Something is wrong with the Philadelphia Eagles offense.

For the first 10 weeks of the season, nothing was wrong with the Eagles offense—or so it seemed. The Eagles were third in expected points added per drive overall. They were fourth in offensive success rate—their passing offense ranked 15th, but they were first in the run. With that pesky tush push in hand to always score in the red area, they were second only to the Dolphins in points per drive.

Since Week 11, when they came back from the bye, they’ve been terribly average: 13th in success rate, 16th in EPA per drive, 16th in points per drive. If we look at just the past three games, with losses against the Cowboys, 49ers, and Seahawks: 11th in success rate, 17th in EPA per drive, and 22nd in points per drive.

The weird thing is that it’s not clear why this downturn happened. I don’t think it was any one event—their only offensive injury was to tight end Dallas Goedert, whom they lost for three weeks, and Jalen Hurts played through an illness on Monday night—and I don’t think that the sudden stop of the Eagles offense was actually all that sudden. In fact, it’s been brewing for quite some time.

The Eagles have legit schematic issues. There are pieces of their offense that are broken, and talented players like Hurts, Goedert, Jason Kelce, and A.J. Brown have been covering up those issues for a while. Accordingly, there aren’t quick fixes waiting around the corner for Philadelphia. Sure, they’ll play better when they’re facing the Giants defense twice in the final three weeks of the regular season. But the problems they need to fix if they want to be a serious NFC contender run deep.

Initially in 2021, Nick Sirianni’s first year as the head coach of the Eagles, he was the offensive play caller. And the offense was … fine. But midseason, Sirianni gave the play-calling away to then–offensive coordinator Shane Steichen, and the Eagles offense enjoyed an immediate bump. Steichen seemed to have a better handle on play-calling, especially with his ability to find ways to maximize Hurts’s legs. By 2022, when Steichen started the season as the play caller, the entire offense was streamlined and ready to go. We all know what happened next: an MVP-caliber season for Hurts and a Super Bowl run.

Steichen is gone now and is thriving in his new job as the head coach of the Indianapolis Colts. Quarterbacks coach Brian Johnson was promoted into the offensive coordinator role and became the play caller. And even as the Eagles offense succeeded to start the season and largely looked the same, the offense didn’t feel the same. Sure, it funneled targets to Brown and DeVonta Smith and Goedert at league-leading rates as it did in 2022. Using Hurts as a rusher in short-yardage situations was the same. But something was missing. It seemed like last year, the Eagles had a real, effective, dangerous offense, and this year, they were just imitating it.

When discussing NFL offenses, we throw around the term “system” quite a lot without defining it. It’s used often as a synonym for “scheme” or “philosophy,” which is not helpful, because scheme and philosophy are two different things. So what is an offensive system?

An offensive system is a marriage of scheme (what the offense will actually do on the field) and philosophy (what the offense is trying to achieve). Consider the 49ers and Dolphins offenses, from the Kyle Shanahan system. These two offenses use pre-snap motion at league-leading rates—that’s part of the scheme, designed to create advantageous angles in the running game, get the ball to star players already on the move, and elicit pre-snap coverage tells from the defense. Philosophically, the 49ers and Dolphins offenses are predicated on making a quarterback’s decision as easy as possible; they also prioritize getting the ball to good yards-after-catch athletes in easy ways. Pre-snap motion serves those ideas, so it’s featured in the offense.

Now, consider the offense of former Steelers offensive coordinator Matt Canada. Sure, it had a lot of pre-snap motion—but the motion was often useless. The quarterback wasn’t getting handy tells about what the defense was doing, nor were easy touches created for star athletes. It was scheme for scheme’s sake—scheme without intention, with no philosophy behind it. Accordingly, while Canada’s offense imitated the Shanahan system, it was not truly of the Shanahan system.

This is an important framework to define because the Eagles don’t really have an offensive system. And that’s why things have felt different this season.

Now, it’s worth noting right away: They were very, very good on offense last year, and they didn’t really have a system then either. The 2022 Eagles ran a shockingly small number of plays from a shockingly small number of formations. It’s hard to describe this in its entirety with catchall data because formations are so varied across the league, but we can use a few cases as examples.

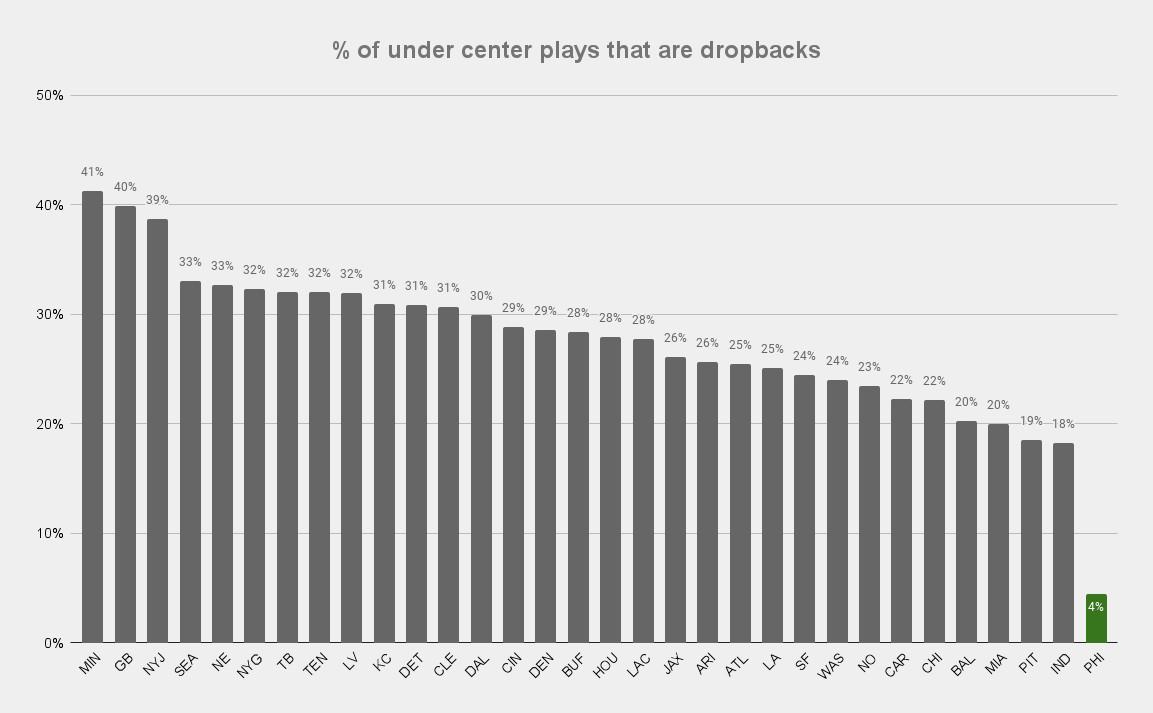

Here’s a graph showing how many passes each team has called from under center.

The Eagles don’t go under center to pass the football. They’ve done it three times this season; Hurts was sacked twice, and on the third, a deep pass to Brown fell incomplete. Hard play-action fakes from under center, a staple of modern NFL offenses, just aren’t present in the Eagles offense.

You’ll note that second to last on this list are Steichen’s Colts, who also pass from under center at a remarkably low rate. The fact that Steichen’s offense in Indianapolis looks like the offense he left behind in Philadelphia does present some argument that there is a system in play here.

The Eagles rarely went under center with Steichen and still don’t under Johnson because, at their core, they are a quarterback run team. Teams with mobile quarterbacks like to be in the gun because it creates the threat of the QB run in a way that under-center formations do not. To execute the read option, for example, and many of the schematic twists and iterations of that basic concept, the quarterback must be aligned in shotgun to read out the unblocked defender and potentially pull the football.

But this year, the Eagles aren’t actually a quarterback run team. It sounds like a silly thing to say. They’re great when Hurts sneaks the football—he tied Cam Newton for the best season of rushing touchdowns from a quarterback, with 14, on the virtue of the tush push alone. But remember: The sneak is from under center.

When we remove sneaks from the sample, only two quarterbacks have more designed rushes this season than Hurts—Lamar Jackson and Taysom Hill (who doesn’t really count). But at 5.3 yards per carry, Hurts has been one of the least effective rushing quarterbacks by yards gained. His success rate of 41 percent is below average, falling in line with Josh Dobbs and Jordan Love. This is not the profile of a dynamic rushing quarterback—one who gives the offense a good reason to line up primarily in shotgun to serve his play style.

And remember, all of that performance is on designed, non-sneak runs. By EPA per scramble, Hurts is 19th among league quarterbacks; simply on dropbacks that get outside of the pocket, Hurts is 15th by EPA per dropback. He is not a player who currently threatens defenses when he is on the move.

This is not a surprise to anyone who has closely watched the Eagles this year. Hurts is an evidently different player on the run than he was in 2022. Hurts has worn a knee brace on his left knee for much of the 2023 season, and while the Eagles have played coy with what injury Hurts may or may not have, it is clear that he does not move as fast or play through contact to nearly the same degree that he did in 2022.

So the Eagles are built, by formation, to maximize a rushing quarterback … only they don’t have one. They’re schematically trying to play 11-on-11 football, but with Hurts’s limitations, it’s really only 10.25-on-11. This is the first error—the commitment to a scheme without a good philosophy behind it. They’re behaving like a quarterback run team because they were one last year, but without a healthy Hurts to run the ball, they can’t pull it off.

But we can look to Steichen’s Colts to understand that, while Hurts’s decreased mobility has affected Philadelphia’s offense some, it cannot be the lone culprit. The Colts were an 11-on-11, shotgun quarterback run team to start the season, when über-athletic rookie QB Anthony Richardson was the starter. Since Richardson was injured in Week 5, however, backup QB Gardner Minshew has no designed, non-sneak runs on the season. However, the Colts remain almost exclusively a shotgun team.

So the Colts can justify living in gun; why can’t the Eagles? It’s because the Eagles’ extreme use of shotgun isn’t the only extreme thing about their offense.

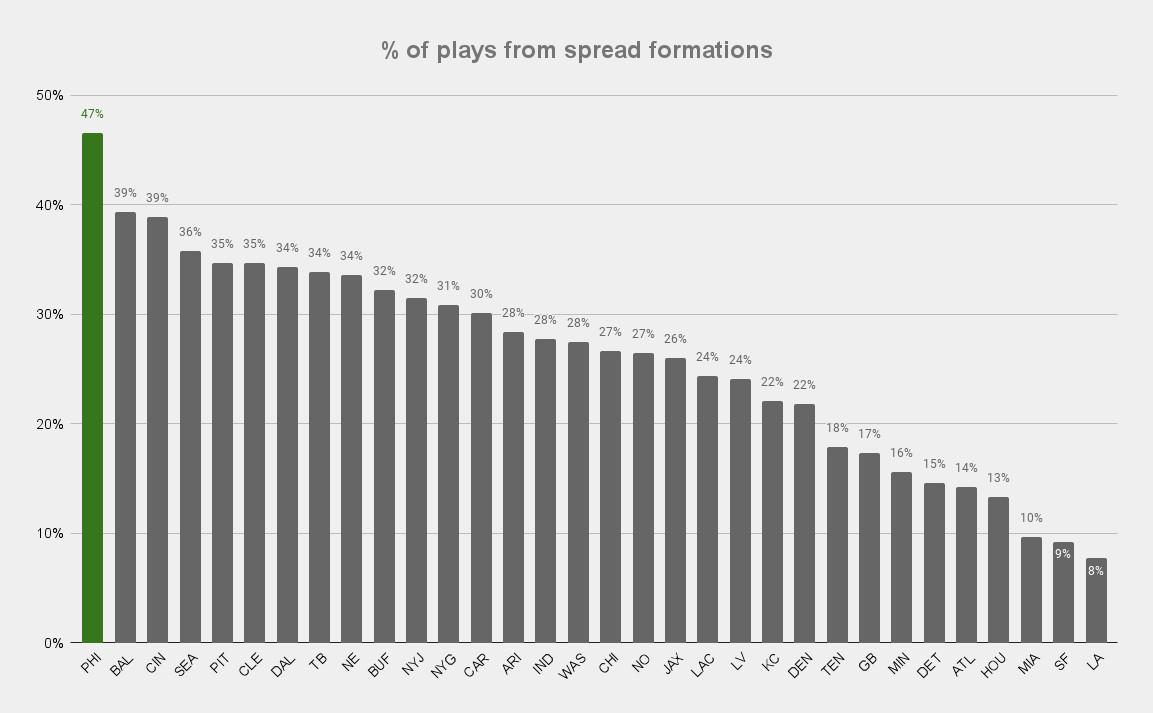

Here are all the offenses sorted by the rate at which they run spread formations (defined by Next Gen Stats’ charting, this is any formation in which the widest players—i.e., the outside receivers—are more than 30 yards apart).

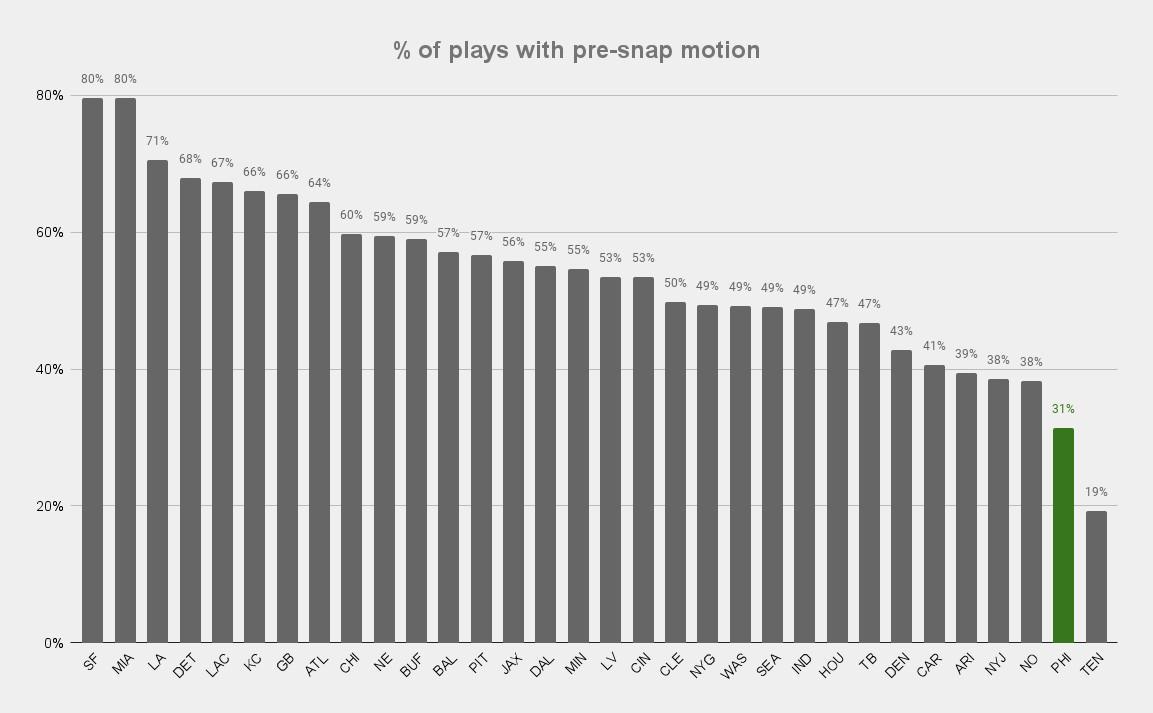

And here’s the rate of pre-snap motion this season.

I could do stuff like this all day. Among 116 receivers with at least 150 routes on the season, only nine have gotten a lower percentage of their targets from the slot than Brown; by rate of route run, only five run fewer crosses, only nine run fewer corners, and only 23 run fewer outs. Brown, one of the best receivers in the league, runs goes, slants, hitches, and in-breakers. He has a usage profile extremely similar to that of Rashod Bateman.

Perhaps even more remarkable than the rate of pre-snap motion is how much using it hurts the Eagles. Remember: Motion for motion’s sake isn’t an improvement to an offense. For every Shanahan offense, there’s a Canada offense that looks the same but isn’t nearly as productive. The Eagles are successful on 48 percent of their plays without motion and 38 percent of their plays with motion. That 10 percent drop is the largest in the league—even bigger, yes, than those Pittsburgh Steelers.

Gun, spread, no motion, simple route trees. If any of you went to a high school football game this year in your local area, that’s probably the offense you saw. It’s an offense built to force defenders into space and conflict. For example, consider what this does to a nickel corner who has both a run and pass responsibility, depending on the play the offense runs. When you spread the defense out, you’re moving the location of that player’s run responsibility (which is somewhere near the offensive line) farther away from the pass responsibility (somewhere around the wide receivers).

By keeping offensive formations static, you’re ensuring that everyone—the quarterback, receivers, offensive linemen—sees where that nickel corner is and which responsibility he is cheating toward. His conflict is obvious, and the likelihood that he can play both responsibilities diminishes. If the offense introduces a run-pass option—another thing the Eagles run significantly more frequently than the rest of the league—it can extend that corner’s conflict into the post-snap process. The quarterback can choose which play to run based on that defender’s behavior. It’s easy to make him wrong.

At least, that’s how it should work in theory. It’s much easier when that cornerback isn’t an NFL-caliber athlete and hasn’t spent the entire week studying your offense and being prepared by a cadre of NFL coaches to anticipate and solve the problems presented by your offense. And of course, this works better when an offense can meaningfully integrate the QB run. It adds even more optionality and even more conflict to the offense. The Eagles still do integrate the quarterback run—it’s just less dangerous than it was.

We can see how this is supposed to work on the Eagles’ inside-zone RPO here against the Commanders. Hurts is keying the strongside linebacker. As the offensive line moves along to run block and Hurts puts the ball in running back D’Andre Swift’s belly, he watches that linebacker. The linebacker is pulled to the run fake, so Hurts can keep the ball, set his feet to throw, and hit Brown right where that linebacker used to be.

That’s it right there; that’s the Eagles’ whole offense. When they do their nifty quarterback draw stuff, they’re doing it off of pre-snap box counts. Just like an RPO, it’s a play with multiple answers based on defensive looks: what we’d call a packaged play. Almost all of their handoffs are packaged with potential QB pulls. Everything has optionality baked into it.

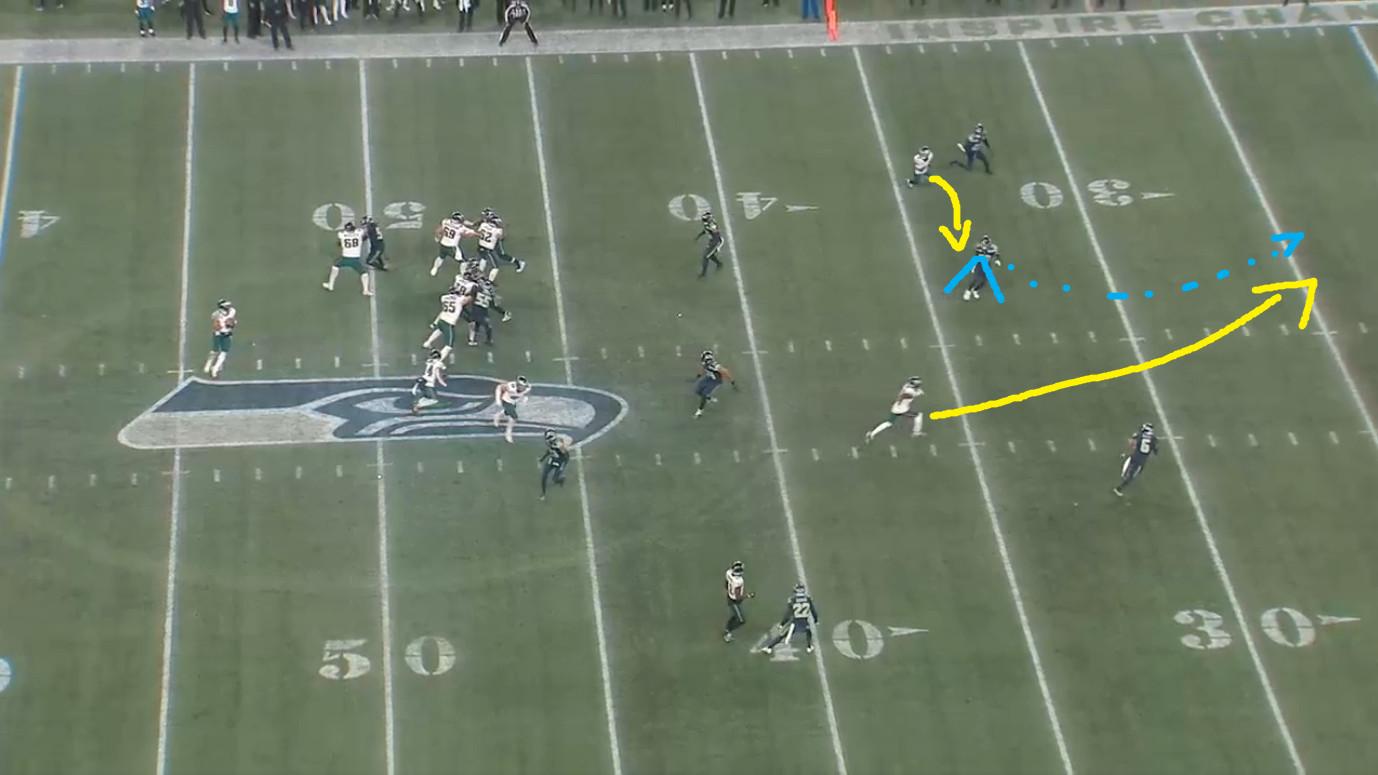

Sounds good, right? In a vacuum, sure. But the simplicity of it is starting to handicap the Eagles offense—particularly Hurts. When you live off of conditional pre-snap reads—if this, do that—you lose the ability to actually process in real time. Take this downfield shot to Brown on third-and-8 against the Seahawks. See if you can figure out where the ball should have gone (hint: it’s Smith).

How did this happen? To start, the Eagles ran some pre-snap motion, and they got the desired effect out of it! It caused some confusion in the Seahawks secondary. Cornerback Artie Burns thought he could pass the motion off to a different player, but he’s supposed to be in man coverage and was late to follow the motion across. Accordingly, when the ball is snapped and Burns becomes responsible for Smith in man coverage, he is not prepared to play coverage, and Smith runs away from him easily.

But Hurts is not accustomed to seeing motion and reading conflict. What he’s accustomed to is this: If I see man coverage, I throw the ball to Brown. And that’s not objectively wrong: Brown is an elite receiver running an out-and-up, which is a man-beating route. It is, however, situationally wrong: Hurts should have easily seen that the Seahawks were scrambling to account for the motion, known that his other star receiver was wide open as a result, and thrown it to him. That is not a hard decision to make if you are processing in real time.

Again, look at this interception to Julian Love. This play is meant to look like one of the Eagles’ RPOs, with Goedert working across the field and into the flat. Instead, it creates a downfield high-low conflict. Speed wide receiver Quez Watkins is burning on a high cross while Smith is breaking inside on a dig.

Hurts’s read is the safety, Love. Once he turns his back to Smith to chase Quez upfield, the ball should be going to Smith. It’s the same conflict that the linebacker experienced on the RPO: Once he takes the cheese one way, throw him wrong in the other direction.

But Hurts is locked in. This is a shot play, he has a speed receiver, and there’s no post safety. He’s not wrong to uncork this throw by the letter of the law; but by the spirit of the down and distance, as well as the way the play actually reads out on the field, it’s not wise to throw this.

Hurts looks like a quarterback who is not interested in or equipped to make good post-snap decisions right now. He is accustomed to pointing and shooting. In a Steichen offense that last year created great conflict for opposing defenders, and with an elite cadre of pass catchers, he could do just that: press the A.J. Brown button and pick up 15 yards. In the current Johnson offense, the Eagles are becoming even simpler and even more polarized. Their spread rates, shotgun rates, and motion rates are all more extreme this season than they were last season. They’re trying to make the easy buttons even easier, but defenses have caught up to the gag. The Eagles put Brown in the slot to run slant RPOs. They put Goedert off the ball to run split-zone RPOs. They run trips sets to run bubble screens. A simple offense eventually distills itself into easily identifiable tendencies, and when defenses are keyed in, the easy buttons vanish.

Hurts made some bad processing mistakes against the Seahawks, but he can still be a good enough processor to make a traditional dropback passing game work, especially with receivers like Brown and Smith and pass protection of the quality that his offensive line affords. Instead of taking the offense out of his hands as he struggles, you have to live through the growing pains. Put more on the field and on film. Hide tendencies not just with sneaky trick plays, but with actual new ideas. Steal from other offenses (they’ve already done this a little bit!). The Eagles need to ask their $50 million quarterback to do the things that, well, $50 million quarterbacks can and should do.

This would be a change from just running a collection of offensive plays—“Oh, this is the stuff that Steichen ran!”—to running an actual system, an offense designed and executed with intention. If the Eagles decide, philosophically, to be a QB run team with spread RPOs, that’s fine; commit to that. Get Hurts healthy and sell out for the running game. If they decide, philosophically, to play a matchup passing game that funnels targets to Brown and Smith, that’s fine; commit to that. Start putting those guys in motion, give them easy targets, and let them dominate.

But become something. The worst thing Philadelphia could do in the final stretch of the season and into January is continue doing what it has always done just because it worked in the past. It’s an offense that belongs to a coordinator who is gone, and running it isn’t working. It’s time to innovate, evolve, and improve. Or continue to be one of the league’s most disappointing offenses.