In the finale of True Detective: Night Country, Beatrice, a former cleaning woman at the Tsalal Arctic Research Station, makes a quasi-confession to detectives Liz Danvers and Evangeline Navarro. “It’s always the same story with the same ending,” she says. “Nothin’ ever happens. So we told ourselves a different story, with a different ending.”

Night Country told a different story, with a different ending, than the three True Detective seasons that preceded it. This story lasted six episodes instead of eight. And its ending was, well, divisive, yielding some effusive praise but plentiful pans. No one can complain, like Bee, about nothing happening; if anything, too much happened, as Danvers and Navarro found the suspect they’d been searching for all season, (sort of) solved eight murders, shut down the mine that was polluting Ennis, and (probably?) survived multiple life-threatening predicaments. All of that and more had to happen in one supersized season-ender because there were so many mysteries still unsolved and no more episodes left in which to tell the tale. A day after it aired, the finale sported the season’s lowest average IMDb user rating.

Night Country has company, in more ways than one. The six-episode season, which was once almost unheard of in Hollywood, has become increasingly common. And the format’s track record is checkered enough that there is some cause to be concerned when a series gets a six-episode order. I’m not saying there’s no place for six-episode seasons in the modern American TV landscape. I’m just gently suggesting that maybe the trend has been taken too far.

According to showrunner/writer/director Issa López, the decision to limit Night Country to six episodes was entirely hers. As she explained to Polygon:

In my initial conversation with HBO about it, they were like, “How do you feel about True Detective?” and I told them what I had in mind. And they said, “We love it. 10 episodes?” And I was like, “No,” because I wanted to direct every one of them, you know? And as time went by there were several conversations where they were like, “Seven?” and I was like “No, six.” It was always six. It is tight for all the terrain we cover in the series, but at the same time, I am a firm believer in economy and saying what’s necessary and never overstaying your welcome, leaving people wanting more. So it was a perfect size, I think.

A good deal of the audience seems to disagree, judging by the widespread consternation about the season’s length and the common critiques of the show’s pacing. Night Country felt, at times, like a movie stretched to six episodes, or an eight- or 10-episode season compressed into six. Some of the subplots—Hank Prior’s fake fiancée, Pete Prior’s family life, Julia Navarro’s mental illness—begged to be either curtailed or developed further, leading to dueling impressions that the show was somehow both padded and rushed. And as for those unsolved mysteries: Most of the central tensions of the season were resolved, and some were intentionally left ambiguous, but some reveals seemed abrupt, and some loose ends lingered. “Some questions just don’t have answers,” Danvers says in the finale, but maybe more questions could have been addressed satisfactorily—and more characters could’ve been given greater depth—with an extra episode or two.

In a 2015 Vulture story titled “How Long Should a TV Season Be?,” TV critic Margaret Lyons wrote, “Six episodes is the wrong length. It’s too short. That is not enough TV to constitute a ‘season.’ … Six episodes is an acceptable length only for a miniseries, and even then, maybe we’d be better off with either more or less story.” In the nearly nine years since, TV makers have roundly rejected that stance.

There was a time, not terribly long ago, when the six-episode season was a distinctly British institution, as foreign to Americans as the metric system, driving on the left side of the road, and calling TV “telly.” As someone who grew up watching (and wondering why there wasn’t more of) the classic BBC sitcom Fawlty Towers, I cherished a Simpsons line (from the 15th episode of the series’ 22-episode 11th season) about a fictional British sitcom called Do Shut Up: “Not hard to see why it’s England’s longest-running series—and today, we’re showing all seven episodes.” Sixteen years later, when The Good Place made essentially the same joke—“It ran for 16 years on the BBC. They did nearly 30 episodes.”—the average length of a U.S. TV season was already declining, but the six-episode season was still a real rarity.

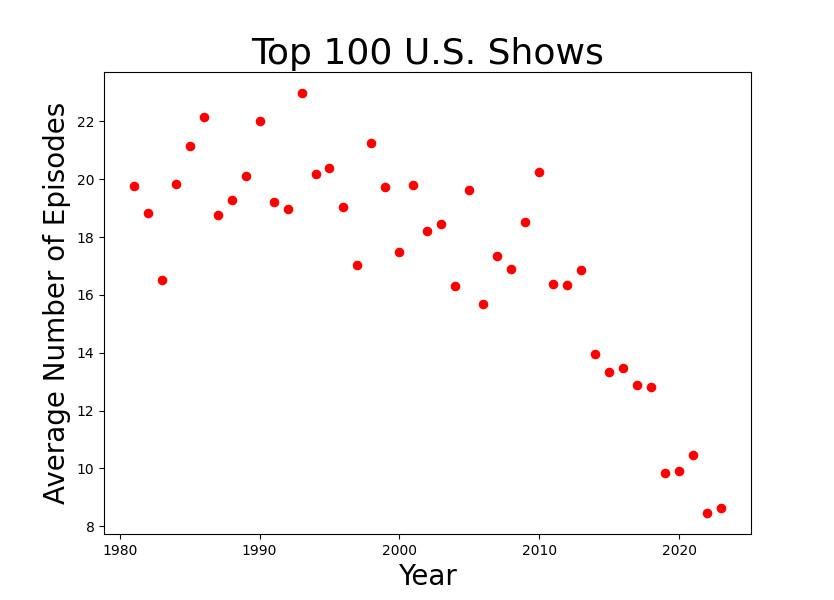

It’s not news to anyone that TV seasons have shrunk, but the degree and rate of the change are still shocking. The chart below shows the average number of episodes of the top 100 U.S. scripted series (by average IMDb user score) in each year dating back to 1981, excluding extremely prolific soap operas.

In the ’80s and ’90s, the average length of highly rated TV seasons typically approached or exceeded 20 episodes. Although the decrease set in around Y2K, a 20-episode average appeared as late as 2010. The drop-off post-2010 has been precipitous: In the past two years, the averages have barely been above eight, roughly half of what they were a decade ago. We can trace this progression through the lens of Star Trek: Although there are more Star Trek series than there have ever been before, most of today’s Trek shows feature 10-episode seasons, compared to the previously standard 22 to 26.

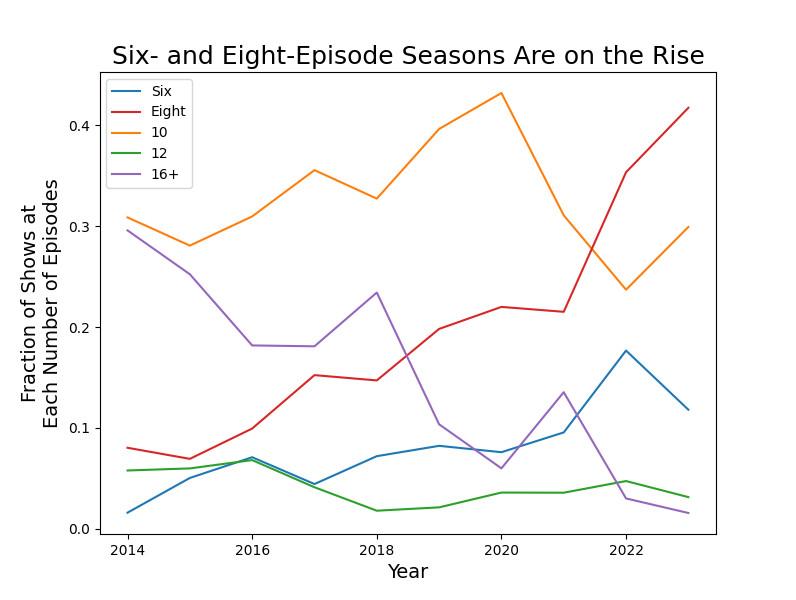

In light of that plummeting average, it’s no surprise that over the past 10 years, six- and eight-episode seasons have made up a growing percentage of all scripted series, while higher-episode-increment seasons have accounted for smaller and smaller portions.

Unlike the fate of Night Country’s Oliver Tagaq, the causes of this redistribution of season lengths aren’t a mystery. The pursuit of prestige has led to an emphasis on quality over quantity—which manifests in less filler and higher (read: more expensive) production values—and a preference for and deference to auteurs like López, who may want to write and/or direct every episode personally. (Two of the reasons—along with a lack of syndication incentives, less clement weather, and a smaller population and, thus, a smaller scale—for British TV’s habitual brevity.) Shorter seasons also reduce the risks networks incur on any individual series and allow actors to work on more projects. Of course, the incredible shrinking season has been driven or exacerbated by the ascendance of streaming networks, which may prefer binge-friendly lengths and don’t care about syndicating series or filling broadcast time slots. (Netflix’s first original series, Lilyhammer, premiered in 2012 with a binge-dropped eight-episode season.)

As I wrote in 2017, one downside of this lower-volume, pick-your-spots-style approach is that we’ve lost potential time with the sort of special shows that maintained a consistent quality level over longer seasons. On Star Trek: The Next Generation, The Good Wife, and Frasier, respectively, Jean-Luc Picard, Diane Lockhart, and Frasier Crane used to keep us company for half the year. On Picard, The Good Fight, and Frasier (the new one), they were much less frequent guests on our screens. And it’s not just that the more recent seasons run for 10 episodes instead of 22-plus; it’s also that the breaks between are longer. As Alan Sepinwall wrote last week, “So much time passes in between seasons that it’s hard to both remember and feel emotionally connected to everything after a long hiatus.”

In the case of a compelling 10-episode season that theoretically could’ve been a strong 20-episode season in an earlier era, the result is less of a good thing. When 10 episodes dwindle to six, though, the cost could be even steeper: not just less of a good thing, but a less good thing. At a certain point, that is, whittling away episodes doesn’t leave a leaner, harder-hitting season behind; it weakens the load-bearing structures that support the season’s arc. And that point, some evidence suggests, is six episodes.

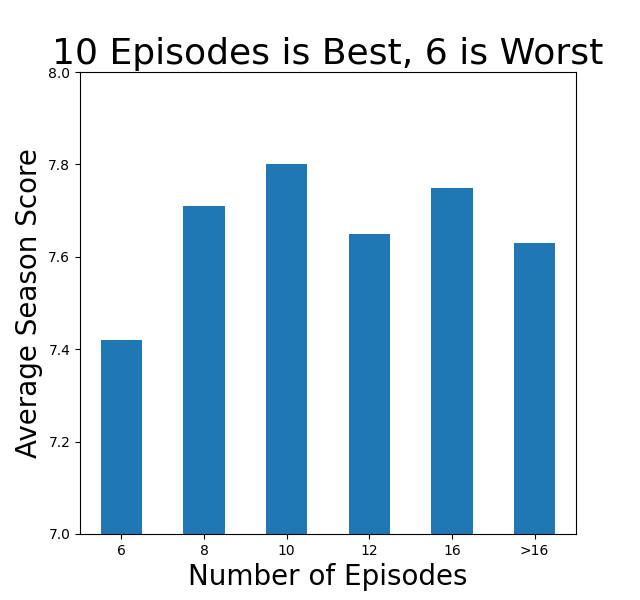

Why should we side-eye the six-episode season? Check out the chart below, which shows the average IMDb user rating for scripted seasons since 2014, broken down by number of episodes.

Ten episodes—for what it’s worth, the order López said HBO had in mind for Night Country—seem like the sweet spot, but most other lengths fall in roughly the same range. Except for the six-episode season, which is clearly a cut below.

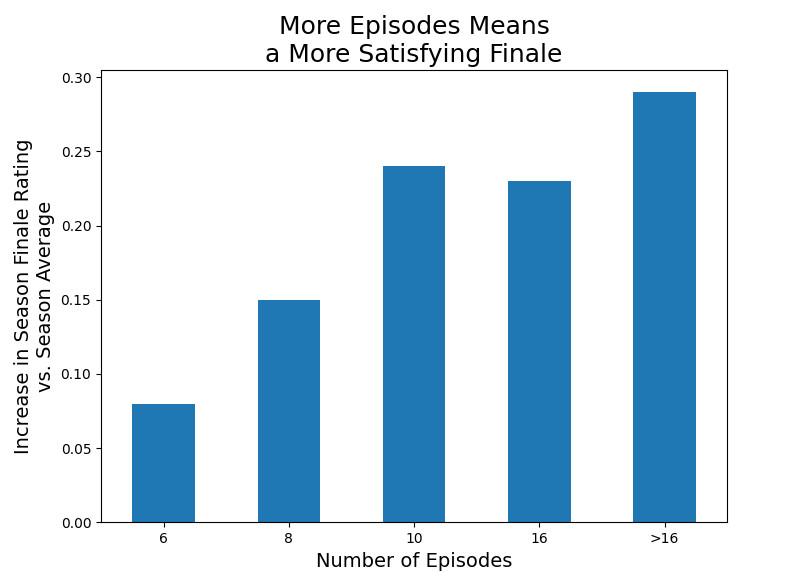

Six-episode seasons also rate poorly in a second, related respect: They’re prone to weaker finales. On the whole, finales tend to post above-average scores. And in general, the longer the season, the higher the score for the finale. The finales of six-episode seasons are barely better than the average episode.

One might suspect that longer seasons contain more exposition, setup, and detours that drag down their averages, thereby making it easier for the finales to stand out. Given that the six-episode seasons receive the lowest average scores, though, they clearly aren’t all killer, no filler. Maybe their finales flop, relatively speaking, because six episodes aren’t enough to generate sufficient suspense or because there’s not enough screen time to tie up and pay off plot threads.

If we want to slice and dice the data more thinly—granted, we’re getting into “analyzing the crosstabs in political polls” territory here—we see some signs that certain genres are especially dicey six-episode propositions. Six-episode seasons classified as mysteries, crime shows, and dramas all have flimsier finales (relative to their baseline season scores) than even the average six-episode season, possibly because the more complex and serious the stakes, the harder they are to build up and bring to fruition in six episodes (True Detective is classified as a drama, a mystery, and a crime show, so historically speaking, the deck was stacked against Night Country, especially considering the added narrative burden of its ties to Season 1).

Admittedly, we’re dealing with, at most, modest differences; it’s not as if six-episode seasons are doomed to be bad or anticlimactic. Over the thousands of seasons that constitute this combined pool, though—10 years of “too much TV”—those differences are meaningful. And six is the unluckiest length. Maybe it’s too little TV.

Now, a couple of caveats. We’re really looking at correlation, not causation: We can’t say with certainty that six-episode seasons (and their finales) have scored worse because they were only six episodes. It could be that shows with weaker bones or skimpier source materials are more likely to get shunted toward six-episode seasons, while higher-ceiling series are steered toward eight or 10; in other words, maybe a 10-episode order is a vote of confidence in a series’ inherent appeal. It’s also possible that six-episode seasons are more likely to come early or late in a series’ life span, when it’s still finding its footing or running out of runway, à la the first seasons of Parks and Recreation and Fear the Walking Dead or the last seasons of The Expanse and Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan. Not many series significantly change their episode counts from season to season, so we don’t have a huge dataset of season-switchers to study, and we can’t exactly A/B test TV season length to see which length produces the ideal outcome, all else being equal. We’ll never know whether the seven- or 10-episode versions of Night Country would’ve been better than the one we got. (It’s quite possible that they would’ve been worse!)

It’s nice that actors today get to play more parts and that not every series needs to be built to last. TV seasons aren’t one-size-fits-all: Different series are suited to different lengths, and it would be silly to stretch six episodes’ worth of story onto an eight- or 10-episode frame. Historically speaking, though, six-episode seasons have tended to be lower-rated than longer seasons, with more deflating finales. With that track record in mind, you’d be justified in looking slightly askance at the prospect of a six-episode season, relative to more extended alternatives.

Again, though, season length hardly determines quality. Marvel’s small-screen MCU efforts started strong on Disney+ with the nine-episode WandaVision, but subsequent six-episode efforts—most notably Secret Invasion but also, to some extent, The Falcon and the Winter Soldier, Ms. Marvel, Moon Knight, and Hawkeye—have had forgettable runs or lackluster finales. However, Marvel’s two six-episode seasons of Loki are two of the highest-scoring on record. The Walking Dead’s six-episode spinoffs have seen similarly variable results: Tales of the Walking Dead was a snoozer that hasn’t earned a second season, while Dead City was so-so and Daryl Dixon was a qualified win. HBO disappointed with The Undoing, The Third Day, and arguably Night Country—though Night Country got good reviews initially and drew a robust audience—but achieved its typical quality with Show Me a Hero, We Own This City, The Time Traveler’s Wife, and The White Lotus Season 1 (Season 2 expanded to seven episodes).

In lieu of listing many more examples of the positive (Black Bird, Dark Winds, Schmigadoon!, Corporate Season 3) and negative (Citadel, Sex/Life Season 2, Soulmates, Moonhaven) sides of the six-episode ledger, I’ll leave you with one intriguing—and encouraging—takeaway. Some of the highest-scoring six-episode series in our sample—The Night Manager, Slow Horses, Good Omens, The English, Belgravia—were made by Brits or were British-American coproductions. Maybe American creators are still getting the hang of a form that U.K. creators have learned to deal with over decades.

One would hope the Yanks will catch on: We may be in for more six-episode seasons, seeing as the industry is in the thick of what former network executive and current Substack author the “Entertainment Strategy Guy” identifies as “a general pullback in TV production, as the streamers focus on profitability” and “a decline in big budget and expensive shows in general.” Thanks in part to streamers’ belt-tightening and in part to the strikes, 2023 was the first time since at least 2012—save for the 2020 pandemic year—that the number of scripted original series dropped. However, the pendulum may be swinging back toward more expansive seasons. Long-running procedurals and sitcoms acquired by Netflix and the like are such streaming juggernauts—shout-outs to Suits and Young Sheldon—that there’s interest in making more like them. The future of TV might look like its past: fewer shows, but larger libraries. Good or bad, six-episode seasons only last so long.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ve gotta go check out the next big Sunday night drama: The Walking Dead: The Ones Who Live. How many episodes is it, again? Oh.

You know what? On second thought, let’s give Shogun a shot.