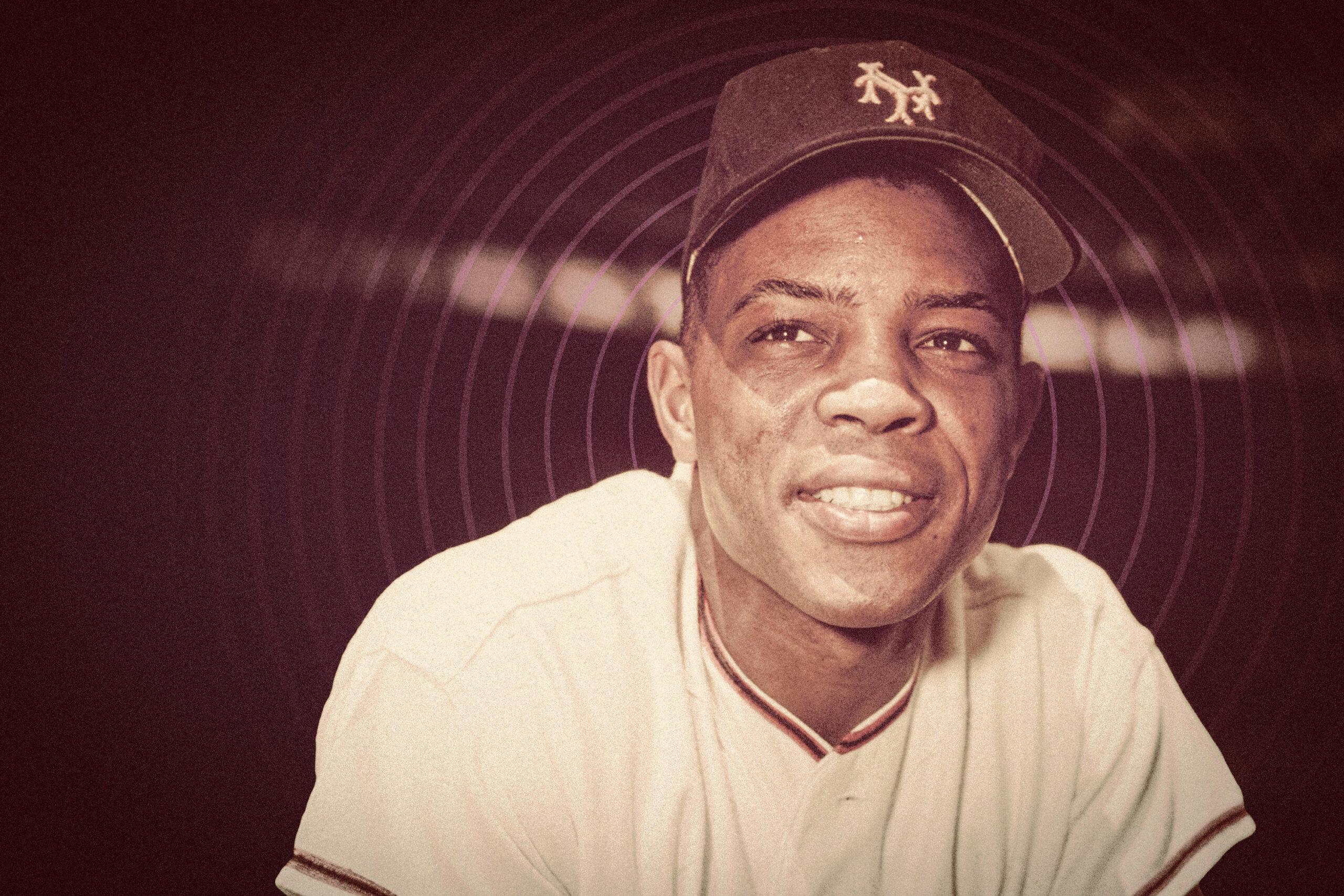

From the moment he retired—if we’re being honest, from a few years before that—and for the rest of his life, Willie Mays had a compelling case as the world’s Greatest Living Ballplayer.

Mays died Tuesday, after a life lived in full, 93 circuits around the sun. He was the last surviving member of the iconic superstar class that defined baseball’s self-proclaimed Golden Age. Mickey Mantle, Stan Musial, Ted Williams, Frank Robinson, Henry Aaron—inner-circle Hall of Famers whose careers overlapped in the late 1950s—all passed away before him. Mays’s death closes the chapter on an entire era of baseball history and rips open a void in the sport that will take time to heal.

It’s not simply that Mays was the last of those superstars, though. It’s that he was the best of them. He was considered an all-time great throughout his career, and yet he was underrated. He played with a singular flair that influenced the game for generations to come, and yet his legacy goes so far beyond that. He was transcendent in virtually every respect: culturally, historically, statistically, stylistically.

Mays wasn’t simply the Greatest Living Ballplayer. He was one of a handful of men who can stake a serious claim as the Greatest Ballplayer Who Ever Lived. And he might have the best claim of them all.

Wins above replacement is not the be-all and end-all of baseball statistics. It is simply a tool, a useful framework to sum up the contributions a player makes on the field as a way to facilitate comparisons. Now that we have issued that disclaimer, here are the players who have accumulated the most WAR in baseball history, according to Baseball Reference:

- Babe Ruth (182.6)

- Walter Johnson (166.9)

- Cy Young (163.6)

- Barry Bonds (162.8)

- Willie Mays (156.2)

- Ty Cobb (151.5)

- Henry Aaron (143.1)

- Roger Clemens (139.2)

- Tris Speaker (134.9)

- Honus Wagner (131.0)

We can quibble over the order, but as a list of the players with the most impressive statistical résumés in major league history, this certainly passes the eye test. Look at the list for another moment, however, and a few other things stand out. Six of the 10 men above played before Jackie Robinson broke MLB’s color barrier in 1947. (These men also did not face a slider, or play a game at night, but let’s stay focused.) Two of the other four men are Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens. I am not here to tell you that allegations of performance-enhancing drug use should disqualify them from being considered as Greatest Ballplayer Who Ever Lived. I am not sure that I believe that myself. But I would argue that, in terms of forcing a critical reevaluation of their legacies, we should focus on settling the debate about their Hall of Fame inclusion before making the case for them as the GOAT.

That leaves Willie Mays and Henry Aaron.

The next-best player whose entire career took place after integration was Alex Rodriguez (117.6), who … yeah. After A-Rod, it’s Rickey Henderson (111.1). Rickey was a tremendous ballplayer, the all-time record holder in runs scored and stolen bases, but the gap between him and Mays is 45 WAR, or the statistical equivalent of Buster Posey’s entire career. Again, WAR isn’t everything—but I’m not sure there are enough intangibles in the world to make up a 45-win gap. Particularly when the player 45 wins ahead is Willie Mays, who oozed intangibles from every pore.

So it’s Mays and Aaron, Aaron and Mays, same as it ever was. Contemporaries born three years apart, both debuted in the National League at age 20 and played until they were 42. Aaron passed Babe Ruth as the career home run record holder, and he still holds the all-time records for RBIs and total bases (6,856, 645 more than any other player in history). He was a paragon of consistency, a metronome of productivity, an All-Star in 21 consecutive seasons. At the plate he was every bit Mays’s equal, to the point that their career slash lines are almost indistinguishable:

- Willie Mays: .301 AVG, .384 OBP, .557 SLG, 155 OPS+

- Hank Aaron: .305 AVG, .374 OBP, .555 SLG, 155 OPS+

But that sort of gives away the game. Aaron may have been Mays’s equal at the plate, but just his equal. And when it came to all the things a player does on the field outside the batter’s box, Mays had no equal whatsoever.

Mays hit 660 home runs in his career, but he didn’t have a bat in his hands for the signature moment of his career—arguably the signature moment in baseball history. The Catch, his game-saving robbery of Vic Wertz in the 1954 World Series opener, was a microcosm of Mays as a player: His contribution was delivered with such obvious and staggering greatness that it obscured even more value under the surface. Everyone remembers the Catch, particularly since Mays made a basket catch out of the play. But few remember the throw immediately following it, a heads-up play by Mays that prevented Larry Doby—who was tagging at second base—from advancing two bases and scoring the go-ahead run. (Mays, remember, was more than 450 feet from the plate when he caught the ball.) Doby held at third base and was left stranded, and the Giants won 5-2 in extra innings. They would sweep Cleveland—winner of a then–American League record 111 games in the regular season—and earn Mays his one championship ring. The award for World Series MVP was renamed in Mays’s honor in 2017.

What elevates Mays above even other inner-circle Hall of Famers is that, for his entire career, he provided value in more ways than anybody else. There was his bat, every bit the equal of Aaron’s or Frank Robinson’s. There was his glove, which modern analytics say was as good as his reputation and his 12 Gold Gloves suggest, if not better. Mays’s defense alone was worth 185 runs over an average center fielder during his career. And there was his baserunning, another part of his repertoire that was partly obscured by the era in which he played. He led the NL in stolen bases in four straight years from 1956 to 1959 without ever stealing more than 40 in a season. He took the extra base on base hits as well as anyone in the game, going first-to-third or second-to-home on singles (or first-to-home on doubles) at a remarkable 63 percent clip in his career. (Henderson took the extra base only 55 percent of the time in his career.) Mays is credited with 79 runs above average on the bases, more than Vince Coleman (75) even though Coleman had 752 career steals to Willie’s 339.

And then there is Mays’s most important hidden ability of all: durability. From 1954 through 1966, Mays played in at least 151 games every year. The NL was still playing a 154-game schedule for the first seven years of that stretch; he didn’t miss more than five games in any season until 1966, when he missed nine. Playing a half-dozen extra games in a season does not provide a ton of value—but do that for 13 straight years and the value adds up, particularly when you play as well as Mays did. Avoiding injuries also allowed Mays to age extraordinarily well, particularly in terms of speed and defense. Other generational defenders in center field, like Ken Griffey Jr. and Andruw Jones, saw their defensive value fall off a cliff by the time they turned 30. But Mays rated as a plus-18 defender in 1966, at age 35. He was one of the best base runners in the league at age 39, when he took the extra base on hits 74 percent of the time, and at 40, when he stole 23 bases and led the NL with an 88 percent success rate. He was ageless and he was peerless. From 1954 to 1966, he led the NL in bWAR 10 times in 13 seasons. He didn’t win 11 MVP awards, because award voting doesn’t work like that. But he certainly could have.

Of all the incredible things about Mays’s career, the fact that he played just as well and as often at age 34 as he did at age 23 may be the hardest to replicate. Consider the plight of one of the few players who at any point could have also honestly been considered for the title of Greatest Living Ballplayer: Mike Trout, who led the AL in bWAR five straight years from ages 20 to 24, and who went into his age-28 season—merely five years ago!—with 72.5 bWAR, 22 wins ahead of Mays’s pace. Five years later, Trout has added just 14 wins to his total. He’s now 11 wins behind Mays, and about to enter his age-33 and age-34 seasons, when Mays registered back-to-back 11-win seasons. (There have been just five 11-win seasons by a position player in the 58 seasons since.)

How best to quantify the breadth of Mays’s talents? If you were to adjust his statistical record to make him a league-average hitter for his entire career—stripping him of 804 runs above average—he would be worth around 72 bWAR. Derek Jeter finished his career with 71.3 bWAR. If Mays were just a tremendous defensive center fielder and elite base runner who played for over 20 years but was average at the plate, he’d still be a Hall of Famer. The real thing was two Hall of Famers in one.

For a player whose style and flair transcended the numbers, it is telling that the analytics movement burnished his reputation decades after he retired. As a child in the 1980s, I can tell you that while Mays was regarded as an iconic superstar, he wasn’t necessarily regarded in a different light than Mickey Mantle or Joe DiMaggio among retired center fielders. After all, Mantle and DiMaggio’s raw offensive statistics—which were the only stats we had at that point—were slightly better. But as analytics developed, we better understood the stats we had: that Mays’s numbers were suppressed by his ballpark for much of his career, and significantly suppressed by the expanded strike zone that allowed pitchers to dominate the sport from 1963 to 1968. And we developed new statistics to quantify his defensive and baserunning contributions, which turned out to be even greater than many had suspected. Some players rack up traditional numbers, and some players are hidden analytical darlings. Mays, it turned out, was both.

And the most ridiculous thing is that his statistical record could have been even better, should have been even better, through no fault of his own.

In one sense, Willie Mays arrived at precisely the right time, just as Black men took the field in the National League and American League. It is a minor miracle that he emerged when he did, when segregation in baseball was in its death throes even if the powers that be didn’t give it up without a fight. Had Mays been born even five years earlier, a significant portion of his career in the NL would have been truncated. As it is, his major league record was recently updated to account for the 13 games he played in the Negro American League as a 17-year-old with the Birmingham Black Barons in 1948.

Missing from that earlier list of the top 10 players of all time, per bWAR? Satchel Paige, who debuted in the AL at age 42 and was an All-Star at age 46 despite pitching for the St. Louis Browns; Josh Gibson, who, as of last month, is recognized by MLB as the career record holder in batting average (.372) and slugging percentage (.718), supplanting Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth; and Oscar Charleston, whom Bill James ranked as the fourth-greatest player of all time in his New Historical Baseball Abstract. It is by a quirk of time that essentially Mays’s entire career took place in integrated leagues, with the clear statistical records of every game to go with them, allowing everyone to know with complete clarity exactly how good he was.

But while Mays’s statistics weren’t significantly altered by segregation, they were significantly altered by war. His career was impacted by the Korean War, specifically, and just as the Korean War feels like the forgotten war in our cultural zeitgeist, Mays’s absence for the better part of two seasons (he was called into the service in May 1952 and didn’t return until 1954), feels overlooked in the narrative of his career. This is ironic since war is definitely part of the narrative for Ted Williams, the only other star player who missed time to the Korean War. Granted, Williams had already missed three years to World War II, and he was flying a fighter jet and being John Glenn’s wingman, and he was shot down and almost died. Plus, Williams was an established superstar when he went into the service, whereas Mays wasn’t quite yet. But Mays had won Rookie of the Year honors in 1951, and more to the point, he won the NL MVP in his first year back from the service. And Mays actually missed slightly more time than Williams did. (Mays played 34 games in 1952, Williams played six games in 1952 but returned in time to play 37 games in 1953.)

Given Mays’s track record of durability—he had started every Giants game from the time of his major league debut until he was called away—it seems safe to assume that he would have played the majority of the 274 games that he missed. How much value he would have provided is hard to say; he left as an up-and-coming star and returned as the greatest player in the game. But we can estimate with some simple math. In 155 career games before Korea, Mays was worth 5.5 bWAR. When he returned in 1954, he was worth 10.5 bWAR in 151 games. Average the two numbers, and Mays would have been worth about eight wins per full season during the time he was in the service. Over the 274 games he missed, that comes out to about 14 bWAR—nearly 10 percent of his career total. Credit Mays with another 14 wins, and he doubles the distance between him and Aaron on the list, takes the post-integration lead over Barry Bonds, and moves up to second place all-time behind only Babe Ruth.

Mind you, no one benefits from this type of accounting for statistics lost to war service more than Williams, who by this method lost around 46 wins above replacement. Credit Williams with those numbers, and he goes from having 122 bWAR—outside the top 10—to around 168, in third place behind only Ruth and Mays. But Williams played five of his 19 seasons before integration (and if we account for his WWII years, it would be eight of 22), and the AL was much slower to integrate than the NL, contributing to a significant talent disparity between the leagues that persisted through the late 1960s. (In 1965, 15 Black future Hall of Famers played in the major leagues. All 15 played in the NL.) The quality of competition that Williams and Mickey Mantle—for so long Mays’s contemporary as a center fielder for a New York team—faced was significantly weaker than what Mays faced.

But the statistical impact of Mays missing almost two full seasons to the war isn’t limited to some theoretical accounting invented more than half a century later. His absence deprived him of a chance to break the most hallowed record in sports. Mays hit 24 home runs in 1951 and 1952, and 41 in 1954. Do the same math averaging that we did with wins above replacement, and we can estimate that Mays would have hit approximately 58 home runs in the time he spent in the service. Mays retired 54 home runs short of Babe Ruth’s career mark of 714.

Willie Mays was called to serve his country, and he answered the call. But had he played in a different era—or had his draft number simply been different—it might have been him and not Aaron who broke the all-time record. He had the talent to be baseball’s all-time home run king. He simply lacked the opportunity.

If there is an argument to be made that Mays is not the Greatest Ballplayer Who Ever Lived, it comes down to comparing eras. All available evidence indicates that the quality of baseball played in the majors has inexorably improved, almost without interruption, from 1876 through today. Judging simply by the average fastball velocity measurements over the last 15 years, that trend shows no signs of slowing down. By this line of logic, the Greatest Ballplayer Who Ever Lived must always be an active or recently retired player. Putting Barry Bonds aside for a moment—and how absurd is it that the most credible contender for Mays’s title could be his own godson?—that would mean the GOAT was at one point Albert Pujols, and then Trout, and now it’s probably Mookie Betts. In 10 years we may look back and say it was Gunnar Henderson or Bobby Witt Jr. And there’s no way to know how Mays would have adapted to the major leagues had he come up in the 21st century, facing 95 mph fastballs every night, pitches cooked up in a lab, and three or four different pitchers in a game. There’s no way to know how he would’ve handled all the ways the game has changed and become more challenging in the 50 years since he retired.

But there’s also no way to know how the modern major leagues would have adapted to him. We don’t know how good Mays would have been had he gotten to face the best players in the country his age, growing up competing at showcase events. We don’t know how much better he might have been had he not grown up in the Jim Crow South, had he not had to deal with the specter of racism his entire career, had he not had to fight against redlining even as a superstar living in San Francisco. We will never know how Willie Mays would have fared had he been born in our time because he was born in his time. And the impact he made during his time will live on forever.

What we do know is that no one who played against the best baseball players in the world ever dominated them as much as Mays did, for as long as Mays did, with as much style as Mays did. He was a giant of the game. He was the GOAT before we called them GOATs. He was the Greatest Ballplayer Who Ever Lived.