The Shanahan offense.

If you’ve watched football in the past five or six seasons, you’ve heard the phrase—you’ve likely heard it a thousand times. When Mike Shanahan was the head coach in Washington in the early 2010s, he handed the keys to the offense to his son, Kyle, and suddenly, fourth-round quarterback Kirk Cousins was a viable starter. A few years later, with Kyle in Atlanta, Falcons quarterback Matt Ryan was an MVP. Shanahan (Kyle, that is) got the 49ers head-coaching job in 2017. The rest is history.

Sean McVay, Matt LaFleur, Mike McDaniel, and Bobby Slowik were all on that Washington staff with Shanahan—they’ve sowed the seeds of the Shanahan offense far and wide. From their coaching trees have come … (takes a very deep breath) … Kevin O’Connell, Zac Taylor, Dave Canales, who are all NFL head coaches; Shane Waldron, Luke Getsy, Zac Robinson, Liam Coen, Nathaniel Hackett, Klint Kubiak, who are all offensive coordinators. Almost half of the league has a branch of the Shanahan tree on their offensive staff.

And those are just the true descendants. The success of the Shanahan system hasn’t just proliferated through coaching trees; it has also spread through imitation, as unassociated coaches have grafted Shanahan’s principles into their offenses. Ben Johnson in Detroit is running a Shanahan-style offense for Jared Goff; Kevin Stefanski in Cleveland did it for a while, before moving away this year; Drew Petzing, the Cardinals offensive coordinator who learned under Stefanski, has adopted Shanahanian characteristics as well.

But what are those characteristics? What constitutes a Shanahan offense—whether coached by an originator, by an offshoot, or by an imitator? With prolific multiplication comes evolution—each “Shanahan offense” looks a little different from the others. Intuitively, the further the offense gets away from the source, the more it should change and grow. It’s like family resemblance: The son may look just like the father, but by the great-grandson, you may see the similarity only in the eyes.

But the evolution isn’t coming only from the fringes—it is also coming from the core. Shanahan himself isn’t running “the Shanahan offense” anymore, in that “the Shanahan offense” is a static reference point, a fossilized idea, a particular scheme deployed at a particular moment. The offense that once took the league by storm, that is still taking the league by storm … the creator himself has moved beyond it.

“The Shanahan offense” is old hat. The Shanahan offense—the one that Kyle and the 2023-24 San Francisco 49ers are putting on the field every Sunday—is something new.

Let’s play a little football word association—I say an NFL phrase, you say the first idea that pops into your head. I say “Patrick Mahomes,” you say “greatest of all time.” I say “Travis Kelce,” you say “Taylor Swift.” Easy, right?

If I say “Shanahan offense,” what immediately comes to mind?

I think, for most people, the first thing that comes to mind is “play-action.” Maybe it’s “pre-snap motion” or “wide zone”—don’t worry, we’ll get to those, too.

But the play-action pass was the defining characteristic of the Shanahan offense. When Shanahan was hired, 49ers blogs wrote explainers on how the running game and passing game married up in the play-action pass. The Ringer wrote about the play-action revolution in 2017 and again in 2019, when the Rams and McVay made the Super Bowl. Heck, when the 49ers and Rams faced off in a Shanahan-McVay heavyweight fight for the NFC championship after the 2021 season, I wrote about the divergence of the two offenses. When I summarized the shared base from which they grew, I wrote: “They both won head-coaching jobs five years ago because of their wide zone, play-action pass offenses and what those offenses could do for a quarterback.”

The play-action pass received such visibility because it was sexy—oooh, big pass, many yards, how swell. Of course, Shanahan didn’t invent tagging a run fake on a passing play. But Shanahan’s investment in the running game made the play-action pass even more dangerous. Kyle, as his father, Mike, had before him, mastered the wide-zone run—and that’s what made his play-action concepts pop.

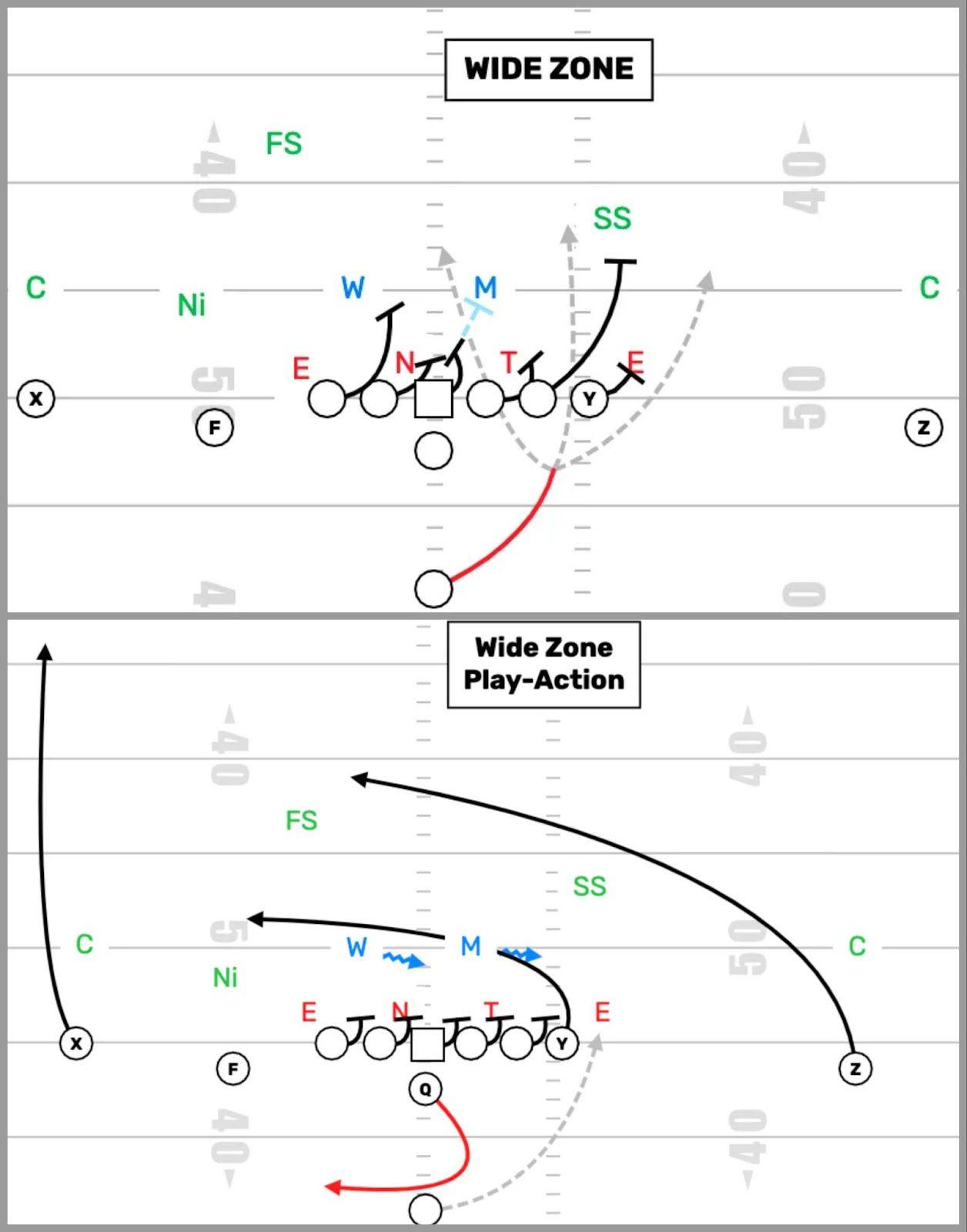

To run wide zone well, the quarterback needs to be under center—the angles and timing on wide zone don’t work well from shotgun. To run wide zone well, the offensive line needs to not just be highly athletic, but well coordinated and well coached. And to run wide zone well, the quarterback must be capable of pulling the ball on a bootleg, forcing the backside defensive end to be honest.

The play-action pass doesn’t just benefit from the wide-zone run, which yanks linebackers out of the middle of the field and forces them to flow to the sideline—it is an intuitive and necessary changeup to the wide-zone run. Wide zone pulls the defense one way; boots and rollouts pull the defense the other way; linebackers are pulled downhill by run fakes, helpless as a quick crossing route zipped into the void they just created.

The pairing is not just perfect, but symbiotic. You can’t really have your play-action dessert without eating your wide-zone veggies: the formations, the personnel, the philosophy. As McVay said on the Flying Coach podcast in 2022 with Shanahan and Peter Schrager: “This is the one thing—and Kyle and I talk so much about it—there’s a commitment to a philosophy. Everybody wants to talk about ‘Oh, marrying the run to the pass.’ But are you really committed to a system?”

But when McVay said it, he was already moving away from the system. Before the 2021 season, the Rams replaced quarterback Jared Goff with Matthew Stafford, and in doing so, McVay cast aside the offense he’d used for Goff. The Rams went under center far less and relied less on play-action passes, choosing instead to let Stafford drop back and dissect defenses from the pocket. Vestiges of the system remained—the Rams still relied heavily on pre-snap motion, and while they had weaned off of wide zone a few seasons prior, they still got under center when they wanted to run it. It worked great. The Rams won a Super Bowl.

Shanahan didn’t have such a clear inflection point as the Rams did. Of course, the 49ers have enjoyed a quarterback change with the emergence of Brock Purdy, but the changing of the Shanahan system was already well underway before the age of Brock began.

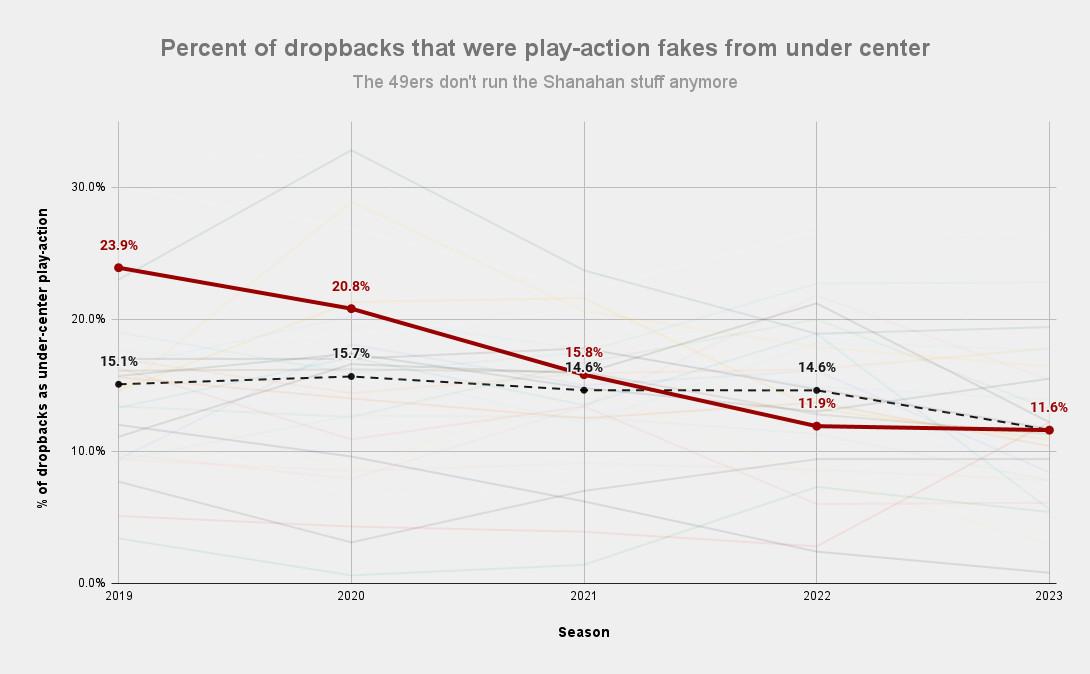

Let’s look at play-action. When we look at the percentage of passing plays that start with the quarterback under center and have a play-action fake, we can see that Shanahan’s offense has run fewer and fewer under-center, play-action fakes over the past five years (as far back as TruMedia data goes).

This is a huge drop. In 2019, one out of every four pass attempts from the 49ers came with under-center play-action attached. In 2023, it’s one out of every nine. Shanahan went from a league-leading rate in 2019 to a below-average rate in 2022.

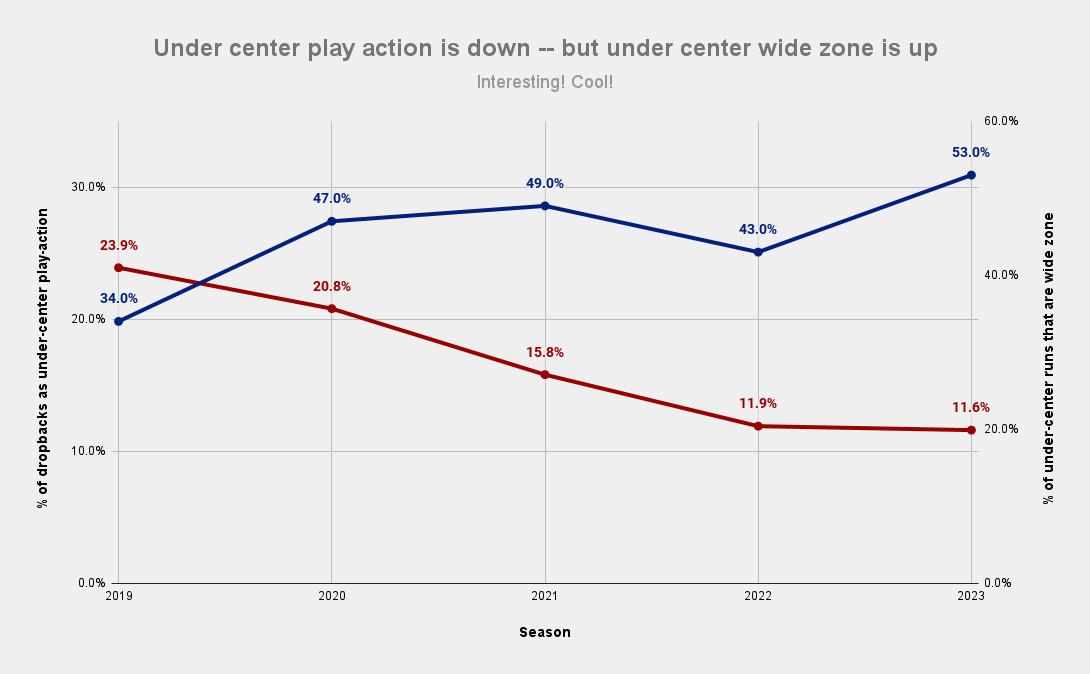

Now, remember: What defined the Shanahan system was the chemistry of the wide-zone run and the play-action pass off of it. But as under-center play-action has dropped for the 49ers, wide zone hasn’t—it’s gone up! Here’s the same graph, but with what percentage of the 49ers’ under-center runs were wide zone.

From an understanding of football based purely on data, this is not intuitive. A play-action pass, by expected points added and success rate and yards generated and any other metric you want to use, is more valuable for the offense than a handoff. Why would the 49ers discard the play-action pass—the dessert—but stay eating their wide-zone veggies?

The first potential explanation is obvious: Did defenses suddenly become better at defending play-action? I don’t think they did. By EPA per play on play-action passes, the 49ers were top five in 2019; they were top 10 in 2021; they led the league this season! By the numbers, this should be a team dialing up more and more play-action—if they had any old coach, we’d be wondering why they aren’t. But Shanahan is the king of play-action—if he isn’t running it, there’s likely a reason.

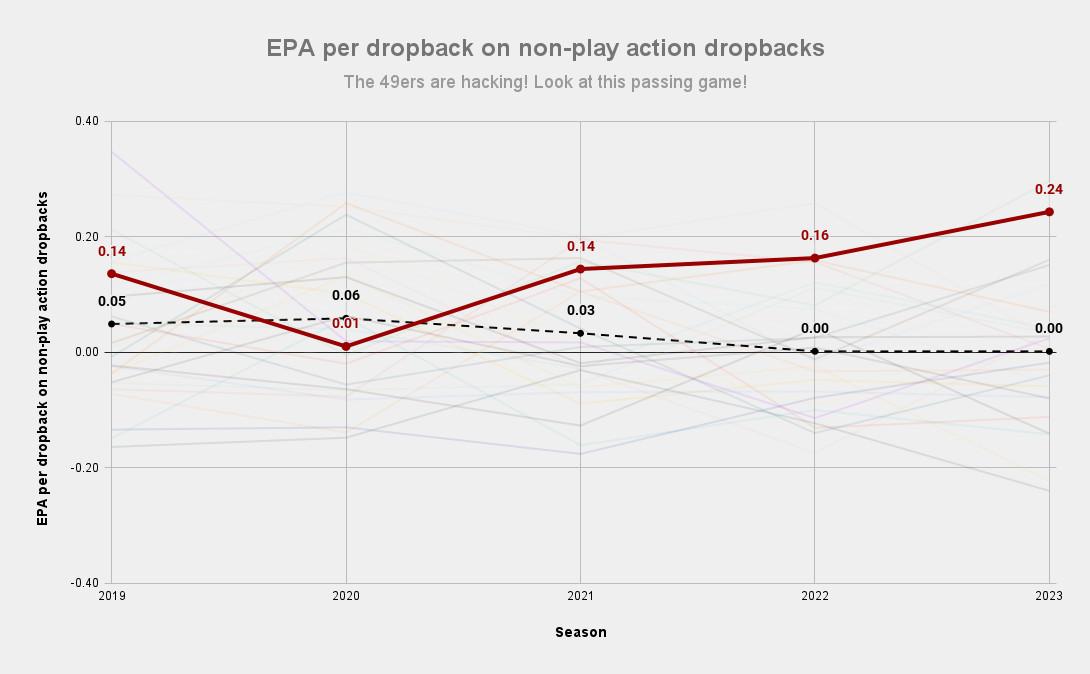

Here’s something that has changed: the 49ers have gotten far better at dropback passing. Here’s the same year-over-year look, but this time measuring EPA per dropback on non-play-action dropbacks.

The absence of play-action hasn’t left an unfilled void in the 49ers’ offensive game plan—rather, the 49ers are just dropping back without a run fake more often, and more successfully, than they have in the past. But … that’s the hardest thing for an offense to do! Play-action passing is supposed to be easier than dropback passing! Why is Shanahan going backward, swimming against the tide that he himself started?

With a new light shining on the 49ers’ approach, we’re forced to reconsider how we’ve characterized the Shanahan offense over the years. Previously, I understood play-action as the keystone of the offense—not just an integral and irreplaceable piece of the offense, but truly the piece the rest of the offense was built around. Now, I am not so sure.

To redefine how the offense works, let’s turn back to the author and hear how he understood the story. Here’s Shanahan, speaking on a podcast with Chris Simms in the summer of 2020. Simms asked him how many plays Shanahan brings into a game, recalling that he saw plans with 190 plays when he was with Jon Gruden in Tampa Bay. Shanahan brings only 30.

“It’s so different now. I might have 30 types of plays, which aren’t much. It’s a way to organize it and a way to pair them together. And a way to mix five eligibles around. I mean, if you have 30 types of concepts, and you have five eligibles between your backs, tight ends, and receivers who are somewhat interchangeable … what do those different packages give me? If I put out two tight ends, well, now, based off our studies, you’re getting these type of coverages.”

Now I think the foundation of the Shanahan offense is personnel—those five eligibles and how you use them. For Shanahan, that often means two backs: a running back and a fullback. No team used more two-back sets this season than the 49ers did. That is not some commitment to an old-school variety of smashmouth football. Rather, it’s the same logic behind play-action: Shanahan wants the defense to think that this upcoming play … might be a run.

Here’s Shanahan explaining why he uses a fullback so often to Greg Papa of NBC Sports Bay Area:

“When you have a fullback out there, that’s the only time an offense can fully dictate what’s going on. If you don’t have a fullback in there, there are certain things a defense can do where you have to throw the ball … so having a fullback always protects that. It doesn’t mean you’re gonna [run the ball], but it allows you to do it if you want to. So you don’t have to audible as much, you don’t have to change things that the defense puts you in.”

In (almost) all of the plays I’m going to show you in this piece, fullback Kyle Juszczyk is on the field. Just his presence puts the defense in a bind. It does not matter that Juszczyk lines up at tight end this season more than he ever has in his career. When he’s in the huddle, the defense must be prepared for a two-back set that can run the ball anywhere—zone strong, zone weak, power, counter, and 10,000 other iterations. They need heavy personnel in their huddle to match.

Now that Shanahan has dictated the terms of engagement with his personnel, he can run one of his 30 plays—but with a running back who can line up at receiver in Christian McCaffrey, and a wide receiver who can line up at running back in Deebo Samuel, and a fullback who can line up at tight end in Juszczyk, and a tight end who can line up at receiver in George Kittle. Those 30 plays can look like 300. Here’s Shanahan continuing on the Simms podcast.

“It’s how to run stuff that you’re good at, that your quarterback’s good at, stuff that you can always do … but you’re still attacking the defense, they don’t know what they’re gonna get. And so you got to find ways that it looks different because it is different, but your quarterback’s doing the same thing he did the first day you met him.”

There isn’t a word about “play-action” or “run fake” in any of this. That’s because a run fake is one of many ways to make plays look deceptively similar; one of many ways to put a defender in a predictable spot, then take advantage of him. Play-action wasn’t the core of Shanahan’s philosophy—it was a product of it.

Let’s put this to the film. Consider this Deebo reception from 2021, with Jimmy Garoppolo at quarterback:

This is a play-action pass concept—at least, it has been for many years in the Shanahan offense. It’s called drift—an in-breaking dig route—and it is the prototypical Shanahan concept. Everyone who runs this offense runs this concept, and everyone who doesn’t run this offense has stolen it at least a few times. It always works because of the play-action fake: the fake pulls the linebackers into the line of scrimmage, and the throw arrives behind them. Look at how Garoppolo lands on his back foot and drives this sucker with timing.

Here’s drift as the 49ers ran it against the Lions in the NFC championship game:

On this play, there is no play-action fake. Instead, the 49ers get into an apparent run formation—under center, with Juszczyk and McCaffrey both in the backfield. This formation alone forces the Lions to put five players on the line of scrimmage, as a four-down front will almost certainly lose to the run. Instead of using a run fake to pull the linebackers down into the line of scrimmage, the 49ers instead use the McCaffrey motion to pull a linebacker over to the sideline, away from the middle of the field; by keeping the tight end and fullback in to block and chip, the linebackers responsible for them in coverage are also pulled down and away from the dig window.

And finally, the critical value: because Purdy doesn’t have to turn his back to execute a play-action fake, he can see the entire play develop. The timing doesn’t have to be as perfect, because the quarterback’s eyes are always to the play. When pressure suddenly appears up the interior, he can see it coming and react in time to deliver an accurate throw to Samuel.

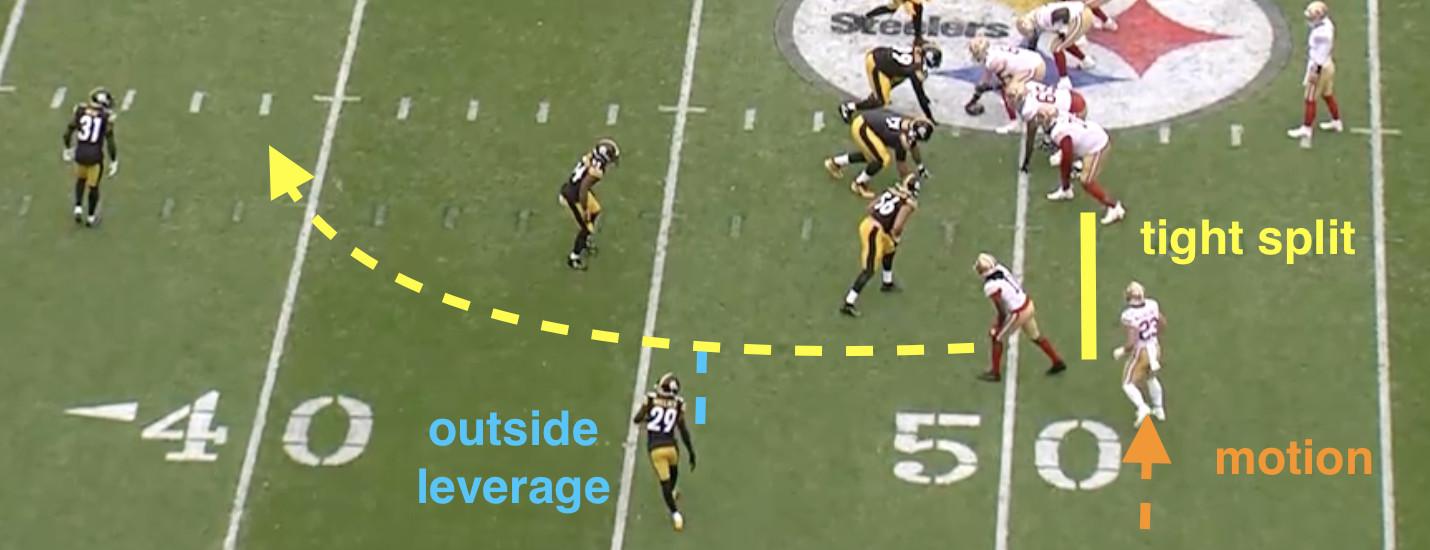

We can find plenty of examples of the 49ers getting to traditional play-action concepts without the titular play-action fake. They just create a run threat through formation and personnel. Here’s dagger, a concept you can run with and without a play fake, but that the 49ers have typically liked off of play-action. Against the Steelers this year, the 49ers just bump McCaffrey over in the backfield, and LB Cole Holcomb is drawn by his gravity at the snap. He can’t get back to the dig in time.

Here’s another concept the 49ers used to love off of a play-action fake: a bang-8 post (think a post route, but meant to be hit faster and earlier than a traditional deep post). Instead of actually presenting a run fake post-snap, the 2023 49ers threaten a run with Juszczyk in the huddle, but go for a spread formation that eventually motions into an empty formation, and hit the void in the middle of the field anyway. Watch how the seam occupies the same Tampa-2 middle linebacker that couldn’t find the Deebo dig on the play previously.

If a play-action fake manipulates the coverage post-snap, then motion into and out of the backfield can manipulate the coverage pre-snap, making the job even easier on the quarterback. Here’s Shanahan again from that 2020 podcast with Simms: “But you can change that in so many ways with how you deploy guys, whether you do it from wide splits, stack splits, you can have a way to be in three-by-one but run the same play the next week out of two-by-two just in how use your back.”

Watch that Steelers rep again. See how McCaffrey’s motion into the formation creates a very tight stack—McCaffrey and Brandon Aiyuk tight to the offensive line? Because the receivers have so much space to the sideline, the cornerback—the outermost defender—inherently has to play with outside leverage. He has help to the inside, and none to the outside—he must play with outside leverage. That makes the in-breaker that much easier.

This is another feature of the Shanahan offense that, unlike the play-action pass, has stood the test of time: formational width. According to Next Gen Stats, the 49ers offense have been top five in condensed formation rate in every season since 2017. Put another way: Nobody consistently runs tighter formations than the 49ers. This year, they average formations that are 19.9 yards wide—the lowest number in the database’s history.

Tight formations create predictable coverages. Because wide receivers are so close to the formation, they can more readily get involved in run blocking. Accordingly, safeties have to get into the box and defend the run. Defenses are forced to deploy single-high coverages to get that additional box safety—and with single-high coverages come isolated outside corners playing with that outside leverage. When you know what the safety shell is going to be, and you know the leverage of the corner, and you know both of these things pre-snap? Man, does hitting those in-breakers get easier.

All that is just alignment—we haven’t even gotten to personnel yet. When the 49ers had run-of-the-mill wide-zone backs, they couldn’t use that fifth player as a receiving threat. Now, with McCaffrey in the mix, the 49ers can line up with those tight splits … but still run concepts traditionally run from spread, empty formations. The receiving ability of McCaffrey helps them in two ways: They can run him on routes that typical backs can’t handle, and they can use his gravity to create more space in other areas of the field.

Let’s start with this deep shot against the Eagles. McCaffrey bumps out of the backfield in what the 49ers call “bumper” motion—as Shanahan described it, it allows them to run plays from an empty formation without giving the defense time and opportunity to audible to an empty coverage. McCaffrey has an option route here on the linebacker—he can break outside, or break inside. Most offenses have some sort of “weak option” concept for their slot receiver or running back—but few also allow their running back to break upfield on a vertical route. With McCaffrey, the 49ers are free to do this.

Here’s another bumper motion into an option route from McCaffrey—this time, the Eagles bracket him with two defenders, taking away his options. But the extra personnel dedicated to McCaffrey leave the intermediate middle of the field without a robber safety, and Jauan Jennings takes an easy pitch-and-catch for an explosive gain.

Just as we saw above, when the 49ers want to get to traditional play-action concepts, they can use McCaffrey’s gravity instead of faking a handoff. The 49ers walk out in 21 personnel here—a fullback and a running back, along with a tight end—and initially line up in the pistol. But with McCaffrey’s motion, they can yank LB Ernest Jones away from the middle of the field, and once again hit a dig route—this time to Aiyuk.

Much like “condensed formation” could serve as a good new moniker for the Shanahan offense, these plays show why “pre-snap motion” is also a tempting explanation. Heck—maybe it’s just “fullback.” But in reality, there isn’t just one code word, one magic spell to summon the Shanahan system. As the man himself said, there are so many ways you can change your presentation—personnel, motion, splits, alignment—that there isn’t one immutable characteristic of the offense. It’s not play-action, it’s not pre-snap motion, it’s not condensed formation, it’s not wide zone, it’s not the fullback. Sure, it feels right now like the Shanahan offense needs tight splits—but maybe, in three years, I’ll be writing about how they’re using spread formations. Right now it feels like they need 21 personnel, but what if defenses start to treat that as passing personnel? What if they start running it out of 11 personnel?

Everything is on the table. Because the keystone of the 49ers offense isn’t any one thing. The keystone of the 49ers offense is that you think it’s one thing, and it turns out it’s something else. It’s putting a fullback on the field to make you think run, so that they can pass. It’s bringing wide receivers tight to the formation, so you think of out-breaking routes, so they can run in-breaking routes. It’s motioning to a formation that you don’t think is empty, but actually is. The keystone of the 49ers offense is your perpetual wrongness. Shanahan better. Skill issue.

As Shanahan tries again to win a Super Bowl—the one accomplishment that has eluded him for so long—he is not one figure but two. He is the offensive innovator, the tastemaker, the man responsible for the state of offensive football today. The Shanahan that looks backward. But he is also the offensive innovator who looks forward, who remains on the cutting edge, ahead of the curve he drew. This Shanahan is not your momma’s Shanahan. This offense is not the offense we saw in that 2020 Super Bowl. Will it succeed where that offense fell short? We’ll find out on Sunday.