Alan Rogowski, better known to pro wrestling fans as Ole Anderson, died earlier this week at age 81. The first of wrestling’s original Four Horsemen stable to pass away, Ole was something of a throwback even in that group. While kayfabe cousin Ric Flair, Tully Blanchard, and kayfabe nephew Arn Anderson styled and profiled in tailored suits, Ole cut interviews in screen-printed t-shirts tucked into plain red wrestling trunks. Alongside kayfabe brother Gene Anderson, Ole’s Minnesota Wrecking Crew tag team had run roughshod over the NWA in the 1970s and early 1980s; alongside promoter Jim Barnett, Anderson turned Georgia Championship Wrestling into a worthy opponent to Vince McMahon’s expanding WWF. But a combination of bad luck, bad timing, and bad relationships with his co-workers ensured that Ole, a divisive figure in the sport’s history, would remain a relic of its past, rather than a shaper of its future.

Rogowski’s childhood and young adult life mirrors the backstory of dozens of wrestlers from the 1950s and 1960s. As related in his 2003 autobiography, Inside Out: How Corporate America Destroyed Professional Wrestling, which he co-authored with Scott Teal, Ole grew up the grandson of Polish immigrants and spent his adolescence in St. Paul, Minnesota, working at his dad’s bar and playing various sports.

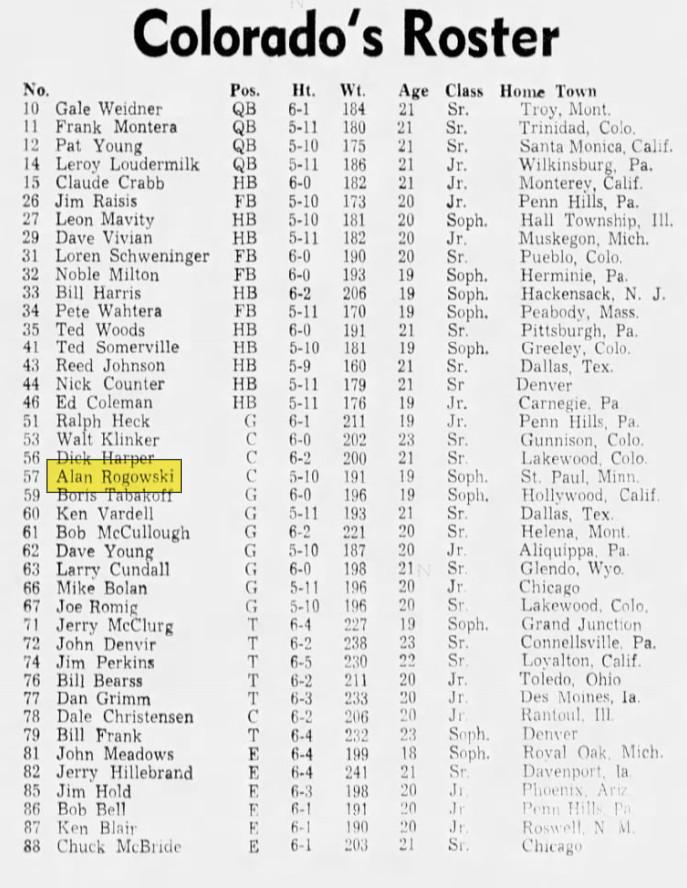

At the urging of Tommy Gibbons, Rogowski began doing isometric exercises and training with hand grippers. In high school, he wrestled at 175 pounds and excelled on the football field—not a superstar, but good enough, at 5-foot-10 and 190 pounds, to make the University of Colorado traveling roster in 1961 (Anderson was always billed at 6-1 in his pro wrestling career, but most reports put him generously at 5-10). He also attended the University of Minnesota and St. Cloud State University, never graduating but keeping his hand in sports, before a three-year hitch in the Army, where he did clerical work and continued training in powerlifting, boxing, and amateur wrestling.

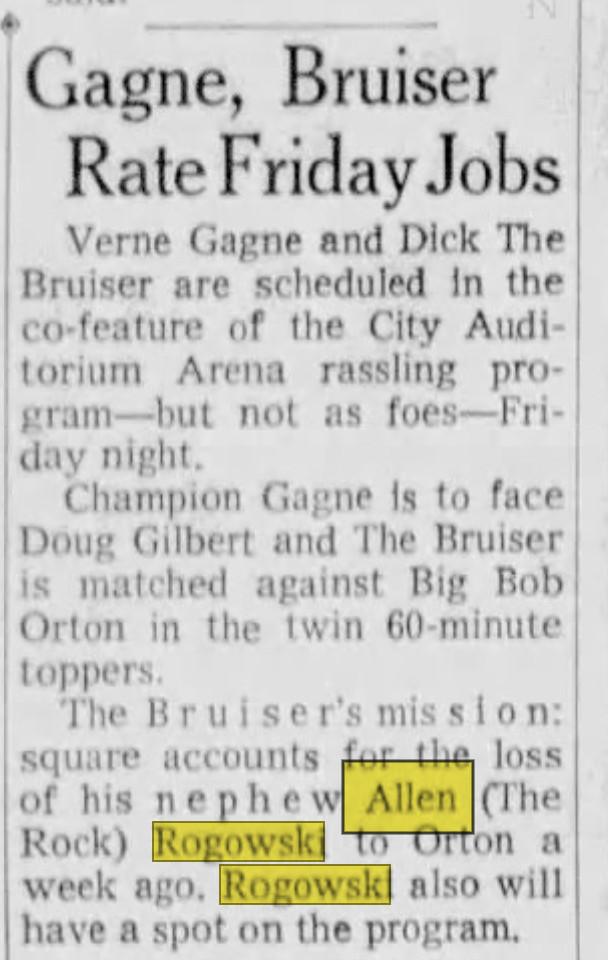

While working out at a YMCA in 1967, Ole—then 265 pounds—was spotted by pro wrestler Tiger Malloy, who introduced him to Verne Gagne, the Minneapolis-based owner of the American Wrestling Association (AWA). Ole admitted he didn’t know much about pro wrestling, but like most Minnesota schoolboys, he was a fan of Gagne, who had been a standout wrestler and football player at the University of Minnesota. After suffering through Gagne’s training, Anderson made his AWA debut as Alan (sometimes “Allen”) “Rock” Rogowski in 1967, enjoying moderate success.

In 1968, he was brought into Jim Crockett’s Mid-Atlantic territory in the Carolinas to join the Minnesota Wrecking Crew, then composed of tough-as-nails Gene Anderson and Lars Anderson, who had a solid amateur background. Rogowski was re-christened Ole, a suitably Scandinavian-sounding name, took the Anderson surname, and enjoyed immediate success as part of a trio of kayfabe brothers. The Carolinas were built around tag team wrestling, and when Lars left for the AWA, OIe became Gene’s full-time tag partner. Aside from a two-year singles run that took Ole back to the AWA and then to Eddie Graham’s Florida territory, Anderson spent the remainder of his full-time wrestling career in the Carolinas and the Georgia territories as a tag team specialist alongside Gene.

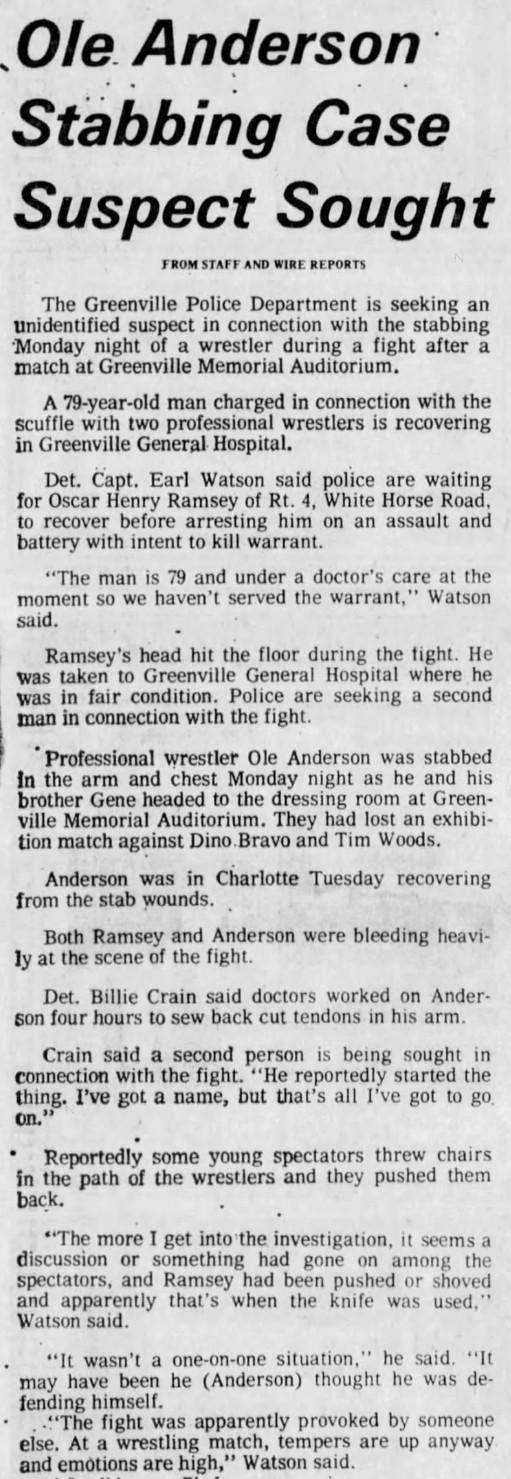

As tag team performers, the Andersons were stiff and believable. They worked the way one might expect a pairing of sibling tag team performers to work, favoring constant double-teaming, tags, and simple offense. As Anderson explained in his book, “[Our opponents] would try to get to the corner to tag their partner, but we would block them” because they wanted them to actually fight like “mad dogs so there’s no doubt in anybody’s mind” that they needed to escape the ring. The crowd certainly bought it: both Andersons were constantly battling with angry crowds. In 1976, while Ole was arguing with a group of fans after a match in Greenville, South Carolina, he was stabbed by a man in his late 70s named Oscar Ramsey.

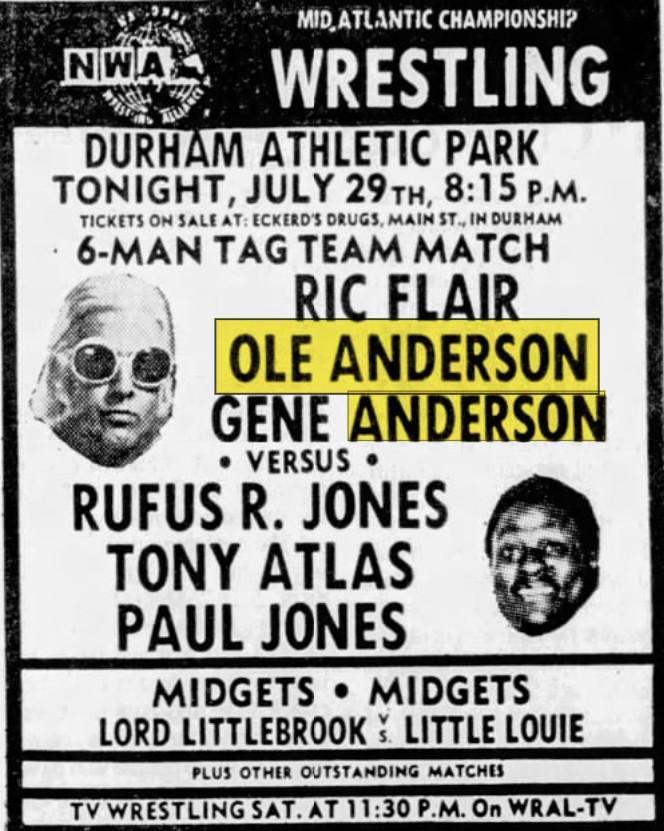

This snug, realistic style, combined with good minds for the business, made the Andersons one of the top-earning acts of the 1970s, particularly among wrestlers who stayed in one or two territories and never held the NWA Worlds Heavyweight Championship. Along the way, they broke in a young Ric Flair, another Minnesota native, as a kayfabe cousin in the 1970s. Then, as Gene’s career wound down in the mid-1980s, they pulled in a stocky, bearded wrestler in his mid-20s known as Arn Anderson, who was either Ole’s brother, cousin, or nephew, depending on who was promoting the match.

The late 1970s and early 1980s represented Ole’s heyday in the business. It was during this time that he became part-owner of Georgia Championship Wrestling, after a series of issues backstage with performers and their pay led Barnett to sell shares of the promotion to Ole, former NWA champion Jack Brisco, and his brother Gerald Brisco. With Ole booking the matches, GCW became a very profitable territory—in part due to national TV syndication on Ted Turner’s Turner Broadcasting Station.

Unfortunately for Ole, who made many enemies in the business with his abrasive, old-school manner, the Briscos and Barnett eventually sold their shares in GCW and time slot on TBS to Vince McMahon, who was rapidly expanding the New York-based WWF as a means of consolidating the territories that made hardasses like Ole relatively wealthy.

It was the first of many embittering moments for Ole, who had enjoyed a charmed career. Now in his 40s and nowhere near his physical peak, Ole found himself as the fourth and eventually fifth wheel (behind manager J.J. Dillon) of the Four Horsemen, a stable that coalesced in 1986 in opposition to perennial Jim Crockett Promotions good guys like Dusty Rhodes, Magnum T.A., and the Road Warriors. Although Ole worked well together with Arn Anderson, using tag team tactics similar to what he and Gene had used, his no-nonsense promo style was out of sync with second-generation star Blanchard and flashy centerpiece Flair. When Ole got booted from the group in favor of Lex Luger, it felt overdue—though he would rejoin a reformed Horsemen in 1989.

From there, Ole played a role in the ups and downs of World Championship Wrestling—born from the accumulated territories that Jim Crockett Jr. sold to Turner—in 1988. He was part of one of that company’s best years for on-screen wrestling, in 1989, while having to appease company mandates to book more cartoonish storylines, similar to what made WWF successful (like the horrendous Black Scorpion saga).

Pro wrestling was gradually finishing up with Ole. He contributed to the WCW as best he could, staying employed as a trainer at the company’s Power Plant developmental school, but hated what he saw; Ole was among the first to publicly lay into Flair, whose career he helped build, as a routine man. In Inside Out, he wrote, “I was bothered by the fact that he did the same high spots in the same sequence in every match. He never mixed them up. Flair would do the same thing at the same point in every match.”

At this point, it would be possible to write off Ole as an example of pro wrestling’s troubled (yet successful) past. Yes, he was a tough guy and an asshole, but he was also one of the best workers and wrestling minds of the previous era. However, like McMahon, Ole’s work in the industry reminds us about much that was bad about that period.

For example, on race, Ole used part of Inside Out to discuss his frequent adversary Thunderbolt Patterson. After praising Patterson for his drawing ability, unbridled charisma, and knack for working the fans into a frenzy with his wrestling style, Ole then expressed his resentment toward Patterson for having the audacity to think he got over with the audience on his own merits. Ole then disclosed a face-to-face conversation he once had with Patterson. After admitting to Patterson that his act made money for the company, Ole revealed the racial motivation for always bringing Patterson back into the fold, phrased as a sort of backhanded compliment.

“The truth of the matter is, I was tired of your constant complaints, but I hired you back because you were black,” Ole recalled telling Patterson at the time. “If you had been white, I would have fired you in a heartbeat, and you would have stayed fired.”

Then, commenting outside of the bounds of the conversation, Ole reiterated the point.

“That was one of the times that I made an exception for someone who didn’t show up,” wrote Ole. “There’s the exception, and it was a big one—Thunderbolt Patterson. I hired him because he was black. If he had been white, he never would have had a job with me again. That’s the truth. But Thunderbolt never could quite understand that. He never will understand it. He thinks you’re being prejudicial for anything you do.”

Despite the animosity that Ole believed was present between himself and Patterson, both during their heyday and in the years that followed, longtime referee and manager Theodore “Teddy” Long characterized their relationship as being a generally friendly one, albeit one where Anderson felt free to let racial epithets fly in front of Patterson or any other Black wrestler, without any fear of reprisal.

“The only Black person that Ole really got along with was Thunderbolt Patterson,” stated Long. “He told me to my face. He said, ‘Teddy Long, you want to know why me and Thunderbolt make a lot of money? It’s because the whites want to see me whoop up on his nigger ass, and the niggers want to see him whoop up on my ass.’ That’s what he told me to my face.”

In fairness, Long’s characterization of the relationship between Ole and Patterson should probably be viewed in light of the power dynamic in play between boss and employee in an industry with very few bankable positions offered to Black performers. That dynamic added an extra element of competition to the equation, where Black wrestlers like Patterson were in competition to be the one Black babyface to be pushed in a territory over a set time period—a rule that would often see a territory highlight a single great Black star, like Bobo Brazil in Detroit or Junkyard Dog in Bill Watts’s Mid-South territory.

Ole tacitly confirms the racial dynamics that were at play in the booking, in as much as he lumps his booking of all the Black wrestlers together within one chapter. Moreover, he wrote statements along the lines of “Tony Atlas came down with that Thunderbolt Patterson attitude,” either the spirit of Ole’s notion that Atlas couldn’t understand that he was only employed because he was Black, or because Atlas was, in Ole’s view, overly sensitive with respect to race. In the framing of the passage, it’s difficult to determine which meaning Anderson ascribes to Atlas. However, if Atlas harbored any particular resentment resulting from racist barbs from Anderson, he doesn’t declare so in his own autobiography, Atlas: Too Much… Too Soon.

“When I did something stupid, Ole Anderson would say, ‘You dumb, nigger!’ I never paid any attention to it,” wrote Atlas.

Also weighing in on Anderson’s conduct was Olympic weightlifter Ken Patera, who was an onlooker to a verbal altercation between Anderson and “Big Cat” Ernie Ladd. It just so happened that Ladd was booking the territory at the time, resulting in one of the few alleged altercations during which Anderson fired racial salvos at someone who at least temporarily outranked him in the locker room.

“Here’s Ole Anderson at 5-10, and here’s Ernie Ladd at 6-10. Ole’s looking up at Ernie and said, ‘You fucking nigger! You don’t even know how to put matches together! What the hell’s goin’ on here?!’” described Patera. “Ernie looks at him and says, ‘What are you talkin’ about? This is a better program than you ever put together!’ So Ole looked at him and said, ‘You dumb fucking nigger! You think you can put matches together because you graduate from Grambling College? Anyone can graduate from Grambling College because it’s a nigger college!’”

Immediately after narrating a scene that would be wholly unthinkable in a modern working environment, Patera immediately defends the conversation as a byproduct of the era and environment in which it transpired.

“Ernie was laughing right along with everybody else in the locker room,” insisted Patera. “Back in the ’70s that didn’t bother white people, it didn’t bother black people. Now it’s a big deal.”

Absent from these scenes is any context for exactly why someone like Ladd might have been motivated to hastily disregard such a remark. Who could Ladd have complained to in a monopolistic business in which 100 percent of the North American territories were White-owned, and most wrestling territories operated south of the Mason-Dixon Line?

Of course, in a business that allotted Black wrestlers favorable positions on the basis of one per territory for a set number of months, would raising a stink of any kind be worth the potential backlash of being categorized as difficult to work with? To what extent was the response of Black wrestlers to shut up and soldier on in the face of Anderson’s insults simply owed to a pragmatic recognition of the power dynamic of the territories? (Thunderbolt Patterson was ultimately blacklisted from the pro wrestling industry after speaking out on the racism he experienced, and for trying to unionize wrestlers.)

Ole articulated his position best when he said of Patterson, “I hired him because he was black,” then stating that he endured the annoyance of Patterson because of his contribution to the territory’s bottom line. It was because Anderson understood the financial value of a Black presence. His ability to overlook personal prejudice and develop Black talent for profit hardly makes him a hero any more than an enslaver should be praised for teaching an enslaved person how to steer a plow.

At the same time, a thread of utilitarianism runs through all of Anderson’s professional dealings, regardless of a wrestler’s race. Anderson stated in the very same chapter, “I didn’t like very many people anyway. I was never close to a lot of people … If they were talented and worked hard, I liked them.”

When evaluating Ole Anderson’s complex legacy, we should recognize the nuanced and often troubling dynamics that characterized the wrestling industry he helped build. Ole’s interactions with Black wrestlers, such as Thunderbolt Patterson and Tony Atlas, underline a deeply ingrained culture of racial prejudice that was not unique to him but was rather indicative of the broader environment in professional wrestling. It was an exclusionary culture long dominated by prominent figures like McMahon and Flair, whose actions and attitudes toward women represent another deeply unsettling aspect of the industry. Although he, McMahon, and Flair were indeed birds of a different feather when it came to showmanship and presentation, they all navigated the same turbulent skies of professional wrestling’s past.

It may be true that an untoward artifact of wrestling’s past has been acknowledged as an aspect of its culture at that time. That doesn’t mean it wouldn’t have been a disgusting or rotten outlier compared to the world and era in which it existed. Simply because a wrestler’s in-ring conduct was worthy of praise doesn’t shield their base conduct outside of the ring from historical critique or criticism.

Oliver Lee Bateman is a journalist and sports historian who lives in Pittsburgh. You can follow him on Twitter (@MoustacheClubUS) and read more of his work at oliverbateman.com.

Ian Douglass is a journalist and historian who is originally from Southfield, Michigan. He is the coauthor of several pro wrestling autobiographies, and is the author of Bahamian Rhapsody, a book about the history of professional wrestling in the Bahamas, which is available on Amazon. You can follow him on Twitter (@Streamglass) and read more of his work at iandouglass.net.