Update, Feb. 4, 2024: This piece was updated after publication with more information about Virgil’s age.

While it has never been remembered as “the belt shot heard ’round the world,” the crowd erupted just the same when Virgil struck his soon-to-be-former employer, “Million Dollar Man” Ted DiBiase, with the Million Dollar title belt. The first strike, an accident, occurred during their tag team match at the 1991 Royal Rumble against Dusty Rhodes and his son Dustin, the latter of whom moved out of DiBiase’s grasp just in time for Virgil to land a clothesline on his boss. The mistake, occurring after months of miscommunication between the two, earned Virgil a beatdown from DiBiase, who still secured a rollup pinfall on the American Dream. Post-match, DiBiase berated Virgil, calling him an “idiot” before barking at Virgil to grab the Million Dollar title and put it around his waist. You know what happened next: Virgil indeed retrieved the title, only to bash DiBiase in the skull, giving any fan who daydreamed about ditching their current job the perfect payoff. Virgil’s active career in the squared circle lasted another nine years, yet this may have been the biggest moment in his professional wrestling career.

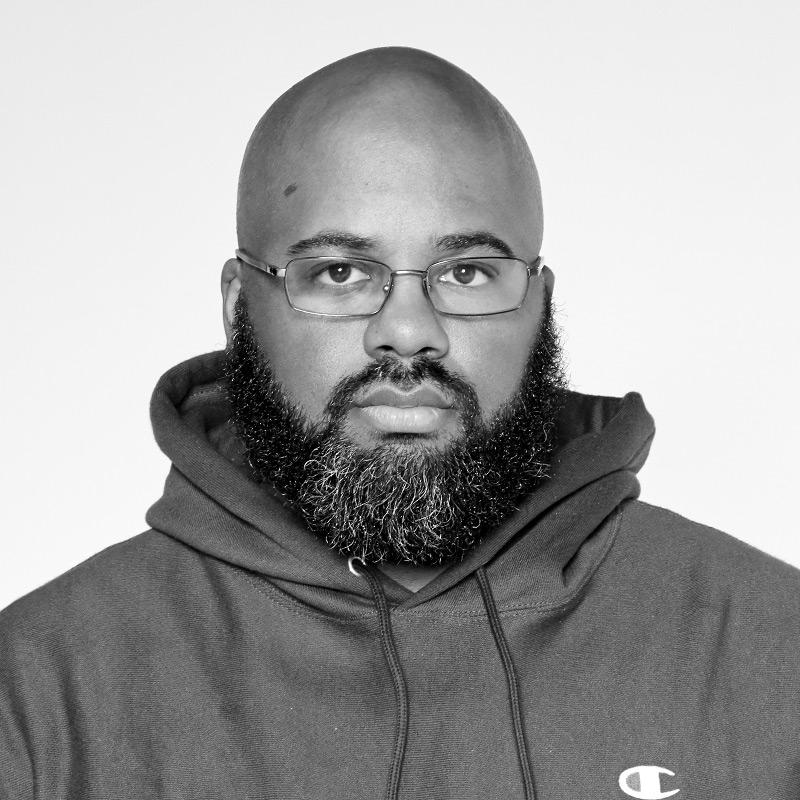

Mike Jones, best known as Virgil, died this week at the age of 72. Virgil was DiBiase’s manservant—a term from the 14th century that, even at the time, felt about as close as you could get to saying “slave” without actually saying it. Jones’s stint as Virgil during the latter part of WWE’s late-1980s boom is memorable for the sheer fact that the company’s popularity meant that anyone associated with DiBiase—a character long speculated to be based on Vince McMahon himself, who was thought to have bankrolled a luxury lifestyle for DiBiase, with a manservant as a bonus—was destined to be the set-up guy for DiBiase’s schemes. Yet for some fans, cheering for Virgil was all we had.

Virgil the character wasn’t supposed to be the “star,” but Mike Jones the man made it hard to take your eyes off of him during a time when there were truly few Black professional wrestlers on screen during one of the biggest periods for the sport.

In the modern era, we always think about what the wrestlers had to overcome in real life to get where they are. Through that lens, every popular Black wrestler prior to the modern day was a massive success story. And considering where he started, Virgil was an absolute icon.

Mike Jones entered the World Wrestling Federation in a similar fashion to many of McMahon’s new hires in the 1980s. He’d first found moderate success in Memphis’s Continental Wrestling Association as Soul Train Jones, holding the AWA International Heavyweight Championship and the AWA Southern Tag Team Championship (with Rocky Johnson). On one occasion, Jones even challenged AWA mainstay Nick Bockwinkel for the AWA World Heavyweight title. McMahon acquired talent from all across the territories, and in 1986, Jones made his way to WWF, first under the name Lucius Brown. Then, in the summer of 1987, WWF introduced the first vignettes of Ted DiBiase under his new “Million Dollar Man” gimmick, with Jones in tow as his bodyguard, Virgil.

The Million Dollar Man was a pure heel, the kind of jerk who buys out the pool for a day just so he can have it all to himself. One memorable segment found DiBiase and Virgil holding a basketball (“Poor man’s sport, basketball, right Virgil?” DiBiase asks rhetorically) and presenting a challenge to a young Black fan in the crowd: Dribble the ball 15 times in a row, and you can win $500. (“I can tell by looking at you that you can use a lot more than 500 bucks!” DiBiase cracks.) Shawn, shy but determined to win that money, got 14 successful dribbles before DiBiase kicked the ball away.

The moral of DiBiase’s story? “When you don’t do the job right, you don’t get paid.” For a while, Virgil did the job right, putting himself at DiBiase’s beck and call and even having to wrestle some of DiBiase’s foes before they got a chance to face the Million Dollar Man. Speculation has always surrounded what Jones’s job actually was: Was he just portraying a manservant to an exceedingly rich asshole, or was there a more elaborate motivation for the gimmick?

The rumor has always been that DiBiase’s hired help was more of an elaborate dig at “The American Dream” Dusty Rhodes, a humongous star (and booker) of WWF’s opposition, the National Wrestling Alliance, particularly during the Jim Crockett Promotions era. Rhodes’s real name is Virgil Runnels Jr.—was it a coincidence that Jones’s character shared Rhodes’s real first name, or that DiBiase’s finisher was known as the “Million Dollar Dream”? McMahon has never gone on record confirming this, but it raises the question: How much faith could the promoter of the top federation in the country have in an employee if their entire gimmick is a lightly veiled joke on the opposition?

Or maybe a joke on the audience, especially viewers like myself, who would scan TV Guide every week to program the VCR for whenever a show with “wrestling” in the title aired. At that time, there weren’t many Black faces in wrestling for Black fans to relate to, especially ones in actual title contention. Bad News Brown would hold his fist high in the air, but he was never a serious contender for the WWF Championship, even as a legit judo bronze medalist in the Olympics. Koko B. Ware was a high-flying sight to see, and Junkyard Dog reminded me of my uncles. When you consume pro wrestling on a massive scale, you gain an understanding of who is going to be advancing to the main event and who will be devoured on their journey. It didn’t take a rocket scientist to see that Black talent could only get so far, especially in the WWF. (This was the time before Ron Simmons’s five-month WCW World Heavyweight Championship reign, which was such an anomaly that it was almost nine years before another Black wrestler, eventual WWE Hall of Famer Booker T, would hold the title.) A Black man getting a big win wasn’t common in the WWF, which helped make the progression of Virgil and DiBiase’s story much more satisfying.

Fast forward to the 1991 Royal Rumble, which marked Virgil’s official split from DiBiase after blasting his boss with the Million Dollar title following the match. (Yes, DiBiase was the kind of jerk who couldn’t win the actual world title, so he had his own made.) And even if the crowd reaction wasn’t Austin-McMahon levels of pandemonium, the tension between these two had been building for some time; spectators were ready to see Virgil lash out at DiBiase after all this time. This set the stage for Virgil to … be overshadowed by “Rowdy” Roddy Piper, who “mentored” Virgil leading up to the latter’s countout victory against DiBiase at WrestleMania VII. Virgil won the Million Dollar title at SummerSlam in August, but his Million Dollar title reign didn’t last long, as he would drop the belt back to DiBiase in November before feuding with DiBiase and the Repo Man for months thereafter. His WWF career was downhill after that, with the biggest highlight of the next three years of his in-ring career being the candy cane-esque gear he started wearing in 1992.

Now, there are no delusions here: Mike Jones was far from an elite wrestler, and his coworkers and wrestling fans alike have never been afraid of letting that be known. Without a Performance Center or developmental brand like NXT, most wrestlers learned on the road, where up-and-comers took their bumps and perfected their craft. If your job is to be some rich guy’s silent servant, how can you then be expected to cut quality promos? When you watch this video, does it sound like Virgil just got thrown in front of a camera after years of not speaking publicly? Because that’s exactly what happened.

Even if you want to argue that at least Virgil was employed for a good eight years with the WWF during a period of massive growth, that doesn’t mean he received any push to become a bigger (or at least better) performer. Virgil lost 86 percent of his bouts in 1988; in 1989, he lost 100 percent of his matches. (There were only four, but still.) Virgil was never seen as anything more than a servant, and when that job was done, there was no real investment in him as a performer or character.

After his time with the WWF ended, Jones would continue to ride the Virgil wave, heading over to the burgeoning independent National Wrestling Conference, which went from highlighting popular talent from Extreme Championship Wrestling to attracting former WWF stars like the Ultimate Warrior and, yes, Virgil. With NWC, Virgil was involved in a controversial angle where a white wrestler known as the Thug brought an individual dressed like a member of the KKK to the ring in a match against Virgil. During the bout, Thug’s associate revealed himself to be former WWF star Jim “The Anvil” Neidhart; Thug and Neidhart proceeded to hang Virgil from the ropes with Neidhart’s white robe. In a profession where bookers openly admit to allowing only one Black performer to be the star of a territory at a time, there were only so many options for an undervalued performer like Virgil.

Maybe that’s why, when WCW called in 1996, Mike Jones answered. He was more than ready to join the nWo faction as “Vincent,” their “head of security”—a jab back at Vince McMahon for “Virgil.” And of course the nWo’s head of security would be first in line to get demolished by the group’s detractors. It was Virgil all over again—he’d even reunite with DiBiase, who was now acting as a manager in WCW. Many of the old WWF hires were just playing the hits in this era of WCW, and Vincent was right there, ready to again take the beating for someone higher up.

Throughout his travels, Jones maintained his sense of humor. After his time with the nWo fizzled out, he joined the West Texas Rednecks stable, going by Curly Bill and embracing the anti-rap stance of the group. Once again, he played up a gimmick that didn’t reflect his real self, without breaking character.

Virgil spent the rest of the ’90s in WCW, taking on a few more gimmicks before retiring from in-ring action in 2000. In 2006, he started making appearances again both in the ring and at wrestling conventions, which sparked Virgil’s second life. No, we’re not talking about that month he spent in WWE as Ted DiBiase Jr.’s manservant back in 2010, or Soul Train Jones’s sporadic appearances in All Elite Wrestling. We’re talking about the Lonely Virgil craze, in which wrestling fans shared photos and stories of meeting Virgil at conventions and observing how lonely Virgil looked compared to his more famous peers. Jones’s middle name should have been Hustle; the man was notorious for his pursuit of the almighty dollar. The infamous tales of fans meeting him in person painted a picture of a desperate man who was seemingly willing to do anything for a buck. (Do we have to remind you about the Thug-KKK incident in NWC?) Even if you want to make fun of that infamous “Virgil Wrestling Superstar” image, you can’t take this away from Mike Jones: During the WWF’s boom, Virgil was one of a handful of Black faces on WWF television. He earned that title of “superstar,” even if he wasn’t given any opportunities to truly become one.

Is there a world in which Virgil could have become an R-Truth or the Miz, performers who have touched the main-event scene but will likely be remembered best for their character work and longevity in the middle of the card? Does that sound preposterous? It sure sounded preposterous when Mike “The Miz” was terrorizing his Real World housemates with his turnbuckle dreams. And when he finally got to WWE, the Miz still had a long way to go; he was kicked out of the locker room while he was coming up. But two years after his main roster debut, he received multiple Most Improved awards for his work; two WWE Championship runs, eight Intercontinental title reigns, and two United States title runs are the highlights of the gold Miz has held since WWE started investing in him. Could Virgil have been a multi-time Intercontinental champion in the Bret Hart/Mr. Perfect era? A McMahon push wouldn’t have turned him into Bryan Danielson in the skills department overnight, but Virgil could’ve been somebody’s tag team partner, possibly vying for the tag titles. Right?

Probably not. It was an evolving time, and issues of race in America were heated; Virgil’s split from DiBiase came a year before the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Virgil’s role as a “manservant” for DiBiase during that time hit a level of offensiveness that McMahon was too oblivious to notice or to recognize as an issue. This WWE was not the WWE that would have had Virgil move on to bigger achievements after sticking it to the man. It’s difficult being a true “people’s champion” when the establishment wasn’t built to even notice that potential in certain performers.

For a moment, Virgil was the most popular Black wrestler in the world. He tired of the years of flak he took from his employer, stuck it to him, and seized his most prized possession for a time. Virgil fought his hardest to defy the odds, but the system wasn’t set up for him to advance. Thankfully, we’ve moved past these obstacles—the pandemic era of WWE programming alone saw Black superstars like Bianca Belair, Bobby Lashley, and Big E having credible world championship reigns. But for that brief moment in 1991, Virgil cracking DiBiase with that fugazi title belt was enough for us.