Before Atlanta Hawks forward Jalen Johnson was an NBA Most Improved Player candidate, before he blossomed into a top-75 player and an untouchable trade target, he “didn’t really see the vision” in his team’s development plan for him.

The no. 20 pick in the 2021 draft, Johnson debuted in garbage time on opening night of the 2021-22 season, but he didn’t exceed five minutes in any game for two months. And why would he have? Atlanta was coming off a conference finals appearance; Johnson was just 19 years old with half a college season under his belt; and the Hawks were already well stocked at the forward positions, with John Collins, De’Andre Hunter, Danilo Gallinari, and Cam Reddish all ahead of the rookie on the depth chart.

So even though the Hawks were excited about Johnson’s potential, they sent him 10 miles down the road—to the home of the College Park Skyhawks, their G League affiliate, to get him more playing time. Years later, Johnson recalls his initial confusion about the move. “When you’re 19 coming in, you’re not used to that type of thing,” he says. “You don’t really see the big picture. You just get drafted, all your friends are, you know, ‘NBA! NBA!’ so you’re not really thinking about the G League.”

The interest and awareness of the teams [now versus then] is very different. When I was in Reno, we practiced out of a public fitness center, where many of our teams now have private facilities that they train out of. It’s night and day.Shareef Abdur-Rahim

But unlike in Atlanta, where he couldn’t crack the Hawks rotation, Johnson thrived on the lower level of the NBA ladder. During his rookie campaign, Johnson played 760 minutes in the G League, versus just 120 in the NBA. He scored 21 points per game for the Skyhawks, with 1.7 steals and 1.3 blocks, and gained the two-way confidence that paved the way for his eventual breakout on the NBA stage.

“I grew up, I matured, and I understood and really took advantage of it as I went along in the season,” Johnson says. “Sometimes you’ve got to wait your turn, you’ve got to be patient. … It’s helped me tremendously, so I’m glad it went that way.”

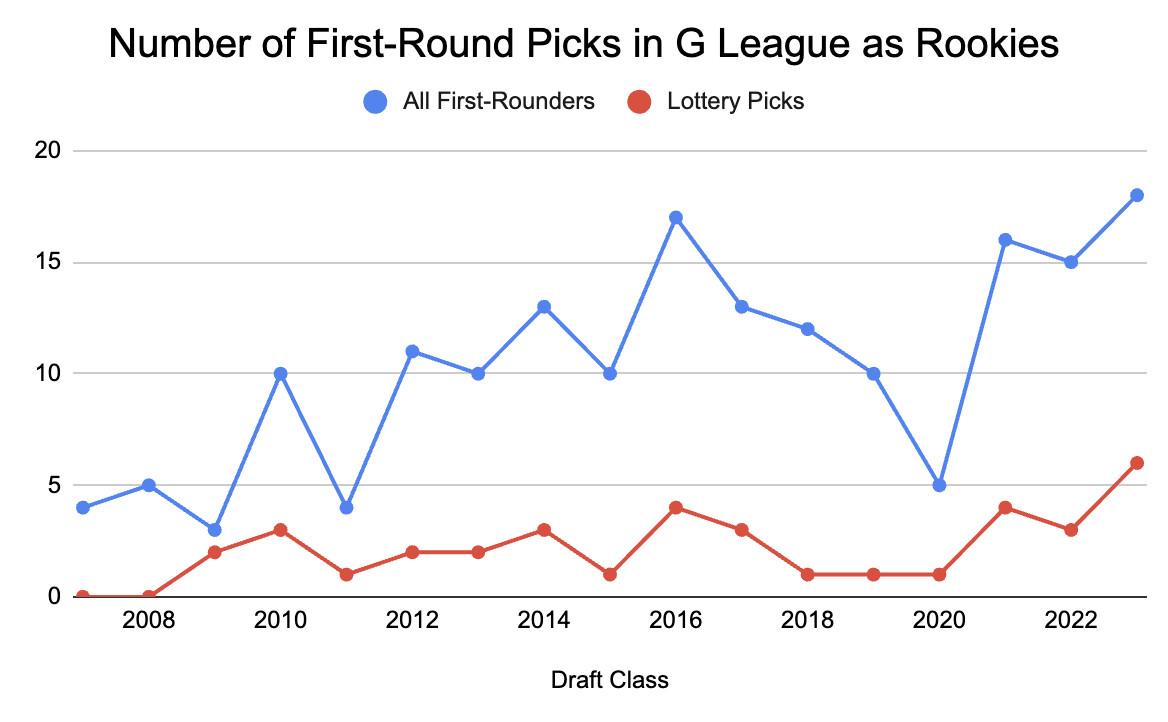

Johnson is far from alone with this sort of story; rather, he’s a member of a growing cohort of promising players who have cut their teeth in the NBA’s developmental league. At least half of the first-round picks in each of the last three drafts have spent time in the G League as rookies.

This season, 18 of last summer’s 30 first-round picks, including six of 14 lottery picks, have played in the G League. Both figures are records for the NBA’s minor league. (The semi-recent dip in this graph is because many G League teams canceled their 2020-21 seasons due to the COVID-19 pandemic.)

The G League–to-NBA pipeline is expanding, not only for undrafted NBA hopefuls but also for touted prospects who need just a little more seasoning. The rewards for a successful transition are profound.

“I’m here because of the G League,” says Derrick White, now a near-All-Star for the Celtics, formerly a first-round pick who helped the 2017-18 Austin Spurs win the G League championship.

Enough players like White have traveled this route that it would now be easy to build an excellent roster composed exclusively of first-round picks with at least five games of G League experience:

- PG: Derrick White

- SG: Dejounte Murray

- SF: Jalen Johnson

- PF: Pascal Siakam

- C: Rudy Gobert

- Backup: Tyus Jones

- Backup: Dennis Schröder

- Backup: Terry Rozier

- Backup: Trey Murphy III

- Backup: Jonathan Kuminga

- Backup: Robert Williams III

- Backup: Clint Capela

“I think it’s changed from being a league full of guys that were overlooked and nobody appreciated to being a league of burgeoning stars,” says Shareef Abdur-Rahim, the former NBA All-Star who now serves as the G League president.

But why now? What was the impetus for more teams to start using the NBA’s little sibling as a staging ground for their first-round picks? And what does that philosophical shift mean for the G League’s future?

The NBA’s current minor league was born in 2001, after the effective collapse of the old Continental Basketball Association, but for well over a decade, it existed mainly on the periphery of the NBA map.

“In theory, the NBA’s own Development League was designed to function as a sort of R&D lab for players too green for showtime. That’s not how it played out,” super-agent Arn Tellem wrote in a 2015 column. Instead, Tellem wrote, “The NBA outsources nearly all of its minor leagues to college basketball and Europe.”

This pattern placed the G League in minor-league limbo. On one end of the player-development spectrum is MLB, in which only two rookies since 2000 have debuted without first playing in the minor leagues. (And one of those players skipped only because baseball’s minor leagues didn’t have a season in 2020.) On the other end is the NFL, which doesn’t even have a minor league and often sees rookies turn into major contributors right away; 48 first-year NFL players started more than half their team’s games in 2023.

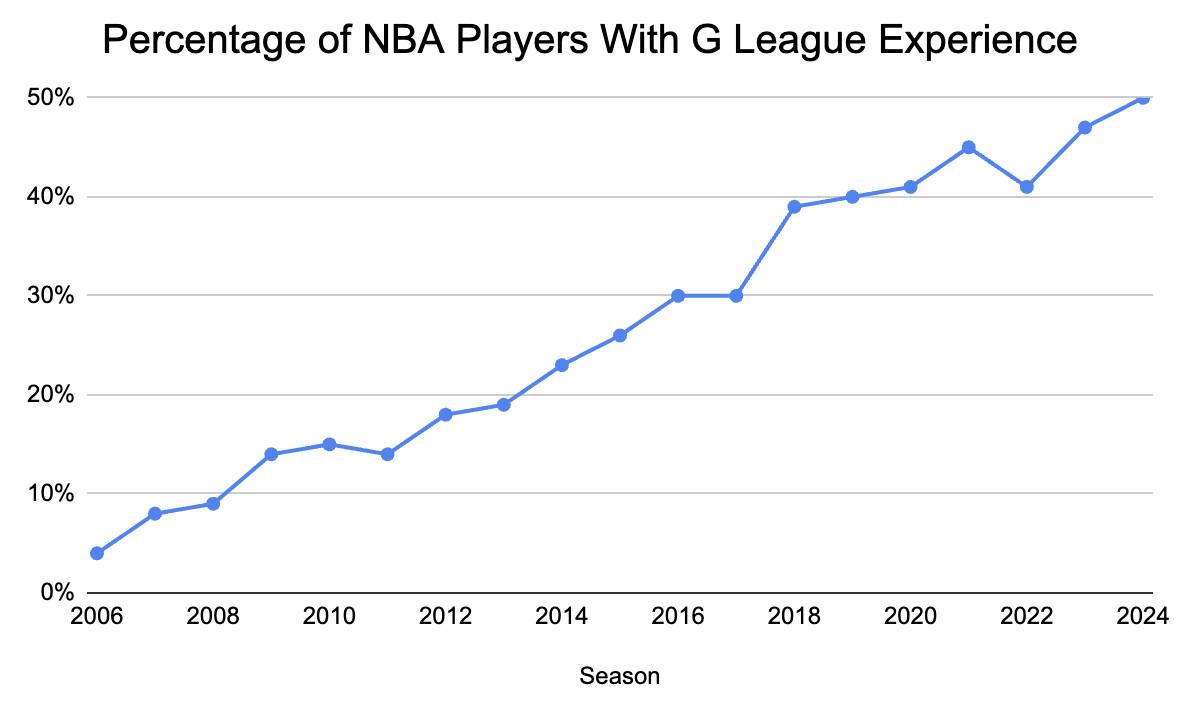

For most of its existence, the NBA hewed closer to the NFL’s model. In 2005-06, according to data provided by the NBA, only 4 percent of players on opening night rosters had any G League experience. And in 2007-08, the first season with G League statistics on NBA.com, not one of the top 20 picks from the previous draft made any G League appearances. (The league was called the D-League, short for Developmental, until 2017, when a partnership with Gatorade precipitated a change. We’ll stick with “G League” throughout this piece for consistency’s sake.)

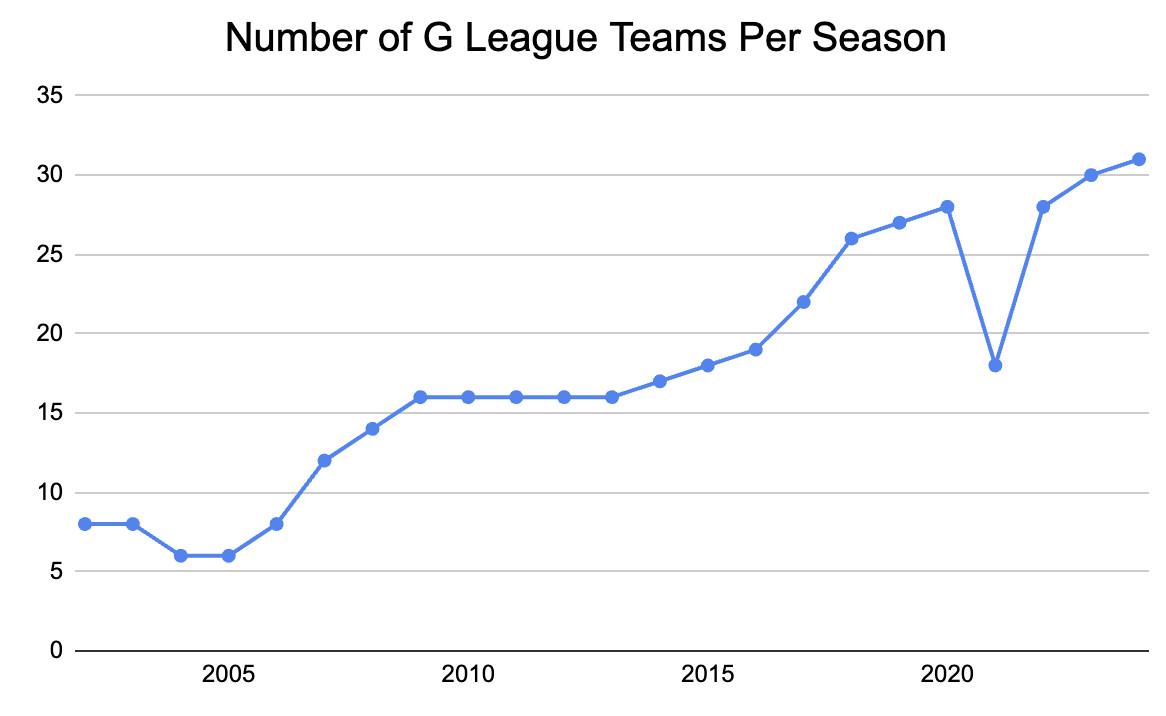

Even midway through the 2010s, the G League was notable less for its players than for its experiments, like the 3-point-heavy approach of the Rio Grande Valley Vipers and numerous rules changes that received an audition at the lower level. The laboratory-like league was smaller, with fewer teams directly owned by NBA franchises. Even those G League squads that were one-to-one affiliates didn’t tend to be well integrated into their parent teams. “People weren’t tracking it very closely,” Pacers coach Rick Carlisle says.

G League rosters were populated mostly by long shots and undrafted players; if a first-rounder was ever demoted, it was typically one who had been picked near the end of the round—and thus joined a loaded NBA roster—or was already trending toward bust territory. Meanwhile, G League coaching staffs were tiny and overworked. Developmental plans were one-size-fits-all rather than specialized for each prospect. Even if they wanted to, it was difficult for front offices to watch games online.

For the players, the NBA’s minor league was a difficult place to develop. “It wasn’t really attractive,” says Windy City Bulls guard Keifer Sykes, who first played in the G League in the 2015-16 season. “The money wasn’t good. The facilities weren’t good. The resources weren’t good.”

Fast-forward to 2024, and the money is better, the facilities are swankier, and the resources are much more elaborate. NBA teams are now investing in the G League as they realize its potential for player development, which savvy clubs like the Heat and Spurs have known for years. By next season, all 30 franchises will own or operate a G League affiliate.

At the same time, the introduction of two-way contracts—now up to three per team—has convinced talent that might have otherwise gone overseas to stay in the U.S., and thus boosted the G League’s level of competition. “On a nightly basis, it could be anywhere from five to 10 actual NBA players, including with the two-ways, on the floor. So the talent level is at an all-time high,” Sykes says.

More concerted effort and attention from parent clubs have led to an improved G League experience across the board. Abdur-Rahim first engaged with the league as the general manager of the Reno Bighorns, who were connected to the Sacramento Kings, in 2013-14. “The interest and awareness of the teams [now versus then] is very different,” the G League president says. “When I was in Reno, we practiced out of a public fitness center, where many of our teams now have private facilities that they train out of. It’s night and day.”

Players say they also benefit from better nutrition, more attention in the weight room, and improved accommodations on road trips. These changes require some financial commitment from NBA clubs, but not a massive one. “It’s not very expensive to run a decent development org down there,” says an executive for an NBA team.

Just as important is building the infrastructure between different levels of the organization. Bigger coaching staffs allow for more individualized attention, and executives say that they function best when they include members with previous experience in the parent NBA organization. This devotion of manpower is also relatively new at the G League level.

“We realized it’s hard to give the players all the attention and everything they need with a limited amount of bodies,” Windy City Bulls coach Henry Domercant says. “If you’re doing the scouting, but you’re still packing the shoe bag and you got to help with the laundry and then drive the bus to drive them home, then you can only help with so much.”

The ultimate outcome of these lower-level changes is a broader strengthening of the G League’s once tenuous connection to the NBA. A record 50 percent of players on opening night rosters this season had previous G League experience.

Where once people weren’t paying much attention to player performance in the G League, Carlisle says that now, “there’s eyes on them every time they step onto a basketball court, whether it’s in our practice facility, whether it’s [in the NBA], or whether it’s in Sioux Falls playing against another G League team.”

Carlisle and assistant coach Lloyd Pierce have printed-out, side-by-side schedules for the Pacers and Indiana Mad Ants that they use to plan out when they can send their first-round rookies, Jarace Walker and Ben Sheppard, down to the G League for more playing time. Then Pierce will review their minutes when they return to the Pacers.

That level of integration of first-round picks like Walker and Sheppard is standard across teams. “The communication for those players is especially significant,” Domercant says. “We are reporting [to the parent team] after every game or after every week, and that goes from the weight room to on-court to practice, how many extra shots they’re getting. We try to be as detailed as possible.”

The result isn’t just a transformation of the G League itself, but an expansion of developmental pathways that scarcely existed before—and that are helping the NBA’s youngest players adjust to life in the pros.

Who better to sing the virtues of the G League than Gregg Popovich, the winningest NBA coach of all time and, coincidentally, one of the first to embrace the minor league as a rehearsal space for first-round picks?

“It’s a lot better to go down there and get 30 minutes than to sit on the bench and be the 12th guy and play every fourth or fifth game for a few minutes,” Popovich says. “So, it’s pretty logical.”

Beyond the broader changes to the G League itself, other contextual factors make it a more attractive option for young players to gain vital on-court experience. For instance, less practice time in the NBA means more need for hands-on instruction. And two-way contracts haven’t just elevated the G League’s talent level, but also removed an excuse to keep young players on the end of NBA benches. A member of a front office notes that before the introduction of two-ways, teams might have kept their young players in the NBA to have enough bodies in case of injuries or blowouts. Now, though, teams can turn to two-way players in those circumstances, freeing their longer-term, higher-ceiling prospects to go to the G League for guaranteed playing time.

And once they’re there, the G League offers a convenient midpoint for players transitioning from college to the NBA—especially those who enter the draft after their freshman or sophomore years. This involves adjustments to both the physicality and speed of the professional game and literal rule changes at the NBA level, like the deeper 3-point line.

“I knew coming in that I was going to do stints in the G League and play a few games here and there, and it was something that I embraced and was looking forward to,” says Peyton Watson, who was picked 30th in 2022 as a freshman out of UCLA and was traded to the Nuggets on draft night. “If you’re a rookie and you’re just getting your feet wet and there’s not a lot of opportunity for you on the bigger squad, then why not go down there, play against pros, and get live reps?”

It’s a lot better to go down there and get 30 minutes than to sit on the bench and be the 12th guy and play every fourth or fifth game for a few minutes. So, it’s pretty logical.Gregg Popovich

Like Jalen Johnson, Watson played much more as a rookie in the G League than in the NBA. Unlike Johnson, Watson watched his NBA team win a title—mostly from the bench. All 14 of the young wing’s playoff minutes last spring came in garbage time; he’d gone from first-round pick to G Leaguer to human victory cigar.

But Watson has blossomed in his second season as a reserve, filling in for departed veteran Bruce Brown. He’s a fierce defender and an improving shooter. And he credits his time in the G League for helping him reach the level where he can contribute, at 21 years old, to a team with championship aspirations.

“A lot of guys look at the G League like a demotion, but that’s not the case,” Watson says. “You’re going down there to work on your game, you’re going down there because your team has a specific development plan for you, and I think that’s really good.”

The specific development plan is key. As Cody Toppert, now the Wizards’ G League coach, told me back in 2020, G League development should be “based on what roles these guys would have to fill at the next level. You don’t necessarily want to be the G League’s leading scorer.”

Teams have communicated that distinction to their players. I’ve talked to a number of rookies who are splitting their time between the NBA and G League this season, and none of them pointed to scoring as their main area of focus at that level. The goal for Gradey Dick, picked no. 13 by the Raptors, is to improve his passing vision. Walker, picked no. 8 by the Pacers, is working on his 3-point shooting. Sheppard, the no. 26 pick for Indiana, was told to improve his defense and “show that I can guard a lot of different positions at a high level.” (One locker over, veteran T.J. McConnell interrupts to joke that Sheppard needs this developmental plan because “you can’t guard your own shadow.”)

Even Cam Whitmore, the G League’s co-leading scorer this season (minimum five games played) and a breakout bucket getter for the Rockets, had to prove his grasp of advanced defensive schemes with the Rio Grande Valley Vipers in order to earn playing time in Houston. Rockets coach Ime Udoka said of Whitmore earlier this season, “He’s not going to have the ball every time with us [on the Rockets], so we send him there to work on specific things, and that’s what we’re monitoring more than the scoring output. … We’re looking at his defense, his rebounding, making the right play.”

If you’re a rookie and you’re just getting your feet wet and there’s not a lot of opportunity for you on the bigger squad, then why not go down there, play against pros, and get live reps?Peyton Watson

G League experience also helps players gain intangible attributes that power them at the next level. “A lot of it was mental,” Watson says of his improvement as a rookie. “Just going down there and getting the minutes, getting the reps, getting the confidence. It meant the world to me because when I came back up to the NBA, I had been playing against pros.”

One crucial mental aspect of a G League assignment is feeling comfortable with what might seem like a demotion. Even with general league trends pointing toward more developmental time, personality still plays a role in a player’s reaction to a G League assignment. “We have our scouts ask any intel source before drafting a player, ‘Would this guy be willing to go to the G League? How would he handle it?’” a team executive says.

Coaches and front office staff agree that a large aspect of a proper G League developmental plan is personality management. “Organizations have learned over time how to create the messaging for the players around ‘This is better for you’ and getting their agent on board,” the executive says.

That process might involve sending assistant GMs to watch a G League game in person, or to otherwise check in on the player to show that they care. Sometimes, the executive adds, “it’s as simple as texting the player after the game, ‘Hey, I watched your minutes from last night, I really liked your decision-making, keep working’ to make them feel like they’re not on an island.”

The sheer number of assignments now also makes this an easier transaction for a young player to stomach. Getting sent to the G League isn’t an individual punishment for poor play; it’s as simple a matter as following the crowd.

“Most of the whole draft class’s first round is in the G League, so it’s nothing new,” Whitmore says, adding that he maintains regular contact with his fellow rookies who “keep coming back and forth.”

“My boy Cam!” Dick lights up when asked about his friendship with other rookies in his position. “When your boys are doing that and you’re kind of doing it together, it’s cool to see. … You feel like you have someone to relate to and you can talk to so many people about it.”

It also helps to look up to role models who have parlayed their G League experience into successful NBA careers. Dick says that he talked to Raptors teammate Pascal Siakam—before the latter’s midseason trade to Indiana—because Siakam was also a first-rounder who spent time in the G League, en route to All-NBA stardom. Dick remembers the advice that Siakam gave the young shooter: “You can’t go in there and try to act like it’s negative, because that’s the worst thing you can do for yourself. [You can’t] go in there and try to act like you’re bigger than you actually are.”

Dick was a lottery pick who a decade earlier would almost certainly have spent his entire season with the Raptors in the NBA rather than playing against the Delaware Blue Coats and Capital City Go-Go. Yet, spurred by the precedent of players like Siakam, Dick—who’s on a scorching hot streak in NBA play over the past month—says that he accepted his G League assignment wholeheartedly. “It’s not anything negative at all,” Dick says. “If I have the chance to get developed at this age, then I’m going to take it.”

Much like the Johnsons and Watsons of the NBA, I also wanted to make the most of my G League assignment; I’d done the research and compiled the statistics, but I also sought to experience the sights and sounds of this level of professional basketball. So earlier this month, I attended two Windy City Bulls games, about 45 minutes west of Chicago.

The casual atmosphere in Windy City’s NOW Arena is reminiscent of lower-level baseball leagues—an unsurprising connection, as Abdur-Rahim says the G League has consciously studied and adopted minor league baseball’s business practices and promotional strategies. On the floor behind one baseline is a dining area with cafeteria-style tables and a buffet. Behind the other is a “Fun Zone” for young fans, age 12 and under, featuring inflatable basketball hoops and a miniature obstacle course, which remains packed throughout both games.

The “Fun Zone” is just one element of an experience heavily geared toward kids. Halftime entertainment is provided by elementary school dance troupes rather than professionals like Red Panda. Other youngsters line up to receive bull-shaped hats from a balloon artist. One fan wears an Henri Drell jersey with a “Looney Tunes” label, from Windy City’s Space Jam theme night in January.

Part of my mission is if one of my players gets an opportunity [for the Chicago Bulls] … they know the plays, they know the sets, they’re comfortable in the system. I think that’ll give them a better chance to stick.Henry Domercant, Windy City Bulls coach

The event’s most symbolic moment comes during pregame introductions. During the announcement of the Windy City starting lineup, the loudspeakers play a version of “Sirius,” the classic Bulls anthem—before pivoting into a mashup with Don Diablo’s up-tempo “Switch.” A G League game is close to an NBA contest, but it’s also its own separate thing.

And yet, despite the vast differences in pageantry and ticket price and jumbotron size, the actual gameplay is not that dissimilar from what I see on a regular basis in the NBA.

The games are definitely sloppier: The G League has a higher turnover rate than the NBA and noticeably less offensive flow from one possession to the next. But just like their NBA counterparts in the modern era, G League teams focus on spacing the floor. They aim to run in transition. They navigate pick-and-roll defense with the same basic principles.

This stylistic similarity is intentional, coaches and players say, to better prepare prospects for the jump to their parent teams. “Maybe we don’t do everything exactly the same, but we’re a ‘dumbed down’ version or a shell version. If they’re going from A to Z, we may go from A to P,” Windy City coach Domercant says about the similarities between his system and Billy Donovan’s in Chicago. “Part of my mission is if one of my players gets an opportunity [for the Chicago Bulls] … they know the plays, they know the sets, they’re comfortable in the system. I think that’ll give them a better chance to stick.”

I ask how Domercant handles a strange dynamic of his role as a G League coach: If Domercant is successful at his job in helping to develop a player, he might never coach him again. Domercant laughs and responds, “I rejoice when they go. I celebrate.”

The Windy City coach adds that sometimes, people tell him it must be tough for a G League roster when its parent club recalls a two-way player or talented rookie who had been developing in the minor league. But a winning record at the G League level is “not the goal. Our goal is to develop the guys that can help the big team.”

(Incidentally, the list of “guys that can help the big team” increasingly includes coaches, in addition to players. Seven of the league’s 30 current head coaches, including a former Coach of the Year, Nick Nurse, and the top two betting favorites for the award this season, Mark Daigneault and Chris Finch, gained experience in the G League coaching incubator before taking control of an NBA bench.)

That subservient relationship will inherently limit the G League’s growth potential. Abdur-Rahim says his hope is for the G League to continue to gain fans and to expand internationally, with teams taking trips to play opponents in Europe and Asia. (The G League is already international in league play since the Mexico City Capitanes joined in 2020.) In an interview this week, he echoed commissioner Adam Silver’s comments that the league would “reassess” the G League Ignite program, which before the introduction of NIL policies in college athletics provided an avenue for pre-draft-eligible players to be paid to play.

But even if the Ignite prove to be short-lived, the league has still managed to open a new developmental path for many young players. The NBA will never—and should never—reach MLB’s level, with a multitiered minor league system that essentially every player traverses en route to the top level. It wouldn’t make sense for a prospect like Victor Wembanyama to play in the G League, even if the no. 1 pick says, “I like to be threatened to be sent to the G League if I don’t play the right way.”

Other than Houston’s Amen Thompson, the no. 4 pick last summer who played two games in the G League this season, only one top-five pick in the NBA.com database played in the minors as a rookie: Hasheem Thabeet, the no. 2 pick in 2009 and a notorious bust. (Thabeet’s demotion came after the Grizzlies tried to off-load him in a trade, even though he was only halfway through his rookie season.)

But with the exception of the very top picks, the development path for first-rounders has changed. The old model has been demoted and doesn’t seem likely to receive a call-up anytime soon. Team executives predict there could be even more G League assignments next season, due to what is widely perceived as a weak draft class.

“If the guy can play, they will play in the NBA,” an executive says, enunciating a long-standing truth of pro basketball. “But just because you know so little about these players and how they’re going to fit, the assumption will always be ‘This guy’s going to have to at least start the season in the G League and then prove it.’”