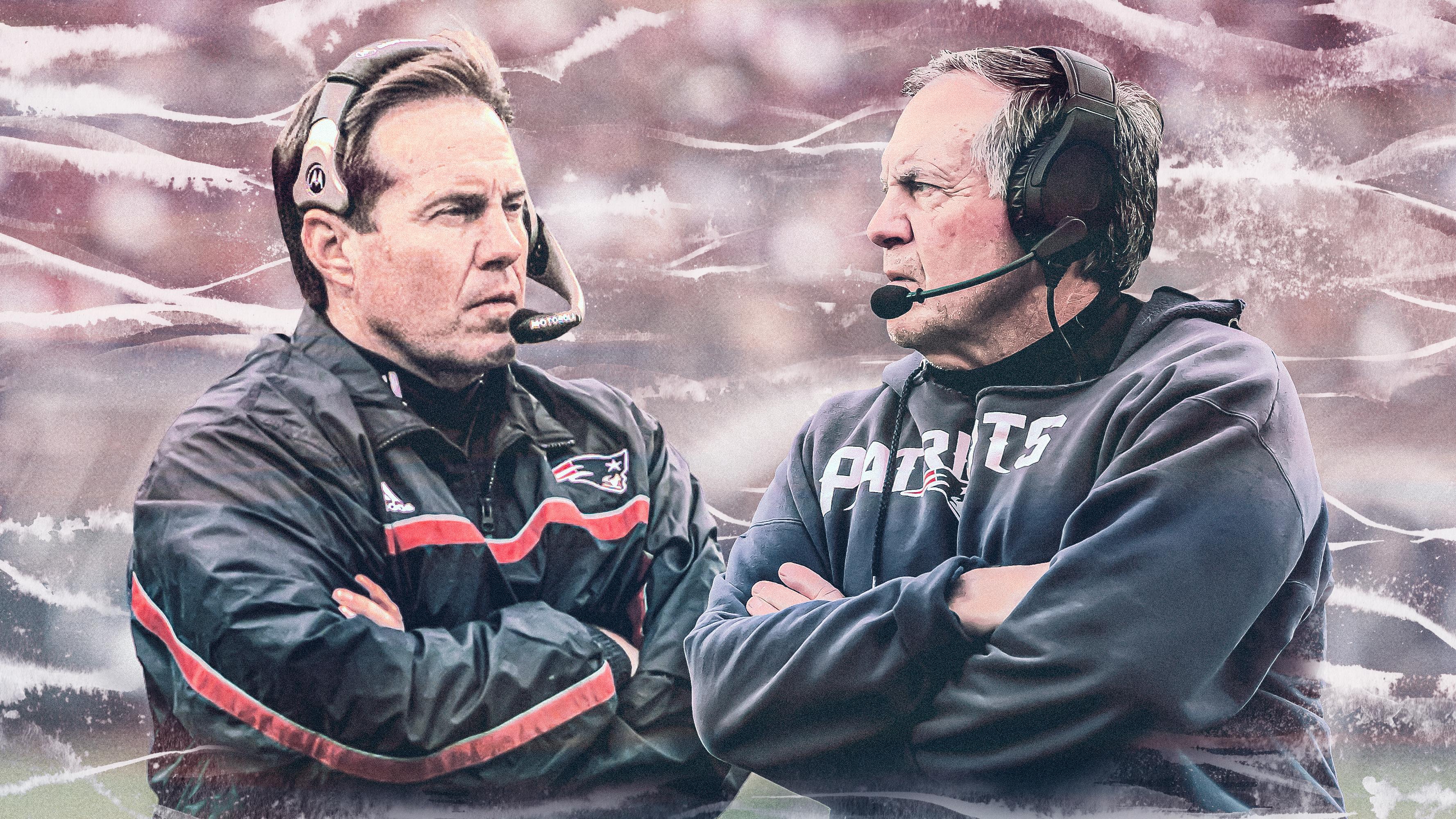

The River Finally Came for Bill Belichick

For 24 years, Bill Belichick was the Patriot Way. His legacy of the cold pursuit of winning at all costs made him the most decorated coach of all time, but in the end, it helped unravel the greatest dynasty the NFL had ever seen.Conventional wisdom said to take a timeout, but Bill Belichick never had much use for conventional wisdom.

It was nearly nine years ago, in the final minute of Super Bowl XLIX. The New England Patriots held a narrow lead, but the Seattle Seahawks were 36 inches from a seemingly inevitable touchdown. Seattle had Marshawn Lynch, after all. And all New England had was a prayer for a comeback. If only Belichick would call time.

But a curious thing happened: The Pats head coach let the seconds drain, from 60, to 50, to 40, to 30. Assistants buzzed in his headset, fans cursed at their TVs, and Al Michaels openly wondered whether Belichick would do the logical thing and stop the clock. But as was typically the case with Belichick, he saw something that no one else did. This time, it was the disarray on the Seattle sideline.

A core tenet of the Belichick coaching philosophy has been to simplify the game so that players can react, not think. Same went for himself. So as the clock ran and Seahawks head coach Pete Carroll waited for the Patriots timeout that never came, Belichick reacted to what he was seeing unfold across the field. “Something just didn’t look right,” he’d later say. “They started on, and they started off, and now, however many seconds had gone by, and I’m thinking, ‘All right, I’m not going to take them off the hook here by taking a timeout. If they want to use it, let them use it.’”

It turned out to be the perfect call—or non-call, as it were. For reasons that still sound overly complicated all these years later, Carroll went with a pass play. You know what happened next: An undrafted rookie cornerback jumped the route and intercepted Russell Wilson’s throw, ending the game and the Seahawks’ would-be dynasty in the process.

The Patriots dynasty, meanwhile, had new life. It was one of the worst decisions in Super Bowl history, coaxed out of Carroll by one of its best. And it became a signature moment for the best strategist the game had ever seen. But that sequence was also a showcase for another of Belichick’s core tenets, as best explained by his favorite general-slash-philosopher, Sun Tzu: If you wait by the river long enough, the bodies of your enemies will float by.

More than any other coach the game has ever seen, Belichick has understood that the greatest opponent isn’t the one stalking the other sideline. It’s the one staring at you in the mirror. But as the clock hits zero on this era of Patriots football, it’s become clear that this cut in both directions: The person who ultimately did Bill Belichick in wasn’t any rival or former player or league executive.

It was Bill Belichick himself.

The strangest thing about trying to memorialize the Belichick Patriots is figuring out how much winning to skip over. Does the intentional safety against the Broncos get a mention? How about the Carolina Super Bowl? Do you write a tome about the “on to Cincinnati” game or ignore it completely? Most importantly: How many pages do you dedicate to the Butt Fumble?

This is the by-product of the impossible standard set by Belichick in his 24-year run with the franchise, which came to an end Thursday when the coach and team owner Robert Kraft mutually agreed to part ways after several days of meetings this week. He made victory routine, to the point where 12-win seasons became the norm and AFC East titles became the expectation. It was a brand of excellence against which you could mark the passing of time—his tenure lasted long enough that kids born in the early years of the dynasty finished college and entered the workforce between his hiring and his exit. (That includes at least one player on the Patriots roster.)

He has six rings—or eight, if you believe his boat and count the titles he won as an assistant with the Giants—and he’s coached in more Super Bowls than Vince Lombardi coached seasons. He sits behind just Don Shula on the all-time wins list, but he did it in an era designed for parity. He not only has nine more playoff wins than the next-closest coach, but also more first-round byes than 12 franchises have total postseason victories. By any reasonable tally, Belichick is the greatest winner who’s ever coached. But that doesn’t exactly feel right when you think about what a winner looks like, does it? Where so many of his coaching peers are stars—loud and charismatic—Belichick speaks in a low mumble and gives off big history teacher energy. He’s allegedly a lot of fun when the cameras aren’t on, but when they are, he looks less like he studied the art of war, and more like he was a prisoner of it. This isn’t Tom Landry or Paul Brown—it’s a man whose old boss nicknamed him “Doom.” (He reportedly liked it because it meant he didn’t have to be nice to anyone.) The Wall Street Journal once tracked the number of times he smiled during press conferences over the course of a season. They got all the way up to seven. When you or I think of winning, we think of happiness. (I hope, at least.) But Bill Belichick finds more joy in discussing backup long snappers than he does in hoisting Lombardi Trophies. (Though make sure you ask him that one story about Pamela Anderson and the long snapper at the Pro Bowl.)

Belichick is sometimes called an enigma, and given his notorious secrecy, there’s some truth to that. But he also departs Foxborough with a remarkably simple legacy: The only thing he valued more than winning was the cold, often joyless pursuit of it.

That pursuit began in earnest when he was tapped for the Patriots head-coaching gig in 2000. But he arrived in New England something of a tarnished genius—a legendary defensive coordinator whose Super Bowl XXV game plan sits in Canton, but a failure of a head coach whose name you wouldn’t dare speak in front of Browns fans. The Patriots, meanwhile, had clawed their way from league laughingstock all the way to mediocrity in the late ’90s. (At least they had lost a Super Bowl in ’97.) But Kraft saw something in Belichick during the coach’s brief stint in Foxborough under Bill Parcells, believing Belichick was the coach who could finally turn the franchise into a winner. So he poached him from the Jets. Belichick scribbled the most infamous resignation letter in sports history, and Kraft shipped a first-rounder to New York (a price Belichick would surely never pay himself, which is both the highest praise and greatest insult I can give him). And so began the union that would define football in the 21st century.

Nobody thought much of it at the time. (Dan Shaughnessy wrote that Belichick “might be enough of a wacko to be an effective head coach,” and he was among the most positive on the hire.) But Belichick quickly went to work to remake the franchise in his image. He imported a legion of young, hungry assistant coaches, known as the 20/20s—they worked 20 hours a day and made $20,000 a year—and eschewed a traditional front office in favor of people like his most trusted confidant, Ernie Adams, the true Foxborough enigma who held the Orwellian title of football research director. Belichick quickly took ownership over everything on the football operations side: the scouting department, the strength and conditioning program, the video department, even the things that adorned the walls. (At one point, it was a few pictures and just two sayings: A Sun Tzu quote and another sign that said, “Penalties lose games.”) He had final say over the roster and had pushed the existing personnel guy out before the calendar hit June. In a matter of months, Bill Belichick had total control.

The winning, however, wouldn’t start right away. Belichick’s first season in New England mirrored his final year with the Browns: 5-11 and miles away from relevancy. That changed the next year, starting with an injury to the franchise quarterback and rise of a little-regarded backup named Tom Brady. (More on him later.) The rest of the 2001 season turned into a plot ripped from Hollywood clichés: a few miracle kicks from Adam Vinatieri, a massive bit of luck in the form of the Tuck Rule, and a showdown in the Super Bowl with a team so fearsome they were literally called the Greatest Show on Turf. New England went into that game against the Rams as two-touchdown underdogs to those big, bad bullies. After goading Mike Martz into beating himself, just like Belichick would do to Pete Carroll 13 years later, the Patriots emerged the bullies themselves.

But as the confetti fell on the Patriots’ first title, Belichick couldn’t allow himself to fully enjoy the moment. In his 2018 biography of Belichick, Ian O’Connor recounts a scene hours after the game when an assistant asked the coach a simple question: “Now what?”

“Now what?” Belichick responded, almost offended. “We win more.”

What are the hallmarks of a Bill Belichick team? For years, they wrote books about the Patriot Way—the vague, amorphous set of Belichickian principles that asked players and coaches to put the team above themselves for the sake of winning. But nobody wins, at least not at this level, without a playing style. What makes Belichick unique is that for all of his coaching greatness, it’s hard to pin down exactly what he does. Bill Walsh had the West Coast offense. Chuck Noll had the Steel Curtain, and Tom Landry is credited with inventing the 4-3 defense. Even the great young coaches of today have their trademark schemes and personnel groupings. But Belichick has long been something of a bespoke tailor, able to beat Patrick Mahomes’s Chiefs in a track meet AFC championship game and shut down Sean McVay’s Rams in a defensive slugfest in the Super Bowl two weeks later.

But the early years of the Patriots dynasty were defined by Belichick’s defense, even if there was no one trademark of those units. Sure, there were exotic blitzes and disguised coverages—ask Peyton Manning about the latter—but the only principle most people could articulate was that he took away what the other team did best. (Former Belichick assistant Rick Venturi once attributed his success with that to Bill’s greatest strength: pragmatism.) On offense, the 2007 Patriots team was the prototype for the modern NFL offense, but you get the impression that left to his own devices, Belichick would run the triple-option with a roster of converted lacrosse players.

He had all sorts of boring phrases for his approach to game-planning. Situational awareness. Complementary football. Winning on the margins. But it all amounted to looking for the slightest advantage over his opponent—small things that other coaches ignored. Before games, it came in the form of opposition research courtesy of Adams, which broke down other teams’ down-and-distance tendencies, long before the rest of the league did. (Just one of the ways the famously analytics-adverse Belichick became a hero to the advanced-metrics community.) In games, it could be as unorthodox as taking the wind in overtime or instructing his quarterback not to throw for almost an entire game, or sometimes it was as simple as double-teaming Aaron Rodgers’s receivers in unexpected ways. It didn’t always work—the words “fourth-and-2” are triggering for football fans of a certain age. But in a league where it seems like most coaches are playing not to lose rather than playing to win, Belichick was willing to take whatever his opponents and the elements gave him. (Same went for his own limitations: Give him truth serum, and he may tell you that pitching a shutout with a third-string rookie while Tom Brady was suspended was his masterpiece.) As the wins piled up, Belichick became a religion unto himself: In Bill we trust, forever and always. (He had a much more mundane mantra for it: “It is what it is.”)

Of course, winning on the margins also meant the margins of the rule book, like when the Pats manhandled the Colts receivers so viciously that Indy’s general manager, Bill Polian, complained to the league, or when Belichick dialed up a (since banned) eligible-receiver formation against the Ravens. All was fair game in his view—even cutting up a hoodie to protest the parameters of the league’s new contract with Reebok. (The Patriots, naturally, put replicas up for sale.) As former Patriots linebacker Rosevelt Colvin once told ESPN, “It’s like this with Bill: Is this the limit? OK, then let’s go to the limit.”

At times, it also pushed past that limit. For years, rumors swirled about bugs in the visitors’ locker room or stolen playbooks, and opposing teams complained about headsets cutting out—always during the most critical moments. But those were just preamble for what happened in Week 1 of the 2007 season: During a road game against the Jets, NFL security stopped a Patriots staffer who was recording the Jets signals—a clear violation of league rules. By the time the sun rose the next day, the scandal had a name: Spygate. That it came about because of a tip from Eric Mangini, a scorned former Belichick disciple, made it something of a Greek tragedy. That it involved lying and espionage made it the perfect scandal for the secretive Patriots, who had become the NFL equivalent of the Kremlin.

If you’ve made it this far into a piece on Bill Belichick’s legacy, you surely have an opinion on Spygate. But no honest accounting of his career can skip over the cheating questions, so let’s run through this quickly: Yes, stealing signs is a part of the game, though videotaping crossed the line. No, the Pats didn’t record the Rams’ Super Bowl walkthrough. Yes, the taping went on for longer than the Patriots publicly admitted to. No, Roger Goodell shouldn’t have had the evidence destroyed. Yes, the fines and the docked draft pick were harsh enough punishment. No, it probably didn’t provide much of a competitive advantage. And finally: Yes, the person who came out looking the silliest was a sitting U.S. senator.

The real question, however: Was Belichick doing anything that any other forward-thinking coach wouldn’t have done? It’s best to leave that answer to another legendary coach. “I wish I had thought to videotape signals,” Mike Shanahan is quoted telling Goodell in Seth Wickersham’s excellent history of the Patriots dynasty, It’s Better to Be Feared.

“You can’t say that Bill Belichick is a bad guy—Bill is just better at it than most are.”

OK, it’s time. Let’s talk about the greatest quarterback who’s ever played.

The debate over who gets credit for the Belichick-Brady Patriots has existed nearly as long as the dynasty itself, and it will continue long after everyone involved is dead and buried. But how do you divvy up credit for 20 years of success in a team game? Does Belichick win two titles without Brady? Zero? Does Brady even get a second contract if he gets drafted by the Bears and not the most ruthless, forward-thinking coach of his generation? Does Brady win more if Belichick gives him better receivers? You can play the what if game for every NFL player and coach who’s ever lived, but the game gets more fascinating with the most successful coach-QB combo who’s ever lived.

What Belichick unequivocally gets credit for, however, is the decision to go with Brady in the first place. Today it seems like a no-brainer, just like not calling that timeout against Seattle. But in 2001, sticking with Brady was about as far from the conventional wisdom as you could imagine. Jets linebacker Mo Lewis knocked Drew Bledsoe, the quarterback who had just signed the richest contract in league history, out of a Week 2 game, and nearly killed him in the process. Bledsoe was a no. 1 pick just a few years removed from a Pro Bowl season. He may have, in Belichick’s view, gotten comfortable and entitled, but he was still the face of a franchise that desperately needed one. Brady, meanwhile, had been the 199th pick in the draft a year earlier, who hung around only because the Pats carried four quarterbacks that year. Plus, Belichick had already experimented with benching a local legend with the Browns—I’m sure you can still find people in Northeast Ohio upset about the Bernie Kosar decision. Belichick would have been forgiven for going back to Bledsoe the second he healed.

Except, as was typically the case, Belichick saw something that no one else did. Mainly that the little-regarded backup—the kid who couldn’t beat out Drew Henson for the starting job at Michigan—also saw things that no one else did. Brady could react quickly and read defenses better than 10-year veterans. He was a sponge for whatever Belichick and offensive coordinator Charlie Weis taught him. He outworked everyone and played with a chip on his shoulder. (Which Belichick exploited, routinely dressing the quarterback down and showing his mistakes on loop in the film room, Brady’s growing celebrity be damned. As Rick Venturi told ESPN, “If he has a motivational style, I’d say that it’s constant emotional discomfort.”) And while Brady was little more than a game manager at first—the 2001 Pats finished 22nd in passing yards—he performed when it mattered. When the stakes were the highest, he elevated beyond them: Super Bowls, AFC title games, fourth-quarter deficits—nothing fazed him. He was the perfect Belichickian player: smart, tough, and willing to put the team before himself. (To the point where he may have left $100 million on the table as his coach built a perennial contender within the constraints of the salary cap and as the team’s value exploded 40 times over.)

As the dynasty evolved, so did Belichick’s approach to building the roster around Brady. His lack of sentimentality became another version of winning on the margins, buying low on players he viewed as distressed assets and shipping them out after he’d wrung all the value out of them. The guiding principle became “Better to let a player go a year too early than a year too late.” He’d trade players or cut them; later in his New England tenure, Belichick seemed to take pride in simply letting players leave in free agency and taking the compensatory pick once they were gone. (Which he’d turn around and trade for more picks.) But the list of players sacrificed at the altar of Do Your Job could double as the Patriots’ All-Decade Teams: Lawyer Milloy, Ty Law, Adam Vinatieri, Willie McGinest, Deion Branch, Mike Vrabel, Richard Seymour, Randy Moss, Logan Mankins, Vince Wilfork, Wes Welker, Chandler Jones, Stephon Gilmore. (He would’ve traded Rob Gronkowski, too, if the tight end hadn’t retired first.) But it always worked: Behind every Ty Law there was an Asante Samuel, behind every Wes Welker a Julian Edelman. Rinse and repeat, for nearly two decades of dark magic.

The one constant was Brady, who evolved in his own right. When Belichick finally gave him some receivers in the form of Moss and Welker, the Patriots broke every offensive record out there and nearly went undefeated. (That Super Bowl XLII loss to the Giants remains the rare blemish on the Belichick record that no amount of winning can wash out. It’s shocking that he let that 16-0 banner hang as long as it did.) When Belichick punted on fielding a competent defense—2011’s was the worst of the Belichick era and one of the worst in the league—Brady still had them within a Hail Mary of another title. The greatest comeback in Super Bowl history is owed partly to Kyle Shanahan steering the Falcons offense like the captain of a sinking ship, but it’s mostly because of Brady’s furious comeback. (Well, and Julian Edelman’s fingertips.) Even in their second Super Bowl matchup with the Eagles, when Belichick and Matt Patricia were too stubborn to take cornerback and Super Bowl XLIX hero Malcolm Butler off the bench, Brady threw for 500 yards. The offense never punted, and they lost to Nick Foles on the biggest stage possible.

If you give Belichick the lion’s share of the credit for the first half of the dynasty, then you have to give Brady his share for the second half. Or maybe it’s more accurate to say that the right people found each other at the right time. (That Brady also had his own ridiculous cheating scandal is maybe the truest sign that they were the perfect pair.) But if we split the credit for the success, who gets the blame for the breakup?

By all accounts, as Brady’s career stretched on and he won three MVP trophies to go with his championship rings, he grew tired of Belichick. Wickersham has laid out the ugliness a few times, but: As Brady planned to play into his mid-40s, Belichick actively planned to replace him with Jimmy Garoppolo. (Until Kraft interfered in a personnel decision for seemingly the first time in Belichick’s tenure.) As Brady marched toward every major historical passing record, Belichick still mockingly threatened to bench him for “Johnny Foxborough.” And as alternative-medicine charlatan Alex Guerrero worked his way deeper into Brady’s circle, Belichick banned him from the Gillette Stadium sideline and kicked him off the team plane—rooting out a weed before it became too entwined. (Bill could’ve been forgiven for the Guerrero situation, but probably not the others.) Belichick and Brady turned into little more than coworkers. In the 2018 season, they won another Super Bowl—again, against the Rams for a perfect bookend to their partnership—but it was clear the fire that fueled the unparalleled success had died.

The tension came to a head in 2019, the most miserable season the pair had together—when Brady looked every bit of his 42 years and the Patriots looked as vulnerable as ever. Brady had been dropping breadcrumbs for months that he was going to leave, but it’s widely believed he would’ve stayed had Belichick offered him a fair contract that offseason. Instead, Belichick looked at Brady’s performance and reasoned that no quarterback had performed that well at anywhere near that age. Better to let a player go a year too early than too late, after all. He passed and Brady signed with the Buccaneers.

It would be the rare case of Belichick going with the conventional wisdom. And it failed spectacularly.

The strangest thing about memorializing the end of the Bill Belichick Patriots was watching the press conferences.

For years, fans were accustomed to Belichick striding to the podium after a win, giving death glares to beat reporters and offering vague platitudes to his opponents. That approach had its charms during the glory days. But as the losses piled up, the misery cosplay gave way to plain misery. By the end of this season, he was left to defend his approach amid a 13-loss season: Just days before the finale against the Jets, he sounded almost conciliatory as he told reporters, “I’ve tried to go about my job the same way every week—win, lose, good years, bad years, whatever they are.” He even tried breaking out the classics recently—“We’re on to Cincinnati” replaced by “Getting ready for Kansas City,” “InstantChat” updated to “MyFace”—but they just didn’t hit the same. It’s the byproduct of the impossible standard set by 24 years of winning.

In the four seasons since Brady left, the Patriots posted a winning record just once. There was no replacement waiting in the wings, like there had been for so many positions, so many times before. New England cycled through the corpse of Cam Newton and a 35-year-old Brian Hoyer one year, and then alternated between Mac Jones and Bailey Zappe the rest. A team that once valued winning at the expense of everything began to find solace in moral victories. Brady, meanwhile, won a championship his first season in Tampa Bay and in 2021 had a reasonable case for another MVP award. This isn’t to say one person was responsible for the dynasty or that the Patriots would still be winning now if Brady had re-signed in 2020. But it’s hard not to see it as another in the long list of what ifs.

If Brady’s exit did anything, it exposed Belichick’s other mistakes. Recent draft classes have been disasters—this Athletic piece notes that the Pats haven’t re-signed a player taken in the first three rounds since Duron Harmon, whom they picked in 2013—with the first round in particular looking brutal. (It’s not just Mac Jones—they haven’t drafted an impact player in the first round since Dont’a Hightower and Chandler Jones in 2012, with Christian Gonzalez, injured during his stellar 2023 rookie season, pending.) The big free-agent splurge of 2021—itself a betrayal of Belichickian principles—brought in decent players like Matthew Judon and Hunter Henry, but also instant busts like Nelson Agholor and Jonnu Smith. The offensive line collapsed amid trades and departures, and by the end of 2023, the Pats were starting DeVante Parker, DeMario Douglas, and Tyquan Thornton at receiver. Belichick could still coach up mid-round linebackers and undrafted corners in the post-Brady era because he’s still one of the greatest defensive minds in the league, even at age 71. But the past few years have exposed just how talentless the Pats are on offense. Such is the case when you don’t have a Hall of Fame quarterback to paper over the cracks.

In the end, the ultimate game plan chameleon couldn’t adapt one last time. He refused to build out an analytics department, even after Adams retired in 2021, and as the coaching staff got brain-drained three or four times over, he kept the ranks small and insular, going as far as to bring in his sons for key spots. (In retrospect, two of his better recent hires.) When longtime assistants like Dante Scarnecchia or Josh McDaniels retired or left for other jobs, he brought in loyalists and retreads like Matt Patricia and Joe Judge. (The failure of his coaching tree in other places only underscores the fact that there was no system, only Belichick himself.) When he had a new offensive coordinator—Bill O’Brien, another retread—forced upon him by the owner this year, Belichick reportedly did everything in his power to undermine him. There was talk of infighting, assistants seizing power amid the chaos, and player insubordination. It brought to mind a quote from Belichick himself, this one from 2022: “Ultimately, it’s my responsibility, like it always is. So if it doesn’t go well, blame me.” And also another from Sun Tzu and The Art of War: If there is disturbance in the camp, the general’s authority is weak.

As rumors about his future swirled the past few months, fans began working through the Kübler-Ross stages: denial of the state of the team, anger at blowout losses, depression at the thought that the Patriots may be back where they were in early ’90s, when two-win seasons were more likely than Super Bowls. Most fans, however, got stuck on the bargaining phase: If Belichick was still a great game day coach, couldn’t the team bring in a new GM to handle all the other stuff? But it was never going to happen that way. Not for Bill Belichick, not for the way this team was run.

I keep coming back to the word “collectively.” With the seconds ticking down on his time with the Patriots, Belichick told reporters that he was “for whatever, collectively, what we as an organization decide is best for our football team.” Some thought it was a sign he’d accept a front-office change. But for decades in New England, the collective started and ended with one man. It’s impossible to imagine him going with a new structure, this late in his career, unless it was exactly what he wanted. Unless the new collective didn’t truly threaten the old one. What’s best for his team—and make no mistake, it was his team—will always be what’s also best for him.

As the books closed on another dreadful season, sentimentality had to be set aside one last time. Four days after the season ended, the coach and the franchise decided to part ways—“mutually,” as Kraft said in a news conference Thursday afternoon. The winning had stopped years ago, but the ride would stop now. Bill Belichick became the latest victim sacrificed to Do Your Job—another gone, but this one maybe a year too late. Word is he wants to continue coaching, and he’ll be on to Washington or Atlanta or whichever city makes the most sense for him to chase Shula’s record. But for the first time since the Clinton administration, it won’t be in Foxborough.

His Patriots reign outlasted almost everyone—from Parcells to Martz to Mangini to Brady to even Pete Carroll, who stepped down as Seahawks head coach on Wednesday, just a day ahead of Belichick’s departure. But eventually the river comes for all of us. Bill’s enemies were finally able to see his body float by. They just had to wait a quarter century.

But back to the press conferences. This past Sunday, after a rock-bottom loss in the snow to the team he hates most, Belichick strode to the podium at Gillette Stadium, just like he had hundreds of times before. It looked like any other week, with him standing against the same blue backdrop with the Flying Elvises, taking the same probing questions, offering the same nondescript deflections. But amid the sameness, a sense of finality hung over the proceedings—the knowing feeling that everyone watching was witnessing the end of the greatest run in pro sports history. Reporters asked the big questions about the future, as well as the suddenly inconsequential ones, like how he decided the depth chart that week. When asked when the worst season of his career had taken the wind out of his sails, Belichick offered only a pithy, solemn reply: “I still like coaching.”

Naturally, he never smiled once.