In The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, the 2013 documentary about Studio Ghibli and Hayao Miyazaki, the legendary director questions his vocation’s value. “How do we know movies are even worthwhile?” Miyazaki muses. “If you really think about it, is this not just some grand hobby? Maybe there was a time when you could make films that mattered, but now? Most of our world is rubbish.”

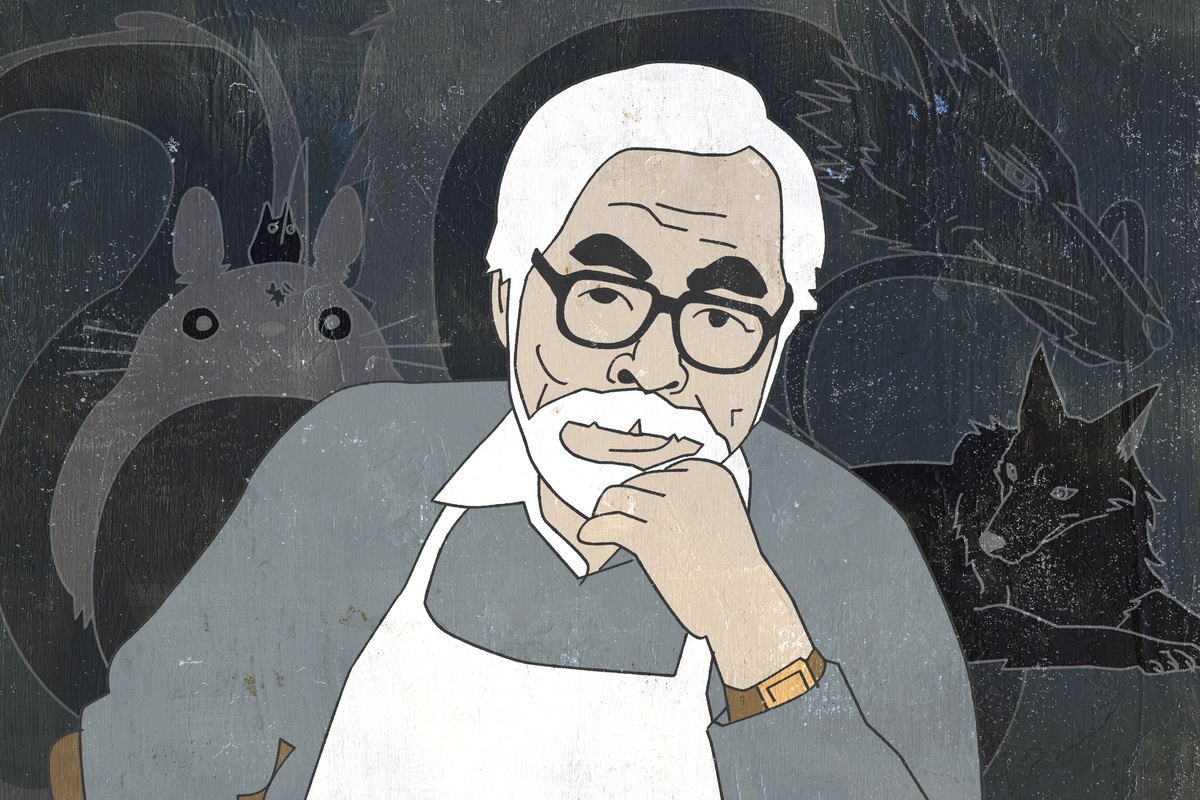

I’m not as anti–21st century as the almost-83-year-old director, but I’ll concede that there is (and always has been) plenty of rubbish around. Not enough to taint Miyazaki’s movies, though, or to prevent people from appreciating them. In fact, if there’s one thing on which audiences and critics can consistently agree, it’s that Miyazaki matters. If we quantify how often and how wholeheartedly professional and public reviewers have found his films worthwhile, relative to those of other prolific directors, then by some metrics, at least, the verdict is clear: Miyazaki’s films are the furthest thing from rubbish.

On Friday, Miyazaki’s 12th feature film, The Boy and the Heron, was released in the U.S., following its debut in Japan in July. The semi-autobiographical coming-of-age tale is alternately touching and tragic, amusing and unsettling, true to life and fantastical. And yes, it’s pretty, too. The possible swan song has gotten great reviews, boasting the fifth-highest Metascore of any film released this year. But then, that’s no surprise. It’s a Miyazaki movie.

With any other director, a 10-year gap between films on the heels of repeated “retirements” would’ve been cause for concern about whether the old guy’s still got it. But it’s hard to harbor doubts about someone who “expects perfection”—as Ghibli producer and president Toshio Suzuki put it in the 2013 doc—when he so rarely falls far short of his goal. On a House of R hype draft of anticipated 2023 titles back in January, I selected Miyazaki’s upcoming movie despite scant information on what it was about. I knew all I needed to: Miyazaki made it, and the man has never missed.

To see where Miyazaki stands among the most acclaimed directors of all time, we searched IMDb for all directors whose filmographies include a minimum of 10 features with at least 1,000 user ratings. For the resulting pool of hundreds of directors, we collected data from three sources: user ratings from IMDb and Letterboxd and Metacritic critic scores. Miyazaki might prefer that we focus on the former: In a conversation with French artist Jean Giraud (a.k.a. Moebius) in 2004, Miyazaki said, “I never read reviews. I’m not interested. But I value a lot the reactions of the spectators.” Of course, reviewers are spectators too, and everybody’s a critic, but we’ll start by looking at Letterboxd user ratings, which conveniently anoint Miyazaki as the most revered director ever.

The table below shows the highest average Letterboxd ratings (which employ a five-point scale) for features among the directors in our sample:

Top 20 Directors, Average Rating on Letterboxd

Not only does Miyazaki top the leaderboard, but he has a sizable lead. And if we sort by percentage of reviews that are five stars, he really laps the field:

Ringer head of content Sean Fennessey, who hosts The Big Picture and cohosts The Rewatchables, has been dubbed “The Lord of Letterboxd” for his heavy usage of the site. Based on that chart, though, Miyazaki may have a slightly stronger claim to the title.

“All my films are all my children,” Miyazaki has said. And he hasn’t had reason to disown any of them because the lowest rated of the bunch, his 1979 debut feature, Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro, carries a robust 4.0 rating. Some of Miyazaki’s movies have high ceilings—Spirited Away, which won an unprecedented Oscar for Best Animated Feature in 2003, is one of the 30 highest-rated features on Letterboxd—but his lofty floor as a filmmaker is even more remarkable. Virtually every other director, even the most beloved and accomplished, has had an off film or two (or four or five). But Miyazaki just hasn’t produced any duds.

Granted, Miyazaki isn’t a volume shooter—he picks his spots and takes his time. And because he worked as an animator for many years at the start of his career, often in support of fellow Ghibli cofounder and director Isao Takahata, Miyazaki’s juvenilia don’t include any feature films from before he fully honed his skills, which could have dragged his average rating down. (He was 38 when The Castle of Cagliostro came out, whereas Martin Scorsese, for instance, had just turned 25 when his first film hit theaters.) Even so, Miyazaki’s unfailingly highly rated releases are extraordinary. The standard deviation of his Letterboxd ratings is among the 10 lowest in our sample, reflecting the lack of fluctuation from film to film. Releasing films that get graded somewhere between 4.0 and 4.5 is just another manifestation of his famously rigid routine. And apart from his pace, he hasn’t slipped significantly with age.

In average IMDb user rating, Miyazaki trails only Christopher Nolan and Turkish director Ertem Eğilmez. And on Metacritic, he leads all directors who have more than 10 films with average critic ratings (a cutoff that tends to exclude non-English-language directors and inflate the ratings of Western directors from earlier eras, who are represented only by their better work).

Highest Average Metacritic Rating (Min. 10-Plus Rated Movies)

Miyazaki stands out from the company he keeps on these leaderboards in more than one way, but the most salient quality that sets him apart (aside from the animated medium he works in) may be that he makes movies for kids—or, at least, movies that kids can enjoy. Yet he’s transcended any biases against animation, kid-friendly content, and foreign-language films—in the case of the language barrier, partly by prioritizing good English dubs—to attain the highest approval rating of any director in more than one metric. These ratings and rankings underscore what we already knew: Miyazaki movies are a cinematic lingua franca, able to bridge gaps in age, taste, and nationality. As my colleague Justin Charity wrote, he’s “an unlikely hero to so many different corners of culture—cinephiles, middle schoolers, weebs.”

Miyazaki has long made movies in a fashion that’s stressful for himself and his colleagues, relying on pressure and desperation to produce inspiration. But for fans of his work, nothing could cause less anxiety than a trip to the theater to take in his latest feature because few creators across culture can be counted on to deliver like Miyazaki decade after decade, time after time. In The Boy and the Heron, an older character offers a younger one the chance to escape from our rubbish-filled reality into an artificially orderly one. But the younger character declines, choosing to return to an imperfect place. Can you blame him? Our world is often ugly, but it can be beautiful, too. For half a century or so, Miyazaki has made sure of that.