutely essential to me, to all of us, and essential to the history of movies.”

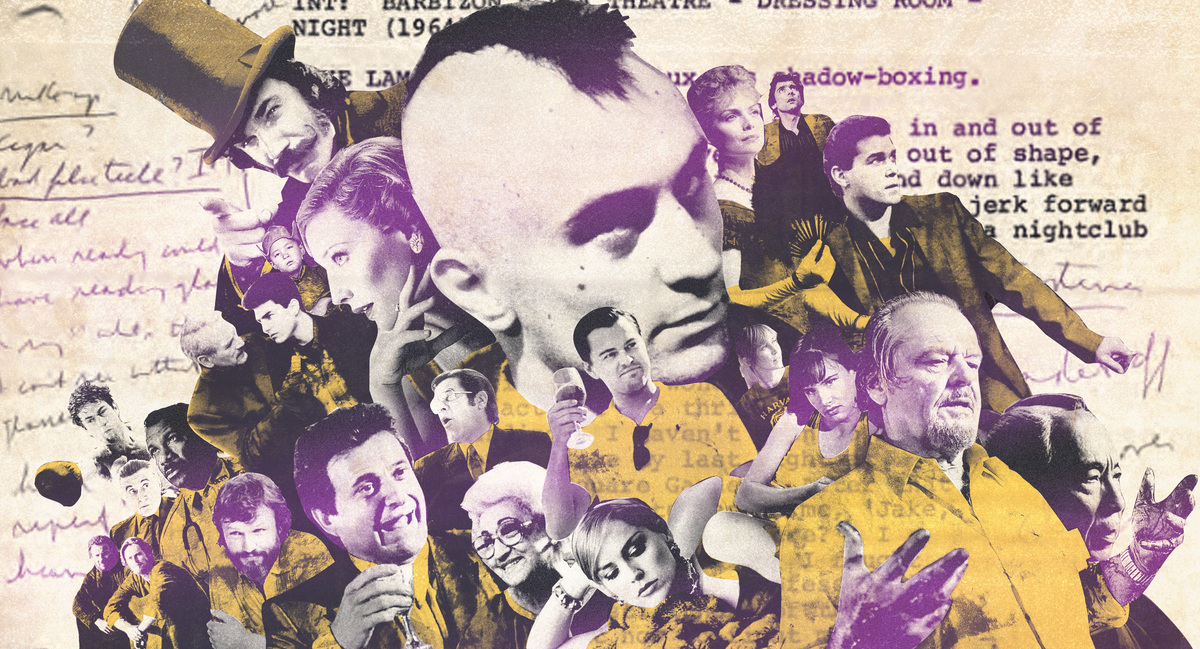

That last claim is particularly striking. Few directors in the history of movies are as conversant in the history of movies as Scorsese, whose endearing evolution from jittery ’70s movie brat to the reigning patron saint of American cinephilia (and gently begrudging TikTok icon) has always been rooted in a sense of some larger artistic narrative. Part historian, part cheerleader, and always operating with an encyclopedic frame of reference, Scorsese is more apt to celebrate than to condemn. His public pronouncements—whether they’re about the mediocrity of Marvel, the brilliance of Ari Aster, or the importance of Turner Classic Movies—bypass arrogance and register instead as benedictions. Scorsese’s lifelong affair with cinema was forged by youthful encounters with Italian neorealism and film noir—for him to even place Leonardo DiCaprio, who collaborated with Scorsese for a sixth time with Killers of the Flower Moon, in the conversation is highly noteworthy. You don’t need to be Martin Scorsese to know that Leo is a major movie star, but the question of whether he ranks among the greatest ever—or whether or not he’s essential—pivots, one way or another, on the work they’ve done together.

When Scorsese cast DiCaprio as the lead in his long-gestating epic Gangs of New York over 20 years ago, it was understood in some corners mostly as a mercenary move, a clever hedge against potential box office failure. On the page, Herbert Asbury’s 1927 nonfiction history book about the two-fisted tribal politics of a metropolis in transition was dense, heady stuff; for the movie version, Scorsese needed a headliner who could attract an audience big enough to offset the spiraling budget, so why not hit up the star of a similarly deluxe period piece that had recently broken box office records? Relentlessly violent, explicitly political, and featuring Bono’s caterwauling in lieu of Celine Dion’s, Gangs of New York was never going to be Titanic; Scorsese didn’t want to sweep audiences off their feet so much as bust them in the chops. The result is a movie with plenty of tactile brutality but little romantic spark. Cast as a hard-driving, revenge-minded orphan opposite Cameron Diaz’s nimble-fingered pickpocket, DiCaprio is considerably less charismatic as Amsterdam Vallon than he’d been for either James Cameron or Baz Luhrmann, whose swoony Romeo + Juliet keyed into the actor’s limpid beauty. It isn’t that DiCaprio lacks the skills—he’d pulled off a tricky role as an intellectually disabled teen years earlier in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape—but he seems out of place. Despite an intensive preparation process designed to make him credible as a bare-knuckle brawler type, DiCaprio projected millennial energy into a 19th-century narrative. Surrounded by a crew of calloused character actors, he almost comes off as a CGI interloper.

Where DiCaprio’s anodyne blandness works perfectly, though, is in direct counterpoint to Daniel Day-Lewis’s iceberg-sized overacting as the underworld kingpin Bill the Butcher. In the same way that the anxious, striving Amsterdam fails to hold his own against the glass-eyed killer who once took out his father, DiCaprio submerges his charisma and humbly cedes his scenes to Day-Lewis, letting the older and more daring actor dominate the film as an antiheroic master of ceremonies. Five years later, Paul Thomas Anderson would mine the same dynamic by pitting an even more unprepossessing actor, Paul Dano, against DDL. If There Will Be Blood is a better movie than Gangs of New York, it may be because it doesn’t ask us to believe that its symbolic David ever has a shot at taking down Goliath.

The reviews for Gangs of New York were mixed, and DiCaprio was shut out of the Best Actor race in favor of Day-Lewis. But Scorsese was obviously taken with his young collaborator: In a 2002 interview with Roger Ebert, he revealed that his next project was a biopic about the legendary impresario and industrialist Howard Hughes, and that he already had a star in mind. “You know who looks uncannily like young Howard Hughes?” Scorsese mused to his interlocutor. “Leonardo DiCaprio.”

If Gangs had felt like a tryout for an ascendant A-lister, The Aviator—which had begun life as a vanity production for Warren Beatty and had previously attracted potential stars from Nicolas Cage to Edward Norton to Jim Carrey—was an honest-to-goodness showcase. A sprawling, luxurious biopic, The Aviator centered on a world-historical figure whose friends and rivals alike could agree only that he contained multitudes: visionary, daredevil, narcissist, womanizer, iconoclast, recluse. “There are shape changers,” Scorsese told Vanity Fair on the eve of the movie’s release, gamely trying to throw a veil of mysticism over DiCaprio’s performance. “We found ourselves surprised at certain points of the picture when Leo would walk on the set. It was Howard, or at least it was our version of Howard ... I hadn’t seen that happen for a long time in pictures.”

Certainly, DiCaprio shows more range in The Aviator than in Gangs of New York. He’s wonderfully seductive in the early sequences, which depict the young Hughes as a larger-than-life playboy whose simultaneous mastery of two very different (and differently dangerous) vocations—film directing and plane flying—marks him as an avatar of modernity, a 20th-century boy wonder whose need for speed predates Pete Mitchell. A case can be made that some of Scorsese’s greatest movies, from Mean Streets to Raging Bull to Goodfellas, are to an extent acts of self-portraiture, and as Leo’s Hughes slowly shifts from exhilaration to obsession—consumed as much by his own artistic-industrial ambitions as by his obsessive-compulsive disorder—the performance begins to reflect Scorsese’s maximalist urges. The late sequence in which Hughes barricades himself inside a private screening room, his naked body alternately strobed in flickers of celluloid and flashes of expressionistic red light, is the stuff that tour de force performances are made of—almost to a fault, however. When Robert De Niro battered his fists and skull against a prison wall in Raging Bull, the actor was subsumed by the character; in The Aviator, the lasting impression is more of an actor striving to transcend his own celebrity.

In The Departed, DiCaprio played a modern variation on his Gangs of New York part—a tough urban foundling trying to infiltrate a criminal organization without betraying his true loyalties. The Butcher in this equation is Jack Nicholson’s flamboyant Boston gangster, Frank Costello, who takes on DiCaprio’s Billy Costigan as an heir even while his own surrogate son Colin (Matt Damon) is embedded as a mole (or is he a rat?) in the city’s police department. The Departed’s crisscrossing plotlines are derived from Andrew Lau and Alan Mak’s terrific Hong Kong thriller Infernal Affairs, in which the central undercover cop was played by Tony Leung, an actor of peerless gravitas who can convey existential angst in a glance. DiCaprio isn’t as subtle a performer, but he’s more credible as a stressed-out, pent-up interloper than he was in Gangs of New York, and he holds his own with Nicholson in a series of head-to-head confrontations that filter life-and-death intensity through dark comedy; not only does Billy have to lie in order to stay alive, but he also has to remember not to laugh.

The recent revelation that Warner Bros. wanted to franchise The Departed in the wake of its Best Picture victory explains why Scorsese switched studios immediately, with DiCaprio riding shotgun. This time, instead of remaking a modern classic, the pair waded into the murky waters of genre homage. Adapted from a novel by Dennis Lehane, Shutter Island’s spooky potboiler plot about an isolated, windswept asylum teeming with secrets gave Scorsese a chance to pay tribute to his favorite horror directors, from Val Lewton to David Lynch. Playing a decorated World War II serviceman turned U.S. marshal, on hand to locate a missing and potentially dangerous patient, DiCaprio seems weirdly miscast until his character starts losing his grip on reality. In accordance with its pulpy ethos and aesthetics, Shutter Island has a good time putting its main character through the B-movie ringer, and on one level, DiCaprio’s performance revises and improves on his work in The Aviator, shrinking Hughes’s mythic combination of grief, anxiety, and obsession down to a human scale. On another, it’s a fascinating counterpoint to his role in Inception, whose hero is similarly bewildered by a situation in which all is not as it seems.

In The Departed and Shutter Island, DiCaprio struggles and suffers: Both movies build to sick jokes in which his character is the punch line. But in The Wolf of Wall Street, he gets the last laugh as the preternaturally immoral Wall Street innovator Jordan Belfort, whose hard-sell approach made him a white-collar folk hero in the post-Reagan era. Released in 2013 to a mix of critical acclaim and social media hand-wringing over whether the film glamorized—or even endorsed—Belfort’s unscrupulous antics, The Wolf of Wall Street was not only Scorsese’s most purely entertaining movie since Goodfellas, but also probably his most politically acute. When Belfort breaks the fourth wall to address the audience directly about the details of his malfeasance, his smug complicity has a distinctly Trumpian undertone. No less than The Aviator, The Wolf of Wall Street fuses biography with allegory, but its vision of wretched excess is more convincing because it’s played for laughs: When a quaaluded-up and rubber-limbed DiCaprio tries to pour himself into a Lamborghini, the physical comedy reaches back to the silent era and beyond. It’s funny in an almost primordial way.

DiCaprio was robbed of the 2014 Best Actor Oscar by his Wolf scene partner Matthew McConaughey, whose turn as a different kind of hustler in Dallas Buyers Club was more Academy pleasing. DiCaprio eventually got his statuette a couple of years later for being mauled by a (CGI) bear in The Revenant, and he’s made only three movies since, a wind down that suggests an actor who has nothing left to prove and is willing to trust his quality control filter (which must have been broken for Don’t Look Up).

A case can be made, perhaps, that DiCaprio’s greatest performance was not for Marty, but for Quentin Tarantino in Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood, in which he slyly kidded his own narrative as an aging yet still achingly handsome matinee idol sweating his acting chops (or lack thereof). “That was the best acting I’ve ever seen in my whole life,” whispers Rick Dalton’s pint-sized costar after the old guy nails an important take on the set of the prime-time western Lancer; DiCaprio’s teary-eyed gratitude in response is hilarious because it taps into an insecurity that seems incongruous for the world’s biggest living movie star. It’s the sort of moment that makes an actor essential—and it’s doubtful that he would have ever gotten there without Scorsese in his corner for so long. “He saved me,” DiCaprio told the Deseret News during an interview to promote Shutter Island in 2010. “I was headed down a path of being one kind of actor, and he helped me become another one. The one I wanted to be.” In other words: great fucking note.

Adam Nayman is a film critic, teacher, and author based in Toronto; his book The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together is available now from Abrams.