When MLB came back from winter break a year ago, the game had undergone a makeover. The pitch clock came in; extreme infield shifts went out; the running game got off the mat. This year, the uniforms are different (derogatory), but the sport is largely the same. The tweaks on display on Opening Day were virtually invisible: Two seconds were cut from the pitch clock with runners on base. The runner’s lane to first base was widened, and umpires were instructed to crack down on violations of a rarely enforced obstruction rule around the bases. Each team’s complement of mound visits was trimmed from five to (gasp) four. On the rules front, this season’s stability seems like a lull between the upheaval of last year and the next inevitable affront to purists, the automated strike zone, which could be coming in some form to a big league ballpark near you as soon as 2025.

Behind the scenes, though, MLB is gearing up to take on a challenge more daunting than any it tackled last year. In 2023, the league addressed its pace problem. Now it’s trying to address its ace problem.

The latest edition of The Athletic’s annual ace ranking reported only one unanimous selection among the executives, scouts, and analysts surveyed: the Yankees’ Gerrit Cole. Cole, the American League’s reigning Cy Young winner, was out with an elbow injury—diagnosed as nerve inflammation and edema—by the time that piece was published. Athletic senior writer Andy McCullough, who’s been assessing the state of acedom each spring since 2014, has never seen such slim pickings. “Pitchers are better than ever, but they are breaking at a worrisome rate, at a time when teams are asking less of starters than ever before,” McCullough says. “That instability leads to fluctuation among aces, because perhaps the most important quality among a no. 1 is reliability.”

This year’s group of Opening Day starters featured 15 first-timers, the third-highest total of the 30-team era. (The average is 11.) Injuries were largely to blame: Six of last year’s Opening Day starters—Cole, Shohei Ohtani, Sandy Alcantara, Jacob deGrom, Shane McClanahan, and Germán Márquez—suffered elbow breakdowns that prevented them from reprising their performances, and two others (Eduardo Rodriguez and Max Scherzer) were out with other ailments. The list of starters who might’ve drawn Opening Day assignments had they not been slowed or sidelined by physical complaints included Lucas Giolito, Sonny Gray, Justin Verlander, Kodai Senga, Brandon Woodruff, and Kevin Gausman. Of the nine qualified starters with the lowest ERAs last season, only one, Justin Steele, was in action on Opening Day—and naturally, he got hurt. “Of the first 10 pitchers you can name, seven aren’t pitching right now due to injury,” Baseball Prospectus cofounder Joe Sheehan wrote in his newsletter last Thursday, with just the tip of his tongue in cheek.

There are plenty of off-the-field issues facing baseball—some unique to the sport and others (the cable bubble’s burst, sports-betting scandals, etc.) more universal. On the field, though, there’s no bigger bugaboo than the one that keeps players off it: pitcher injuries. That perennial problem, which haunts starters, swingmen, setup men, and firemen alike, has intensified to the point that MLB is buckling down to do something about it—or, at least, to try to decide what to do about it.

According to an MLB source, the league is conducting a comprehensive study of pitcher injuries. This ongoing deep dive, which began last October, has consisted of data analysis and approximately 100 interviews with informed figures, including doctors, trainers, independent researchers, college coaches, amateur baseball coaches and stakeholders, former pitchers, front-office members, pitching coaches, and current players. The study’s end date is still underdetermined; for now, the league is following leads as they develop, and each conversation tends to spark a few more. When the study does conclude, though—possibly later this year—the league intends to form a task force that will make recommendations for protecting pitchers and, in the process, restoring some of the starter’s lost luster.

Dr. Glenn Fleisig, biomechanics research director at the American Sports Medicine Institute and injury research adviser for MLB, is one of the experts the league has consulted. “It’s not just a survey to study the situation,” he says. “It’s trying to study the situation and come up with some solutions and implement some solutions.” In that sense, he deems it “very parallel” to the process the league followed in diagnosing and treating the game’s symptoms from an entertainment standpoint. The goal this time is to “copy that model … and do it now from a safety point of view.” Fleisig previously served on the advisory committee that helped formulate MLB and USA Baseball’s 2014 Pitch Smart guidelines for preventing overuse injuries in youth pitchers. This new initiative, he says, is “the most organized, concentrated effort since then.”

It will have to be. For all the false starts on the path to the pitch clock, the eventual solution had existed in something resembling its final form for 60-plus years. And once the exceedingly simple fix was in place, the payoff was immediate. The remedy for the problem that plagues pitchers probably won’t be as, um, surgical. “It’s really hard to solve!” says ESPN senior baseball insider Jeff Passan, author of The Arm, a 2016 book about pitcher injuries. “There would need to be massive change starting at the lowest of youth levels, and I fear it would take perhaps half a generation before we saw palpable results. Are we patient enough as a sport—as a society—for that? I have my doubts.”

So does the anonymous professional pitcher who in February opined in a piece for Baseball Prospectus that “the answer is simple, there isn’t one.” MLB believes there could be. But to implement it won’t just require overcoming inertia, skepticism, and fealty to tradition. It will require transcending the limitations of human psychology and physiology, too.

Anatomically speaking, the elbow is the bane of baseball. Its ulnar collateral ligament—three stabilizing bands of tissue on the inside of the elbow that connect the humerus (the upper-arm bone) to the ulna (a long bone in the forearm)—is the weak point (and all too often, the breaking point) in the kinetic chain that produces a pitch. The UCL can’t be significantly strengthened through exercise and is subjected to such extreme strain during the delivery that with enough repetition, it’s almost bound to tear. The original sports surgeons most associated with UCL replacements have themselves been replaced (Keith Meister and Neal ElAttrache are the most prominent successors to the recently retired James Andrews and the late Frank Jobe, the latter of whom pioneered the procedure), but the elbow reassembly line has only accelerated. The fact that so many fans know the names of these surgeons—and dread their invocation—is itself a sign of how pervasive the UCL scourge is.

UCL replacement surgery, colloquially called Tommy John surgery, was first performed on the eponymous guinea pitcher, who gave it that nickname in September 1974. More than three years elapsed between the first and second (and also between the second and third) procedures performed on major leaguers, which seems incredibly quaint considering that last year, roughly two TJ surgeries per week were performed on major or minor leaguers between the beginning of spring training and the end of the World Series. The peak (to this point) period for UCL replacements was 2021, when pitchers’ arms suffered from pandemic-induced disruptions to their routines following the shortened (or, in the minor leagues’ case, canceled) 2020 season. But the long-term trend is a steady climb, and the totals in each of the past two seasons have easily surpassed pre-pandemic levels.

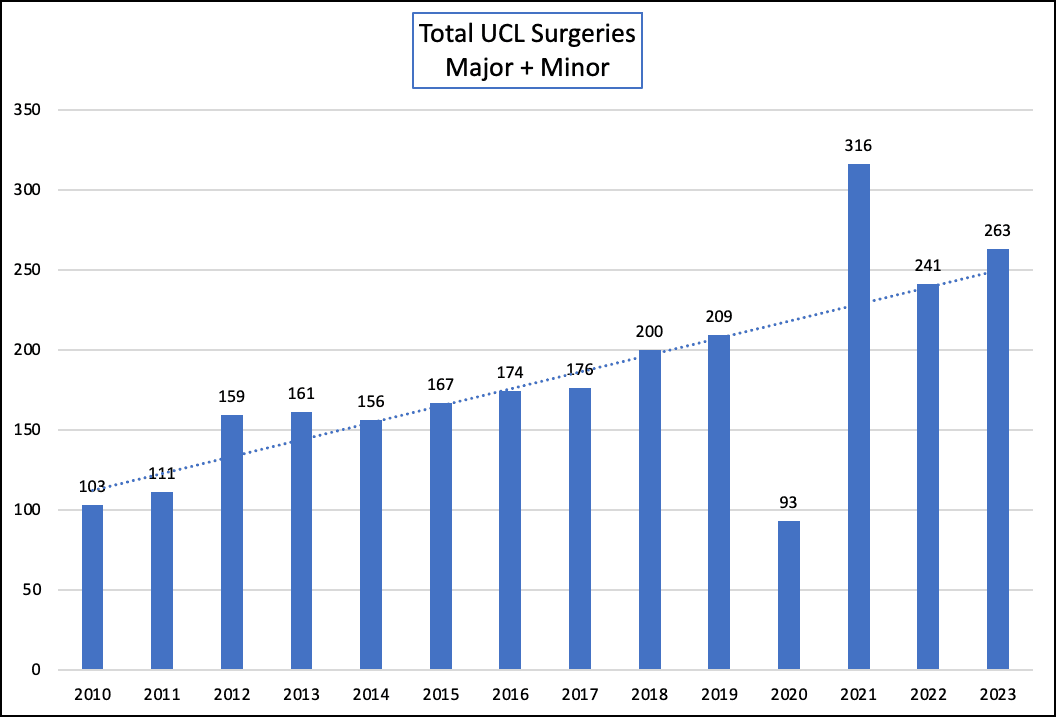

Stan Conte, who’s worked as a head athletic trainer or director of medical services for three MLB teams and founded the Conte Performance facility in Scottsdale, provided a graph of the number of UCL surgeries performed on major leaguers or minor leaguers each year since 2010:

Last year’s total of 263 surgeries is more than twice the tally from 2011. It’s almost 70 percent higher than the count from 2014, when Andrews pronounced Tommy John surgeries “an epidemic.” The continued uptick is particularly concerning in light of MLB’s 2021 contraction of the minor leagues, which removed a quarter of the 160 existing affiliated teams—and, by extension, hundreds of pitchers who would’ve been potential surgery recipients.

According to independent Tommy John surgery researcher Jon Roegele, 35.6 percent of MLB’s non-position-player pitchers in 2023 wore a telltale Tommy John surgery scar on their throwing arm, almost 10 percentage points higher than the figure from 2017. Per Roegele, 15 pitchers underwent Tommy John surgery or a newer approach to repairing the UCL, internal brace repair, in March 2024, and many more—including Cole, Kyle Bradish, Eury Pérez, José Urquidy, Jordan Romano, Matt Brash, Bryan Woo, and Luis Patiño—are in elbow limbo, hoping their joints won’t protest when they return to full effort after taking time off for inflammation and discomfort to subside. This time of year is always the worst for elbow and shoulder injuries, as pitchers push too hard ramping up for the season or realize that rest didn’t cure a problem that was bothering them last season. So it’s not surprising that this spring has exacted such a heavy toll. That lack of surprise also signals a sorry state of affairs; it’s bad that we’re accustomed to an annual demolishment of depth.

Of the 166 players on Opening Day injured lists, 132 (79.5 percent) were pitchers. Amid all those injury-related absences, forecasting teams’ pitching performance is sometimes almost as much about projecting players who are out as players who are active. A few contending teams—the Rangers (Scherzer, deGrom, Tyler Mahle), Rays (Shane Baz, Drew Rasmussen, Jeffrey Springs), Dodgers (Walker Buehler, Clayton Kershaw, Dustin May), and Astros (Luis Garcia, Lance McCullers Jr.)—entered this season with provisional rotations that they hope will be bolstered midseason by multiple surgically repaired pitchers. Other contenders whose staffs seem strong today may soon suffer just as many midseason losses.

This constant culling of the herd turns the MLB season into a game of UCL roulette. Injuries have always played a part in dictating the course of sports, but given the frequency of serious pitching injuries and the compression of this season’s projected standings, it’s easier than ever to picture scenarios in which victory comes down to whose elbow goes sproing and whose stays intact (at least temporarily). More frustrating and worrisome still, there’s seemingly little teams and players can do to mitigate the risk—and, relatedly, little anyone can do to predict disaster. It’s high time for a task force.

The best predictor of future injury is past injury, so no one was shocked when deGrom’s ligament gave out after his many previous trips to the injured list. But Cole and Giolito—the latter of whom underwent an internal brace repair in mid-March—were second and tied for fifth, respectively, in major league games started from 2018 through 2023. Giolito had Tommy John surgery shortly after being drafted 16th overall in 2012, but he hadn’t had an arm injury since making the majors in 2016. The Sox signed him partly due to that dependability: Although the quality of his performance had varied over the past several seasons, his ability to take the ball had not. “At the very least he should provide some much-needed durability,” The Athletic’s Chad Jennings wrote in response to the signing.

But particularly with pitchers—who “get hurt more frequently and stay on the IL longer than batters,” per Baseball Prospectus—the “very least” is always zero. If a pitcher has been hurt before, the knock on him goes: He can’t stay healthy. If a pitcher has been healthy enough to pitch prolifically, though, that’s also concerning: Lots of mileage on that arm. Anxiety-wise, you can’t win either way. And because elbow injuries often strike without warning, a fan can’t be confident that a pitcher’s health will hold up beyond the next pitch. Last year, non-position-player pitchers accounted for 55 percent of major leaguers—more than half the players, and much more than half the player pool’s precarity. Every pitcher’s season (and by extension, every team’s) is hanging by a thread—or, maybe more accurately, by a thin collection of collagen fibers surrounded by a mesh of loose connective tissue. (In case you were wondering what ligaments are made of.) It all feels too fragile for comfort.

Might UCLs be skewing our sense of the situation? Tommy John surgery counts have increased, but that’s only part of the picture. Perceptions of pitcher injury rates might be a bit like perceptions of crime rates. (Bear with me.) It’s almost always the case that the majority of Americans think crime rates are getting worse in the U.S., even when they’re improving. That’s partly because crime is covered in a way that preys on humans’ inherent negativity bias. “If it bleeds, it leads” probably applies to pitchers, too. Could the panic about pitchers be partly based on vibes?

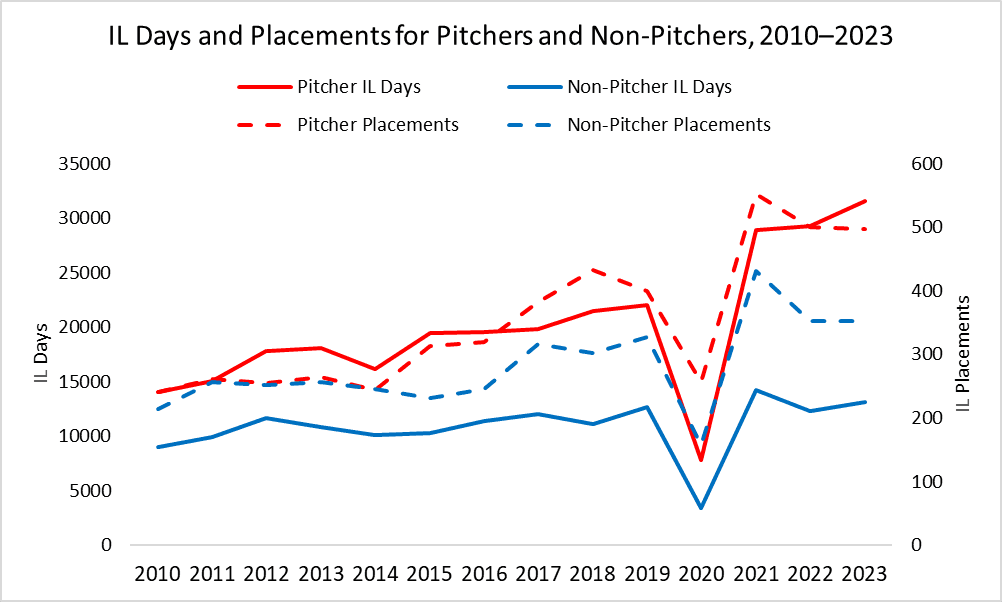

Probably not. According to data shared by MLB, the number of days pitchers spent on the IL last season (31,558) more than doubled the annual average from 2000-04 (15,178). The number of IL placements has more than doubled, too. Moreover, the baseball butcher’s bills for pitchers and non-pitchers have diverged dramatically, especially after the pandemic. From 2011 to 2013, pitcher IL placements outstripped non-pitcher placements by only 2 percent. That differential rose to 36 percent from 2021 to 2023. And the gap in IL days soared from 58 percent higher for pitchers than for non-pitchers to 127 percent higher.

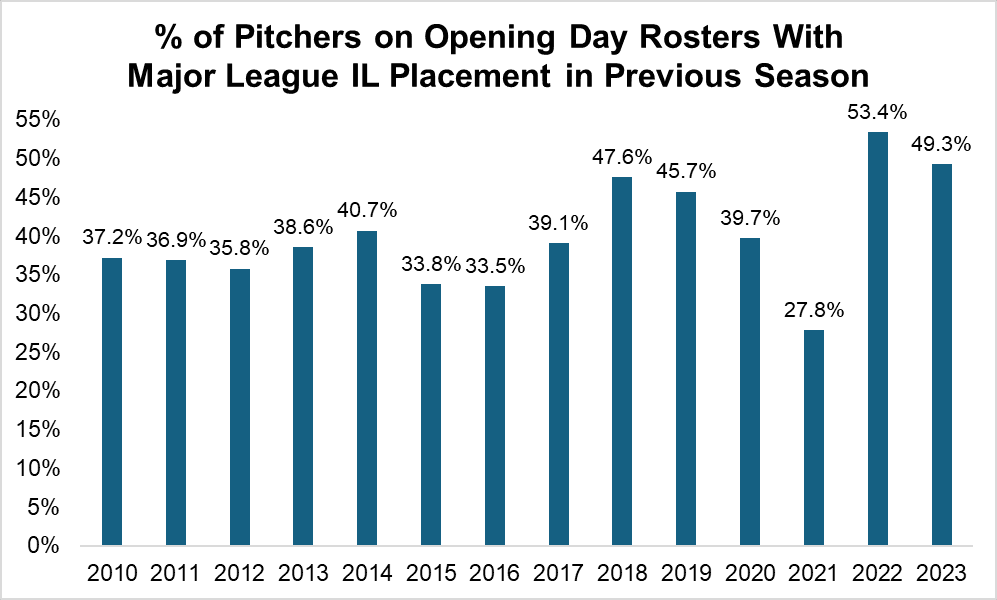

As noted above, past injuries are the best predictors of future injuries, so as more pitchers get hurt, the problem compounds. It doesn’t bode well that roughly half of the pitchers on Opening Day rosters in the past two seasons had been on the IL the year prior.

Granted, IL use isn’t a perfect proxy for injury rates. The “problem with the IL is that it is not an injury database,” Conte says. “It is a roster management tool, so [it’s] difficult to use the IL as injury data.” The minimum IL stay for pitchers has fluctuated between 10 and 15 days, and teams’ willingness to put players on the shelf has also shifted over time. Although the number of innings it takes for a team to get through the regular season hasn’t changed, the number of pitchers it uses to do so has skyrocketed. Teams now stream starters and relievers like overactive fantasy owners, rotating tired arms out and fresh arms in on shuttles to and from Triple-A. Maybe more arms mean more injuries.

Ideally, then, we would compare pitcher durability across eras in a way that wouldn’t be distorted by changes in IL utilization or pitching staff construction. Last year, one such study surfaced, authored by Bill James.

James, a habitual contrarian who, true to form, denies that he’s a contrarian, has historically been skeptical that pitcher injury rates have really risen. Sic semper erat, et sic semper erit, James seemed to be saying: Thus has it always been, and thus shall it ever be. Pitching has always been hazardous to health, and pitchers have always taken the risk that their careers will be cut short; at least now there are reliable remedies for problems that once would’ve been automatic career enders.

But last September, in a study published on his website, James changed his mind. Reasoning that injuries are the main impediment to pitchers’ ability to retain their value over time, James classified every pitcher season since the start of the 20th century on a 10-point scale, relative to their contemporaries, then determined how well the Level 10 pitchers, Level 9 pitchers, Level 8 pitchers, and so on held their value long-term. Using that method, he could assess how the best pitchers of, say, the 1910s compared to the best pitchers of the 2010s. The news was not good.

“The belief that the number of pitcher injuries is increasing seems to be clearly true,” James concluded. “The rates of pitcher value retention have decreased steadily in recent decades, and have declined sharply in the last few years. This is fully consistent with the widespread belief that pitcher injuries are increasing.” The percentage of initial value retained over periods of five or 10 years is dropping, James wrote, “because not as many pitchers are having full careers. I don’t really think there is any other explanation for it. … Careers really are getting shorter, not only in terms of innings but in terms of years. Fewer top-level pitchers are able to stay at the top; fewer mid-level pitchers are able to stay in the middle.”

In earlier eras, pitchers racked up what we would consider backbreaking workloads, and it wasn’t uncommon to treat sore arms by extracting teeth. (A prescription that persisted into the 1970s, in at least one case.) Yet today’s far lighter workloads are still figuratively (and sometimes literally) backbreaking. Apparently the pitchers of today—used sparingly, evaluated noninvasively via imaging technology that used to exist only in Dr. McCoy’s medical bay, and, if necessary, rebuilt like Colonel Steve Austin—are less likely to last than their predecessors were when baseball’s foremost medical practitioner went by “Bonesetter” Reese. Why? And what, if anything, can be done about it?

If I had to nominate one player as a microcosm of the modern major league pitcher, it might be 25-year-old right-handed Mariners reliever Matt Brash. Brash, who ranked fourth in FanGraphs WAR among relief-only arms last season, throws a 98 mph fastball and an 89 mph slider. He rarely subtracts from those speeds. “I throw my stuff full effort,” Brash said two years ago. “I don’t take a pitch off, I don’t baby anything, I’m throwing it as hard as I can every pitch.” The only time he dips below max effort is when he’s working his way back from an injury—as he is now, having recently lost time to elbow inflammation, which some fear may be a prelude to a more serious problem.

As Seattle Times Mariners beat writer Ryan Divish told me last month, “It’s not a matter of if, with Matt Brash, it’s just a matter of when. … Given how he throws, the violence with which he throws, the max effort, the mechanics, and the pitch selection, it’s a matter of time. But if they can get a season out of him, then that’s pretty big.” The Mariners know there’s a minefield ahead; they’re just trying to tiptoe through it.

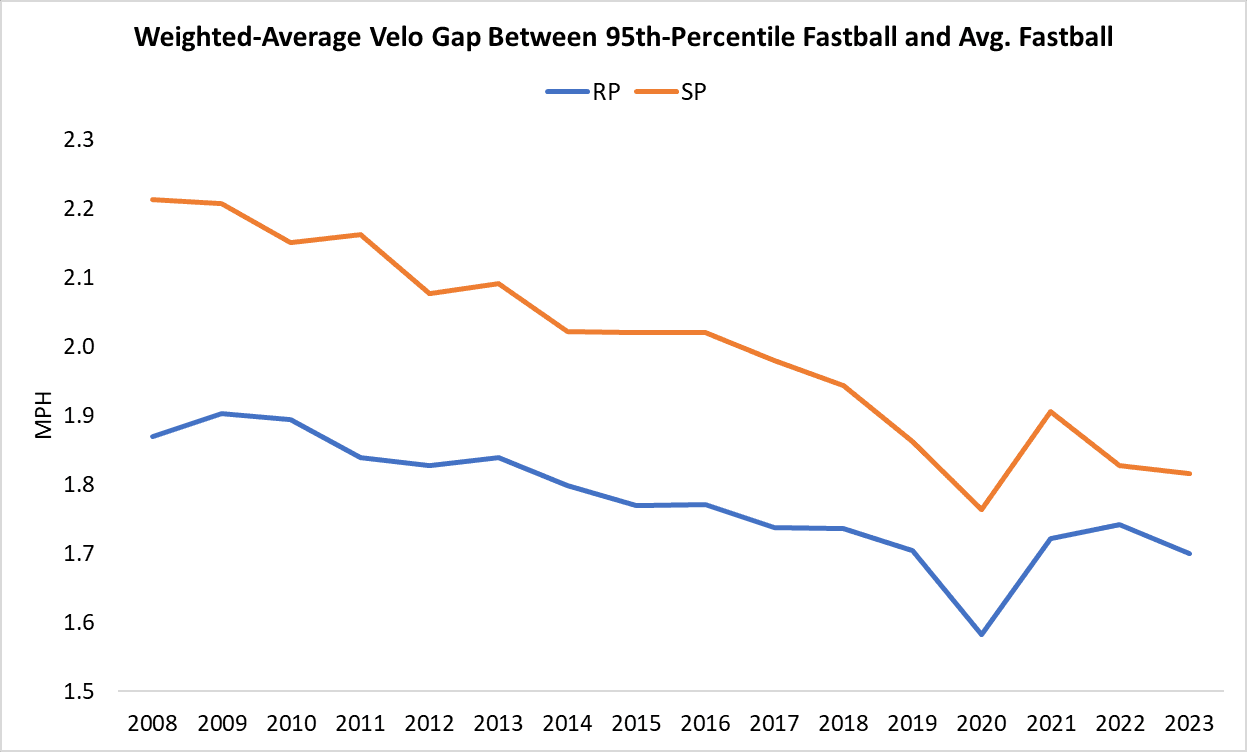

So is every other team, to some extent, because the league looks more Brash by the year. The chart below shows the average annual difference, weighted by workload, between relievers’ and starters’ average four-seam fastball speed and 95th-percentile fastball speed (as in, the value that would be faster than all but 5 percent of a pitcher’s other fastballs). In other words, this is the speed difference between where pitchers’ fastballs “sit” and where they can dial them up to when they’re throwing max effort. The smaller the difference, the closer their speeds are sitting toward the top end of their range.

Aside from a one-year blip during 2020’s 60-game schedule—when, perhaps, pitchers really aired it out, knowing they didn’t need to save their strength for a long season—the gap has decreased by a small amount almost every year. This chart, like an accompanying one on the gap between pitchers’ fast and slow four-seamers, covers only the pitch-tracking era, which began in 2008, but even over that 15-year span, MLB has clearly become more of a max-effort league.

This shift from pitching in a pinch to letting it eat isn’t the only suspect in the case of the missing pitchers, but of all the possible culprits, max-effort pitching takes up the most space on the evidence board. Pitch velocity and elbow and shoulder torque are only weakly correlated across pitchers because each delivery is different: In terms of strain imposed on the arm, one pitcher’s 93 mph might be akin to another’s 96. But within the same pitcher’s deliveries, the relationship is strong. In the words of one Driveline Baseball literature review, “As one pitcher throws harder, he’ll experience more stress.”

The anonymous pro pitcher (and Tommy John surgery recipient) who wrote a guest piece for BP asserted, “The reason that pitchers get hurt so often is simple: The human body is not meant to do what pitchers do.” That’s true, to an extent—pitchers are always going to get hurt, barring bionic arm implants. (Which really might be barred someday.) But if pitchers are getting hurt more often than they used to, it’s not because human anatomy has changed. It’s because pitching has. And much as it did with game times, defensive alignments, and stolen-base rates, MLB wants to change it back.

Fleisig says there are three main injury risk factors for pitchers: effort (which manifests as velocity), volume of pitching, and mechanics. All are interrelated, but pitch counts and innings totals can’t be the problem for pros because those have plummeted in both the majors and the minors. (“You see guys nowadays get called up who’ve never thrown five innings in their life,” Cubs pitcher Jameson Taillon marveled in February.) Maybe mechanics have become too homogeneous, less natural, or too high stress, but if so, that’s probably a by-product of the game’s near-universal preference for speed. “People are trying to pitch as hard as possible, as fast as possible, is the new factor,” Fleisig says, adding that of the three risk factors, “velocity is now the number one.”

Downsizing one value (volume) in the injury equation seems to have hurt pitchers, if anything: Counterintuitively, pitching less is still bad for you if it means pitching harder. Lower workloads with higher injury rates is the worst of both worlds.

Last season, there were 68 pitchers who worked exclusively as a starter, made more than 10 starts, and recorded a better-than-average park-adjusted FIP. The Marlins employed the one with the highest average innings pitched per start (Alcantara, 6.6) and the one with the lowest (Pérez, 4.8). Both got hurt: Alcantara had Tommy John surgery in October, and Pérez is trying to escape the same fate as he nurses his elbow inflammation. Alcantara is a 28-year-old throwback who pitched deep into games, whereas the 20-year-old Pérez has been used extremely lightly. What do they have in common? Well, quite a lot. But most relevant to our purpose, they ranked third and fourth, respectively, in average fastball velocity among starters last season with at least 50 innings pitched.

So why throw so hard? All else being equal, faster pitches are harder to hit. Pitchers know this—and know that the people who pay them know this—so they keep going, and throwing, all out. Teams know this, so they keep acquiring pitchers who throw hard and trying to make the pitchers they have throw harder. They also pull starters earlier in games—largely to avoid the times-through-the-order penalty, but partly so that their pitchers won’t have to suppress the all-important “stuff” they’re graded on internally and publicly (and that they try to enhance at sometimes taxing pitch-design sessions between outings). Instead, the starters can pitch like relievers, emptying the tank early on because they’re confident that they won’t be asked to shoulder a late load.

Essentially, MLB pitchers are too good for their own good. And they know it. As one anonymous pitching coach recently told The Athletic, “Analytics says velo is super important. Pitchers and analysts pursue velo. The pitchers that don’t do this retire. The ones that stay take on some injury risk to avoid working at Costco.”

It’s possible that the Peltzman effect explains some of pitchers’ risk-taking: Because Tommy John surgery usually isn’t career ending, pitchers may be more willing to push the boundaries of their bodies than they would be if there were no second chances at a pristine UCL. We can understand these rational calculations without also liking or living with them. “I get that the relationship between velocity and effectiveness is generally causative, and to suggest otherwise would be extreme Luddite behavior,” Passan says. “But likewise I understand that velo chasing comes at multiple costs that I believe make the game demonstrably worse: shorter starts and higher injury rates. This is modern baseball’s Faustian bargain.”

Pitchers don’t deny that they’re making a deal with the devil of velocity. BP’s anonymous pitcher wrote, “I think I speak for the dominant portion of pitchers when I say that most of us will take the higher injury risk associated with throwing harder in exchange for a better chance of getting hitters out. … The goal of pitching isn’t to avoid injury, but to avoid losing.”

That’s true too, but it’s also a short-term view—which is understandable, given that between the injuries and the constant roster reshuffling, most major league careers don’t last long these days. Players and teams are trying to win games and make money. Unless the good of the sport and the spectators happens to align with those goals, players and teams aren’t incentivized to care. According to the pitcher, nobody is: “No one will be doing anything to cure the epidemic, because it isn’t in anyone’s best interest to do so.”

Enter the entity with the “best interests of baseball” clause.

Fleisig says, “I hear people say things like, ‘Major League Baseball, they don’t have any interest in preventing injuries, they just have the next-man-up mentality.’ … I strongly disagree with that. … That may be the philosophy at some teams, but at the league level, I can strongly tell you that is not the desire. … The league definitely wants to reduce the risk of injuries.”

Granted, spreading out innings among more pitchers probably depresses payrolls, and the owners who stand to save as a result are commissioner Rob Manfred’s bosses. But breakable, fungible pitchers make the sport less fun to follow in a few ways.

Maybe the most pernicious aspect of pitcher fragility is its tendency to make us feel ambivalent about excellence instead of celebrating it. Statcast and its omnipresent percentile scores have amplified fans’ tendency to fixate on tools: We sit up and pay attention when the numbers and the eye test say a hitter sprints super fast or swings super hard. When a pitcher throws super hard, though, the excitement is tempered and served with a side of dread.

In March, Ohtani’s surgeon, Dr. ElAttrache, recalled a 103.5 mph pitch Ohtani supposedly threw during last year’s spring training. “Everybody was ecstatic,” ElAttrache said. “I was maybe the only one concerned.” To the internet’s knowledge, Ohtani hasn’t thrown a pitch quite that hard—might ElAttrache have been remembering Ohtani’s 102 mph heat in the World Baseball Classic?—but even if he had, the surgeon wouldn’t have been the only one worried. This spring, A’s prospect Mason Miller embraced a new bullpen role designed to make him more available than he was during his rookie campaign, when he missed four months after suffering a UCL sprain. When I read that Miller had touched 103 on March 1, I didn’t rejoice at the prospect of seeing him top triple digits for years to come. I cringed in anticipation of a trip to the OR, just as I used to when deGrom threw harder than anyone (and harder than he had to).

Thanks to injuries and voluntarily reduced workloads, the best minor league pitchers don’t appear on prospect lists as prominently as they used to. The best big league pitchers don’t amass as much FanGraphs WAR. And they don’t serve as readily as the sport’s protagonists, whether over a season or in a single game. “Historically, starting pitchers have been some of the biggest stars in the game, and the way that pitching is being used right now has caused a diminution of the star quality for some of our starters,” Manfred said before the first game of last year’s World Series. He added, “I think that there’s a lot of fans who feel like the change from ‘Let’s see what today’s pitching matchup is’ to ‘Who’s the opener today?’ has not been positive.”

The commissioner’s causes and mandates often aren’t to my liking—now that the pitch clock has dramatically reduced game lengths, can the concept of the zombie runner be impaled on something pointy?—but I’m with Manfred on this one. (Or maybe he’s with me.) We might be in lockstep on something else, too: what to do about it.

My stance on the panacea for pitching—or the closest we can come to one—hasn’t changed since I made the case two years ago: Active roster limits on pitchers have to go lower. “I don’t think it’s had the desired effect,” Manfred said last fall of the current 13-pitcher limit, which went into effect (to teams’ chagrin) in June 2022. “There are a few numbers smaller than 13.”

If max-effort pitching is the primary cause of the pileup of pitcher injuries, then limiting teams to fewer pitchers at any particular time—and tightening roster rules to prevent teams from frequently reshuffling the 12 (or, eventually, 11 or 10) arms available to them—would strongly discourage the undesirable behavior. Without the backstop of virtually bottomless bullpens, starters would be forced to pace themselves, as they used to when they were expected to “finish what they started.” They would once again have to take a little off their typical pitch and pick their spots to “reach back for a little extra.” They would push their personal velocities into the red less often and accumulate less strain on their arms.

That restriction would have a number of nice knock-on effects: starters who’d go deeper into games; lower strikeout rates, higher batting averages, and more base runners; fewer pitching changes; less Blake Snell–style nibbling to induce chases and fewer pitches per plate appearance; more comebacks; more players who reach increasingly elusive old-school statistical milestones. It would also replace push-button bullpen moves and inject some serious strategy as managers weigh their desire for a fresh pitcher against concerns about being shorthanded or rapidly inflating season-long workloads.

There are any number of heavy-handed inducements or punishments MLB could add to the books to try to protect teams and players from their own competitive impulses. The league could dramatically expand the three-batter-minimum rule. It could legislate the maximum number of pitchers permissible in a game. It could institute the double-hook DH. (Eh.) It could impose a minimum start length, unless a certain number of runs is allowed. But no other measure would so elegantly address several complaints about baseball, so unobtrusively.

In February, Scherzer said, “We need to incentivize keeping the starter in the game longer. We’re going to have to come up with rules to do this. It’s not going to self-correct.” Less helpfully, he called the 12-pitcher limit “a terrible idea.” Perhaps pitchers can’t be counted on to reduce their own ranks in favor of position players. Installing a NASCAR-style restrictor plate for pitching may be Manfred’s job.

For now, his job is to listen, learn, and weigh the evidence without prejudging. Not everyone agrees that velo is the only villain. Pitch speeds have increased by several miles per hour since the early 2000s, but breaking ball percentages have risen just as starkly. Some observers single out spin and sweepers for blame, though Fleisig has found that curveballs and sliders are no more stressful than fastballs. (They may be more stressful on a per-mph basis.) Jim Creighton, the mid-19th-century hurler who’s credited with pioneering the fastball, could have testified to that: The torque it took to throw his heat may have killed him. And ol’ Bonesetter Reese prefigured Fleisig when he wrote, “It’s not the curve ball pitchers who come the more often … but the boys who try to throw the ball past a batter, the speed ball pitchers. … If the soreness is in the elbow it’s a speed ball pitcher nine times out of 10.”

Some people point to the pitch clock as a contributing factor, citing its presumed part in fostering fatigue. In light of the clock’s success and high approval ratings, MLB is highly motivated to defend the measure’s injury record. The league cites an independent, unpublished Johns Hopkins University study that it says saw no link between between accelerated pace and increased injury rate, and both Baseball Prospectus and FanGraphs have published their own research that failed to find a clear connection. Although it will take more than one season to rule out a relationship, injury rates started rising at a time when the pauses between pitches were getting longer. It’s pretty apparent that the problem predated the clock.

It’s also apparent that the problem predates pitchers’ debuts in the big leagues, or even in the pros. Pitch counts and innings totals are down in the minors and majors, but that doesn’t mean amateurs aren’t being overworked as they specialize early and chase radar readings at scout-filled showcase events. “The guy who’s playing in a high school, and he’s on his high school team, and his travel team, and a showcase, or the international player who’s playing year-round in some tropical-weather place … those are the people who are showing up in professional baseball with the damage already in their arms,” Fleisig says. MLB notes that from 2011 to 2013, six pitchers drafted in the top 10 rounds had histories of UCL reconstruction. From 2021 to 2023, 24 did.

Fleisig says Pitch Smart bent the curve (if not the curveball) and that the pitch counts imposed from Little League through college temporarily lowered the rate of the uptick in injuries. Lately, the slope has grown steeper. “Let’s study the situation,” he says. “Let’s brainstorm about some solutions. Let’s try it both in the lab research and also field research, and then move forward. … I am optimistic that this is going to happen and work.” The pace problem struck some as intractable, too, until suddenly it didn’t.

As The Arm turns eight this week, I ask Passan a version of the question Ronald Reagan once posed to Jimmy Carter: Are elbows better off than they were eight years ago?

Although he’s heartened that internal brace repairs (which he previewed in the book) have halved the recovery time from Tommy John surgery for eligible pitchers, he points out that improving repairs “doesn’t get to the heart of the issue, which is that something is causing elbows to break. The institution of baseball has refused to address what I believe to be the root cause: a system whose fealty to performance does not deeply enough weigh the consequences of its cost. … So on, I fear, we go, with this dirty little not-really-a-secret underpinning the game’s entire pitching infrastructure: As long as scouts, evaluators, and analysts continue to emphasize velocity as the ultimate indicator of future success, that sentiment will filter down to lower levels and guide pitching development to the same broken place.”

For pitchers’ arms, and baseball, to be less broken, the increase in injuries had to be classified as the crisis it is. That necessary step, however insufficient, is being taken now. “Injuries to pitchers are increasing,” James’s study concluded. “That’s a problem. There is a solution. Maybe you know what it is.” If you do, MLB might like to talk to you.

Thanks to Lucas Apostoleris and Ryan Nelson for research assistance.