Juan Soto Changed Everything for the Yankees. Will They Change Their Ways to Keep Him?

Soto’s transformative impact since being traded to New York is unmistakable. What comes next—both for the Yankees’ 2024 fortunes and for their contract extension talks with the young star—will reveal just how far that impact extends.

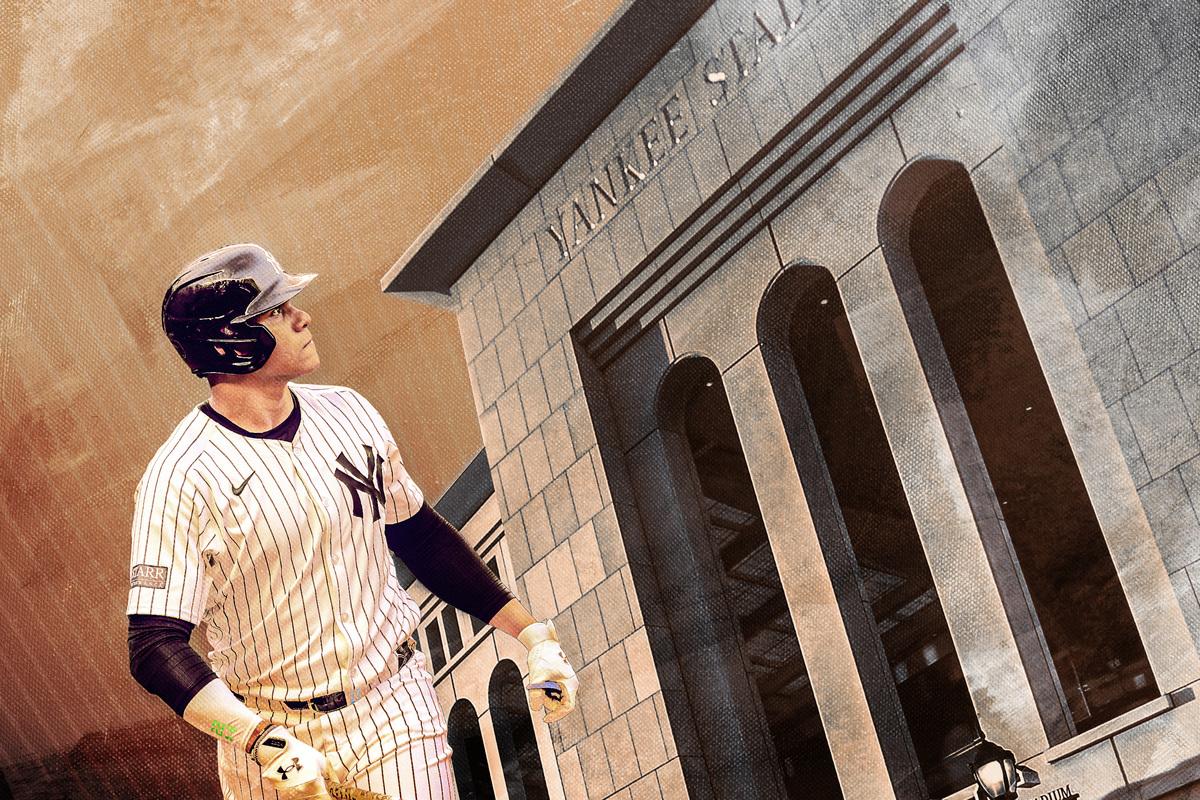

The stares float through the stadium with the pollen currents well before the newest star in pinstripes steps onto his chalk and clay stage. During pregame stretching routines in April and again in May, Juan Soto—the most talented New York Yankees trade addition since Alex Rodriguez—exists in a Bronx-made fishbowl. Children stand in oversized jerseys and point. Adults put down their cellphones, their heads on a swivel. The bleachers buzz with anticipation by the time the self-proclaimed “generational” talent enters the on-deck circle toting at least one 34-inch maple-wood bat.

Soto’s conduct in the batter’s box—his shimmying, smirking, peering, nodding, lip licking, tongue wagging, and (formerly) crotch grabbing—is often likened to that of an artist at work. Soto not swinging a bat is the closest thing to merengue that can be found on a baseball diamond north of the equator. But what is difficult to convey to those who are not up close and personal is the degree to which his flair mirrors the pageantry of arena conflict. Soto’s performance, like those of gallant matadors, feels as much about how what’s happening is observed as about what’s happening in the first place. Each one of his at bats in Yankee Stadium evokes more than just giddy anticipation or outright appreciation. In the eyes locked on Soto from every direction, there is also a shared sense of disbelief.

There’s something going on at East 161st Street, and this is part of it. The suffering in the Bronx appears to have ended. There is good baseball afoot. Nature found a way. Or Soto did. Best not to overthink it.

Nearly a third of the way through the 2024 regular season, the New York Yankees are 35-17. They’ve swept as many teams in eight weeks as they did all of last year. They lead the perennial death trap that is the AL East by three games and, coincidentally, they have the best record in the American League. They are, in the words of platinum-plated left fielder Alex Verdugo, “some dawgs” in the batter’s box. They take more pitches than all but three teams. Nearly every at bat has claw marks all over it. As a collective, they rarely appear to contemplate weakness.

These are descriptions of the team, but they could also fit snugly as characterizations of a certain slugger in a no. 22 jersey. The springtime truth of this year’s Yankees is that they’re past beginning to resemble Soto as much as he resembles them.

There is material and philosophical meaning to this. The material: In New York’s season-opening sweep against the Houston Astros, Soto upended a half decade’s worth of pantsings by the Yankees’ trash-can-banging rival, culminating in a surgical outfield assist followed by a game-winning single against big-money strikeout merchant Josh Hader. (It was less of a hit than a designed deflection.) The philosophical: A few weeks later, in the middle of another New York pass-the-baton offensive hot streak, manager Aaron Boone told reporters that although this is who the Yankees “always have kind of wanted to be as an offense,” things had come together in part “because of his”—meaning Soto’s—“presence.” They swing at strikes; anything off the plate is greeted with spit; bad umps are shit talked.

It’s not that Soto has single-handedly reshaped the team in his own image. It is, though, a sign that the team has taken on bits and pieces of him in ways that stretch beyond conscious intention. This—more than the walks, the homers, or the plateside shuffles—is the strongest argument for his transcendence as a player. And if front-office frugality under the guise of financial sustainability has its way once more, it still may not be enough to keep him from being sent packing from his third MLB home.

Soto is exactly the kind of player who is never supposed to come on the market. Yet this weekend he will play for the Yankees, his third team in three years, against the San Diego Padres, the organization that sent him to New York as part of a package deal primarily meant to create “financial wiggle room.” Soto is 25 and one of the best pure hitters the game has ever seen. That he has gone from Washington to San Diego to New York before even reaching his prime is an indictment of the team-building dogmas and structural health of baseball in the United States.

After all, Soto as a figure, player, and competitive force is unlike even his most talented peers. And this includes the moon-shot colossus who sets up shop 50 feet over from him on a daily basis, in center field.

There is no good way to convey how herculean Aaron Judge appears in person, particularly alongside his Yankees teammates. He is a titan of marbled physique and unrivaled productivity. He’s got that chest thing that cartoon superheroes have where they look like upside-down triangles. Get close enough to the field, and you’ll swear he makes Giancarlo Stanton look small. Judge’s greatness is, in this way, unrepeatable. You cannot teach height. You cannot summon otherworldly arm strength. You cannot grind your way to having a preternatural baseball IQ. Judge, like other Yankees captains before him, exists in his peers’ eyes more as a standard than as a man—and that standard exists to never be met.

Soto’s salience both on the field and in the clubhouse is different. He toes the line between aspirational and relatable. He is the type of pragmatist who (with more than a bit of pushing from his superagent) rightly concluded that a reported 2022 offer for a 15-year, $440 million contract extension from the Washington Nationals was below market value for a historically precocious hitter. He is also the type of full-fledged romantic who cried for a day when greeted by the fallout from that decision—the trade to the Padres that August—and who admits he never wanted to leave the Nats. Soto still refers to his World Series champion 2019 teammates as “family,” before adding, “it will never be that way again.”

His journey through and out of the Latin American baseball-industrial complex likewise aligns him with a plurality of players in the majors and minors, even while the pace of his ascent put him on a plane reached by only a few. Comb through Soto’s origins in the Santo Domingo neighborhood of Herrera in the Dominican Republic—its cramped and crumbling infrastructure, its exploitation at the hands of dictatorships and U.S. financial interests—and you’ll see the common language of athletics as a so-called tool of upward Caribbean mobility. Anecdotes about Soto using glass bottles and caps as crude substitutes for bats and balls echo the come-ups of other Latin greats. (To say nothing of how the system of amateur ball on the island—a complex web of regional clubs and MLB-owned private academies—reflects all the lives shaped by the long use of baseball as a tool of U.S. imperialism.)

The succeeding facts of his career, though, differentiate him from his peers. It took Soto only 122 minor-league games before the Nationals called him up as an injury replacement in 2018. His MLB on-base percentage ranks 20th all time, one spot behind Mickey Mantle. Soto is one of four players since World War II with an OBP of at least .421 over a minimum of 2,000 plate appearances. He’s the best young postseason hitter since Miguel Cabrera; he clubbed more World Series homers by age 25 than multiple first-ballot Hall of Famers have during their entire careers. Oh, and he’s on pace to hit more than 500 homers if he plays only until he’s 35. He has 13 on the season and hit two on Wednesday against the Seattle Mariners.

This same pattern of rare ability and reliability shows up when it comes to how he plays. Soto’s hitting process and philosophy are steeped in routine. He eschews tip-pitching recognizance. He’s distilled his strike-zone ethic down to a simple proverb: “If it’s not a pitch where I can do damage, I don’t swing.” His stance is compact and thoroughly rehearsed. To hit breaking balls, he took thousands of reps on a broken pitching machine. To avoid excessively pulling the ball, he practices spraying hits to every side of the field on a daily basis.

Listen to the remarks of those around the game, and Soto sounds like a batting demigod. Gerrit Cole, Soto’s now-teammate, whom he once tattooed for multiple home runs in the 2019 World Series, says the 25-year-old’s eye for balls and strikes is unrivaled. Judge refers to Soto as “the greatest hitter out there,” in the same way that a wine connoisseur might talk about a vintage of 1962 merlot. When Soto was a rookie, his then-teammate Max Scherzer said of his two-strike approach, “There’s no one way to approach Juan late in counts.” Former hitting coach Kevin Long talked about Soto as if he were the second coming (“I’m blessed and fortunate to be able to see this”), and current Yankees assistant Pat Roessler—who’s been working for MLB teams since the late ’80s—recently said of Soto: “Nobody I’ve seen squares the ball up like him.”

Each of these threads weaves together a quilt of, well, generational greatness. When he was the same age most baseball players are when trying to navigate the pipeline to the big leagues, Soto proved that he’s capable of being both the best of them and simultaneously just one of them. He has a singular capacity to rub off on his teammates. He does his job so well, and so infectiously, that those around him can’t help but get swept up in his spirit, trail his seen and unseen currents.

And still, his future with the Yankees remains uncertain. Not because Soto is unwilling to negotiate an extension during the season—“They know the phone number and everything,” he told reporters when asked about that earlier this month—but because of the state of baseball. He can change the culture of a clubhouse virtually overnight, but he might not be able to change how those who run the franchise operate.

Whatever summer magic Soto and his teammates conjure in the Bronx might not result in a storybook ending, let alone a long-term partnership. Sure, we have evidence of intermediary flirting. We also have evidence of 1 percenter hemming and hawing. Baseball has always been a game of cascading uncertainties where even the best players fail more often than they succeed. The odds are stacked against you, but its appeal is what players like Soto can deliver: the ability to stop time and suspend belief. What if this time the odds flip? What if now things are different?

Something is happening off the Harlem River with the guy wearing no. 22 and the ball club he plays for. Right now the currents mean only so much. Soon enough, they might mean everything.