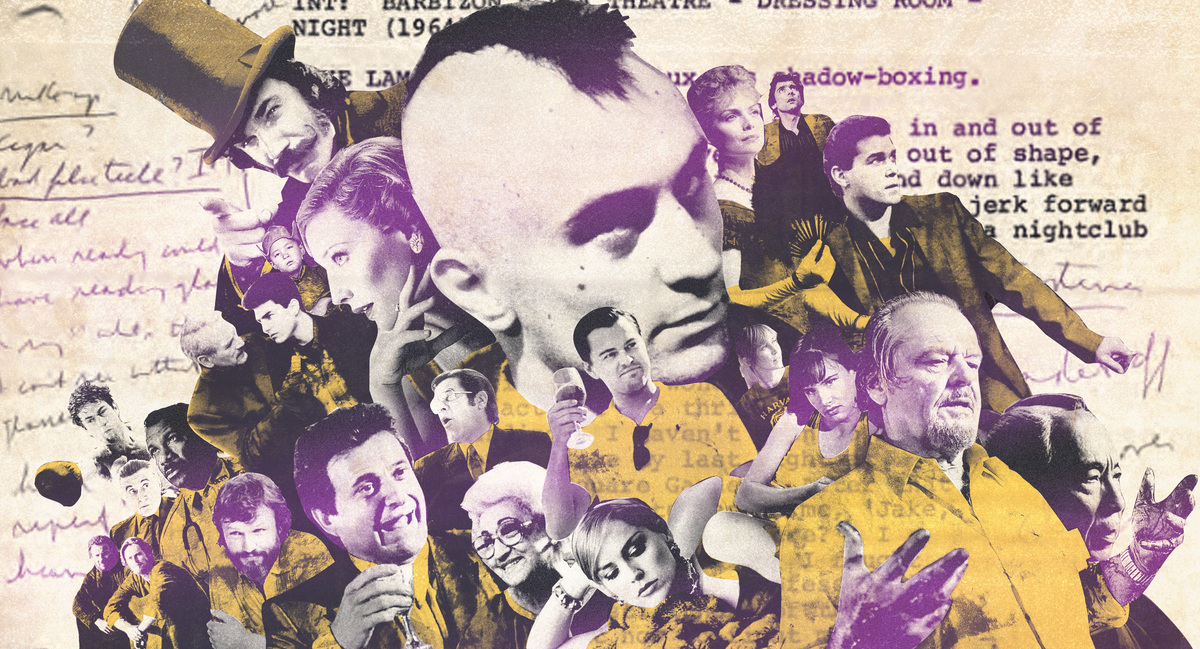

The story goes that it was finished on Christmas, but you know how tough these things can be to verify. For 15 years, Martin Scorsese had been trying to film an adaptation of The Last Temptation of Christ, a 1955 novel by the Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis. The book, which had been denounced by both the Greek Orthodox and Catholic churches—you imagine the handshake emoji extended to include elaborate robes and glimmering jewels—was given to Scorsese in 1971 by Barbara Hershey, whose eventual casting as Mary Magdalene was seemingly penciled in from the beginning, at least by her. At the time, she was starring in the director’s second film, the Roger Corman–produced Boxcar Bertha. Salaciousness was so central to that movie’s exploitation-flick, plug-and-play marketing that stills from it were repurposed for a spread in Playboy.

Scorsese optioned Kazantzakis’s novel and passed it to his friend Paul Schrader to adapt, shortly after they’d collaborated on Taxi Driver. It got set up at Paramount, with Aidan Quinn as Jesus and a budget of $14 million, and it was slated to begin filming in Israel in 1984, after The King of Comedy had been released. But budget creep and pressure from religious groups caused the studio to reconsider. The production was shut down, and Scorsese went on to film After Hours instead—in New York, on a tiny budget from independent financiers, and with a scene Scorsese lifted directly from Franz Kafka to represent his frustration over the debacle with Last Temptation and Paramount.

Four years after the aborted attempt—and with a for-hire commercial success, 1986’s The Color of Money, fresh on his résumé—Scorsese was once again ready to put Jesus on-screen. He’d convinced Universal that he could shoot it for half of what he’d budgeted for the Paramount incarnation, and he gave the studio his word that he would direct a more commercial project for them in the near future. And so he ended up in Morocco instead of Israel, with $7 million instead of $14 million, and with Willem Dafoe as the Messiah and Hershey as Mary Magdalene—and with a shooting schedule that wrapped, maddeningly, on December 25, 1987.

The director came home from the desert with committed performances from Dafoe and Hershey (and one from Harvey Keitel, playing Judas, that was so close to his contemporary New Yorker persona that it seemed avant-garde) in the can. But the conservative Christian fervor over the movie had only intensified. The televangelists swarmed; Mother Angelica, a nun with a widely disseminated talk show, called Last Temptation “a Holocaust movie” that could “destroy souls eternally.” At the Venice Film Festival, where the film premiered—more than six weeks before a Catholic group set fire to a theater in Paris that was showing the film, severely burning four attendees and injuring nine others—Scorsese was already traveling with bodyguards, insulation against the death threats that had begun to stream in. In a Venice hotel lobby, Scorsese met Ray Liotta, who approached him and his cocoon of armed men with a charismatic sense of calm. “The bodyguards moved toward him, and he had an interesting way of reacting,” Scorsese said to GQ in 2010, “which was he held his ground but made them understand he was no threat. I liked his behavior at that moment, and I saw, ‘Oh, he understands that kind of situation. That’s something you wouldn’t have to explain to him.’”

That interaction would inform, at least in part, Scorsese’s decision to cast Liotta in a career-defining role as Henry Hill in Goodfellas, the movie that would secure Scorsese some degree of carte blanche. But at the time, it was a sign of just how fraught Scorsese’s experience in the movie industry had become—and how unwilling he was to compromise the moral and thematic entanglements that had made his work so rich. Both The Color of Money and The Last Temptation of Christ are remarkable movies in a vacuum, but taken together, as mirror images or direct companions of one another, they represent the creative and commercial crossroads Scorsese had arrived at by the end of the 1980s, and they plainly articulate the spiritual tension that animates his work to this day.

The Color of Money is technically a sequel to The Hustler, the 1961 Robert Rossen film about Fast Eddie Felson, a nobody pool hustler who challenges a billiards giant. When Money was being put together in the mid-’80s, it seemed like a marketing layup, especially with Tom Cruise as the new hustler who would be mentored by Paul Newman, who was reprising his role as Felson. Both movies are based on the Walter Tevis novels of the same names; Richard Price, the celebrated New York novelist, wrote the adaptation of Color of Money. Shot by Scorsese and cinematographer Michael Ballhaus and cut by his longtime editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, the film has the verve and precision that allowed Raging Bull to move fluidly between languid domestic scenes and brutal boxing matches and The King of Comedy to seem so unnervingly like a documentary.

Set, at first, in Chicago (and shot in real pool halls and on slushy winter streets), Money follows Felson, who was effectively banished from pool halls at the end of The Hustler and became a successful liquor salesman—but whose old hustler affect gives everything he says a slight air of con-man artifice—as he grooms Vincent (Cruise) to take up his mantle.

The subtext that lurks barely beneath each quipped exchange and each slump of Felson’s shoulders are the arcs of Newman’s and Cruise’s careers. The movie-star semiotics of it all would grow tiresome if the leading men were not so immersed in the ostensible subjects of their spats in parked cars and paternal bonding sessions in cheap motels—if the pool were not so crisp and the phone calls from Felson to Helen Shaver’s Janelle were not so loaded. As Fast Eddie harangues Vincent to gain a more thorough understanding of the way his personality will read in a hostile pool hall, it’s easy to see that Newman is willing Cruise to wield his star persona in more intentional, specific ways; at several points, this is almost literalized in dialogue. The achievement of Price’s script—and of Newman’s performance (for which he was finally awarded a Best Actor Oscar)—is that this tutelage reveals more about Felson than it does about Vincent.

Complicating all of this is Carmen. Played mesmerizingly by Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, Vincent’s girlfriend, who also acts as his handler, makes it her business to always know a little more than he does. When Eddie gets Carmen alone in an attempt to gauge Vincent’s malleability, she tells him they met after she and an ex-boyfriend were arrested for burgling Vincent’s parents’ house; Carmen still wears a necklace she swiped from them. “Vince says his mother has one just like it,” she notes, smiling at the thought. “He’s sweet.” Later, she will linger, half-naked, in the mirror of a hotel bathroom to be sure Felson sees her. Felson is enraged by this and eventually shoves her against a wall—nominally because she’s complicating a potentially lucrative business arrangement, but also, the viewer is invited to suspect, because she’s baiting Felson to confront his place in a primal, ugly pecking order.

Make no mistake: This is a movie about men. While Scorsese’s filmography is sometimes glibly written off as a collection of movies exclusively for and about men, even the ones with male-dominated call sheets are usually concerned with the destruction those men leave in their wake, especially as it relates to the women in their lives. (The unspooling in the third act of Goodfellas is best distilled into the once self-possessed Karen’s terrified dash away from Jimmy Conway.) But The Color of Money is about particular, archetypally masculine anxieties: the decay of the body until it can no longer reach the same athletic heights, the inability to seduce, the inessentiality to women. This dread about aging is most thoroughly captured in the scene, one of the best-directed sequences of Scorsese’s career, where a barely postcoital Felson and Janelle answer a knock on their hotel room door to reveal Vincent and Carmen. The older couple is celebrating Eddie’s win over Vincent, but Vincent is there to drop off an envelope of cash—Felson’s cut of a winning bet on the match, which Vincent reveals he threw. Vincent is beaming, but once Carmen realizes what the news is doing to Eddie, she deflates just a bit; after those two leave, Janelle calls Vincent a “little prick” and then walks out of frame. She doesn’t offer any comfort beyond that, because there’s none to be found: It’s a near-mortal wound to Felson’s ego, his sense of self.

Felson, and the script as a whole, finds an odd spirituality in conquering this decay. Take the moment after he’s been duped by a younger, sharper hustler (a jaw-droppingly magnetic Forest Whitaker), when he’s finally fitted for eyeglasses, and the exam is set to an exultant choral arrangement—or consider the way he laments that younger players are shooting pool on speed instead of saturating themselves with liquor. “Somehow, it was more human,” he says of those days. “The Bible never said anything about amphetamines.”

We should note, first, that the evangelists were wrong. The Last Temptation of Christ—Kazantzakis’s book and Scorsese’s adaptation—is a deeply reverent work that succeeds in contextualizing Jesus’s life as one clouded by the same temptations and insecurities the rest of us face; but he triumphs over them, making his commitment to martyrdom all the more impressive and, paradoxically, all the more human. It should not be surprising that the Christian right, here and abroad, took issue with a work of art before or instead of engaging with it. And still: It’s another thing to set fire to a theater because of the way that a filmmaker considered the life of his messiah, stepped back, and muttered, “Wow.”

Dafoe’s Jesus is at first ineffectual, even a little annoying: The first time we see him interact with Mary Magdalene, she correctly pegs his solemnity as a product of his inflated self-regard, piety as a pose. This is a Jesus, after all, who is fashioning the very crosses the Romans use to crucify Jewish rebels, his supposed pacifism clarified, by Judas, as collaboration. Amid these secular concerns, Dafoe finds the delicate balance between embarrassment and conviction that would dog any person who believed they might be hearing the voice of God.

The performance does not feel out of time: Dafoe can be a wonderful, subtle physical actor, and he is so behaviorally in tune with the character that the viewer is quickly and totally immersed in the life of a carpenter, in humiliating interactions between friends, in fantasies of the mundane, and in mundane moments injected with fantastical stakes. But the voice he uses could be dubbed into Hollywood’s historical epics from decades prior without raising any suspicions. Scorsese’s shrewdest decision across the entire production was to offset this vocal performance with others that are less proper and more contemporary to the ’80s. This ensures that Jesus, human though he may be, is given to more grandiose thinking than many of his peers; it also gives color to the movie’s slyly funny scenes of local squabbles, which are allowed to remain delightfully petty rather than be saddled with the weight of parable.

But the most obvious and most important discord is between Dafoe’s Jesus and Keitel’s Judas. At different times, and in different ways, Judas is more practical and more pious than his friend: He is concerned about the way Jesus could unintentionally undermine a Jewish rebellion, but he is also insistent that Jesus must stick to the letter and spirit of messiah-dom—this is true when he refrains from killing Jesus and urges him to lead that rebellion, and it’s true at the film’s end, when he snaps Jesus out of the illusory decades of domestic normalcy with which Satan has tempted him. As in The Color of Money, there is an element to their dynamic that is typically male in the basest, most primal way. How Judas urges Jesus off his deathbed and back onto the cross is a barely concealed “You think you’re better than me?”—in large part because Keitel speaks like a barfly from outer Queens.

Beyond the sometimes stark, sometimes comic effect that Keitel’s voice has, it opens the door to a secondary reading of Last Temptation that puts it in conversation with several of Scorsese’s films. Keitel’s evocation of the so-called white ethnics who immigrated to America, especially New York, in the century leading up to the film’s release imbues several of its scenes with familiar tensions between assimilation and cultural preservation. It takes only a small leap of the imagination to transpose Judas’s hectoring to the kitchens and living rooms of the tenements in Raging Bull, in which you can always hear Italian music playing softly through the walls, or to the end of Goodfellas, with its egg noodles and ketchup. It’s an argument that a break from ancestral identity does not in fact make one an individual—it simply creates a vacuum in the soul.

That Jesus ultimately refuses the allure of quiet anonymity is a fait accompli. What was less assured was Last Temptation’s commercial viability. While it eventually grossed almost $34 million worldwide against its $7 million budget, one assumes the profit only just made up for the headache of its production and promotion. (Universal certainly did not let Scorsese out of his handshake agreement to direct something more commercial: Three years later, he would give them his remake of Cape Fear, which would gross over $180 million.) In fact, Scorsese had to return to his own creative and cultural roots to finally earn a little bit of breathing room.

In 1990, Scorsese directed, for Warner Bros., Goodfellas, a film that has been so thoroughly ingrained in pop culture that plot beats and lines of dialogue are familiar referents even to the vanishing group of people who have never seen it in full. Its loss at the Oscars is a clearer historical marker than Dances With Wolves’ win, and its formal inventiveness has been ceaselessly copied but never even passably reproduced. It did not quite double its $25 million budget during its initial theatrical run, but home video and licensing fees pushed it deep into the black years ago. If a studio, or an industry at large, wants to be taken seriously by audiences, critics, and shareholders at once, there are few better blueprints.

Scorsese basked in his newfound leverage: Cape Fear was a massively profitable lark, 1993’s The Age of Innocence was well-received and seemed to quiet the unfounded doubts about his versatility, and 1995’s Casino was a victory lap on a couple of levels—a deepening and darkening of Goodfellas’ story contours with a coda that doubles as an indictment of the changing film industry. He was out of the wilderness the ’80s had represented, seemingly for good.

And then: Kundun. Scorsese’s interest in spiritual predestiny set against secular politics is not limited to Catholicism or even Christianity at large. So it was fitting when Disney, wanting to preserve its relationship with the Chinese government, intentionally tanked the release of his film about the Dalai Lama, limiting it to just two screens on its release day—Christmas 1997, exactly 10 years after production wrapped on The Last Temptation of Christ.

In the 21st century, Scorsese has more or less been able to do what he wants, especially after The Departed approached $300 million at the box office and won him his long-overdue Best Picture and Best Director Oscars. The 2000s saw that movie, the long-gestating Gangs of New York, and The Aviator, his Howard Hughes biopic. From there, his budgets only grew—as, more often than not, did the profits. Even as the industry has faltered, he has enjoyed a sort of life-raft exceptional status: His two most recent films, 2019’s The Irishman and Killers of the Flower Moon, out this week, were astronomically expensive to produce, but the tab was picked up by tech companies (Netflix and Apple put up more than $400 million between the two films, before accounting for marketing costs).

The one lapse in this otherwise uninterrupted run of good luck—the lapse that perhaps relegates Scorsese to streamers for the remainder of his career, if the resources and marketing muscle behind The Irishman or Flower Moon can be seen as a relegation—is the 21st-century film that in some ways seemed most personal to him. Scorsese had been trying to make Silence, a story about Jesuit priests who travel to 17th-century Japan to chase their maybe-apostatized mentor, since the year after Last Temptation was released. When Silence was finally released in 2016, with Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver chasing after Liam Neeson, the film was a minor miracle: meditative but full of nervy energy, gorgeously shot by Rodrigo Prieto, and genuinely, tantalizingly ambiguous in its treatment of messiah complexes, both private and structural.

It flopped, badly. A shame for the film itself, for the reductive lessons studios took from it, and for the way it was denied its status as a fitting capstone of Scorsese’s career-long obsession with the way faith maintained and faith abandoned can both corrode the soul. And as rewarding and misunderstood as Silence is, no stretch of Scorsese’s career better captures these sorts of double binds than the back-to-back releases of The Color of Money and The Last Temptation of Christ. Resolute belief, the way men destroy themselves, and the risk that comes with estranging yourself from your roots, all Trojan horsed through a frequently hostile business apparatus. There’s something in the Bible about that.

Paul Thompson is a writer based in Los Angeles. His work has appeared in Rolling Stone, New York magazine, and GQ.