“At my age, I can afford for film to be a passion and not a business.” That’s what Francis Ford Coppola told me 15 years ago during an interview about his 2009 film, Tetro, a glossy, quasi-autobiographical melodrama starring Alden Ehrenreich and Vincent Gallo that he described as being part of a professional rebirth—a “second career” whose guiding mandate (made possible by the Oscar winner’s long-fermenting sideline as a celebrity vintner) was to stay outside the studio system that made him both an icon and a punchline in the second half of the 20th century. More than any other member of his easy-riding cohort, Coppola emerged at the beginning of the ’70s as the face of the New Hollywood—a status beholden to the industry-shaking success of The Godfather films, and one that he retains, proudly but a bit ruefully, because of the startling unevenness of his post–Apocalypse Now output.

The idea that Coppola lost his mojo in the ’80s has always been a middlebrow myth, albeit one tied to a very real capacity for hubris; when he made a biopic of the iconoclastic inventor and auto-industry disrupter Preston Tucker—a quixotic genius brought down by his assembly-line-minded competitors—it was very obviously an act of self-portraiture. (Another of his on-screen doppelgängers: Gary Oldman as Count Dracula in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, an old-fashioned man trying to adjust to an increasingly newfangled world.) The title of 2007’s Youth Without Youth, meanwhile, suggested an old master nostalgically striving for naivete, an image of the sorcerer as apprentice very different from the majestic maturations of Spielberg and Scorsese, who played with form while stopping short of avant-garde experimentation. Coppola’s postmillennial work, though, went the distance: While not officially a trilogy, the films were more stylistically eccentric than the work of most contemporary auteurs (including the filmmaker’s own daughter, Sofia). In fact, the only real precedent for such aesthetic recklessness lay in their maker’s previous reviled passion projects. Say what you will about the sentimental fantasia of Youth Without Youth (about an elderly professor who de-ages after being struck by lightning) or the metafictional horror of Twixt (which features, among other things, several expressionistic 3D dream sequences and Val Kilmer’s Marlon Brando impression), but they are, if nothing else, Ones From the Heart.

The same would seem to be true of Coppola’s upcoming—and already legendary—sci-fi allegory Megalopolis, starring the patron saint of iconoclastic directors, Adam Driver, and featuring a supporting ensemble that seems to have been generated at random. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: Jon Voight, Shia LaBeouf, and Aubrey Plaza walk into a bar. The film, which is hotly tipped to be making its world premiere next month at Cannes, has already been described by industry insiders as “batshit crazy” and a “mix of Ayn Rand, Metropolis, and Caligula”— a fascinating and potentially fatal designation for a self-financed movie that’s been in the works for 40 years and whose budget is reportedly north of $100 million. (So far, no distributor has stepped up to the plate.) Given the material’s themes of excess and empire—with embedded parallels between the ruling classes of ancient Rome and contemporary America—it’s possible that Megalopolis will end up as a complement to The Godfather series, which remains one of the most steadfastly anti-capitalistic epics ever produced in the United States. But if we’re talking purely about artistic legacy, the movie that Coppola is chasing is the one that represents the most rigorous, vertiginous balance between his populist instincts and experimental intuition: 1974’s supremely and persuasively paranoid thriller The Conversation, a movie that defined its specific sociopolitical moment but that also somehow feels more pristinely and discombobulatingly modern than anything on the 2024 calendar.

It begins with a bird’s-eye view: a predatory perspective on San Francisco’s Union Square that renders the park in stark, almost geometric terms. Eventually, the camera begins zooming forward and down, a slow, deliberate movement that heightens the sense of documentary realism—a bustling urban scene observed at a distance—while introducing Coppola’s obsessive and claustrophobic theme of technological control. We’re not as free to look around as we think we are, and it’s not long before the shot isolates our protagonist, Harry Caul (Gene Hackman), who cuts a noticeably solitary figure in his slate-gray raincoat. Accosted by a mime, Harry refuses to engage, suggesting that his loneliness is by choice; the street performer, meanwhile, is a nod to Italian maestro Michelangelo Antonioni, whose 1966 art-house hit, Blow-Up, had been a beacon to so many emerging young American directors. In that virtuosic tour de force, a photographer poring through his own snapshots thinks that he sees evidence of a murder scene; in Coppola’s homage, a surveillance expert, the aforementioned Mr. Caul, comes to suspect that one of his field recordings contains garbled but distressing audio evidence of a potentially lethal conspiracy against two civilians. Haunted by his past complicity in a violent tragedy, Harry decides to figure out who’s trying to kill the people he’d taped in the park and why, effectively contradicting his own philosophies of distance and disinterest. “I don’t know anything about curiosity,” he tells a colleague. As it turns out, what Harry doesn’t know could kill him.

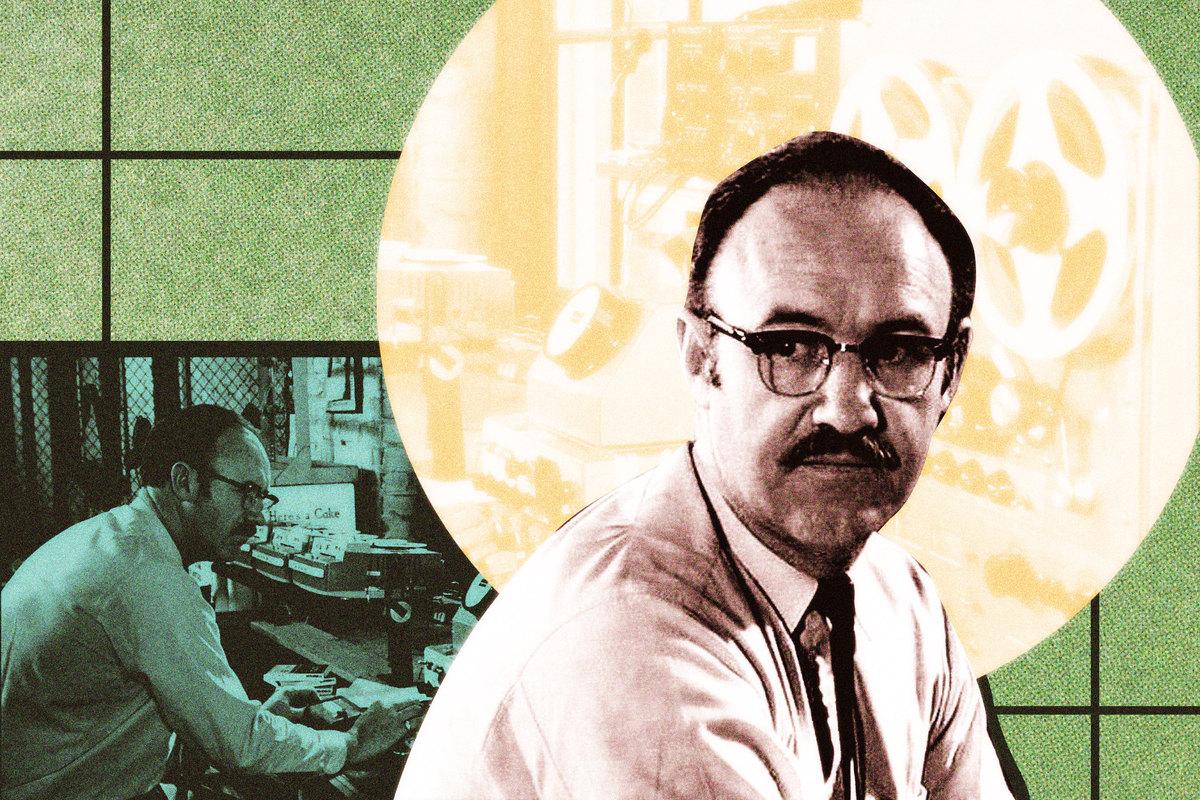

Ostensibly, the model for Harry was Martin L. Kaiser, a wiretapping savant who worked with the CIA and FBI and who also served as a technical consultant for Coppola’s film. Hackman plays Harry as a man who’s more comfortable talking about technology than his feelings; his longest conversations are with a priest, who receives his confessionals in stony silence. The idea of a cipher who intently listens in on other people’s conversations for lack of having much to say (or anyone to say it to) is an irresistible hook, and Hackman—who was coming off an Academy Award for playing the charismatic, two-fisted NYPD hero Popeye Doyle in The French Connection—gives an ingeniously introverted performance. Harry has repressed his desires so deeply that he can’t consciously connect to them. Instead, they’re lurking in the back of his mind through knots of sweaty, tangled, Catholic guilt. In one haunting sequence set against the backdrop of one of Harry’s chronic nightmares, we learn that he was sick as a boy and nearly died in the bathtub after being left alone by his mother, an anecdote that not only unlocks the character’s chronic moroseness but also connects him to Coppola himself, echoing the director’s childhood struggles with polio.

Viewed through this self-reflective lens, The Conversation deepens in resonance and complexity, revealing itself less as a riff on Antonioni than an expression of deeply personal ideas and anxieties around life and filmmaking. “[I] had heard of microphones that had gun sights on them that were so powerful and selective that they could, if aimed at the mouths of people in the crowd, pick up their conversation,” Coppola told Film Comment. “I thought: what an odd device and motif for a film. This image of two people walking through a crowd with their conversation being interrupted every time someone steps in front of the gunsight. … I began to very informally put together a couple of thoughts about it, and came to the conclusion that the film would be about the eavesdropper, rather than the people.”

The concept for The Conversation dates back to 1967, but Coppola waited to make it until the interregnum between the first Godfather pictures, citing a desire to work on something smaller scale. With this in mind, the sinister, enigmatic character of the Director—Harry’s employer, and a man implied to have a number of dizzyingly high-end connections—is legible as an analogue of an industrial power structure that Coppola has always tried to challenge or subvert. (Think of the gleeful, bloody satire of Hollywood casting practices in The Godfather, with its obnoxious A-list producer brought into line by the gift of a racehorse’s head in his bed.) That the Director is played by Robert Duvall cinches the conceptual link between the films, and a case can be made that, beyond Hackman’s impeccable anti-star turn, The Conversation features one of the best and most eclectic casts of the ’70s, including John Cazale, Frederic Forrest, Allen Garfield, Teri Garr, and an impossibly young Harrison Ford, who oozes menace as one of the numerous shady operators in Harry’s orbit.

As a piece of filmmaking, The Conversation is beautifully executed, with textured, tactile cinematography by Bill Butler, who would go on to shoot Jaws; carefully dividing the interior settings into squarish steel-and-glass frames, Coppola evokes the placid sterility of modern architecture only to pause for bursts of expressionistic splatter. (A toilet that spills over with blood during a hallucination sequence simultaneously looks backward toward Psycho and ahead to The Shining.) The almost subliminally precise editing is by Richard Chew and Walter Murch, the latter of whom was also responsible for the film’s phenomenally detailed sound mix, which turns the aural landscape of San Francisco into a character in its own right. In an interview with IndieWire, Murch explained that he and Coppola were primarily interested in questions of realism, starting with the Union Square prologue. “It was shot with hidden cameras,” said Murch, “and apart from the leads and a couple of plants, 90 percent of the people you see were captured in the moment.”

The overlay of authenticity on carefully structured fiction is the movie’s ace in the hole: The more naturalistic the presentation, the less the audience notices that they’re being manipulated. The Union Square scene provides Harry—and the audience—with the audio snippet that acts as both a narrative catalyst and an insidious source of misdirection. The pitch-black joke at the heart of The Conversation is that Harry’s preternatural skill at capturing sound—the instincts that make him, in the words of a colleague, “the best bugger on the West Coast”—doesn’t give him the ability to interpret it properly. Slowly, that conjoined, paradoxical sense of authority and confusion boomerangs back on the viewer, whose understanding of events is carefully filtered through Harry’s own (ultimately mistaken) perceptions. Like Roman Polanski’s Chinatown—which was released the same year—The Conversation is a movie about a character whose own brilliance becomes a liability because he can’t see (or in this case, hear) the bigger picture. The two films also share a theme of institutional corruption that couldn’t have been more timely, but where Polanski’s neo-noir used the social and political topography of the 1930s to critique rapacious late-capitalist practices, Coppola’s artistic antenna channeled a zeitgeist in which secretly recorded audiotape was understood as a kind of smoking gun. That the film hadn’t actually been inspired by Watergate or the Nixon tapes didn’t matter. In a moment when surveillance tech was becoming interwoven into every aspect of daily life, The Conversation quickly became a conversation piece—an allegory about the collapsing gap between a generation’s public and private lives.

In 1998, director Tony Scott cast Hackman as a surveillance expert opposite Will Smith in Enemy of the State, sparking fan theories that the character was an alternate identity for Harry Caul. It’s a funny notion that suggests the depth of the late action auteur’s cinephilia, but it also undermines the devastating finality of The Conversation’s closing scenes, which rank among the darkest endings of the 1970s. Without completely spoiling the film’s plot—which is itself really just a pretense for Coppola’s fine-grained and unsentimental exercise in character study—it can be said that Harry comes out on the losing end. However malevolent the larger forces around him may be, the film is ultimately a story about a man disappearing into a rabbit hole of his own making. No matter how many careers Coppola has, he’s unlikely to match the potency of this coda: The manic yet methodical energy with which Harry goes about (literally) dismantling his own little corner of the world—in search of a bug that may or may not exist—provides an indelible image of physical and psychological ruin. A heartbreaking, blood-chilling glimpse of the expert (or maybe the artist) as a helpless, compulsive prisoner of his own devices.

Adam Nayman is a film critic, teacher, and author based in Toronto; his book The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together is available now from Abrams.