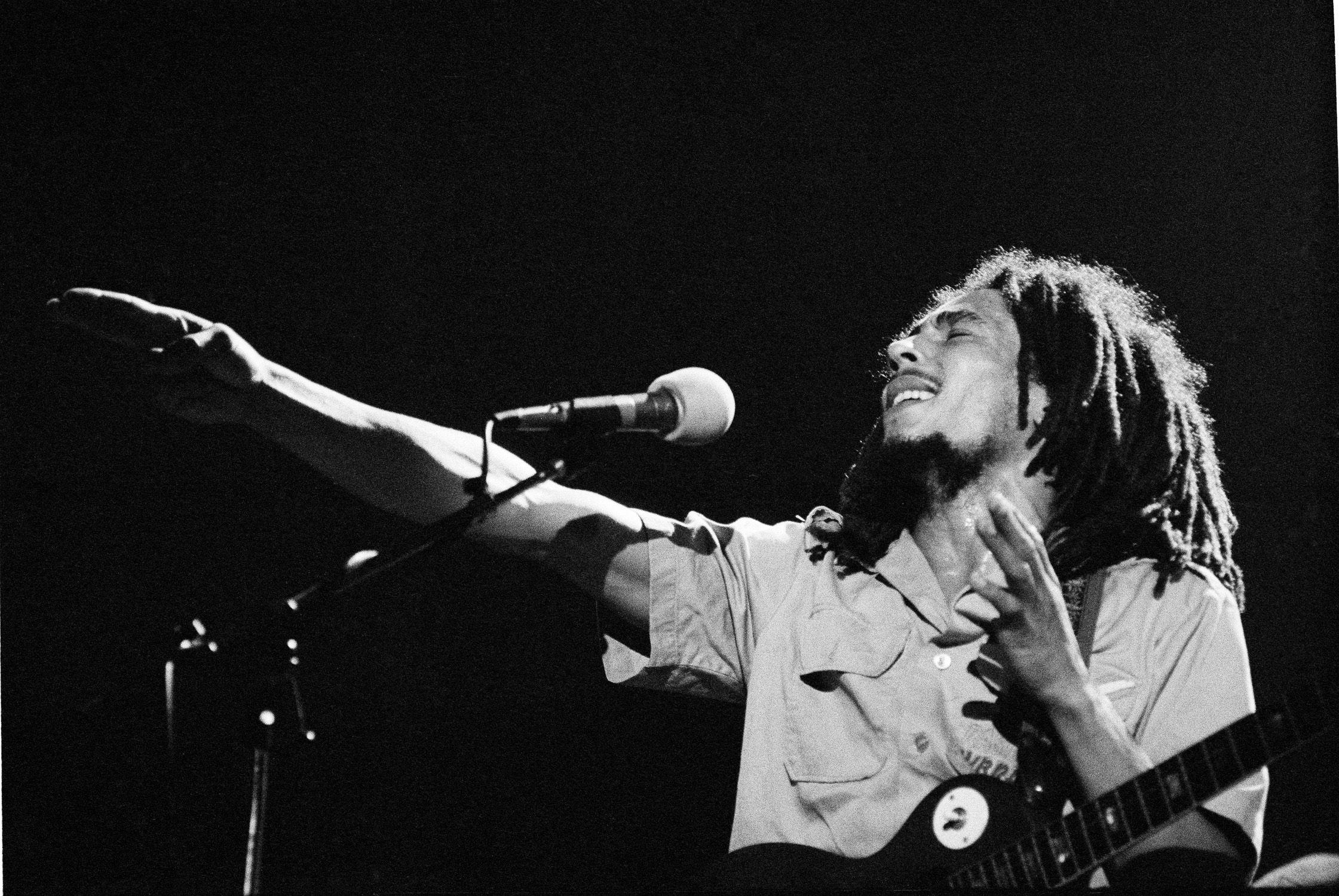

On paper, Dave Robinson doesn’t seem like the type of guy who’d be devoted to something as decidedly un–rock ’n’ roll as market research. In the 1960s, the Irish-born music lover photographed the Beatles at the Cavern Club and tour-managed the Jimi Hendrix Experience. In the 1970s, he cofounded Stiff Records, the independent British label behind early releases from Elvis Costello, the Damned, and Nick Lowe. In the early days of music videos, he directed clips for Madness and a pre-sketch-comedy star Tracey Ullman. Then in 1983, Chris Blackwell convinced him to become the president of Island Records. Robinson says that what Blackwell didn’t tell him was how bad of a financial predicament Island was actually in. He almost left the job straight away when he found out, but as a big fan of Bob Marley, one of the label’s defining acts, he was excited about getting to put together a greatest hits collection for the recently deceased singer. Blackwell gave Robinson a running order of the songs that he thought should be on it and a picture of Marley with his dreadlocks flying around his head that he thought should be the album cover.

“I’m a fairly brash individual,” Robinson recalled during a recent Zoom interview. “I said, ‘Well, if you’ve worked it out already, I don’t need to think about it because doing a greatest hits by committee is not my idea of how it works. So you do it or I’ll do it.’” Robinson ended up being the one who did it.

The result was Legend: The Best of Bob Marley and the Wailers. As it approaches its 40th anniversary this May, it’s estimated that over 25 million copies of the album have been sold—putting it among the top 20 biggest sellers of all time. That’s not counting the other millions of bootlegs, dubbed tapes, and burned CDs that have proliferated around the world. As of this writing, it has spent 821 nonconsecutive weeks on the Billboard 200 albums chart (a figure second only to Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon), and it currently sits at no. 38. Released three years after Marley’s death at the age of 36 from cancer, it was Legend that truly turned Jamaica’s biggest artist of all time into a global superstar—one who is the subject of the Paramount biopic Bob Marley: One Love, in theaters on Wednesday. Decades on, the story that Legend tells about Marley continues to shape his legacy. But for some, it’s still not telling the right story.

Before Robinson came aboard, most of Island’s decisions were made instinctually, but he was a fan of information. Hiring outside companies to conduct market research was expensive, but Robinson thought it was worth it. The first round of qualitative data found that when describing Marley, many of the British respondents used the word “legend,” so picking the album’s title was easy. Though when Robinson dug into the sales figures, he discovered a discrepancy. Marley’s most popular album, Exodus, had sold only about 189,000 copies in the U.K. and under a million copies worldwide. (“That’s small beer,” Robinson quips.) The posthumous Marley album that Island released, Confrontation, didn’t have impressive sales figures either, despite the attention his death received. “What seemed like a big reggae star to me suddenly was obviously a cult figure,” Robinson says. “He hadn’t really crossed over.”

Another round of research found that without really knowing his music, older listeners thought that Marley’s lyrics were anti-white, which turned them off. Looking to showcase the half of the story that hadn’t been told, Robinson spent months driving the M4 motorway near Island’s office with his pregnant wife, tinkering with the track list. Though the final version does include the songs “Get Up, Stand Up” and “Exodus,” Legend downplays Marley’s stance as a freedom fighter and instead emphasizes his romantic side, where he’s either pining for or comforting the ones he loves.

Robinson also said that Island had often used images of Marley dressed in militaristic clothing or looking confrontational. For the collection’s cover, he found a picture by photographer Adrian Boot where Marley appears contemplative and more approachable. “The research had pointed us in the direction of a songwriter—a guy with a philosophy, a visionary kind of thing,” Robinson says. It’s also important to note that during the mid-1980s, dreadlocks were far less prevalent or socially acceptable among the British public, so Robinson picked a photo that downplayed Marley’s hair instead of calling attention to it, as Blackwell had initially wanted.

Once Legend was out, Robinson pushed to advertise it heavily on British television. It was a high-priced tactic, but in a country with only a few channels and no cable at the time, it provided a captive audience. Though selling vinyl was still the top priority for labels at the time, he also invested in high-quality cassette tapes, knowing that people couldn’t take their record players with them when they went on their upcoming summer vacations. “I’m told that that year, the tourist beaches of Europe hummed with the sound of Bob Marley,” Robinson says.

As Blackwell writes of Legend in his memoir, The Islander, “It wasn’t put together with love, but it was put together with a great deal of care.” In 1984, it reached the top of the British albums chart and the no. 54 spot on the Billboard 200, and it’s mostly stayed around ever since. It finally broke Billboard’s top 10 in the U.S. in September of 2014 when the Google Play store slashed the price to 99 cents. After Billboard established the Vinyl Albums chart in 2011, Legend entered it for the first time the following year and has now spent 327 nonconsecutive weeks there—the fourth most for any album overall and the most among greatest hits collections.

Robinson didn’t stay at Island for long, despite the success of Legend and the band Frankie Goes to Hollywood; he soon left to focus again on his new Stiff Records signees the Pogues. He mentions that, because he was a contracted employee, he’s never collected any royalties from Legend’s millions of sales. In 1986, Island released Rebel Music, a 10-song collection consisting entirely of Marley’s political songs that Blackwell put together as a rejoinder to Legend. The highest it’s ever gotten on the U.K. charts is no. 54, while in the U.S. it peaked at no. 140. It remains largely forgotten.

In late January 2023, the Bob Marley One Love Experience arrived for a five-month stint in Los Angeles. The Instagram-friendly pop-up installation featured exclusive photography, memorabilia, and art that pay homage to Marley. For the official guide of the VIP tours, they tapped Roger Steffens, the longtime reggae advocate and archivist who turned decades of his interviews into the book So Much Things to Say: The Oral History of Bob Marley. (Some may also know his past exploits from the Family Acid account on IG that his daughter, Kate, runs.) During every tour, he’d ask people what their favorite Marley song is. Many of them answered “Three Little Birds,” best known for its breezy “don’t worry about a thing” refrain. “It’s a lightweight song, but those are the kinds of songs people think of mostly,” Steffens acknowledges.

When asked about the effect of these types of tracks’ dominance on Legend, he says, “They neutered his revolutionary image.”

After the release of Legend, Marley’s music became most broadly associated with a state of mind where it’s perpetually summertime and the skanking is easy. The police on The Simpsons vibe out to “Jamming” when they blaze a blind man’s weed, and the Jamaica Tourist Board used reworked versions of “One Love” in commercials for decades. Even if these songs are not political in content, that doesn’t make them any less incredible. They’re perfect pop compositions that you can hear one time and feel like you’ve known forever.

When Bob Marley and the Wailers joined Island in the early 1970s, the label’s intention was always to market them to a white audience. The group had success in their native country as a ska and early reggae act, but they hadn’t been able to cultivate an international audience. Blackwell sold Marley on the concept of treating them like a rock band. “Even Bob didn’t initially understand my line of thinking until I took him to a show in America, an Island tour with Traffic, Free, and John Martyn,” he writes in The Islander. “It was sold out, even though none of these artists had actual hits. They represented the new album market: white college kids into Led Zeppelin and Cream who thought pop was too superficial and throwaway.”

Of course there are multiple kinds of white college students, who then grow up into different kinds of white adults. Sure, there are politically active ones who are curious about the cultures and realities of other countries. Then there are plenty of ones who just want to party and whose interest in reggae is worthy of a withering punch line in Ghost World. There are even ones who take up Rastafari cosplay and want to chant down Babylon from their dorm rooms—the kind that the Lonely Island parodied in their song “Ras Trent.” For all of them, Legend is often the common entry point.

Asked what it is about Marley that resonated (and continues to resonate) with college students, Steffens replies, “It’s herb, which is not quite as rebellious as it was once now that you have dispensaries on every other corner. But still, it has a little veneer of unacceptability about it. Also the fact that he was a rebel. No way around that fact. He was encouraging people to fight against every law and every government on this planet that is not legal. He said the only law that is legal is Jah’s law.”

That rebellious influence still found ways to push through even as the good-times associations with Marley rolled on. In 1992, Sinéad O’Connor sang an a cappella cover of Marley’s “War” on Saturday Night Live before ripping up a picture of Pope John Paul II. When she was greeted with boos at Madison Square Garden two weeks later during a Bob Dylan tribute concert, she stopped the backing band from playing the other canonical Bob’s “I Believe in You” and defiantly performed “War” again.

It’s not as if the non-righteous Bob Marley songs that became inescapable were conjured from nowhere or were unearthed from some hidden vault after his death. He recorded them, put them on albums, and regularly performed them. Bob Marley: One Love depicts the attempt on his life in Jamaica in December 1976 and the time he spent afterward in London recording Exodus before returning home to play the monumental One Love Peace Concert in April 1978. Side A of Exodus is indeed political, while side B features four of those seemingly innocuous songs featured on Legend. And it’s not Marley’s fault that there’s something about “Redemption Song,” a lamentation about the intergenerational mental trauma caused by chattel slavery, that makes people want to play it on an acoustic guitar when they’re sitting around a campfire.

“What [Legend] has done to forward Bob’s music to a demographic that wouldn’t necessarily listen to reggae or wouldn’t listen to Uprising or Confrontation or Catch a Fire or Burnin’ or any of those albums is huge,” says Dan Sheehan, the co-owner and producer of the California Roots Music and Arts Festival in Monterey.

Cali Roots is one of several festivals that are evolutions of the local Bob Marley Day celebrations that sprouted up after his death. While those events initially focused specifically on reggae artists, these newer fests also book acts from scenes like hip-hop, modern funk, and jam bands. In 2022, Goldenvoice, the promoters behind the Coachella festival and hundreds of other concerts a year, held the first edition of Cali Vibes, an annual three-day event in Long Beach. That Saturday night featured a joint headline performance by Ziggy, Damian, Stephen, Ky-Mani, and Julian Marley, in which they did covers of their father’s songs. “We were going through a time where it was very critical that you not forget where this came from,” says Nic Adler, the vice president of festivals at Goldenvoice and the producer of Cali Vibes. “Putting Bob’s family at the top of the bill, collectively, there was no question. It helped us define what that show was.” The other headliners that weekend included Dirty Heads, Rebelution, and Sublime With Rome. (Three bands that can be loosely described as “reggae rock” and are more likely to be found at the KROQ Weenie Roast than Sumfest.)

Nic’s father, Lou, is a legendary figure in the entertainment industry and was one of the original creators of the Roxy in West Hollywood—a club that Nic took over in 1999. Bob Marley and the Wailers’ performance at the Roxy in 1976 was a famous bootleg for decades before it saw official release in 2003. But Nic didn’t start listening to Marley’s music until he was a teenager in the ’80s, after getting turned on to it by his younger brother Cisco, who spent his childhood in Hawaii. “Probably the second song you hear when you’re a little kid in Hawaii is ‘Three Little Birds,’” Adler says.

He thinks that Legend, alongside Exodus, is the Marley album he’s listened to the most in his lifetime, but he admits he’s heard it only a handful of times over the past 25 years. “Legend is a gateway to something much deeper and meaningful, but you have to get people there,” he says. “That’s not just for Bob, that’s for whole genres of music. That goes from dancehall and dub all the way into American reggae, and probably this transition we’re seeing into Afrobeats. I don’t know if I would be interested in knowing who the next artist from Ghana is [without Legend], and to me, that stems back to what was a commercialized version of Bob.”

Over time, Marley’s fame has grown across the world, far beyond just white fans in North America and Western Europe, or fans in his native Jamaica, where he remains a towering figure who’s lionized alongside former Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie and the Pan-African activist Marcus Garvey. “You can go to China and you don’t hear Bruce Springsteen, but you hear Bob Marley,” says Chris Salewicz, the author of a 1979 profile of Marley in NME and the book Bob Marley: The Untold Story. “I was in Senegal, in West Africa, in some tiny little bush hamlet, and there’d be a giant mural of Bob Marley.”

Despite his efforts during his lifetime, Marley was unable to gain a major following among Black Americans. Bruce Talamon photographed him multiple times for SOUL Newspaper when he came through Los Angeles, giving exposure that Marley appreciated. (Particularly since, Talamon says, Jet and Ebony publisher John Johnson refused to put him in his publications because he did not look “respectable” and openly smoked marijuana.) “Black people are not monolithic, of course, but I think sometimes people forget that Black folks are a little bit more conservative than white people might think, especially during those years,” Talamon says. “When Bob was presented, there was a segment of the Black population that wasn’t going to have anything to do with it.”

Over time and in subsequent generations, Marley and his music have been championed by the Black community. Steffens notes that over half of the people he took on tours of the Bob Marley One Love Experience were African American. “In a sense, it’s like the classic civil rights issues,” Talamon says. “Now everybody loves Malcolm, but back then there were a lot of people who did not embrace Malcolm X as they embraced Martin Luther King Jr.”

Talamon traveled with Marley for his concert in the African coastal country of Gabon. It was part of a short string of performances in the continent at the start of 1980, where he found an enthusiastic response. “He wanted to reach back to his African roots,” Talamon says. “We can only speculate, if he had lived, what else he would’ve done.

“I mean, he was revered by people who were in South Africa,” he continues, “so he spoke to people who had the boot on their neck. What he did was revolutionary.”

As culture shifts, Marley’s imprint has found ways to adapt within it. The Jamaican novelist Marlon James’s book A Brief History of Seven Killings from 2014 is a mystical and multilayered exploration of how the attempted assassination of the singer reverberates across lives and time. EPMD sampled Eric Clapton’s cover of “I Shot the Sheriff” for their single “Strictly Business,” while Naughty by Nature sampled Boney M.’s cover of “No Woman No Cry” for their hit “Everything’s Gonna Be Alright.” Though “Everything’s Gonna Be Alright” uses Marley’s reassuring words for its chorus, its original title upon release was “Ghetto Bastard,” and the verses are bleak, more reflective of the harsh realities described in Marley’s political songs. “‘O.P.P’ was a party record,” says KayGee, the group’s DJ and producer. “‘Everything’s Gonna Be Alright’ was the record that hit home and told our story—coming from New Jersey, coming from East Orange, coming from the struggle. We thought that it represented us.”

De La Soul was the first group to really explore the recontextual possibilities of Marley’s music in hop-hop, incorporating the syncopated guitar part from “Could You Be Loved” into the disco-rap throw-down “Keepin’ the Faith.” Maseo, the group’s DJ, was the beat’s chief architect and was inspired to blend Marley with the bass line from Slave’s “Just a Touch of Love” by his genre-spanning sets at parties. Maseo spent his first years in Brooklyn, raised by a single mother who often had Jamaican boyfriends. It was she who first bought Exodus and who played Marley albums around the house on weekends. “Between reggae and calypso, that’s embedded in my DNA,” he says. “[Marley’s] music was tremendously impactful.”

For the score of Bob Marley: One Love, director Reinaldo Marcus Green tapped 34-year-old composer Kris Bowers—a veteran of his other projects, as well as multiple films and TV shows for Ava DuVernay and Shondaland productions. Along with inserting thematic elements from specific Marley songs into the score, he also recorded Nyabinghi percussionists—traditional Jamaican music that was always important to Marley.

Bowers grew up ambiently aware of Marley’s songs, but he only seriously explored his music after a classmate at the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts performed “Redemption Song” at a concert. “Before I did my first dive into him, I always thought of reggae music as music that you listened to when you’re high, and it’s all about being chill and laid-back,” Bowers says. “I had no idea how strong of a presence [Marley] had and how much conviction he had as a human being. What he was saying has nothing to do, for the most part, with sitting back, and definitely not any sort of complacency. It was about trying to reach and push and strive for something and reaching for humanity.”

But how do you keep people interested in music that’s over 40 years old in these constantly shifting, content-heavy times? As a music and film producer, Lou Adler was part of key pop culture moments, including The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Carole King’s Tapestry, and Cheech and Chong’s Up in Smoke. His son Nic has witnessed how important it is to continuously repackage and remind people of this history in order to keep it in the public consciousness. “There are these new mediums that come up,” he says. “Each time, there’s that discovery or rediscovery for people. That’s always important with something so culturally relevant as Bob’s music. There’s not a time when there’s not the right time to discover his music. But is it on the right platform? Is it available? Is it accessible? If it continues to be, it should never go away.”

Early reviews of Bob Marley: One Love have not been kind, but with a sparse lineup of new releases arriving in theaters, it’s still predicted to arrive near the top of the box office after its first weekend. It joins a list of estate-endorsed Marley endeavors, including a documentary, deluxe anniversary editions of his albums, weed strains, coffee, remix collections, reconfigured compilations and soundtracks, and much more. None of them have had anywhere close to the longevity or the sales of Legend. Then again, not really much else in the world has. “The public liked the record as it is, and it hasn’t particularly incented them to buy some other,” Legend’s architect, Robinson, says. “It was great as it was, and we got it right and did it well.”

Eric Ducker is a writer and editor in Los Angeles.