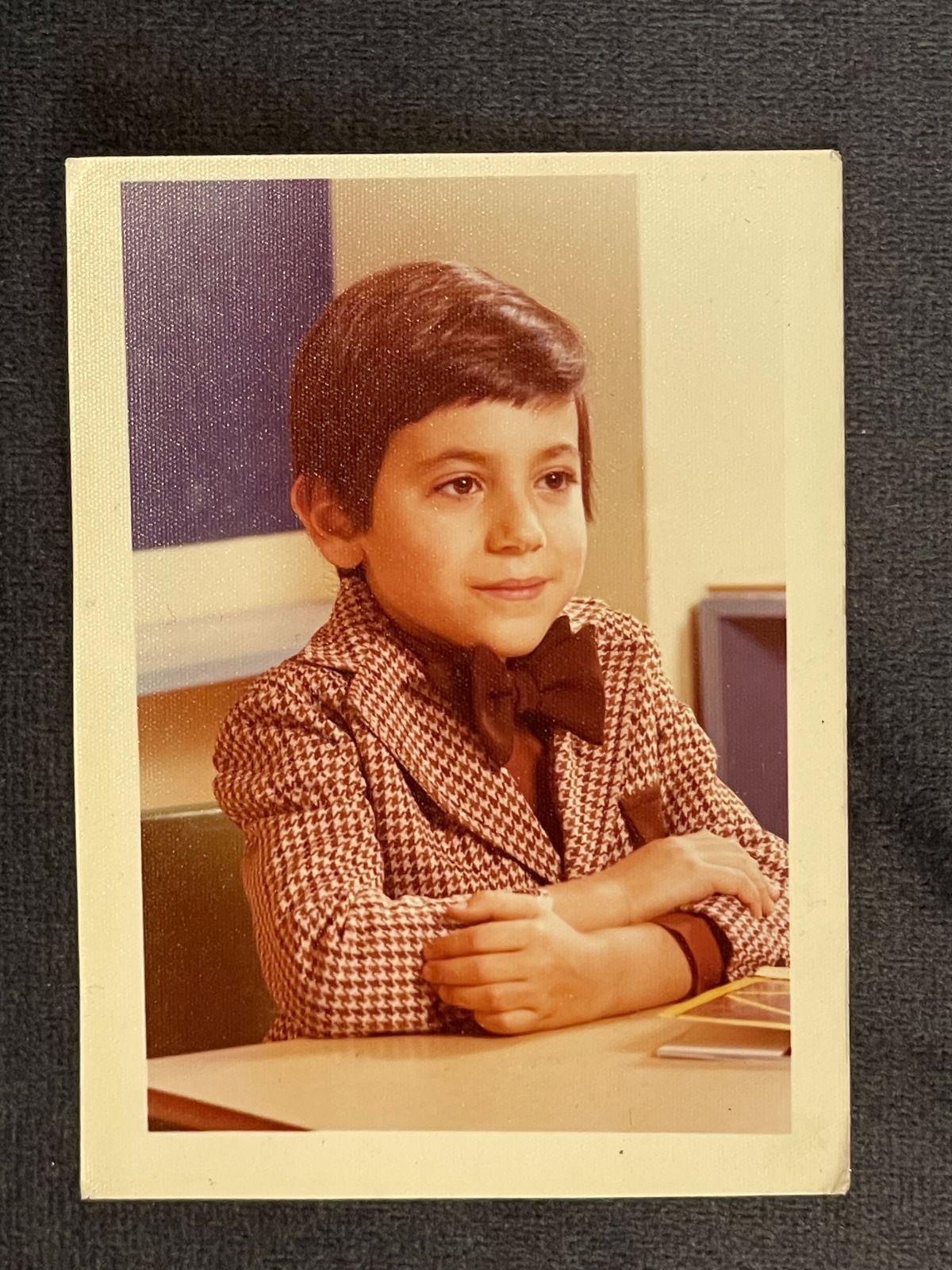

Ian Eagle got his big break in 1975. It came not in a TV booth but in a nightclub in the Catskill Mountains. Ian wasn’t wearing a network blazer. He wore a suit made of a green corduroy. Ian was 6 years old.

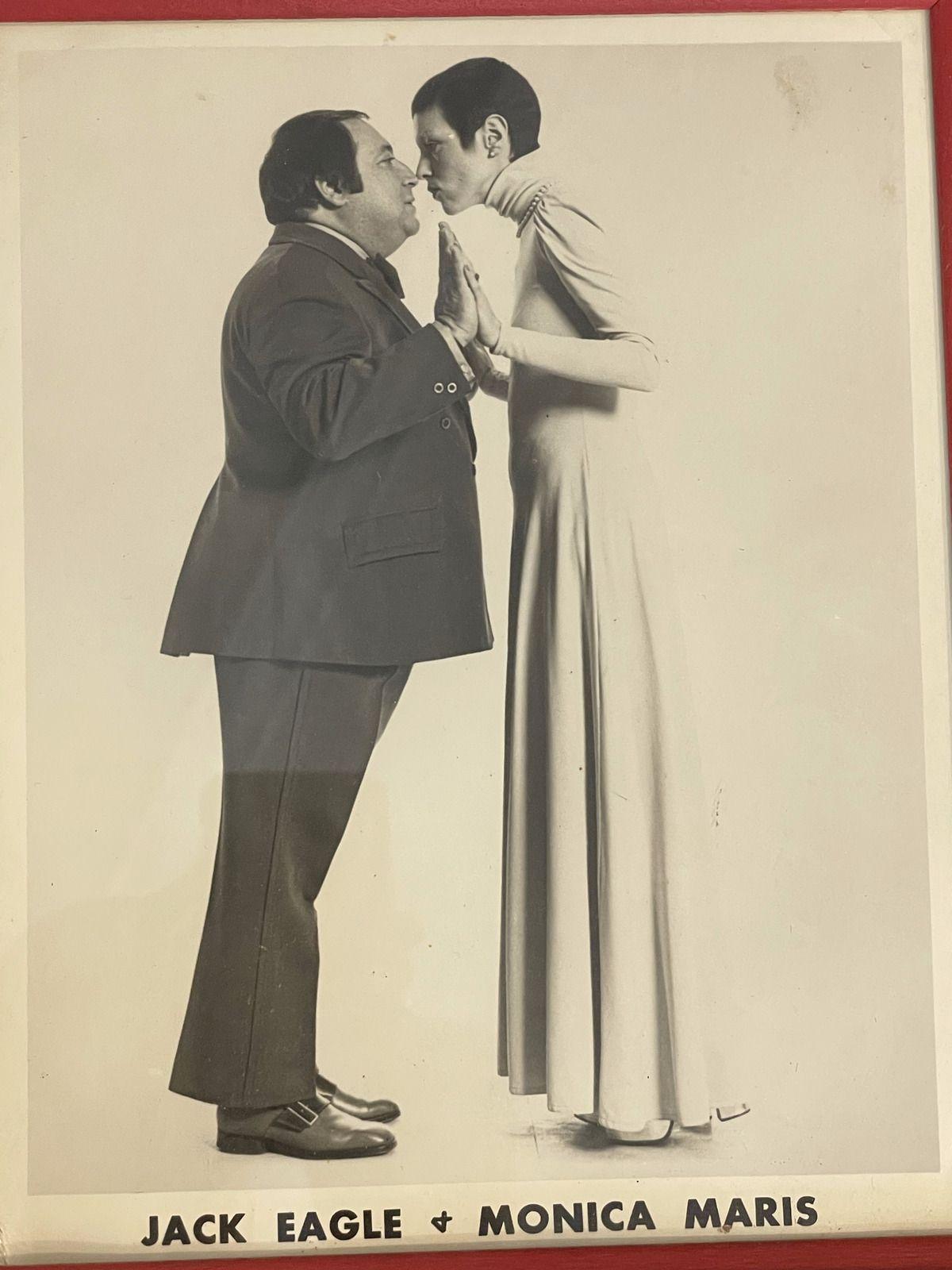

Ian’s parents were scuffling entertainers who took their act on a circuit of Catskills resorts. His mom, Monica Maris, came onstage first. Monica was a tall, skinny singer who always finished with her showstopper, “Over the Rainbow.” Eagle’s dad, Jack, came out next. Jack was a comedian who told jokes about his stomach. “He was short and fat, and he used it,” said Ian.

At the end of each show, they stood before the audience together: Monica at stage right, Jack at stage left. After the crowd took them in, Jack exclaimed, “We look like the number 10!” Ba-dum-sssss.

One night, in 1975, Jack and Monica said they had a surprise for the audience. Ian had been working on some celebrity impressions. He wanted to please his parents, and they figured he should have no problem performing in a nightclub. “They told me that it would work,” said Ian. “It was that simple. There was no sense of apprehension. Nothing.”

Ian stood in the wings of the nightclub stage long past the bedtime of a typical 6-year-old. Around 11 p.m., he walked out wearing what his dad called a “handsome suit.” “I had the look of a ventriloquist’s dummy,” said Ian. He imitated Howard Cosell, W.C. Fields, and Muhammad Ali. He got laughs.

“It definitely planted a seed in my head,” said Eagle. “That this is not that intimidating. That it’s not abnormal to talk to an audience.”

This month, Eagle has been nudged into the spotlight again. CBS and Turner picked Eagle to be the new lead announcer for their men’s NCAA tournament coverage. As part of the gig, Eagle will call the Final Four with Bill Raftery and Grant Hill. A showbiz veteran would also recognize that Eagle, at the ripe age of 55, has finally become the headliner. He is a no. 1 announcer.

For the better part of a decade, Eagle was a no. 2 announcer. He called the second-best NFL games for CBS and the second-best NBA games for Turner. At the 2021 Super Bowl, Eagle went to Tampa as the backup for Jim Nantz on TV and Kevin Harlan on the radio.

[Eagle] never, ever said, ‘Boy, someday I’d like to …’ He was more in the moment. This is what I’m doing. I’m doing the best I can. And, hopefully, people will notice.Bill Raftery

Being a no. 2 announcer is a great job in its own right. But Eagle’s colleagues thought the designation undersold his talent. Eagle can call a basketball game precisely while also being funny. He pulls great material out of his partners. He understands the craft of broadcasting at a cellular level.

“He’s the play-by-play announcer’s play-by-play announcer,” said Fox’s Jason Benetti. “But he’s also the comedic play-by-play announcer’s play-by-play announcer. And he’s the hardworking play-by-play announcer’s play-by-play announcer.”

Of Eagle’s belated ascension to a no. 1 spot, ESPN’s Mike Breen told me, “It was just a matter of time, and everybody in the business knew that. All of us.”

There are precocious announcers who grew up around network television, watching a parent call stepback 3s. See Eagle’s 26-year-old son, Noah, for example. Ian Eagle is different. He’s a child of show business, raised in the wings of a nightclub stage.

To understand how Eagle calls a basketball game, you have to visit him and Jack and Monica in the swinging show-business past. You have to travel to Catskills resorts and $10-a-night hotels on the Las Vegas Strip, where you can hear the sting of the drummer in the house band. That’s where Ian Eagle, the no. 1 announcer, was created.

He was born in Miami. Jack had dragged Monica there for a gig.

Jack had been hired to play the Eden Roc hotel. He was the opening act, the comic appetizer. The headliner was Shirley Bassey, the singer who’d recorded the theme for Goldfinger and would record songs for two more James Bond movies.

On February 9, 1969, Jack opened the 9 p.m. show at the Eden Roc. Then he went to the hospital to meet his newborn son. Then Jack went back to the Eden Roc to open at midnight. Jack was always swooping in and out of Ian’s life.

Jack and Monica were regular performers at Catskills hotels like Grossinger’s and Homowack Lodge. On weekends, they brought Eaggie (as Jack called Ian) from their Queens apartment. When his dad told jokes, Ian would stand in the audience or in the wings or behind the stage, where he could only hear the act and the laughs.

“I was very much in awe,” said Ian, “of how one 5-foot-4, 225-pound man could take over in an instant and within the first minute have the audience eating out of his hands.”

Jack had mischievous eyes that were always gazing down at his waistline. He had a joke about trying to buy a suit (“You’re a toddler 44!” said the haberdasher) and a joke about why men like him made better lovers than slim, sandy-haired handsomes. “When I go to a restaurant and the waiter brings me the menu,” Jack told the audience, “I say: ‘Yes!’” Ba-dum-sssss.

Jack was born in 1926 in Brooklyn. “The uppity comics tell lies,” he said. “They say they’re from Flushing, Long Island.” Jack dropped out of high school, played the trumpet in a band, and then, at the urging of comic Buddy Hackett, began telling jokes himself. He was part of a double act that performed on The Ed Sullivan Show and then went solo. By the 1950s, Jack was playing clubs across the country.

“I remember one time I was backstage,” said Ian. “I locked in on a gentleman that did not laugh, did not crack a smile. I couldn’t stop looking at him the entire show.” Over a postshow milkshake and a toasted bagel with cream cheese, Ian asked about the man.

“I don’t know what’s going on in his life,” said Jack. “Maybe his wife is shtupping his accountant.”

Years later, Eagle told me: “I’m 7. What’s shtupping? But his point was well-taken. I can’t concern myself with every single person. I can only do what I do, and my hope is that it connects with the majority.” He added, “Zero percent of people have a 100 percent approval rating in broadcasting.”

Jack was a classic second-banana comedian. He opened for Bassey in Miami, for Little Anthony and the Imperials at the Copacabana. By his late 40s, he’d watched New York comics like Hackett and Lenny Bruce be headliners in big rooms and become stars.

When Ian was around 9, he rode in the car with his dad after a gig. Ian asked, “Have you thought about changing up your act at all?”

“What?” said Jack.

“Your act. Have you thought about changing up your act?”

“That’s my act,” said Jack. “That works.”

He never changed it.

Jack Eagle called himself “an entity, a semi-name.” For a chunk of his career, Ian could have described himself the same way.

At age 8, Eagle had told his parents he wanted to be a sports announcer. There are few jobs on earth less normal than announcing. But compared to show business, Eagle thought, it was like becoming a CPA.

In 1994, at age 25, Eagle got his first big job calling New Jersey Nets games. In seven seasons, the Nets made the playoffs once. “Using stand-up comedy as an equivalent, you could work your material there and then see what sticks,” said Eagle.

One of Eagle’s partners was Bill Raftery, who is 25 years his senior. Just as Eagle once did an impression of Howard Cosell, he can now do a crackerjack Raf. “He loves to break my … onions,” Raftery told me. Raftery showed Eagle that announcing is a mode of being and that your on-air personality should be a slightly heightened version of your real self.

In 1998, Eagle got his first network gig at CBS, which had just gotten the NFL rights back. While calling Nets games for YES, Eagle climbed the CBS hierarchy, settling behind Nantz as the no. 2 voice for the NFL and college basketball.

From time to time, Eagle was reminded, in the funniest possible way, that he was not yet a headliner. In 2015, CBS assigned newbie announcer Grant Hill to call a Notre Dame–Duke game. When a producer told Hill the name of his play-by-play partner, Hill misheard it as “Iron Eagle.” Iron … eagle … golf, Hill thought. I must be working with Nantz.

That weekend, in Durham, North Carolina, Hill remained unaware that Eagle was his partner even as they watched practice together. “I keep thinking, Who is this production assistant who won’t shut up?” Hill told me. That night, Hill finally realized “Iron” was calling the game.

By 2006, Mike Tirico, Eagle’s college pal from Syracuse, had become a no. 1 announcer at ESPN. In subsequent years, other networks showed interest in Eagle; he took a meeting with Fox. But he found there were no. 1 announcers everywhere. Eagle and Joe Buck were born two months apart.

“He’s never coveted any job—and I bear witness to it,” said Raftery. “He never, ever said, ‘Boy, someday I’d like to …’ He was more in the moment. This is what I’m doing. I’m doing the best I can. And, hopefully, people will notice.”

Eagle credits his decision to stick it out at CBS to watching his father grind away in nightclubs. “I never, ever heard any bitterness,” he said. “I never heard from him, ‘Why them? Why not me?’ I think that mentality stuck with me as well. Worry about you.”

During his second-banana years, Eagle stood out because he was funny. Funny like a comedian rather than like an announcer. “Sometimes, people are mean funny or sarcastic funny,” said Suzanne Smith, a CBS director. “Ian’s always funny funny.”

Eagle is the kind of funnyman who’s always slightly more “on” than you are. If you make a joke, he will improve it. If there’s no joke, Eagle will offer one. Last fall, when I texted him to firm up a lunch date, Eagle wrote back, “Do you like Quiznos?”

TNT’s Reggie Miller calls Eagle “the Michael Scott of broadcasting.” What he means is that Eagle’s delivery is so deadpan that many viewers don’t catch the joke. “If you don’t get it, it’s fine,” said Orioles announcer Kevin Brown, one of Eagle’s many fans in the business. “If you do get it, you feel like you’re part of a special club.”

In 2012, when the Nets made a game-winner in double overtime with Jerry Seinfeld watching from the front row, Eagle exclaimed, “That was real, and that was spectacular!” “Yes, it was!” said his partner, Greg Anthony, missing the reference completely.

Last September, Eagle spoke the Taylor Swift–Travis Kelce romance into existence during a Chiefs-Jaguars game. When Kelce caught a touchdown, Eagle said he’d found a “blank space” in the end zone. “Here’s the best part,” said Charles Davis, his NFL partner. “You never heard another one, did you? He dropped it.”

Like Marv Albert, Eagle looks for comedy outside the edges of the frame. When fans sitting courtside spill their drinks, Eagle and Frank DiGraci, his longtime YES producer, insist that the spillage be shown on camera. “We’ve always been that way,” said DiGraci, “but now there’s extra juice because stuff goes viral.” During Sunday’s UConn-Northwestern NCAA tournament game, you could sense Eagle’s excitement when a ball got stuck between the rim and the backboard. “When there’s a wedgie,” said Noah, “he rises to the wedgie.”

From a Catskills stage, Jack could make everybody in the audience feel like he was speaking directly to them. Eagle tries to get the same effect on TV. “Some might say, ‘You want to feel like you’re listening in on a great conversation,’” he said. “No, no, no, no, no. You want to feel like you’re part of a great conversation.”

Like all good funnymen, Eagle loves to massage the language. Careful viewers of YES will notice that Eagle says the word “ricochet” once during every Nets game. Upon hearing it, DiGraci will say the word into Eagle’s earpiece, just to show he’s paying attention. “Ricochet” is a funny word.

Ian’s mom, Monica Maris, was a child star in Chicago. “I was a professional singer making big money,” Monica once said, “and then had to quit and go to kindergarten.” Ba-dum-sssss.

Monica had big, brown eyes and a smile that hinted she knew something you didn’t. Like her future husband, she dropped out of high school to perform in clubs. A newspaper ad claimed she had the “belting characteristics of Judy Garland.” Monica boasted she could sing 2,000 songs. Her showstopper was “Over the Rainbow.”

“She was born to entertain,” said her friend Susan Griffiths, who performed with her years later. “She was born to sing. She was born to do this.”

Monica was brilliant, said Ian. Every Sunday, he found a completed New York Times crossword puzzle she’d left on the kitchen counter. She taught herself needlepoint and painting, and her creations decorated Ian’s apartments.

In 1967, Monica met Jack at the Playboy Club in Chicago, where she was opening for him. She was 19 years younger than he was. In June, a photographer caught her stepping off a plane in Sydney, Australia, where she and Jack were touring. She wore the highest heels she could find so she would tower over him onstage. We look like the number 10!

Ian talks about his mom differently than he does his dad. Their relationship was more complicated. When Ian was young, Monica struggled with alcoholism. She struggled with anorexia—once, her weight plunged to just over 80 pounds. Ian tries not to look at pictures from that period.

Some mornings, no one in the family’s Queens apartment was allowed to speak to Monica or turn on the lights until she had her coffee. Partly for this reason, Ian has never touched coffee. On those mornings, when Monica finally did speak, she sounded awful.

“How is she going to sing tonight?” Ian would ask his father.

“Eaggie,” Jack would say, “she can go above her chords.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” said Ian.

“She can’t speak to you right now,” said Jack. “She has no voice. But she can sing.”

That night, Ian was back in the wings of a nightclub stage. He watched his mom sing, as if nothing was wrong, only to wilt again afterward.

“The most important thing I learned from her,” said Ian, “was no matter what your physical state is, nobody cares. You are expected to do the job.”

“Years later, when I started broadcasting, it hit me,” he continued. “I’ve got a bunch of games. I didn’t have my A voice. But on the air, I could go above my speaking voice into a different place to be able to project.”

In 1976, when Jack was 50 years old, he finally got the big break in show business he’d been waiting for. He got cast as a monk named Brother Dominic in a commercial for Xerox. In the ad, an abbot asks Brother Dominic to do the exhausting work of copying manuscripts. Wearing his cowl, Brother Dominic goes to a Xerox store and gets copies made. “It’s a miracle,” the abbot says, as Jack’s mischievous eyes look toward the heavens.

The ad ran during the 1977 Super Bowl. In a three-network universe, Jack Eagle became a major entity. “I can be copied but never duplicated,” he quipped. Asked about his dad’s line of work, young Ian was quoted in a newspaper saying, “He’s a monk.” Ba-dum-sssss.

Jack became the go-to comic for TV commercials. He played a bow-tied Mr. Cholesterol in an ad for Fleischmann’s margarine. For Carefree gum, he was Christopher Columbus’s first mate. “He had never seen money like this,” said Ian. Jack moved his family from an apartment in Rego Park to a house in Forest Hills.

Jack and Monica had spent a decade hustling together. Now, Jack had reached a new level. Monica didn’t want to open for him anymore. She wanted to find stardom on her own terms. “She needed to get out,” said Ian. “And she did.”

In their final days performing together, Jack and Monica still ended their act with Monica at stage right and Jack at stage left. “People walked away thinking, What a great couple,” said Ian. “I was 8 years old and thinking, They live in separate bedrooms.” Eagle called the moment when he first saw the artifice of show business “a nice baptism by fire.” In 1978, Monica left the family and began spending parts of the year in Los Angeles. Ian stayed in New York.

From that point on, Ian’s childhood got even stranger. Xerox hired Jack to dress up as Brother Dominic at copy stores and sales meetings across the country. At the height of the monk’s appeal, Jack was on the road for 225 days a year, said Ian. Monica was in Los Angeles, visiting New York less and less.

Ian was nobody’s idea of a latchkey kid. He had the run of a big house. Live-in housekeepers with names like Enid and Elsa made him dinner. What was strange was that Ian began raising himself.

Every night, Ian put himself to bed. He got himself up in the morning. He learned to deal directly with adults. When he started playing Little League Baseball, he called up his friends’ parents to arrange a ride to practice.

“I don’t want to paint a picture like it was difficult,” said Ian. “It wasn’t. It’s just what I knew. I knew it was different.”

“I had zero checks and balances in my life,” he said. In San Francisco, where I met him for lunch before he called the Warriors-Suns season opener, Eagle ordered an orange Fanta. I’d never seen a TV announcer drink a Fanta. When Ian was a kid, his dad issued a rare dictum forbidding soda. Ian persuaded a housekeeper to buy a case of Mountain Dew.

When Jack came back from the road, he had little time for the subtleties of parenting. Once, he took Ian to a new school, P.S. 101 in Queens. The principal looked at Ian’s work and asked if he wanted to skip the third grade.

“You want to be in fourth grade?” Jack asked Ian.

“Yeah, that’s fine,” he said.

He was in the fourth grade.

When Ian was around 11 or 12 years old, he flew by himself to Los Angeles to visit his mom. “She picks me up at the airport,” he told me. “She says, ‘Hey, can’t wait to show you around. We’re going to meet a friend of mine from my acting class.’” The friend was Demi Moore. “I spend the entire day with Demi Moore,” he said.

Another time when he was visiting his mom, Monica flipped him the keys to her Camaro convertible. “You drive,” she said.

“I’ve never driven before,” said Ian.

“Well,” she said, “let’s go.” That’s how he learned to drive.

“I think maybe my senior year of high school was the only time that I ever felt some form of bitterness,” said Ian. His parents were far away when he got into Syracuse to study sportscasting, when he was taking a victory lap. “Even that faded when I realized there was nothing to gain from that,” he said.

“I see a cause and effect from that part of my life to where I eventually ended up,” said Ian. He added: “To be malleable. That’s the word I always come back to in these broadcast setups, these arranged marriages. It’s incumbent upon you to make it work.”

Eagle’s TV partners talk about him like he’s a veteran point guard who welcomed them on their first day of training camp.

“Ian was the first play-by-play guy who really took me under his wing and tried to teach me,” said Turner’s Stan Van Gundy.

“I’m probably not the first person that you’ve talked to that feels like they’re best friends with Ian,” said YES analyst Sarah Kustok. Grant Hill said: “If you can’t get along with Ian Eagle, something’s wrong with you.”

The talent of a no. 1 announcer is often counterbalanced by his constant need to be reminded of it. Eagle talks very little about his career. When he told Noah about getting the no. 1 NCAA job, he buried the news 40 minutes into a phone conversation. As Noah told me: “I’m like, no, that’s not ‘by the way.’ That’s a big deal.”

“You could do research on this story for the next year, and you won’t find somebody that doesn’t love the guy,” said Mike Breen. After complimenting his pal a few more times, Breen joked: “I hope you’re going to balance this story out because everybody is just kissing his ass.”

Breen consulted the Eagle opposition research file, such as it is. “He’s terrible at taking compliments,” said Breen.

When I mentioned this to Eagle, he admitted, “I’m a deflector by nature.”

“I personally think he dyes his hair,” said Breen. “Clearly, I’m very jealous of people whose hair is dark.”

“Not true!” said Eagle.

“He wears too many conservative, navy blue suits,” said Breen.

Maybe. But if your parents had put you in a handsome suit when you were 6 …

Monica Maris lived in Los Angeles for seven years without getting a big break. That came in Las Vegas in 1985. At the Imperial Palace hotel, on the Strip, there was a show of celebrity impersonators called Legends in Concert. Before AI, it was one of the only places you could commune with Elvis Presley or Marilyn Monroe.

At Legends in Concert, the impersonators came onstage one by one: Marilyn, Buddy Holly, then Elvis—Elvis was always last because he was the biggest draw. At the end, they gathered on a stage bathed in smoke and sang the Righteous Brothers’ “Rock and Roll Heaven,” as if waving goodbye from the afterlife.

Monica, who was 40, was cast to play Judy Garland. She played the vampy, raspy-voiced, late-in-life Garland who was decades past The Wizard of Oz. Monica dived into the part. She cut her hair, lost weight, and began stooping to make herself look shorter. Just like Garland, she said, “Well, fine!”

The most important thing I learned from [my mom] was no matter what your physical state is, nobody cares. You are expected to do the job.Ian Eagle

A great celebrity impersonator can make the audience feel like they’ve stumbled into a séance. Monica took the conceit a step further. “Monica really felt that she was communicating with Judy,” said Susan Griffiths, who played Marilyn Monroe in the show. Garland hovered over Monica as a muse and a critic. Monica would come offstage and say, “Well, she didn’t like that performance. My earring flew off!”

In the mid-1980s, the director Ilana Bar-Din began filming Monica and her colleagues for a wonderful documentary called Legends. “I have a little prayer before I go on,” Monica told her of Garland. “I pray to be united with her, in body and soul and spirit and voice. She’s my only friend right now, really, besides my son, who’s too far away from me.”

“Sometimes I think, When is my life going to come back? When can I live again?” said Monica. “Because everything is tied up now with Judy.” She spoke to Garland: “I’ve been so selfish about giving you life, haven’t I?”

When Ian was a senior in high school, he sat in the auditorium at the Imperial Palace, as he had in clubs in the Catskills, watching his mom sing “Over the Rainbow.” Eagle told me, “I was like, Oh, shit. She’s not doing Monica Maris anymore. That’s done. She’s doing Judy Garland.”

Monica’s commitment to her breakout role was complete. When she bought a house in Las Vegas, she interviewed Garland’s former husband so she could decorate it in the star’s preferred style. Monica hung a portrait of her muse above her bed. The license plate on her Camaro said “GARLAND.”

“There was a 15-year age difference between us,” said Griffiths. “I always looked at Monica as an adult. But in other ways, I looked at her as a child.” In Las Vegas, Monica was happy that she was sober, happy that she had finally gotten her own break in show business apart from Jack. “The fact that she could go on without him and create this whole world for herself was a big accomplishment for her,” said Griffiths.

“I got to see her at that stage of her life doing very well in her career,” said Ian. “And I think it was important for her that I saw it.”

Eagle hardly has a memory of his mom in which she isn’t smoking a cigarette. In 1988, Monica was diagnosed with lung cancer. Using her old show-business ethic, she performed in Legends in Concert night after night until she collapsed in the arms of the producer and said, “I’m done.”

Monica never mentioned her illness to Ian. In November 1988, when Ian was at Syracuse, he got a call from a man he had never met. The man, who said he was Monica’s fiancé, told Ian his mom was in the hospital and that he needed to get there immediately.

Ian flew to Las Vegas and arrived at the hospital after midnight. “She was a shell of the person that I knew,” he said. “I took her hand, spoke with her. She could not speak. She squeezed my hand. She had a tear roll down one eye, as cliché as it sounds. I fell asleep on the hospital room floor, and at 2:15 she died.”

Maris is interred at a mausoleum near the Las Vegas airport. The inscription on her crypt reads “Over the Rainbow.”

When Ian was a kid, he followed Jack to work. When Noah was the same age, he began tagging along with Ian. They weren’t going to a Catskills nightclub. They were going to the TV booth at Giants Stadium. Ian had ditched the handsome suit for a network blazer. Ian called it “a re-creation of my setup—Dad holding the mic and him noticing every movement, every gesture.”

Noah, who now holds a mic for NBC, was struck by how Ian took command of that small room. Right before he went on air, Ian would crack a joke or sing along with a song on the stadium PA. Noah could see Ian’s partner loosen up, and then watch that looseness travel all the way down to the truck so that, in an instant, everyone on the crew was happy. “He always said he never felt like he’d be as funny as his dad,” said Noah Eagle. “I feel the same about mine.”