Not so long ago, Dune was dormant IP. In March 2011, Paramount’s option on the classic sci-fi novel expired after a failed four-year attempt to make a movie adaptation. “Right now, Dune has no commitments or attachments,” said producer Richard P. Rubinstein, who had held the rights to Frank Herbert’s bestselling book since 1996. Rubinstein was willing to try again and looked for a long-term relationship, but Dune’s free-agent phase would persist until Legendary Entertainment acquired the rights in November 2016.

Plenty of production companies must regret not pouncing on the property when it was available. Unlike the Kwisatz Haderach, though, Hollywood deal brokers can’t foresee all possible futures, and thus the valuable-in-retrospect rights lay fallow for five-plus years. Not every previous screen adaptation of Dune had been disastrous: 1992’s Dune II: The Building of a Dynasty was a revolutionary real-time strategy video game, and Rubinstein’s two Emmy-winning miniseries for the Sci-Fi Channel in the early 2000s were well regarded enough. But the breakout didn’t come until Legendary pulled a Paul Muad’Dib and charted a narrow way through the thicket of developmental problems that had derailed Dune adaptations for decades: Hand Herbert’s text to undefeated director (and Dunehead) Denis Villeneuve and give him the resources and screen time to do justice to the story.

That approach has paid off: Villeneuve’s second Dune movie, Dune: Part Two, won over critics, impressed the public, and grossed $82.5 million in North America and $182.5 million worldwide (not including China or Japan) in its opening weekend. That doubled the initial take of Villeneuve’s first Dune film, which went on to gross $433 million globally after launching in theaters and on HBO Max simultaneously in October 2021. Part Two may more than double that total, which would make it one of 2024’s highest-grossing releases. The arid landscape of Dune adaptations has become a green paradise.

Potentially, at least. Reports of Legendary’s “comprehensive plans” for a Dune multimedia empire sounded speculative and pie-in-the-sky in 2019, when Dune’s adaptation prospects were still stained by both David Lynch’s 1984 critical and commercial flop and other adaptation attempts that never made it to screens. In the wake of the new films’ success, that vision of a long-lasting, lucrative, trans-media franchise is starting to coalesce. At least one more movie is likely on the way. A small-screen prequel series about the Bene Gesserit, Dune: Prophecy, is scheduled to premiere on Max later this year. One video game, a new RTS called Dune: Spice Wars, came out last year, and the trailer for another, an open-world survival MMO called Dune: Awakening, dropped this week. Accompanying those projects are all the off-screen trappings of major sci-fi and fantasy franchises: comics, board games (a Dune tradition), LEGO sets, etc.

In 2020, the year before Villeneuve’s Dune debuted, longtime Dune fans Abu Zafar and Leo Wiggins started Gom Jabbar: A Dune Podcast, in anticipation of an uptick in the series’ popular profile. Even they underestimated the degree to which Dune would soon enter the zeitgeist. “Sci-fi fans have always loved Dune,” Zafar says. “But now we’re seeing everyone love Dune. … It’s been a sleeping giant just waiting to take over the world. Denis Villeneuve came along and woke up the giant.”

After all the filmic false starts, the franchise has shed a great burden, like Baron Harkonnen when he wears his suspensors. The series seems to be ascending to the IP pantheon and belatedly taking its place alongside the other marquee mega-franchises that Dune directly influenced or indirectly rubbed off on (Star Wars foremost among them). It’s only fair for the series that inspired so many others to take its turn on the throne. But will the expanded Dune universe (Dune-iverse?) last as long as Leto’s Peace, or is the franchise’s reign destined to be brief? Let’s snort some spice for prescience and ponder, point/counterpoint-style.

Point: There’s so much source material.

It’s a great story … but does it scale? Fans might not be asking that, but the bean counters are. And, for better or worse, Dune does.

Dune alone yielded two movies with a combined running time of more than five hours—and that was after some substantial story compression. Herbert wrote six books in the series, some of them almost as long as (or even longer than) the first one. In theory, that’s enough to keep moviemakers busy for years to come. And when those narrative veins are tapped out, there are many more to mine: Herbert’s son Brian and Kevin J. Anderson have cowritten 17 (17!) novels set in the world of Dune—some prequels, some sequels, and some stories that fill in the gaps between Frank Herbert’s books. (Prophecy may or may not be based on one distant prequel, Sisterhood of Dune.) Then there are the novellas and short stories.

To establish a thriving franchise, the content must flow. Not too freely, as the recent Star Wars and MCU slowdowns have illustrated, but steadily enough to keep people in the tent. Now that they’ve finally caught on, adaptations of Dune need never end.

Counterpoint: So much of that material is … strange.

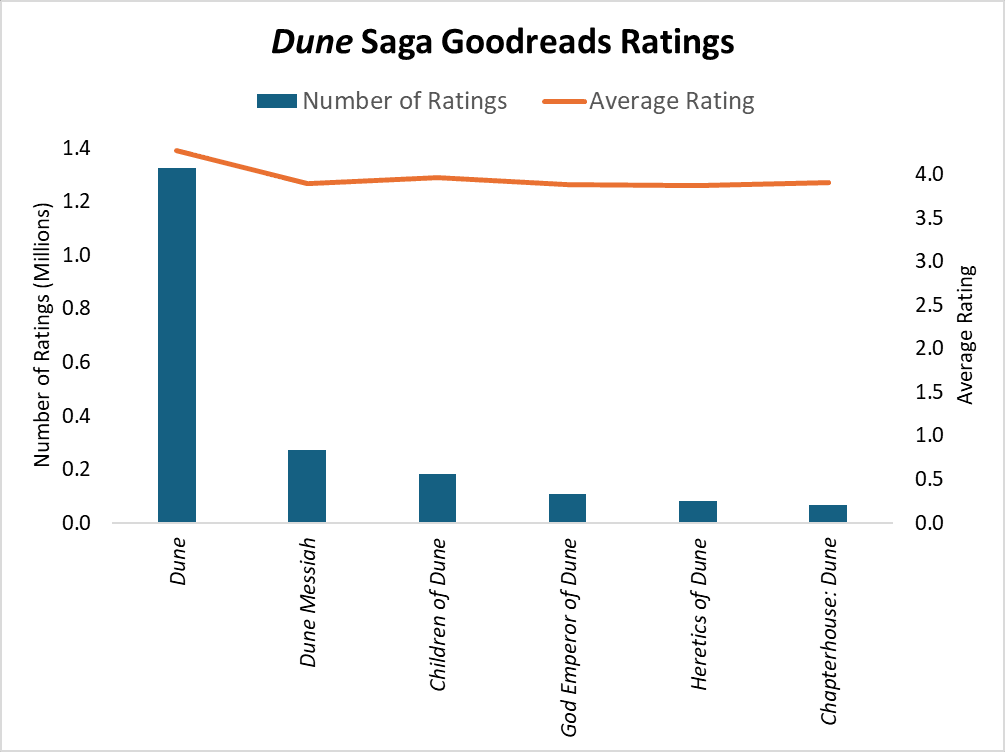

Dune may be a masterpiece, but the series gets progressively less accessible as its lore accumulates. The number of Goodreads ratings gives us some indication of the precipitous decline in popular awareness of the series beyond the first book.

Granted, that first book is generally regarded as the bestselling sci-fi novel ever, so the post-Dune drop-off almost has to be steep. Plus, the sequels haven’t gotten the big-screen adaptation treatment yet. Still, that’s quite a plummet in popularity, even compared to other series of comparable length. The subsequent books aren’t bad; they all hover around a respectable average rating. It’s just that they’re “more … esoteric,” as Villeneuve diplomatically put it. Less diplomatically, they develop in a Weirding Way. They also end in unfulfilling fashion, as Frank died less than a year after the publication of Chapterhouse: Dune, with some significant story lines still unresolved.

After the first few books, the degree of adaptation difficulty really ramps up, thanks to titanic time jumps, decreased action, an enormous amount of inner monologue, and more. It’s been quite a while since my full-series read, but take it from a massive Dune fan: “Once you get into the latter books like God Emperor of Dune and beyond, the story truly takes the weirdest (and horniest) of turns, and some of the ideas it explores start to become problematic,” Zafar says. Horniness alone needn’t be bad, but in this case … well, here’s a sample sentence: “There was an adult beefswelling in his loins and he felt his mouth open, holding, clinging to the girder-shape of ecstasy.” (Beefswelling.) And that’s from Book 3! Zafar continues, “Those later books in the series are a quagmire and are impossible to adapt in a way that makes for a hit blockbuster film and also stays true to the source material.”

Oh, and those almost innumerable Brian Herbert collabs? Their quantity denotes a lack of care in comparison to his father’s more moderate output. On the one hand, Brian’s liberal approach to building the Dune corpus—including coauthoring two novels that supposedly drew on his dad’s notes to take the place of the planned seventh and final Dune book that Frank was working on when he died—means that there are fewer hurdles to expanding the Dune-iverse than there have been with properties such as Game of Thrones, Harry Potter, or The Lord of the Rings. On the other hand, there’s something to be said for quality control. “Brian has not exactly treated his father’s work with the same reverence that Christopher [Tolkien] gave to J.R.R Tolkien’s writings,” Zafar says. “As fans, we have many issues with Brian’s steering of the Dune ship, and his refusal to allow other creatives to add to the universe with original stories and art.”

Frank’s elder son’s decisions are extra relevant to Dune’s franchise future because Herbert probably hasn’t handed over the keys to Arrakis. Trade reports in 2016 suggested that Legendary had acquired the rights to Dune the novel, not Dune the all-encompassing IP. If that’s the case, then further Dune development would require the OK of Brian Herbert, and maybe additional negotiation. Legendary’s CEO, Josh Grode, lent credence to that notion this week when he said that for a third film to come to fruition, “We have to have all creative stakeholders aligned and support the vision.” In response to an emailed question about the status of the rights to the rest of the saga, Frank’s grandson (and Brian’s nephew) Byron Merritt, who’s credited as an executive producer of both of Villeneuve’s films and Prophecy, wrote to me that “these kinds of deals are not made public so we cannot comment on them.” Neither Legendary nor the literary representative for the Herbert estate replied to similar inquiries.

Point: Villeneuve never misses.

Fine, the rights situation is somewhat murky. No matter: If additional deals are required, it seems safe to assume they’ll get done. Shortly before Villeneuve’s first Dune movie premiered, WarnerMedia Studios and Networks chair and CEO Ann Sarnoff said, “Will we have a sequel to Dune? If you watch the movie, you see how it ends. I think you pretty much know the answer to that.” If you watch Dune: Part Two and see how it ends—and also see the reception and earnings—you pretty much know the answer to whether the sequel will get its own sequel.

Villeneuve has been talking about his intention to adapt Frank Herbert’s second book, Dune Messiah, as his third Dune movie since before the first film came out. Last December, he said the script was almost finished, and last week, composer Hans Zimmer said he’s already working on Messiah’s score. As Grode also said, addressing the potential for a third act of Dune, “If Denis gets the script right and he feels that he can deliver another experience on par with what we’ve just completed, then I don’t see why not.” The more bank the latest movie makes, the more we can bank on another one.

And after that? Well, Dune was once considered unfilmable, and look how that turned out. Maybe the more batshit books will be salvageable too. Wiggins, Zafar’s cohost, is more confident than Zafar that the weirder Dune novels could be overhauled, modernized, and made suitable for the screen. And as long as Villeneuve is at the helm, Wiggins isn’t worried: “He’s proven his vision, and in Denis we trust.”

Counterpoint: Villeneuve might be missed.

Except there is some cause for concern, because as Wiggins is well aware, Villeneuve wants to stay at the helm for one more movie, at most. “Dune Messiah should be the last Dune movie for me,” he told Time Magazine earlier this year, after previously saying to Empire, “If I succeed in making a trilogy, that would be the dream.” Dune Messiah, which completes Paul’s arc, is a much more compact book than Dune. If Villeneuve adapts it, he could declare his mission accomplished and walk away before the going gets gonzo in subsequent books. “I think he’s smart enough to let someone else make the mistake of trying to adapt them,” Zafar says.

If Dune Messiah does well, it’s almost certain that someone will stick their hand into that potentially painful trap—and whether the series escapes it unscathed could determine Dune’s long-term trajectory. As Wiggins notes, the acclaim for the new Dune duology has freed the IP from the prison of its past: “If a new Dune thing comes down the pipeline in 10 years, it won’t be greeted with ‘Oh, that Lynch movie from the ’80s?’” But the expectations summoned by a blockbuster can be as much of a millstone as the doubts caused by a bomb. Lynch’s Dune made it harder for Villeneuve’s to get made; Villeneuve’s Dune may make it harder for the next incarnation to satisfy freshly minted fans. “The success and staying power of the broader IP is going to be determined by the quality of non-Denis projects,” Wiggins says.

The first of those scripted projects is Prophecy, which has already endured a good deal of creative turmoil. Villeneuve was supposed to direct Prophecy’s pilot, but his work on Part Two prevented him from doing so. In addition to multiple departures of directors and showrunners, the series has weathered casting swaps, a change in composer, and a new title to boot (changed from Dune: The Sisterhood). The game of musical chairs only adds to the pressure on Prophecy, whose performance may be scrutinized as a bellwether of post-Denis Dune. What if it feels like a ghola of Villeneuve’s Dune instead of the genuine article? “Audiences (and the financiers watching from the shadows) will inevitably compare their experience watching it to the films, and if it’s bad, Dune will be more cemented as ‘the thing that’s good if Denis is doing it,’” Wiggins adds.

Point: Dune is too good to go away.

OK, but come on: Have you seen Part Two? How wholeheartedly audiences have embraced it? How hungry they are for more? The franchise may have gone 0-fer in its first few adaptation attempts, but like a skilled slugger who hit into hard luck, Dune was due. Maybe this isn’t a hot streak—it’s the series’ true talent finally made manifest, and a slump can’t kill its momentum any more than a stab by Feyd-Rautha could kill Paul. Dune has sandwormed its way into our lives to stay.

Counterpoint: On-screen, it’s still a fledgling franchise.

The Fremen name for sandworms, Shai-Hulud, derives from the Arabic for “thing of eternity.” Once a worm is mature, it’s almost indestructible. But as Part Two taught us, a baby worm can be drowned by one woman. Dune’s origins are old, but it’s basically a baby as a box-office force.

Yes, Dune had a huge opening—which was roughly half as huge as the opening of 2019’s Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, the much-maligned coda to the Skywalker saga. Dune may be “Star Wars for adults,” as Villeneuve once said—echoing Frank Herbert’s mid-’80s dismissal of George Lucas’s series, which liberally lifted from his own—but the movie version didn’t capture the hearts of today’s adults when they were kids. The franchise has graduated from cult status, but it’s not yet unstoppable, and it could still stray from the Golden Path.

The combined brilliance of Frank Herbert and Denis Villeneuve was a winning formula, but a lot of other factors conspired to make Part Two a sensation. A clear runway on the post-strikes schedule. A paucity of Star Wars and superheroes at the multiplex, and a hunger for “fresh” IP. (Which is several decades old, in Dune’s case, but so what? We’re in a Barbie world.) Some of the stars’ publicity boosts since they were cast. The three-hour Oppenheimer’s shifting of the movie-length Overton window. The popcorn buckets. Maybe there’s an alternate timeline where Dune lands like Foundation, an even older, formerly “unfilmable” sci-fi franchise that’s finally flourished on-screen without making much of a mark on the culture.

In Part Two, Paul passes a series of tests to become a full-fledged Fremen. Dune adaptations face two tests now as they pledge the franchise fraternity. First, Prophecy has to succeed, which could be a stepping stone to a topical series about the Butlerian Jihad—demonstrating that Dune doesn’t need an Atreides—or an animated take on Jodorowsky’s Dune. Then, the movies must maintain their momentum during what could be a lengthy break before Dune Messiah. Villeneuve wants to make another movie—a “small movie,” maybe, though I’m rooting for Rendezvous With Rama—before he returns to Dune, both to give himself a break and to let Timothée Chalamet age into the older Paul of Dune Messiah. “For now, I’ve had my share of sand and I would love to take a little break from Arrakis before going back, if ever I go back,” Villeneuve told Uproxx last month.

Warner Bros. Discovery, which coproduces and distributes Dune, is all in on primo IP: In a November 2022 earnings call, president and CEO David Zaslav bragged about the conglomerate’s lineup of “brands that are understood and loved everywhere in the world” and vowed to “focus on franchises.” On last year’s earnings call, he lamented, “a lot of our most popular IP has been underused” and pledged to “maximiz[e] the value of our blue-chip franchises.” But maximizing value doesn’t always mean maximizing the number of prequels, sequels, and spinoffs. Maybe Dune seems so exciting because we haven’t had time to get tired of it. A little break from Arrakis is risky for franchise building, but so is too much time on Tatooine.

“It’s clear Dune’s ability to captivate as an IP was undervalued since (and perhaps due to) Lynch’s divisive adaptation,” Wiggins says. Hollywood won’t make that mistake again. But it might make the mistake of following too little Dune with too much. Overwatering this seedling of a forever franchise could be the little-death that brings total obliteration. “We’re about to be buried … up to our stillsuit nose plugs in Dune content,” Zafar says. With any luck, we won’t have to hold our noses to keep finding that fun.