Creature Feature: The Oral History of ‘Gremlins’

Don’t feed them after midnight. Don’t get them wet. But do read this deep dive into Gizmo and the nasty Gremlins, featuring words from director Joe Dante, actors Phoebe Cates and Zach Galligan, and many more.Of all the valuable life lessons Gremlins has taught us, two are most important:

1. Society needs rules.

2. There’s nothing more fun than breaking them.

That contradiction is the movie’s oozing heart. Because of human ignorance, the cutest creature on earth spawns an army of slimy monsters. But even as the reptilian goons terrorize the small town of Kingston Falls, it’s hard for the audience not to cheer on the mayhem.

“The Gremlins themselves are creatures that adhere to nothing except their own momentary, impulsive desires,” says Zach Galligan, who plays Billy, the (human) star of the film. “They’re essentially Freud’s version of the id. It’s just, ‘Whatever you want to do, they do.’ They’re anarchists, quite honestly. They don’t follow any rules. And I think that not only 10-year-olds, but I think secretly a lot of 40- and 50-year-olds love that idea and live through the Gremlins vicariously.”

Since its release 40 years ago this week, Gremlins has appealed to our base instincts. But what makes it a classic is that there’s far more to it than its core of silly madness. Director Joe Dante threw horror, science fiction, slapstick, satire, family drama, and holiday nostalgia into a blender and pushed the puree button. Amazingly, the swirl of green goop he created congealed and formed a masterpiece—one that’s both madcap and governed by a specific set of rules that people still remember today.

“Somebody once said to me that I make movies and the MAD magazine parodies of movies at the same time,” Dante says. “That was a big influence on me, MAD magazine. And so all the movies that I’ve done have a certain absurd take on the material.”

Comedian Howie Mandel, who voices the heroic furball Gizmo, saw an early cut of Gremlins while recording his lines. To him, it was completely unclassifiable. “I kept watching it and I kept thinking—because I didn’t know—‘Is this really a kid’s movie?’” he says. “It’s kind of dark and funny and scary and Christmas-y. It’s like everything. It’s like four different genres at once. And to my surprise, it even was so indescribable that it created its own rating.”

More on that last point later. First, let’s tell the story of how Gremlins transformed from a low-budget picture populated with puppets to the third-highest-grossing flick in America in 1984, behind only Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and Ghostbusters. Getting there was at times nightmarish, especially for Dante and his visual effects team. Making the creatures look believable required nonstop tinkering. The animatronics broke down constantly.

It was frustrating but fitting. In the film, Billy’s father, Randall, is an inventor of gadgets that look neat but are really junk. “It’s sort of a whole trope in the whole movie: Nothing works,” Dante says. “I mean, it’s all about entropy. Nothing in the movie that’s supposed to work, works. Including the Gremlins, often.”

Yet Gremlins overcame Murphy’s Law. How? Well, it didn’t hurt having a young executive producer named Steven Spielberg on board. And it helped that, while everything around him was going haywire, the funhouse architect stuck to his plan. Even if he had no idea whether it would work.

“When you’re doing a picture like this and you’re getting into the far fringes of weird stuff that isn’t usually done in movies, you always have to just sort of step back and say, ‘Now am I doing this just because I think it’ll be funny or will other people think it’s funny?’” Dante says. “And sometimes you never know.”

Part 1: “Spielberg’s Folly”

Like many successful baby boomer filmmakers, Joe Dante got his start in Hollywood working for B-movie king Roger Corman’s New World Pictures. Dante’s first solo directing job, the low-budget, self-aware Jaws rip-off Piranha, hit theaters in August 1978. With Jaws 2 also coming out that summer, Universal Pictures actually threatened to file an injunction to block its release. Luckily for Dante, Steven Spielberg saw the winking movie, liked it, and helped stop a potential lawsuit.

Soon after that, Spielberg started his own production company. In the early 1980s, he hired Dante to direct one segment of the big-screen adaptation of The Twilight Zone. Around 1982, Spielberg also took an interest in a script named for the mythical, destructive creatures Royal Air Force pilots made up to explain mechanical failures. In the screenplay, written by future blockbuster comedy director Chris Columbus, adorable little guys called Mogwai—an English version of a Cantonese word that roughly translates to “evil spirit”—turn into Gremlins.

Michael Finnell (producer): Chris Columbus, when he was a film student at NYU, lived in a crummy apartment like we all did as starving students. And he would hear mice in the apartment, running around. He realized that most monster movies, Godzilla, King Kong, the monster’s big. But in a way, something small is scarier because they can hide. So he came up with this idea and he wrote this spec script. Somehow it got to an agent and CAA sent it out as a writing sample because they thought that nobody would make it. It was just too nuts.

And it ended up on Steven Spielberg’s desk at Amblin Entertainment, which was the company that he had just started with Frank Marshall and Kathy Kennedy, and they wanted to produce movies that Steven didn’t necessarily direct. So he read it, and not only did he say, “This guy can write,” he said, “I want to actually make this.”

We were trying to figure out what to do next, and we actually were playing with a project called The Philadelphia Experiment, which ended up getting made by somebody else. But then our agent, David Gersh, calls and says, “Steven Spielberg wants to send you guys a script.” I was like, “That’s interesting.”

Joe Dante (director): I got the Gremlins script in the mail, which I assumed had gone to the wrong address.

Finnell: We’re in our crummy office in Hollywood and the script shows up and every page is stamped with a code so you can’t Xerox it. It had to be top secret.

Dante: When I read the original draft of Gremlins, which was a grade-B horror movie that was really R-rated, I thought, “Well, sure.”

Finnell: Steven had seen The Howling, which was the low-budget werewolf movie that Joe and I had made.

Dante: Not only seen The Howling, he had cast the lead actress in E.T.

Finnell: He really liked it, and he thought that the mixture of horror and comedy was what he wanted for Gremlins.

Dante: Because he was looking at his first Amblin as a horror movie, he figured, “Let’s get this guy who made these two horror movies.”

Finnell: We read it and we both look at each other and say, “Well, this is great, but impossible to make.” The first draft was the Gremlins running around all over the place, and it was all set during Christmas in the snow.

Dante: It became apparent that in order to make these creatures look believable for a whole movie, it was going to have to cost some money.

Finnell: But we’d be nuts not to take it to the next step. so we told David, “We would love to meet with Steven and see what he has to say.” So we did, and he was actually in the middle of postproduction on E.T. and Poltergeist. We went to Warner Hollywood at the time. He had to come outside because we couldn’t go in and see anything on the screen. So he comes outside and we were in the parking lot leaning against the car. The meeting couldn’t have been more than 15 or 20 minutes. Basically at the end of it, he said, “OK, great. Let’s do it.”

Dante: We went to the studio at Warner Bros., and they were thrilled to get a Spielberg movie, even though they didn’t have any idea what it was about. They could not figure out why they wanted to make this movie, but they said, “Great.” The word around the lot was “Spielberg’s Folly.” That was how they basically looked at it.

Finnell: I called him up and I said, “So Steven, what should I do?” And he said, “Call Lucy Fisher at Warner Bros.” And Lucy was an executive at the time. She later became a copresident of the Producers Guild and a producer in her own right. And so I called her and she said, “Come in for a meeting.”

Lucy Fisher (executive vice president of worldwide production, Warner Bros.): It was below the studio’s radar. And the whole time we were making it, Columbia was making Ghostbusters.

Finnell: Of course, they were three times as expensive as us. We were $11 million and Ghostbusters was over $30.

Fisher: That was the comedy movie that everyone was paying attention to and had all the red-meat stars and had all the big shots. And we were just the little thing that nobody quite understood what it was.

Finnell: And that began a very lengthy process of developing the script. For two reasons. One was that the first draft was funny but really violent. There was one scene where Billy and Kate go into a McDonald’s and all of the people are half eaten, but the burgers are untouched. I mean, they killed the mother and the dog. We wanted to be PG, it was definitely R at that point.

Dante: Not only was it a horror movie, but the lead character was 12 years old. They said, “To make it for Warner Bros., we’ve got to bump up the ages, this has got to appeal to teenagers.” But all the storyboards I did are all children.

Fisher: As a studio rep, I was the cover for them that was always trying to broker things that were pretty hard to explain.

Like the three rules of caring for a Mogwai. Let’s let the grandson of the Chinatown shop owner who sells Gizmo to Randall Peltzer explain:

1. “Keep him out of the light. He hates bright light, especially sunlight. It’ll kill him.”

2. “And keep him away from water. Don’t get him wet.”

3. “But the most important rule, the rule you can never forget, no matter how much he cries, no matter how much he begs, never, never feed him after midnight.”

Fisher: I remember very well trying to justify it to our business affairs guy—who I was at war with—about every single thing I tried to do. He would go, “Well, what does that mean, after midnight? If it’s 6 in the morning, is that still after midnight? I don’t understand the rules.” I go, “You don’t have to.”

Dante: They’re so arbitrary. I mean, let’s face it. One thing that we figured is if people don’t buy this, they’re not going to buy the movie. The idea was that if they go for this, then they’ll sit and watch the movie. It was like, “OK, if those are the rules and you guys play fair, then we’ll let you get away with it.”

Finnell: The other thing is we had to rewrite it to make it possible to make in 1984. It all had to be done practically.

Dante: Jim Henson had been doing some movies like The Dark Crystal, but this was a completely different situation. You had all these characters and they had to do all of these things.

Finnell: The first thing was to find somebody to create the Gremlins.

Part 2: “He Bounced Around the Editing Room and Shit All Over Everything”

Finnell first called Rob Bottin, a now legendary special effects and makeup wiz they’d worked with on The Howling. But he was busy with Ridley Scott’s Legend. So the producer decided to reach out to another one of Dante’s former collaborators.

Finnell: Chris Walas had actually worked on Piranha, Joe’s first feature as a director, so he knew Chris. Plus, Chris had done all the melting, exploding Nazis at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Chris Walas (creature creator/supervisor): I was on this series of fall-apart productions, and Joe and Mike called me up. Universal was going to do a 3D remake of Creature From the Black Lagoon. And so they wanted me in on that. And then Mike just calls up one day and he says, “So, Chris, Universal has decided to go with Jaws 3D instead.” I’m like, “Oh my God.” In the meantime, I’m looking at my mortgage bills. And then Mike says, “But there’s this other script we’d like you to take a look at and see what you think of it, because we’re not sure.” I said, “Yeah, sure, I’ll read anything.” So they sent the script up, and of course it was completely insane and impossible.

Dante: There’s a whole group of effects guys who all worked on Star Wars at the time and were fanning out in Hollywood. Rob Bottin was one of them, and John Dykstra. All these people who were getting in on the burgeoning effects industry, which was really ramping up at that time. And Chris was one of the best.

Walas: When Joe asked me to basically take charge of the creature effects, I was kind of going, “OK, that sounds great. I love creatures.” But it was odd at the beginning because it wasn’t just designing the characters, it was figuring out how we were going to do them all. Joe wanted to do everything stop-motion at first because he’s a huge stop-motion fan, which I am as well, but I’m just like, “Joe, do you understand how much stop-motion you’re talking about?” And he did. He understood. And then he had the idea of dressing monkeys up in costumes.

Dante: It’s hard to believe, but yes, it is true.

Finnell: We had a trainer come in with a monkey and everything, and Chris said, “No way. No way am I going to be able to put a Gremlin’s costume on this thing.”

Dante: We got a rhesus monkey and put a Gremlin’s head on him, and he bounced around the editing room and shit all over everything. And it became quite apparent that this was not the way we were going to do it.

Walas: That pretty quickly convinced Joe to go with my line of thinking, which was puppets. I always loved puppets. I still love puppets. But that also posed its own challenges. At that point with the technology, which we were essentially creating at a time, we didn’t have the developed resources that came later in puppetry in the business. I took the approach that there’s not going to be an easy way to do this, right up front. You have to convince yourself, “Don’t try to cheat this one because there’s just way too much going on.” And so I went with the whole concept of just creating a ton of puppets.

Dante: It was a rather arduous task because there had never been anything done with puppets at that scale.

Finnell: Chris Columbus had done some drawings. He was really a talented kind of cartoonist, and so was Joe. But Chris had drawn what he thought [the Gremlins] should look like, and it was the big ears. I mean, it was very similar to what we ended up with, obviously with a lot less detail.

Walas: I had this meeting with Steven and Joe, and we’re there talking about the nature of the Gremlins. And it was really funny because Steven’s just kind of like, “They should be really nasty and hunched over.” And I’m like, “Yeah, that’s what I’m thinking for the pose.” And they walk around—more like hopping—and Joe’s like, “Yeah, and then they do THIS.” And there’s three of us jumping and hopping around the coffee table like lunatics.

Dante: There were things in the script that the puppets couldn’t do.

Fisher: The poor guy Gizmo couldn’t walk.

Dante: He’s got to be carried around in a backpack.

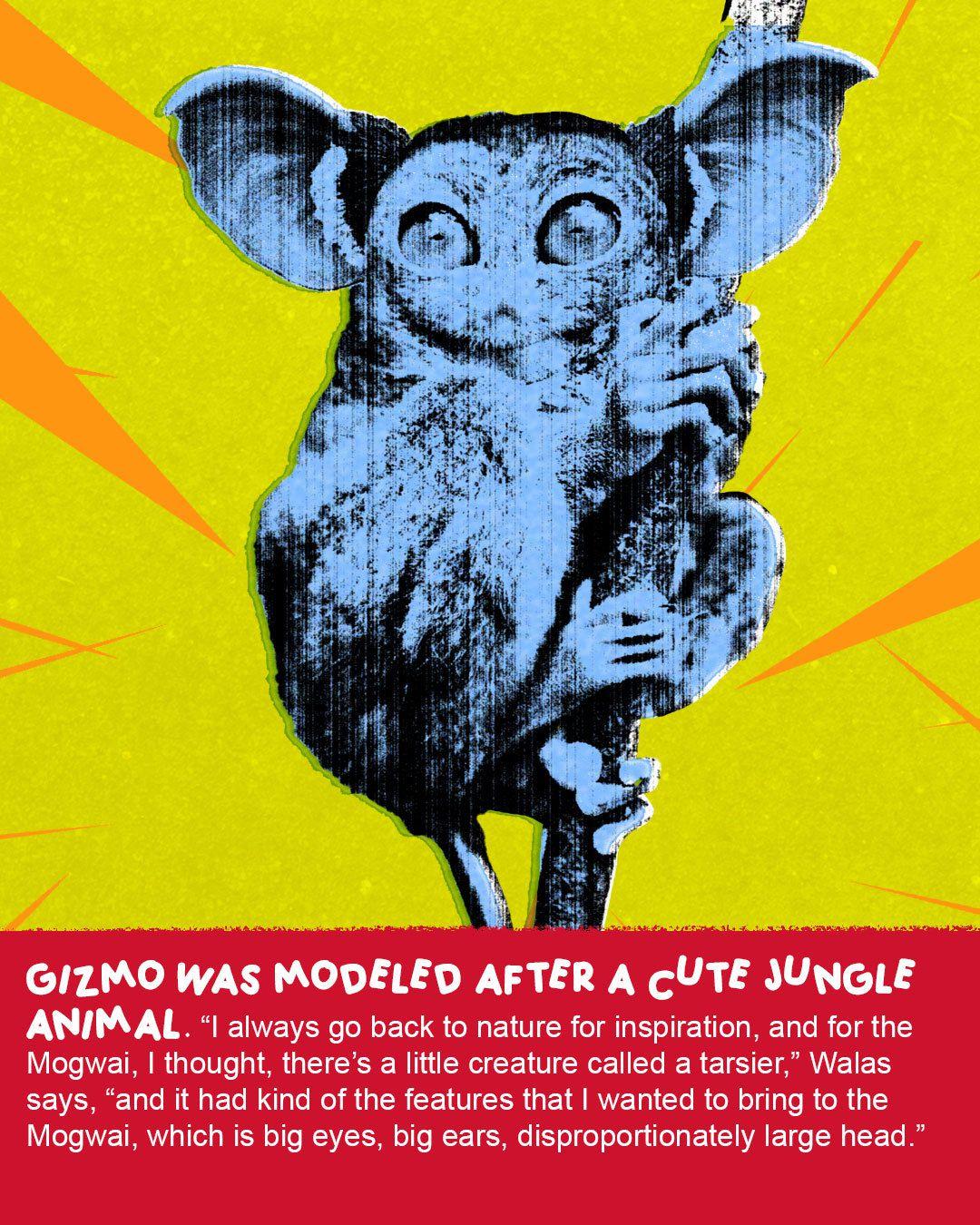

Walas: I always go back to nature for inspiration, and for the Mogwai, I thought, there’s a little creature called a tarsier, and it had kind of the features that I wanted to bring to the Mogwai, which is big eyes, big ears, disproportionately large head. And I’m thinking here practically: The bigger I can make these elements, the easier I can make the puppets work. And so that was kind of the starting point. And I did a couple of very rough napkin sketches.

Fisher: We didn’t have the name and then it came up. Somebody was referring to the puppet as “a gizmo.” “Get that gizmo over here.” There you go.

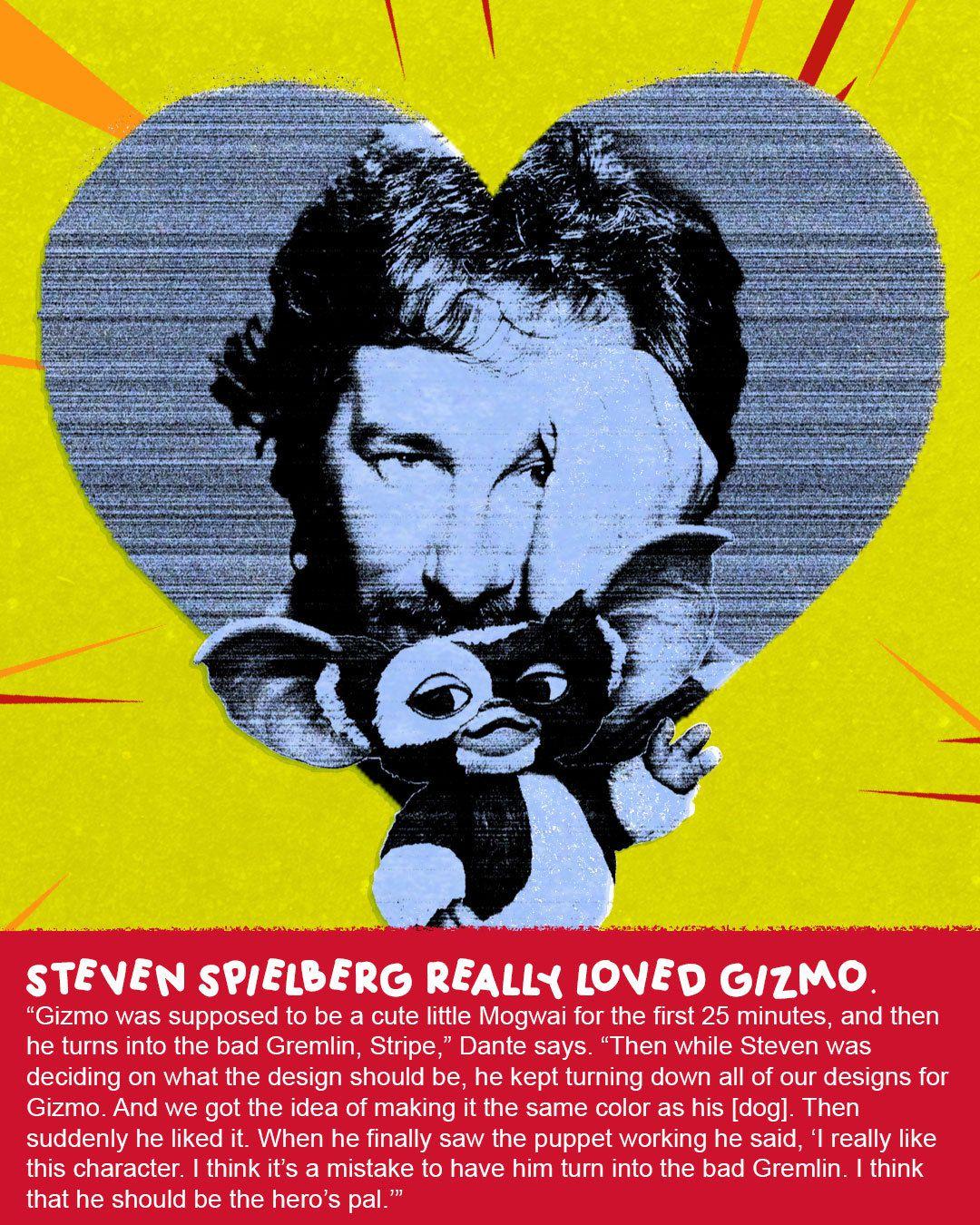

Dante: In Chris Columbus’s original script, Gizmo was supposed to be a cute little Mogwai for the first 25 minutes, and then he turns into the bad Gremlin Stripe.

Finnell: And there’s no Gizmo for the rest of the movie.

Dante: Then while Steven was deciding on what the design should be, he kept turning down all of our designs for Gizmo. And we got the idea of making it the same color as his [dog]. Then suddenly he liked it.

Fisher: Steven’s intuitive thing is he knows where the pleasure is, and some people want to avoid the pleasure because they think that that’s pandering. But he embraces the pleasure moments and he’s always figuring out how to make something more dramatized.

Dante: When he finally saw the puppet working he said, “I really like this character. I think it’s a mistake to have him turn into the bad Gremlin. I think that he should be the hero’s pal and he should be in the whole movie.”

Walas: That meant way more puppets and character stuff all the way through the film now.

Dante: This is two months before we were going to shoot, and there was no way we were going to get this little bucket of bolts to be interesting and mobile enough to be able to carry a movie. So we had to build giant versions of the puppet with huge heads in order to get the close-ups and get the emotion.

Walas: I think the real draw for Gremlins is that it’s a dichotomy between this cute sweetness of Gizmo and the wholesome nature of Kingston Falls, and then these just psychotic, mischievous creatures that are just screwing everything up.

Dante: I still believe, to this day, that one of the main appeals of that movie is Gizmo.

Walas: We did a series of these puppets and we did a whole bunch of video tests, and it’s just three or four or five of these puppets, and they’re just throwing things around, hitting each other. And that was our creature makers’ first insight into what these characters were going to become. Because when you start playing with puppets, things kind of go crazy. It suddenly becomes, “Hey, this is fun.” It becomes an improv session. So that was a good step forward in the creation, not of the puppets, but of the characters.

Finnell: Terry Semel, who was the president of Warner Bros. at the time, was very concerned, rightly so, about how realistic these things would look. He was like, “Are people going to laugh these things off the screen?”

Walas: As soon as we had the molds for the Gremlins finished, the studio wanted to see another test. And they were like, “We’re coming up on Friday.” And I’m like, “We can’t have a puppet ready by Friday. That’s three days from now.” And so I went about 40-something hours without sleep to pull a puppet together, a mechanical animatronic puppet. And Joe came up, Mike came up, [director of photography] John Hora came up, [producer] Kathy Kennedy was there. And we just shot a whole bunch of stuff. Just random stuff. And Joe managed to cut it all together somehow, I don’t know how he did it, and showed the studio. And based on that, the studio kind of went, “This could work.”

Finnell: Lucy calls us and says, “Come up to the office.” And we go, “Oh my God. Dammit, is it good or bad news?”

Fisher: I went out to the hardware store and bought a green light and put it in a little box. I was so excited to tell them. I wanted to make a little ceremony.

Finnell: We go into her office and she has a cardboard box. She opens it up and there’s a light bulb in it painted green, meaning green light. Here’s the green light. It was like, “Oh, thank God.”

Walas: Mike calls me up and says, “Hey, good news, we’ve got the green light.” And I’m like, “What? We didn’t have the green light?”

Part 3: “We’ve Got to Cast Him. He’s Already in Love With Her.”

Gremlins had its creatures. But it also needed real people. The cast is filled with character actors like Dante good-luck charm Dick Miller, who plays Gremlin-fearing World War II vet Murray Futterman. Except for Phoebe Cates, who was coming off Fast Times at Ridgemont High, no one was on the Hollywood A-list. Preteen idol Corey Feldman appears as the precocious neighborhood kid Pete. Singer-songwriter Hoyt Axton is the loving but slightly harebrained head of the film’s nuclear family. Frances Lee McCain, who also plays moms in iconic ’80s movies like Footloose, Back to the Future, and Stand by Me, is Randall’s wife. The part of their almost-grown up son, Billy, went to an unknown: Zach Galligan.

Dante: There’s always a desire to try to get people who are going to bring people into the theater. But on the other hand, the studio was quite aware that this was not going to be a star vehicle. But they were good parts and it was a Spielberg movie, so of course they all wanted it.

Corey Feldman (Pete Fountaine): Steven and I had already met when I auditioned for E.T. He wanted me to be one of the two stars of the movie. And then he went dark and he just kind of disappeared for three months. And then all of a sudden, we get a call. “Steven wants to talk to you.” It’s on a Saturday.

He’s like, “Unfortunately, I have some sad news. There’s been a major rewrite of the script. And we’ve decided to change the idea that this movie is about a little boy and his friend who discover an alien, and we’ve made it a little boy who discovers the alien on his own and tries to hide it from his family. So unfortunately, whatever part you are going to be doing as the best friend, it’s going to be cut down to a day or two, and we think that would be a waste of your efforts. So I would advise you to withdraw from the role. And I promise if you do that, I will give you a lead role in whatever my next film is that has a kid in it.”

I’ve heard this kind of thing a million times before in this industry. Like, “Oh yeah, sure, you’ll be in my next movie. No problem.” And then that never happens. But Steven kept true to his word, and about a year later I got a call that he was doing a movie called Gremlins. So I went in, I read for Joe, and the rest is history.

Dante: We already knew who he was because I’d seen him in Time After Time. I’d seen him in a whole bunch of pictures. And when you’re looking at child actors, you want to find the ones who actually are professional and don’t have the Disney Cutes.

Frances Lee McCain (Lynn Peltzer): I had just done, relatively recently, Albert Brooks’s Real Life. And I know that Spielberg and Albert knew each other. It was a wonderful moment for me because I wasn’t the happiest person in the world at that time. And I got a call to do a meeting with Joe and Mike Finnell and I had a great time. We just sat and talked to each other and just really enjoyed the conversation. And I love being around nerds and film buffs, and these guys were that.

Dante: I saw Hoyt in The Black Stallion. I heard his music and I liked him. But when I saw him in that picture, I just said, “This guy is really a good actor,” and he’s so folksy and he’s playing a guy who’s kind of a ditz and in fact, would be in another version of this movie kind of unsympathetic.

McCain: This was a family of three people who really loved each other and really enjoyed each other, got each other’s foibles, and just went with the flow. And I thought it was brilliant casting when I was first told about the casting of Hoyt. I thought, “Well, that’s interesting.” And then he was the easiest guy to be around.

Zach Galligan (Billy Peltzer): You have this whole idea of following rules and how the world needs an organized, competent structure, and then you have Hoyt, who’s just … nothing works. So it’s the battle between the theoretical competency and the actual incompetency of humans.

McCain: She just loved this guy, and she loved all his little quirky things. All his little attempts to make the great thing that would pull the family up by the bootstraps.

When he read for the movie, Galligan had never been in a feature film. The New York City–raised teenager, however, had been acting for years. He didn’t know it at the time, but an earlier audition, set up by casting director Juliet Taylor, helped him land a role of a lifetime.

Galligan: She called me out of the blue and had me audition for this Paul Mazursky movie with John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands called Tempest. And that was the most important audition, probably in my life. It’s my first actual professional audition with a director. And they wanted to pair me with girls to see if we had any chemistry, it’s called a mix-and-match session. The first girl I read with was Erzsebet-Liz Foldi, who played Roy Scheider’s daughter in All That Jazz. And the next person they had me read with was Phoebe Cates. So she came in, and I had seen her on the cover of Seventeen magazine. And when she walked in, I was like, “Holy smokes.” She and I read, and she was fun, and she did the fun giggly thing. She had the “I’m not even remotely nervous to be in this room” type vibe thing, which is so crucial.

Phoebe Cates (Kate Beringer): I was a working kid. I did my first part in a television show at 10. And then commercials and modeling. And so by that time, I’d done a couple of movies. I was getting offered a lot of stuff.

Galligan: I’m clenching my papers and script with white knuckles, probably sweat pouring down my armpits. And I just was like, “Wow, I think we hit it off pretty well.” And I read four or five times after that. They really made me go through hoops. And I didn’t get it, but Juliet basically was like, “You should really try and do this.” Juliet helped me get an agent, and I was off and running. So when it came to the Gremlins audition, I walked in, I read for Susan Arnold, the casting director, straight through. Read for Mike Finnell. He loved what I did and was like, “Joe, you’ve got to see this guy.” Called me back two days later, I walk in, it’s another mix-and-match session. Who do they pair me with? Phoebe Cates.

Cates: When I read the script, it was like an immediate, “Yes, I want to do this,” because I’d always been a fan of horror and sci-fi, and horror-comedies. It started for me when my father was working in France and the family was there for the summer. And he took me to see Soylent Green, in French, but with subtitles. And I remember loving it. It opened this whole world. The movies I loved most were Trilogy of Terror and Piranha, you know what I mean? So now there’s an opportunity to be in one of those kinds of movies. And it really made me laugh.

Galligan: She’s chewing her gum with her hair in a ponytail, loose as a goose. I’m panicking. And she’s like, “Are you trying out for Gremlins?” I said, “Yeah.” She patted the chair next to her and she’s like, “Sit next to me and let’s read together.”

Cates: It just felt like we’d kind of known each other forever. I do remember reading with him. And I remember thinking, like, “Oh, this would be so much fun to play this girl.” Especially having done Fast Times, and being a little bit of a New York, kind of savvy kid.

Galligan: Everything needed to happen perfectly in order for me to get this movie.

Dante: A bunch of people read for that. Tom Hanks, I remember. Emilio Estevez.

Finnell: Tom Hanks [also] read for Gerald—the slimy bank manager—that Judge Reinhold played. He bugged us, when we did The ’Burbs, he said, “You didn’t hire me for that.” But the reason was is he looked too much like Zach Galligan, and we thought he had the same curly hair and everything.

McCain: Zach had just a beautiful, expressive, angelic face to go along with the stuff that he had to do.

Dante: We knew he could carry a movie, and he’s nonthreatening. He was likable, and he was a good actor. And he related to not only the puppets, but he related to the dog.

Galligan: Susan Arnold pokes her head out the door and goes, “Zach, Phoebe.” And I was like, “Oh snap, we’re even paired together.” So we went in. And I think her being so calm, cool, and collected and sucking all the energy out of the room and making me a bit of an afterthought was a good thing, because it took all of the pressure off of me. Usually the spotlight’s on just you.

Finnell: We decided on Phoebe Cates almost immediately.

Galligan: They had to take the tape and they had to FedEx it to Spielberg. Apparently when Spielberg saw me put my head on her shoulder, he turned to Joe and he said, “Stop the tape. Just turn it off.” And they were like, “What?” Joe and Mike thought he wanted to discuss something. And he got up, started walking out. And they said, “What?”

Dante: Steven turned to me and said, “We’ve got to cast him. He’s already in love with her.”

Part 4: “An Ongoing Madness”

The movie was shot on backlots at Warner Bros. and Universal Studios. The way Dante saw it, an artificial environment was the only place where the Gremlins could feel alive.

Dante: They wanted to shoot it on real streets. And I said, “You can’t take these puppets out in the real street.” The idea was that the more stylized the movie was, the more the Gremlins would be acceptable. One of the fun things about it was doing the whole thing at Warner Bros. on the backlot.

Finnell: It was in Burbank, and it was just suburban streets, and they shot a lot of sitcoms and TV series there.

Dante: We took a lot from It’s a Wonderful Life, which we stole a lot of plot points [from] as well.

Galligan: Joe calls Gremlins “It’s a Wonderful Lizard of Oz in Hell.”

Dante: It was a movie movie. We were always aware that we were making a movie.

James Spencer (production designer): It transcends reality in a way. And so you buy into it almost immediately.

Galligan: I met Chris Columbus on the set. He was 23, and was basically a pretty fresh-faced kid from Chicago, just thrilled to have, really, his big break. And so he was just like I was on the set. We’re both looking at each other like, “How did we win the lottery?”

Cates: I just remember loving the largeness of it. And being on that backlot. And then how homespun it was, having guys on the floor with straws in their mouth, blowing air into the Gremlins. There was something really fun and behind-the-magic-curtain about it all.

John Louie (shop owner’s grandson): Joe was definitely infectious. He was always very disciplined in his approach, but childlike in his wonder.

Glynn Turman (Roy Hanson): He was a kid in the toy shop.

Cates: He is the greatest guy. And it was the most fun I’ve ever had on probably any movie.

Galligan: They had Phoebe and I come out about 10 or 12 days before shooting. Most of it was so I could do what I call Barney bonding, which was developing a real bond with Mushroom, the dog that played Barney in the movie. So they would drive me out to Warner Bros., to where Ray Berwick, the animal coordinator, was. And I would spend an hour with Mushroom, giving him treats, throwing balls, playing with him, petting him, giving him more treats. And it worked.

Dante: We had a great dog in the movie who thought the puppets were real. We got a lot of great stuff from this dog. I mean, he would just surprise us in these scenes. The dog and Corey Feldman were the actors who most related to the puppets as if they were actually alive.

Feldman: You can really see it in that scene with me and Gizmo on the bed. Obviously I know that there’s puppeteers behind the wall. There’s 10 guys laying on the floor with headsets on and air pumps in their mouth or air pumps in their hands or electronic remote controls in their hands. And I know that, but still I was able to look at it as like, “Well, let’s forget all that’s there and just look at Gizmo as if Gizmo was like my puppy.”

Louie: It was nice to see [Dante] approach my scenes, like, “This is pretty magical, this creature, but you’ve got to treat it very cavalierly. You’ve seen this all the time.”

Galligan: After I had done some Mushroom time, Mike Finnell was like, “Do you want to go see the creature shop?” And I was like, “Absolutely.” I hadn’t even seen a sketch of what anything looked like. So I walk into the creature shop and the first thing I see is just a table full of Gremlins. And they were just stacked next to each other and they formed these two long rows. And on all the tables were Gremlins and Mogwai in various states being built. They were nasty looking. They were more vicious looking than I had anticipated.

Louie: I seem to recall a time where I was like, “I’d like to go see what the evil Gremlin looks like.” And Joe was like, “Yeah, it’s right over there. Go take a look.” And as I tiptoed over there, my mom seems to remember that she saw a bunch of people scurrying behind me that I didn’t see. I walked up to an inanimate object, and then they made it move. I just ran. It was so great.

Walas: When we finally came to production, we had enough of the puppets together to do the scenes that were scheduled. There wasn’t a lot of ad-lib stuff going on at that point. I think that the most critical shot for me as the Gremlin creator and supervisor was the shot in the kitchen with Billy’s mom. I think it’s the first time you see a Gremlin. and he rises up, turns around, and he’s got a lot of his animatronic stuff going.

McCain: I wanted to kill the prop guy. He was throwing real plates at me in real-time. Yeah, it was crazy, and I was defending myself with a TV tray. But it was hilarious.

Walas: I’m shaking. All over if this is going to work or not. We shoot the first take and I’m going, “We can make this movie. I know we can make this movie now.”

Finnell: You had to shoot a lot of film and to find those few seconds where the Gremlins really looked alive, because Chris Walas would be on headsets and all the puppeteers would be underneath operating, and Joe would say, “OK, tell them, ‘Wiggle his ears.’” And then Chris would tell his puppeteers what to do. And so you would have this thing flailing, and then all of a sudden, everything would come together for a couple of seconds and look real, like they’re alive. In fact, when Steven first saw the movie, Tina Hirsch, our editor, was in the screening, and he turned to her and he said, “Boy, you had quite a job.”

Walas: Things shifted and grew. There was the whole thing of “Well, we can have Gizmo drive a toy car.” And I’m like, “Wait, we can? How do we do it?” And then I’m like, “We’ll figure this out.” The prop guy’s there the next morning with three Barbie Corvettes. It was an ongoing madness for myself and my crew.

Dante: The Gremlins would break. And that meant we were idling, like, 50 to 70 people who are on the job all the time underneath the floor of the set, doing animatronics with little TV screens so they could see what they were doing with the image reversed—because we’re all used to looking at ourselves in the mirror. And in order to make one Gremlin do one thing, sometimes it took as many as five, six, seven people.

Galligan: Even when it was take 17 or take 19, I think the best thing that happened was that Joe Dante expected that. He wasn’t yelling and screaming, he wasn’t panicking, he just very much had a, like, “It is what it is” type of thing. And then Gizmo would break. When the dog stepped on Gizmo’s ear and tore the ear off in the Christmas gift scene, we had a 7-hour break. And I loved it because I just went over to Spielberg’s office and played his stand-up video games that he had in his office. He wasn’t there, he was shooting Temple of Doom. But he had a Millipede machine. And I played and got incredibly good at it.

Walas: It was difficult for me, but it was wonderful being on these shots where we had Billy’s friend. He’s shooting the slingshot out his window, and initially there were no Gremlins in the shot, and so Joe was like, “Well, can we just get one up here in the tree?” And I think the scene winds up with another four or five puppets.

Dante: He did an amazing job with what he had and the time that he had, which was not enough.

Walas: I just woke up one morning and had a surprise, and that was a kidney stone, which is a very painful experience. I didn’t even know what a kidney stone was, at that point. So that was pretty debilitating.

Finnell: He was under tremendous pressure.

Walas: And then I broke my ankle, and that was actually on the same shot on the rooftop with the slingshot, and we were working out of a trailer that was on the stage, and we had a set of wooden stairs there. Well, I had a cold at the time, and I was on cold medication, and just completely exhausted and a little woozy, and I missed a step. So that was off to the medical center. It was a rough show for me.

Dante: I just remember one night that Chris Walas and I and the DP are working on a Gremlin shot that took forever. Later that night, we came back and they had ordered pizza for the crew and all the pizza was eaten and we didn’t get any. I said, “That sums up our whole experience on this.”

Part 5: “Perverse in the Way That People Love”

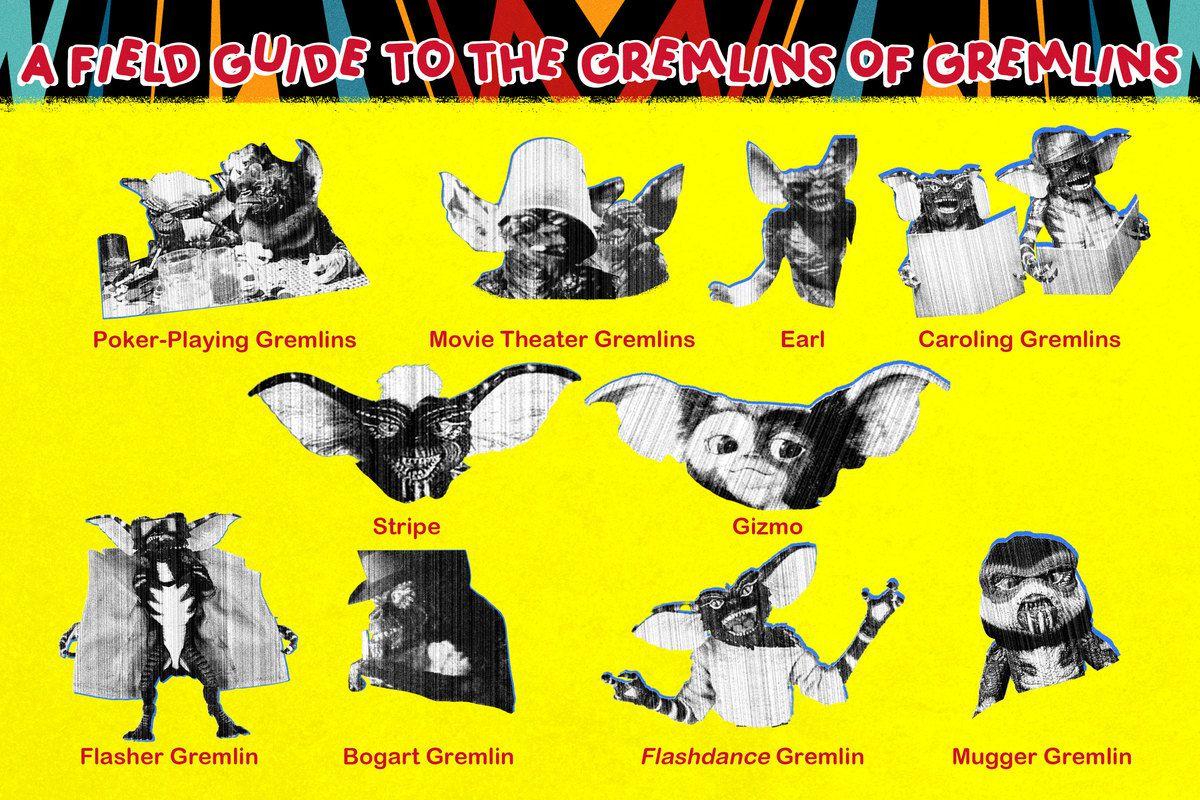

Walas and his crew eventually got the hang of bringing the Gremlins to life. The process never stopped being exhausting, but as shooting moved along, it got more and more fun. The movie is chock-full of set pieces that seesaw between funny and scary. There are scenes in a pool, a bar, a movie theater, a department store, and the house of a Scrooge-like woman who the Gremlins make sure has no redemption arc.

Walas: We started figuring out that these puppets could do a lot more than was in the script, and they could be a lot sillier. And then the light really went on when we were shooting the [Gremlin] carolers outside in the snow, because they’re all dressed up and suddenly they become these Warner Bros. cartoon characters that Joe always wanted in a movie. And from then on, all hell broke loose. It was just a mad, chaotic dash to get through the day.

Galligan: The Joe Dante moment in the movie for me is launching Mrs. Deagle out the window.

McCain: Only someone who really had that film sensibility—and could reference the Wicked Witch—would have been able to think of that.

Feldman: He’s got a look and an essence and a feel that is 100 percent uniquely Joe.

Walas: In the theater scene where we had the big shots of all the Gremlins [watching Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs] in one row, Joe just kind of goes, “You direct that. You direct that stuff.” I’m like, “Really?” He’s going, “Yeah. You could do it.” And he was great. We even got Joe down in the front, doing puppets.

Finnell: Luckily, all these studios wanted to stay on Steven’s good side. Kathy Kennedy knew a guy, an executive [at Disney] at the time, and called him up and said, “We really want to use this scene from Snow White for this movie.” And they talked him into it.

Walas: We were just having a blast at that point. And then there was the other time that Joe let me direct a shot, and that was the Flasher puppet. And that was fun because Joe just said, “Yeah, just go crazy,” and that’s what was basically the direction I handed to the puppeteers.

Dante: He’s in the sequel, too. He was very popular. In fact, there’s a toy.

Walas: Dorry’s Tavern was just insane. By this point I’m running on empty, and we’re only about halfway through the production, and Joe puts up this sheet on the wall, to the crew: “Anybody who comes up with a great idea for the Gremlins to do anything, just write stuff down and we’ll try and shoot everything.” And I’m like, “That’s going to kill us.”

Dante: There were so many Gremlins in that scene, and they were doing so many different things, and there were so many people that you had to hide that it just became logistically really difficult.

Walas: We had real beer, we had real peanuts, popcorn.

Dante: Well, after a couple of weeks of beer and popcorn, it really smelled bad. And poor Phoebe, she turned green in all of the garbage and having to do things over and over because the Gremlins didn’t work. I mean, that’s the other thing about the actors: They have to be very patient. It’s like working with animals.

Cates: I don’t think that part was particularly fun. I just remember being kind of physically exhausting. And there were a lot of moving parts, and thankfully, I wasn’t responsible for 90 percent of that.

Walas: I’ll never forget, we were setting up a shot, and I hear Phoebe scream, and I’m going, “Wow, that was really convincing!” And then she says, “There’s a huge fucking cockroach on the counter!” And there was. There were rats. It was a once in a lifetime experience, thankfully.

Spencer: Thinking back on it now, it’s Looney Tunes. At the end of every day, we all just laughed ourselves silly.

There’s a moment in the movie that, on the surface at least, is not so silly. Kate tells Billy a story about why she hates Christmas: When she was a kid, her missing father was found dead in her chimney. He’d dressed up as Santa Claus, climbed down on Christmas Eve, slipped, and broke his neck. “And that’s how I found out there was no Santa Claus,” Kate says. The moment of extreme comedic bleakness was, well, controversial.

Cates: It’s perverse in the way that people love.

Galligan: What she did, which is what all good comic actors do, was that she realized that to her character, it wasn’t funny. It was tragic. But it’s so ridiculous. It’s absurd.

Dante: Phoebe knew that that speech had not been written for her character, but was actually written in the earlier version of the movie for the owner of a McDonald’s that the Gremlins trash and they eat all the people, but not the McDonald’s. But I liked the speech. [Studio execs] said, “Let’s give her the idea that she doesn’t like Christmas. [But] you have to explain why.” And this speech was perfect, to explain why.

Cates: Joe was so great. He’s that kind of director who just steps in and gives you like, “Really love this, make sure to do that again. Let’s go again.”

Galligan: She thought it was going to be her big moment. And it is, because it’s 40 years later and we’re still talking about it. She knew that the rest of her part was pretty much attractive love interest, and that this was her really meaty scene and chance to really make a lasting impact. And to her credit, she was 100 percent correct.

Dante: I thought she was great in the scene, and I thought the scene was wonderful. When we were walking away from the dailies, the editor turned to me and said, “This will never be in the movie.” And I said, “I think it should be in the movie.” So it did become a point of contention. The first note was “Don’t cut a frame, except take out that speech.” And I said, “I think it’s important to the movie. And it encapsulates the whole ethos of what’s funny and what’s not funny.”

Fisher: My boss, Bob Daly, he was a pretty straight businessman, so he didn’t like Santa getting stuck in the chimney. He thought that it would frighten people, and he just didn’t like it. And we all liked it. But Joe loved it. It came to a boiling point. I remember a meeting with Joe and him. I was there. Joe practically started to cry, and he said, and he wasn’t kidding, “It’s the whole reason why I wanted to make the movie.”

Dante: They said, “Well, we’ll get Steven to make you cut it out.” So they went to Steven and said, “Make him cut it out.” And Steven said, “It’s his movie. I don’t even get it. I don’t know what it is he likes about it, but it’s his movie. Leave it in there.” So it stayed in the movie.

Finnell: At the end originally, when they go into the greenhouse in the department store and open the blinds and the sun comes in and melts Stripe, Billy did that. That was entirely Billy. And Steven said, “Well, Gizmo really needs to be the hero.” We just had to make a couple of changes, showing Gizmo grabbing the cord that opened the blinds. We added that, and then we finished the movie.

Galligan: The best line that Joe ever got off to me was when I watched it. When that happens, I did turn around to him and go like this, “Are you kidding me?” And he’s like, “Hang on, hang on.” And I waited. And afterwards I go, “How could you have Gizmo save the day?” And he looks at me and he goes, “The name of the picture is Gremlins, not Billy Peltzer’s Adventures in Kingston Falls.’” And I was like, “Wow. Twist the knife in while you’re at it.”

Part 6: “There’s Always a Twinkle in the Film”

Gremlins wasn’t quite finished. It still needed three things:

1. Voices for the Gremlins and Mogwai, especially the hero Gizmo.

2. A unique musical score that matched the movie’s unique tone.

3. The skeptical studio to finally come around to the genre-bending film.

Howie Mandel (voice of Gizmo): I got the movie when the movie was made. My buddy Frank Welker said to me, “I’m going to do voices on this. You should come in. You do great voice work.” And he brought me in for the audition. I imagined it was a little kid’s movie with animatronics. I had no idea what it was.

Dante: Howie had a character that he had already done that was sort of like a baby character. And so I had heard him do that voice. With that in mind, we thought, “Well, maybe this would be a good voice for this creature.” Because we’re working in the dark. We don’t know what these things should sound like.

Mandel: I came to that voice as a young kid choking on a piece of cake. If I could describe what goes into making that voice, it’s not a falsetto. That voice is if you took a balloon, and you blew up a balloon, and then you stretch the nipple of the balloon, and you push the air out. So even if I lose my voice, I can do that. That’s just air. So when I was choking, that’s the sound that came out.

Dante: It was obvious that this was the voice for this character.

Mandel: When I did Gizmo, it was just taking the same voice and not speaking English and being a little more garbled and emotional.

Dante: The good thing about puppets is you can keep changing the soundtrack after you’ve shot it because all they do is they just move their mouths.

Mandel: I sat with Joe every day, and we dubbed it and made sounds and did all these kinds of little Easter eggs. I just remember watching [the movie] and saying funny things under my breath. We were having so much fun—adult fun, comedy, scary fun. I thought up until that time it was really easy to target an audience. And I felt, “Who is this for? Isn’t this really scary for really little kids? Isn’t this really dark for a Christmas movie?” I don’t think, up until this time, I had been aware of a movie that checked such a wide plethora of boxes.

Galligan: I thought the tone of the movie was going to be a little bit more like Aliens. And if you changed the music, it might’ve been. If it was a bit more like Brad Fiedel’s Terminator score, then it might’ve felt that way. But instead you had Jerry Goldsmith’s very whimsical “Gremlin Rag.”

Finnell: Jerry had a studio in his house, where he would do a rough approximation on a little electric piano. Steven says, “Listen to this.” Jerry plays what became known as the “Gremlin Rag,” which is the, “Dun, dun, dun, dun, dun, dun.” And it was completely different from what, I guess, we all thought: a horror movie score. And it was this insane kind of demented carnival music. We realized, “This is actually perfect.” Because there’s an undercurrent of menace, yet it’s also funny.

Dante: We were not taken seriously by the studio. When they saw the rough cut, they didn’t get it. They thought the Gremlins were kind of gross. And they kept complaining to Steven. And they said how much they hated the Gremlins. And he said something like, “Well, we could cut out all the Gremlins and call it People, but I don’t think anybody’s going to go.”

Galligan: I thought it was going to be a big success when we did it, and actually I was in the minority. I think that Joe, and even to a certain extent, Steven and Mike Finnell, and even Warner Bros., thought they were making this quirky little horror movie. But my personal feeling was that they were making a fundamental mathematical error, which is that this was the next Spielberg movie with his name stamped on it that was coming out after Poltergeist and E.T., which was, at the time, the most successful movie that had ever been released.

Finnell: Normally, the studio would say, “Let’s just go out and preview it with a temp score and not finish the sound.” And Steven said, “No, this is going to rely on as much postproduction as possible to make these things look alive.” And so we went up to Sacramento with a version of the movie and ran it.

Dante: You’ve got to remember this movie came out of nowhere. Nobody knew anything about it. It had no big names in it.

Finnell: Joe and I are sitting next to each other, and actually George Lucas was there. Steven invited George. We’re sitting there going, “What are these people going to think?” We start to run it, and then the key moment was when Hoyt Axton gives Billy the box with Gizmo in it and it opens up, and Gizmo comes out, and the audience goes, “Aw.” We go, “Oh, thank God.” Because you’re thinking they’re going to laugh at this ridiculous thing, but they didn’t.

Dante: It was weird and crazy in a way that they didn’t expect.

Finnell: The real moment was the scene with the mother in the kitchen with the blender and the microwave. The audience went apeshit. I mean, they just went apeshit. And I turned to Joe and I said, “You know, I think maybe we have a hit here.”

Dante: The reaction was phenomenal. I mean, every director should have at least one preview that is this good.

Fisher: As soon as we started to show it to audiences, people really liked it.

Dante: The studio smelled money, and then all of a sudden they were like, “Oh, this is great. We’re going to sell the hell out of this.” They got behind it, they belatedly came up with a whole bunch of merchandising and stuffed animals.

Fisher: Until kind of Batman, Warners did not understand merchandising, really.

Dante: What I didn’t expect was that the advertising for the movie would make it look like the son of E.T., because obviously they didn’t want to give away the Gremlins. So the ad is a little fuzzy hand coming out of a box with the same colors as the ads for E.T. and Steven Spielberg’s name plastered all over the place. And I think it led a lot of parents to think, “Oh, this is just a cuddly, cute movie that I can bring my kids to.” And of course it was never intended to be that.

Finnell: It was rated PG.

Dante: Stuff like the [Gremlin exploding in the] microwave got us in big trouble. They decided it shouldn’t be a PG anymore.

Finnell: A lot of people thought that it should have been an R. I said, “Well, it’s not. Actually, what it should be is something in between.” Actually, because of Gremlins and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, which also had some kind of gnarly things in it, the PG-13 rating was invented.

Dante: Children are pretty smart. I never heard of anybody putting their chihuahua in a microwave.

It may take place at Christmas, but Gremlins hit multiplexes on June 8, 1984, the same day as Ghostbusters. (“It was always targeted as a summer movie,” Finnell says.) That weekend, Dante’s opus finished a close second to the supernatural comedy and ended up grossing $153.6 million domestically against its $11 million budget. The surprise hit made Dante and Galligan famous, spawned creature-feature knockoffs, and eventually led to a 1990 sequel that was so ludicrously inventive that it inspired a Key & Peele sketch about how it was made. The original—which got a 4K DVD release in 2019 and is now merchandised to the gills—is still anarchic comfort food. After all, there’s no Christmas tradition like gathering in front of your TV and watching a reptilian monster melt down to a bubbling puddle of goo.

Galligan: Phoebe and I, we were in L.A. for the premiere at Mann’s Chinese Theatre. And I wasn’t going to miss that, my God. And so Joe and Mike go, “Hey, do you want to come see the movie beforehand?” There’s this tiny screening room attached to some production office. And so Joe and Mike sat behind us, so we didn’t have to watch their expressions. They didn’t want us to take cues from them. And Phoebe and I sat there, and we watched it. And I have to tell you, when I saw the first cut with Phoebe and the music, I did not like it. And of course, it’s Joe. It’s cartoony.

[But] watching a film without an audience is a very wildly different experience from watching a movie with an audience. And Gremlins is one of the great examples of that, because the difference between watching that alone and watching that with 1,500 screaming people at the Mann’s Chinese Theatre was so profound. I’m doing a lot of running, and I’m blowing up movie theaters, and she and I are racing through stuff, I’m pulling up in cars and saving her from the bar, I’m hacking things off with swords. I’m doing all of this swashbuckling stuff. And then Jerry Goldsmith comes on and it’s like, “This is so silly and fun.”

Feldman: Let’s face it, it really covers all the bases. Not only is it a great family holiday film, but it’s a real horror movie. Not only does it feature some great scares and jumps and all that, it’s got the Spielberg magic with the cute, cuddly, strange creature.

Mandel: My jaw dropped to the fucking table. It was amazing. It was so much more than I thought it was. It was so surprisingly wonderful and thought out. And Joe, he’s like this brilliant conductor of an orchestra that can make each instrument take all these weird sounds and images and put them together and create a masterpiece. That’s what he did.

Dante: I watched a woman at a screening of Gremlins. She was dragging her child out of the theater during the microwave scene and the child was screaming, “I don’t want to go! I don’t want to go!” And that kid got away and ran back and hid in the theater. And so this woman is standing at the doorway with me watching the rest of this movie because she doesn’t know where her kid is. And I thought, this is a funny scene. So I reenacted it and put it into Gremlins 2.

Fisher: At one point I’m sitting next to somebody, and I hear the person mumbling and pissed off, and I kind of cock my ear and he goes, “Goddamn, that Steven Spielberg. I’ve had to go to the bathroom for an hour, and I can’t leave.” When somebody is saying, “I want to go to the bathroom and I can’t leave,” you had a hit.

Dante: When they offered me the sequel right away when the movie was a big hit, I said, “No, I can’t stand any more puppets. I don’t want to see any more puppets.”

Walas: I needed a break at the end of shooting. I needed a break halfway through shooting. I was anemic, and I was totally tapped out as a living creature. My wife and I went to Hawaii. I spent the first three days watching Sesame Street, and that’s all. It was on eight times a day, and I was just burned out.

But it was a once in a lifetime experience, without question. And it was a life changer for me because it was so overwhelming and imposing a project to go into with the limited experience I had at that time in my career. I was basically terrified from day one to the end of the show. But having gone through that, and having been successful at the job, I realized that if I can do Gremlins, I can pretty much do anything.

Galligan: It was a lot. I mean, literally June 1, I’m walking around Manhattan on the Upper West Side, where I was born and raised, and I’m basically unknown. And July 4, I walk into a restaurant on the Upper West Side, and when I walk in, the entire restaurant turns around, looks at me, and then starts whispering. Some people are giggling, some people are frowning. And as a 20-year-old, you’re going like, “Oh my God, are they laughing at me? What are they talking about me?” Now I’m 60. I don’t give a fuck. But when you’re 20, you care about what everybody thinks about you. Although I do know some 60-year-olds who still care about what everyone thinks about them.

Fisher: They were all newbies. Everybody was, and Joe had done a few Corman movies, so he wasn’t inexperienced, but he certainly hadn’t worked in the studio system much.

Dante: A couple years earlier, I’m working for Roger Corman making movies that I don’t think anybody’s seeing. And now all of a sudden I’m in Time magazine.

Galligan: After the movie was over, I come home from school, and my freight elevator back door of a second-floor apartment in Manhattan goes, “Ding!” And I open it, and there’s a big guy out there in a blue jumpsuit. He’s like, “You Zach Galligan? Sign right here, and here, and initial here.” And then he opened the door and it’s this giant box. And I open it in the kitchen, and it’s the Millipede machine. And it had a card in it saying, “Guess you like this more than I do. Steven.”

Cates: For me, it’s all about the experience of doing it. And anything after—it’s always been like that for me—nothing else really matters. But I can always tell when somebody comes up to me and they say, “My favorite movie …” I know which one it’s going to be.

Finnell: It’s part of the zeitgeist. I mean, “Don’t feed them after midnight …”? Everybody knows what that means.

McCain: There’s always a twinkle in the film in some way. And it’s because of that twinkle in Joe’s eye.

Fisher: I have one of the few stuffed-animal Gizmos that I’ve taken to every job I’ve had. Still sits on my couch very wide-eyed.

Dante: You’ve got to remember that these kinds of movies were generally considered lowbrow and that they were made because they used to make back their money in a couple of weeks and then they would disappear. Then years later they’d come on television. That was about it. That was the shelf life. But nobody imagined that this picture would still be running theatrically, which it is all over the country.

Galligan: I went to a premiere of a movie called Kalifornia. The stars of the movie at the time were Brad Pitt and Juliette Lewis, who were dating. I went to the after-party. I was outside in the backyard, it was a garden, and they were taking pictures of Brad and Juliette Lewis as they arrived. And he’s smiling, and he looks over at me for a second, and then he looks back, and then he looks over at me again. And I’ve never met him. And he’s squinting his eyes. And after the pictures, he’s like, “OK, thanks guys.” And the paparazzi start rewinding their cameras and writing things down, like paparazzi do. And he turns to Juliette Lewis, and he says something, which I imagine is, “Hang on a second, baby.”

And he walks over towards me and he goes, “Hey, man, how you doing?” And I said, “Good.” He goes, “I just want to tell you, prom night, Springfield, Missouri, 1984, I went to my prom, and then me and my girlfriend went out, saw Gremlins at a drive-in theater, we sat on the roof of my car, and it just made the whole experience for me, man. So you’re a big part of my growing up, and I just wanted to say that’s awesome.”

The idea that Brad Pitt saw Gremlins on his prom night is one of the greatest things ever.

Interviews have been edited and condensed. Through an Amblin representative, Steven Spielberg declined an interview request for this article. Chris Columbus couldn’t be reached for an interview.